Fish Sammich with Cheese

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BET Networks Delivers More African Americans Each Week Than Any Other Cable Network

BET Networks Delivers More African Americans Each Week Than Any Other Cable Network BET.com is a Multi-Platform Mega Star, Setting Trends Worldwide with over 6 Billion Multi-Screen Fan Impressions BET Networks Announces More Hours of Original Programming Than Ever Before Centric, the First Network Designed for Black Women, is One of the Fastest Growing Ad - Supported Cable Networks among Women NEW YORK--(BUSINESS WIRE)-- BET Networks announced its upcoming programming schedule for BET and Centric at its annual Upfront presentation. BET Networks' 2015 slate features more original programming hours than ever before in the history of the network, anchored by high quality scripted and reality shows, star studded tentpoles and original movies that reflect and celebrate the lives of African American adults. BET Networks is not just the #1 network for African Americans, it's an experience across every screen, delivering more African Americans each week than any other cable network. African American viewers continue to seek BET first and it consistently ranks as a top 20 network among total audiences. "Black consumers experience BET Networks differently than any other network because of our 35 years of history, tremendous experience and insights. We continue to give our viewers what they want - high quality content that respects, reflects and elevates them." said Debra Lee, Chairman and CEO, BET Networks. "With more hours of original programming than ever before, our new shows coupled with our returning hits like "Being Mary Jane" and "Nellyville" make our original slate stronger than ever." "Our brand has always been a trailblazer with our content trending, influencing and leading the culture. -

Artemis 2020 Artemis Design and Layout Is Based on Sacred Geometry Proportions of Phi, 1.618

Artemis 2020 Artemis design and layout is based on Sacred Geometry proportions of Phi, 1.618. This number is considered to be the fundamental building block of nature, recurring throughout art, architecture, botany, astronomy, biology and music. Named by the Greeks as the Golden Mean, this number was also referred to as the Divine Proportion. The primary font used in Artemis is from the Berkeley family, modernized version of a classic Goudy old-style font, originally designed for the University of California Press at Berkeley in the late 1930s. Rotis san Serif is also used as an accent font. Featured Cover Artist: Dorothy Gillespie Featured Image Cover: Festival: Sierra Sunset, 1988 Back Cover: New River: Celebration, 1997 Featured Writer: Natasha Trethewey Featured Poem: Reach Editor-in-chief: Jeri Rogers Literary Editor: Maurice Ferguson Art Editor: Page Turner Associate Editor: Donnie Secreast HINGE SCORE HINGE Design Editor: Zephren Turner Social Media Editor: Crystal Founds Board Legal Advisor: Jonathan Rogers Publishing Advisor: Warren Lapine Community Liason Editor: Julia Fallon Blue Star Implosion Gwen Cates Artemis Journal 2020, Volume XXVII 978-1-5154-4492-3 (Soft Cover) 978-1-5154-4493-0 (Hard Cover) Copyright 2020 by Artemis Journal All rights reserved. This book or any portion thereof may not be reproduced or used in any manner whatsoever without the express written permission of the publisher except for the use of brief quotations in a book review. Printed in United States of America by Bison Printers Artemis/Artists & Writers, Inc. P.O. Box 505, Floyd, Va. 24091 www.artemisjounal.org I 100 years ago, women gained the right to vote in the United States by the passage of the 19th amendment. -

Sunday Morning Grid 5/1/16 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 5/1/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Boss Paid Program PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Rescue Red Bull Signature Series (Taped) Å Hockey: Blues at Stars 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) NBA Basketball First Round: Teams TBA. (N) Basketball 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Woodlands Amazing Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday Midday Prerace NASCAR Racing Sprint Cup Series: GEICO 500. (N) 13 MyNet Paid Program A History of Violence (R) 18 KSCI Paid Hormones Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local 24 KVCR Landscapes Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Martha Pépin Baking Simply Ming 28 KCET Wunderkind 1001 Nights Bug Bites Space Edisons Biz Kid$ Celtic Thunder Legacy (TVG) Å Soulful Symphony 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto Paid Program Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División: Toluca vs Azul República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Schuller In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Formula One Racing Russian Grand Prix. -

Mick Evans Song List 1

MICK EVANS SONG LIST 1. 1927 If I could 2. 3 Doors Down Kryptonite Here Without You 3. 4 Non Blondes What’s Going On 4. Abba Dancing Queen 5. AC/DC Shook Me All Night Long Highway to Hell 6. Adel Find Another You 7. Allan Jackson Little Bitty Remember When 8. America Horse with No Name Sister Golden Hair 9. Australian Crawl Boys Light Up Reckless Oh No Not You Again 10. Angels She Keeps No Secrets from You MICK EVANS SONG LIST Am I Ever Gonna See Your Face Again 11. Avicii Hey Brother 12. Barenaked Ladies It’s All Been Done 13. Beatles Saw Her Standing There Hey Jude 14. Ben Harper Steam My Kisses 15. Bernard Fanning Song Bird 16. Billy Idol Rebel Yell 17. Billy Joel Piano Man 18. Blink 182 Small Things 19. Bob Dylan How Does It Feel 20. Bon Jovi Living on a Prayer Wanted Dead or Alive Always Bead of Roses Blaze of Glory Saturday Night MICK EVANS SONG LIST 21. Bruce Springsteen Dancing in the dark I’m on Fire My Home town The River Streets of Philadelphia 22. Bryan Adams Summer of 69 Heaven Run to You Cuts Like A Knife When You’re Gone 23. Bush Glycerine 24. Carly Simon Your So Vein 25. Cheap Trick The Flame 26. Choir Boys Run to Paradise 27. Cold Chisel Bow River Khe Sanh When the War is Over My Baby Flame Trees MICK EVANS SONG LIST 28. Cold Play Yellow 29. Collective Soul The World I know 30. Concrete Blonde Joey 31. -

2020 Frankfurt Rights Guide

2020 FRANKFURT RIGHTS GUIDE Dutton Penguin Plume TarcherPerigee Sabila Khan Director, UK & Translation Rights Phone: 212-366-2798 [email protected] Jillian Fata Associate Manager Phone: 212-366-2449 [email protected] Penguin Publishing Group, 1745 Broadway, New York, NY 10019 0 TABLE OF CONTENTS Fiction……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..1 History, Psychology, Science, Sociology…………………………………………………………………………………………………..5 Creativity, Gift, Humor, Pop Culture………………………………………………………………………………………………………..8 Memoir………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….12 Business, Parenting, Self-Help, Spirituality…………………………………………………………………………………………….12 1 FICTION Chamberlain, Lauryn FRIENDS FROM HOME Fiction | Dutton Hardcover | June 2021 | UK & Translation Rights Agent: Allison Hunter @ Janklow & Nesbit | Editor: Cassidy Sachs Status: manuscript available Jules and Michelle have been best friends since third grade, but now in their mid-twenties, they live miles—and worlds—apart. When Jules agrees to be the maid of honor in Michelle’s wedding, she quickly realizes just how different the two have become, which is only underlined when Jules decides to have an abortion, a decision that Michelle vehemently and ideologically opposes. With their friendship reaching a breaking point, is the bond they once shared as girls strong enough to reunite the women they’ve become? Lauryn Chamberlain studied journalism and French at Northwestern University and then moved to New York City, where she worked for several years as a journalist, freelance writer, and contact strategist. Choi, Eun-young SHOKO’S SMILE Literary Fiction | Penguin Trade Paperback | June 2021 | UK Rights Agent: Barbara Zitwer @ The Barbara J. Zitwer Agency | Editor: Margaux Weisman Status: manuscript available In crisp, unembellished prose, Eun-young Choi paints intimate portraits of the lives on young women in South Korea, balancing the personal with the political. -

First Dance & Standards Song Artist All My Love the Beatles at Last Etta

First Dance & Standards Song Artist All my love The Beatles At Last Etta James Better Together Jack Johnson Best Thing Ray Lamontagne Can you feel the love Tonight Elton John Come Fly with Me Frank Sinatra Crazy Patsy Cline Crazy Love Van Morrison Dream a little dream of me Michael Buble Eternal Flame The Bangles Fly me to the Moon Frank Sinatra Grow Old With You Adam Sandler Have I told you Latley Rod Stewart Home Edward Sharpe and the Magnetic Zeros Home Michael Buble I can't Help Falling in love with you Elvis Presley I got you Babe Sonny & Cher I hope You Dance Lee Ann Womack I just called to say I love You Stevie Wonder If I aint got You Alicia Keyes I'm Yours Jason Maraz In My Life Beatles Into the Mystic Van Morrison Is this Love Bob Marley Isn't She Lovely Stevie Wonder It Had to be you Harry Conick Jr Just the Way You Are Billy Joel Lucky Colbie Caillie & Jason Maraz Make you feel my love Adelle No Woman/No Cry Bob Marley Save the last Dance for Me The Drifters Sparks Cold Play Summer Wind Frank Sinatra Thank You Led Zepplin The Way You Look Tonight Frank Sinatra They Cant take that away from me Frank Sinatra True Colors Cyndi Lauper Unforgettable Nat King Cole What a Wonderful World Louis Armstrong When I'm 64 The Beatles Wonderful Tonight Eric Clapton You and Me Dave Mattews Your Song Elton John Me and You Kenny Chesney Moondance Van Morrison More Today Than Yesterday Spiral Staircase Ohh Baby Baby Linda Ronstadt Someone Like You Van Morrison Somewhere over the rainbow Israel Kamakawiwo'ole Son of A Preacher Man Dusty Springfield -

Cleveland, TN 24 PAGES • 50¢ Inside Today Watson Defends Deleting Posts He Said Some Used ‘Disturbing’ and ‘Inappropriate’ Language

W E D N E S D A Y 161st YEAR • NO. 292 APRIl 6, 2016 ClEVElAND, TN 24 PAGES • 50¢ Inside Today Watson defends deleting posts He said some used ‘disturbing’ and ‘inappropriate’ language By BRIAN GRAVES Tuesday stating the organization duties as sheriff,” wrote Amanda Banner Staff Writer “received several complaints Knief, national legal and public about the BCSO banning com- “After we posted the story from policy director for American Sunday’s Banner, the response was over- Sheriff Eric Watson has come menters and deleting reviews and Atheists, Inc. in Washington, D.C. whelming, with hundreds of replies just under fire again for posts on the posts on its official Facebook It is the same organization within the first day. But on Monday, there Bradley County Sheriff’s Office page.” which complained to Watson last social networking page. was a disturbing amount of what bor- “These comments and posts week over postings and articles dered on the pornographic from those The criticism is for what was were supportive of the atheist which express a view of faiths. who claimed to be critics of my stand.” posted and later taken down. The point of view and critical of either The letter said it was evident — Sheriff Eric Watson sheriff is not backing down. the sheriff’s office or of your advo- “by the activity witnessed on April The American Atheists Legal cating for your own religious Center sent an email to Watson beliefs while performing your See WATSON, Page 2 Bears get the sweep TDOT 9 WVHS The Bradley Central Bears pulled off the two-game sweep of baseball the Cleveland Blue Raiders in funds for baseball. -

Today's TV Programming Aces on Bridge Decodaquote® Celebrity

8A » Wednesday,May 25, 2016 » KITSAPSUN Today’s TV programming MOVIES NEW 5/25/16 11:00 11:30 NOON 12:30 1:00 1:30 2:00 2:30 3:00 3:30 4:00 4:30 5:00 5:30 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 [KBTC] Sesame Tiger Curious Curious Dino Super Cat in Peg Clifford Nature Wild Wild Ready Odd NHK Asia Antiques Antiques Masterpiece Masterpiece Mystery! [KOMO] KOMO 4News The Chew (TVPG) General Hospital The Doctors Steve Harvey KOMO 4News News ABC KOMO 4News Wheel J’pardy! Movie: Finding Nemo (2003) ‘G’ Nashville (TVPG) News [KING] New Day NW KING 5News Days of our Lives Dr. Phil (TV14) Ellen DeGeneres KING 5News at 4KING 5News at 5 News News News Evening Heartbeat (TV14) Law &Order: SVU Chicago P.D. News [KONG] Beauty Copper J. Meyer GT News New Day NW Meredith Vieira The Dr. Oz Show Rachael Ray Extra Celeb Inside Holly Dr. Phil (TV14) KING 5News at 9 News Dr Oz [KIRO] Young &Restless KIRO News The Talk (TV14) FABLife (TVPG) Bold Minute Judge Judge News News News CBS Insider ET The Price Is Right Criminal Minds Criminal Minds News [KCTS] Dino Dino Super Thomas Sesame Cat in Curious Curious Rick Steves Europe Marathon News Busi PBS NewsHour SciTech Field Nature (TVPG) Genius-Stephen Genius-Stephen Yoga [KMYQ] Divorce Divorce Judge Judge Judge Mathis Cops Cops Crime Watch TMZ Dish Mother Mother Two Two Simpson Simpson Mod Mod Q13 News at 9Theory Theory Friends [KSTW] Patern Patern Hot Hot Bill Cunningham People’s Court People’s Court Fam Fam Seinfeld Seinfeld Fam Fam Mike Broke Arrow (TV14) Supernatural Broke Mike Family [KBCB] -

Music List by Year

Song Title Artist Dance Step Year Approved 1,000 Lights Javier Colon Beach Shag/Swing 2012 10,000 Hours Dan + Shay & Justin Bieber Foxtrot Boxstep 2019 10,000 Hours Dan and Shay with Justin Bieber Fox Trot 2020 100% Real Love Crystal Waters Cha Cha 1994 2 Legit 2 Quit MC Hammer Cha Cha /Foxtrot 1992 50 Ways to Say Goodbye Train Background 2012 7 Years Luke Graham Refreshments 2016 80's Mercedes Maren Morris Foxtrot Boxstep 2017 A Holly Jolly Christmas Alan Jackson Shag/Swing 2005 A Public Affair Jessica Simpson Cha Cha/Foxtrot 2006 A Sky Full of Stars Coldplay Foxtrot 2015 A Thousand Miles Vanessa Carlton Slow Foxtrot/Cha Cha 2002 A Year Without Rain Selena Gomez Swing/Shag 2011 Aaron’s Party Aaron Carter Slow Foxtrot 2000 Ace In The Hole George Strait Line Dance 1994 Achy Breaky Heart Billy Ray Cyrus Foxtrot/Line Dance 1992 Ain’t Never Gonna Give You Up Paula Abdul Cha Cha 1996 Alibis Tracy Lawrence Waltz 1995 Alien Clones Brothers Band Cha Cha 2008 All 4 Love Color Me Badd Foxtrot/Cha Cha 1991 All About Soul Billy Joel Foxtrot/Cha Cha 1993 All for Love Byran Adams/Rod Stewart/Sting Slow/Listening 1993 All For One High School Musical 2 Cha Cha/Foxtrot 2007 All For You Sister Hazel Foxtrot 1991 All I Know Drake and Josh Listening 2008 All I Want Toad the Wet Sprocket Cha Cha /Foxtrot 1992 All I Want (Country) Tim McGraw Shag/Swing Line Dance 1995 All I Want For Christmas Mariah Carey Fast Swing 2010 All I Want for Christmas is You Mariah Carey Shag/Swing 2005 All I Want for Christmas is You Justin Bieber/Mariah Carey Beach Shag/Swing 2012 -

PLANNER PROJECT 2016... the 90S!

1 PLANNER PROJECT 2016... THE 90s! EDITOR’S NOTE: Listed below are the venues, performers, media, events, and specialty items including automobiles (when possible), highlighting the years 1991 and 1996 in Planner Project 2016! 1991! 1991 / FEATURED AREA MUSICAL VENUES FROM 1991 / (31) Agora Theatre (Cleveland) (25 years) / Around the Corner / Babylon A Go-Go / Biggie’s Crooked River Saloon / Blossom Music Center / Brothers Lounge / Cheers Outback Tavern / City Blues / CSU Convocation Center (1st metal concert) / Cuyahoga Falls High School / Derby & Flask / The Empire on E. 9th / Euclid Tavern / Front Row Theater / Lake County’s Summerfest ’91 / Nautica Stage in the Flats / Music Hall / Oriole Café / Palace Theatre / Peabody’s DownUnder / Phantasy Theater in Lakewood / Public Hall / 19th Annual Rib Burn Off on Mall C / Richfield Coliseum / Richie’s River Tavern (formerly D’Poo’s) / Rick’s Cafe / Riverwood Tavern / Rockin’ Richie’s on Detroit / Sahara Club / Splash / State Theatre / The Symposium / Tri-C Metro Auditorium / Tri-C JazzFest / Wing Ding at the Berea Fairgrounds 1991 / FEATURED ARTISTS / MUSICAL GROUPS PERFORMING HERE IN 1991 / [(-) NO. OF TIMES LISTED] FEATURED NORTHEAST OHIO / REGIONAL ARTISTS FROM 1991 / [Individuals: (55) / Groups: (48)] 13 Engines / 14th Floor / American Front / Armstrong-Bearcat (w/Alan Greene) / Atomic Punks / Beatnik Termites / Bluto’s Revenge / Miles Boozer / Becky Boyd & Dan Hrdlicka / Bop Kats reunite / Calabash with Bob Gatewood / Carton Freeze Tag / the Clarks / Cleveland Interfaith Choir / Cleveland -

SEPTEMBER 6, 2021 Delmarracing.Com

21DLM002_SummerProgramCover_ Trim_4.125x8.625__Bleed_4.375x8.875 HOME OF THE 2021 BREEDERS’ CUP JULY 16 - SEPTEMBER 6, 2021 DelMarRacing.com 21DLM002_Summer Program Cover.indd 1 6/10/21 2:00 PM DEL MAR THOROUGHBRED CLUB Racing 31 Days • July 16 - September 6, 2021 Day 15 • Thursday August 12, 2021 First Post 2:00 p.m. These are the moments that make history. Where the Turf Meets the Surf Keeneland sales graduates have won Del Mar racetrack opened its doors (and its betting six editions of the Pacific Classic over windows) on July 3, 1937. Since then it’s become West the last decade. Coast racing’s summer destination where avid fans and newcomers to the sport enjoy the beauty and excitement of Thoroughbred racing in a gorgeous seaside setting. CHANGES AND RESULTS Courtesy of Equibase Del Mar Changes, live odds, results and race replays at your ngertips. Dmtc.com/app for iPhone or Android or visit dmtc.com NOTICE TO CUSTOMERS Federal law requires that customers for certain transactions be identi ed by name, address, government-issued identi cation and other relevant information. Therefore, customers may be asked to provide information and identi cation to comply with the law. www.msb.gov PROGRAM ERRORS Every effort is made to avoid mistakes in the of cial program, but Del Mar Thoroughbred Club assumes no liability to anyone for Beholder errors that may occur. 2016 Pacific CHECK YOUR TICKET AND MONIES BEFORE Classic S. (G1) CONFIRMING WAGER. MANAGEMENT ASSUMES NO RESPONSIBLITY FOR TRANSACTIONS NOT COMPLETED WHEN WAGERING CLOSES. POST TIMES Post times for today’s on-track and imported races appear on the following page. -

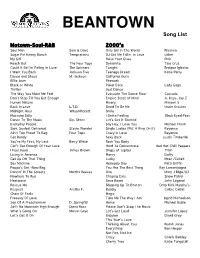

Beantown Song List 2010

BEANTOWN Song List Motown-Soul-R&B 2000’s Soul Man Sam & Dave Only Girl In The World Rhianna Sugar Pie Honey Bunch Temptations DJ Got Me Fallin in Love Usher My Girl Raise Your Glass Pink Reach Out The Four Tops Dynamite Taio Cruz Could It Be I’m Falling In Love The Spinners Tonight Enrique Iglesias I Want You Back Jackson Five Teenage Dream Katie Perry Dance and Shout M. Jackson California Gurls Billie Jean FIrework Black or White Poker Face Lady Gaga Thriller Just Dance The Way You Make Me Feel Evacuate The Dance Floor Cascada Don’t Stop Till You Get Enough Empire State of Mind A. Keys, Jay Z Human Nature Misery Maroon 5 Back In Love L.T.D. Good To Be Me Uncle Kracker Midnight Hour WilsonPickett Smile Mustang Sally I Gotta Feeling Black Eyed Peas Dance To The Music Sly. Stone Let’s Get It Started Everyday People Say Hey, I Love You Michael Franti Sign, Sealed, Delivered Stevie Wonder Single Ladies (Put A Ring On It) Beyonce Ain’t Too Proud To Beg Four Tops Crazy In Love Beyonce Get Ready Sexy Back Justin Timberlak You’re My First, My Last Barry White Rock You Body Can’t Get Enough Of Your Love Hard To Concentrate Red Hot Chilli Peppers I Feel Good James Brown Drops of Jupiter Train Living In America Mercy Duffy Get Up Off That Thing Lucky Mraz /Collait Sex Machine Heavenly Day Patti Griffin Poppa’s Got -New Bag You Are The Best Thing Ray Lamontaigne Dancin’ In The Streets Martha Reeves One Mary J Blige/U2 Nowhere To Run Chasing Cars Snow Patrol Heatwave Save Room John Legend Rescue Me Shipping Up To Boston Drop Kick Murphy’s Respect Aretha F.