Compilation of Papers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Malaysia Real Estate Highlights

RESEARCH REAL ESTATE HIGHLIGHTS 1ST HALF 2016 KUALA LUMPUR PENANG JOHOR BAHRU KOTA KINABALU HIGHLIGHTS KUALA LUMPUR HIGH END CONDOMINIUM MARKET The residential market continues to remain lacklustre with lower volume and value of transactions recorded. ECONOMIC AND MARKET INDICATORS Limited project completions and new Malaysia’s economy expanded at a launches of high end condominiums / slower pace in 2015 with Gross Domestic residences during the review period. Product (GDP) growing at an annual rate of 5.0% (2014: 6.0%). For 2016, the Government has trimmed the country’s Growing pressure on rentals amid GDP growth forecast to 4 - 4.5% due to strong supply pipeline (existing and the volatility in crude oil prices and other new completions) and a challenging economic challenges. GDP continued rental market while prices in to moderate in the first quarter of 2016, the secondary market generally posting 4.2% growth, its slowest since continue to remain resilient. 3Q2009 (4Q2015: 4.5%), driven by domestic demand. Private consumption expanded by 5.3% while private Developers adopt innovative ‘push investment moderated to 2.2%. marketing’ strategies to boost Headline inflation for April 2016 registered at sales of selected projects and 2.1%. It is expected to be lower at 2% to 3% improve revenue. this year, compared to an earlier projection Aria of 2.5% to 3.5% and will continue to remain stable in 2017. (432 units) and The Residences at The Meanwhile, labour market conditions St. Regis Kuala Lumpur (160 units). continued to weaken with more retrenchment of workers, particularly in By the second half of 2016, the scheduled the manufacturing, mining and services completions of another five projects will sectors. -

Malaysia Real Estate Highlights

RESEARCH REAL ESTATE HIGHLIGHTS 2ND HALF 2016 KUALA LUMPUR PENANG JOHOR BAHRU KOTA KINABALU HIGHLIGHTS KUALA LUMPUR HIGH END CONDOMINIUM MARKET Despite the subdued market, there were noticeably more ECONOMIC INDICATORS launches and previews in the TABLE 1 second half of 2016. Malaysia’s Gross Domestic Product Completion of High End (GDP) grew 4.3% in 3Q2016 from 4.0% Condominiums / Residences in in 2Q2016, underpinned by private 2H2016 The secondary market, however, expenditure and private consumption. continues to see lower volume Exports, however, fell 1.3% in 3Q2016 of transactions due to the weak compared to a 1.0% growth in 2Q2016. economy and stringent bank KL Trillion lending guidelines. Amid growing uncertainties in the Jalan Tun Razak external environment, a weak domestic KL City market and continued volatility in the 368 Units The rental market in locations Ringgit, the central bank has maintained with high supply pipeline and a the country’s growth forecast for 2016 at weak leasing market undergoes 4.0% - 4.5% (2015: 5.0%). correction as owners and Le Nouvel investors compete for the same Headline inflation moderated to 1.3% in Jalan Ampang 3Q2016 (2Q2016: 1.9%). pool of tenants. KL City 195 Units Unemployment rate continues to hold steady at 3.5% since July 2016 (2015: The review period continues to 3.1%) despite weak labour market see more developers introducing conditions. Setia Sky creative marketing strategies and Residences - innovative financing packages Bank Negara Malaysia (BNM) lowered the Divina Tower as they look to meet their sales Overnight Policy Rate (OPR) by 25 basis Jalan Raja Muda KL City target and clear unsold stock. -

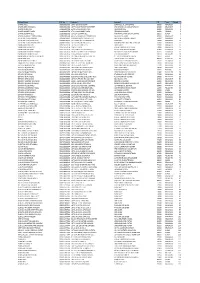

Business Name Business Category Outlet Address State 2020 Motor

Business Name Business Category Outlet Address State 2020 Motor Automotive TB 12186 LOT A 13 TAMAN MEGAH JAYA,JALAN APASTAWAU Sabah 616 Auto Parts Co Automotive Kian yap Industrial lot 113 lorong durians 112 Lorong Durian 5 88450 Kota Kinabalu Sabah Malaysia Sabah 88 Bikers Automotive D-G-5, Ground Floor, Block D, Komersial 88/288 Marketplace, Ph.10A, Jalan Pintas, Kepayan RidgeSabah Sabah Alpha Motor Trading Automotive Alpha Motor Trading Jalan Sapi Nangoh Sabah Malaysia Sabah anna car rental Automotive Sandakan Airport Sabah Apollo service centre Automotive Kudat Sabah Malaysia Sabah AQIQ ENTERPRISE Automotive Lorong Cyber Perdana 3 Penampang Sabah Malaysia 89500 Sabah ar rizqi Automotive Beaufort, Sabah, Malaysia Sabah Armada KK Automobile Sdn Bhd Automotive Ground Floor, Lot No.46, Block E, Asia City, Phase 1B Sabah arsy hany car rental Automotive rumah murah peringkat 1 no 54 Pekan Beaufort Sabah Atlanz Tyres Automotive Kampung Keliangau, Kota Kinabalu, Sabah, Malaysia Sabah Autocycle Motor Sdn Bhd Automotive lot 39, grd polytechnic, 8, Jalan Politeknik, Tuaran, Sabah, Malaysia Sabah Autohaven Superstore Automotive kg sin san peti surat 588 Kudat Sabah Malaysia Sabah Automotive Electrical Tec Automotive No 3, Block H, Hakka Building, Mile 5,5, Tuaran Road, Inanam, Kota Kinabalu, Sabah, Malaysia Sabah Azmi Sparepart Automotive Papar Sabah Malaysia Sabah Bad Monkey Garage Automotive Kg Landong Ayang Jln Landong Ayang 2 Kg Landong Ayang Jalan Landong Ayang II Kudat Sabah Malaysia Sabah BANLEE MOTOR Automotive BANLEE MOTORBATU 1 JLN MERINTAMAN98850 -

Property Market Review 2018 / 2019 Contents

PROPERTY MARKET REVIEW 2018 / 2019 CONTENTS Foreword Property Northern 02 04 Market 07 Region Snapshot Central Southern East Coast 31 Region 57 Region 75 Region East Malaysia The Year Glossary 99 Region 115 Ahead 117 This publication is prepared by Rahim & Co Research for information only. It highlights only selected projects as examples in order to provide a general overview of property market trends. Whilst reasonable care has been exercised in preparing this document, it is subject to change without notice. Interested parties should not rely on the statements or representations made in this document but must satisfy themselves through their own investigation or otherwise as to the accuracy. This publication may not be reproduced in any form or in any manner, in part or as a whole, without writen permission from the publisher, Rahim & Co Research. The publisher accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or to any party for reliance on the contents of this publication. 2 FOREWORD by Tan Sri Dato’ (Dr) Abdul Rahim Abdul Rahman 2018 has been an eventful year for all Malaysians, as Speed Rail) project. This move was lauded by the World witnessed by Pakatan Harapan’s historical win in the 14th Bank, who is expecting Malaysia’s economy to expand at General Election. The word “Hope”, or in the parlance of 4.7% in 2019 and 4.6% in 2020 – a slower growth rate in the younger generation – “#Hope”, could well just be the the short term as a trade-off for greater stability ahead, theme to aptly define and summarize the current year and as the nation addresses its public sector debt and source possibly the year ahead. -

Wtw Property Market 2009

C H Williams Talhar & Wong WTW PROPERTY MARKET 2009 KDN PP9013/07/2009(021839) Established in 1960, C H Williams Talhar & Wong (WTW) is a leading real estate services g company in Malaysia and Brunei (headquartered in Kuala Lumpur) operating with 25 n branches and associated offices. WTW provides Valuation & Advisory Services, Agency o & Transactional Services and Management Services. W & HISTORY r a Colin Harold Williams established C H Williams & Co in Kuala Lumpur in 1960. In 1973, h l the sole ownership became a 3-way equal partnership of Messrs C H Williams Talhar & a Wong following the merger with Johor based Talhar & Co (founded by Mohd Talhar Abdul T Rahman) and the inclusion of Wong Choon Kee. s m PRESENT MANAGEMENT a i l l The current Management is headed by the Group Chairman, Mohd Talhar Abdul Rahman. i The Managing Directors of the WTW Group operations are : W • C H Williams Talhar & Wong Sdn Bhd Goh Tian Sui • C H Williams Talhar & Wong (Sabah) Sdn Bhd Chong Choon Kim H • C H Williams Talhar Wong & Yeo Sdn Bhd (operating in Sarawak) Wong Ing Siong C • WTW Bovis Sdn Bhd Dinesh Nambiar Chairman’s Foreword In the wake of the Asian Financial Meltdown, our 1999 PMR stated that “the [property] market hurled into [an] abyss. It would have happened without the currency turmoil”. The collapse of the property market in Malaysia at the time was in the main due to the sheer excess of building activities, to overproduction of property units. Values plummeted then. They have not generally come back to where they were before in 1995/6. -

Pavillion Kuala Lumpur,Low Yat Plaza,Fahrenheit 88,Berjaya Times Square Kuala Lumpur,Kota Kinabalu,Klang Valley

Pavillion Kuala Lumpur At the heart of the trendy Bukit Bintang district lies the perfect reason to indulge in fashion, food and urban leisure. Experience the excitement of this 1.37 mil sq ft retail haven with over 500 outlets offering the finest fashion and home furnishing to entertainment and culinary delights. Let the endless appeal of Malaysia’s premier shopping destination awaken your senses the moment you arrive at its doorstep. Witness the Pavilion Crystal Fountain, a new national landmark. It is the Tallest Liuli Crystal Fountain in Malaysia endorsed by The Malaysia Book of Records. Another first in Malaysia is Pavilion KL’s seven distinguished shopping precincts and a row of street-front duplexes housing flagship boutiques from the world over. Address: 168, Jalan Bukit Bintang, Bukit Bintang, 55100 Kuala Lumpur Tel: (6) 03-2118 8833 Price Level: Expensive Website: http://www.pavilion-kl.com Low Yat Plaza Plaza Low Yat has all the intensity in digital hardware and software, as well as the present-day digital lifestyle diversity to validate this distinction. So much so, that the saying about Plaza Low Yat goes a little something like this: “If you can’t find the IT product you’re after at Plaza Low Yat, it probably doesn’t exist!” Dining, fashion, beauty and etc also available here at Plaza Low Yat which seven themed floors of top-name fashion boutiques, dining options galore, cutting-edge beauty & wellness centers and more, including quick break spots like Starbucks and Coffee Bean, Wi-Fi enabled of course! And all at The Plaza! Address: No. -

Lot CPI 22, Contact Pier International 2 Oldtown White Coffee (Genting Highlands) B5, Taxi Stand Resort Hotel, 3 Oldtown White Coffee (Kuching Airport) Lot No

No Name Address 1 OldTown White Coffee (KLIA) Lot CPI 22, Contact Pier International 2 OldTown White Coffee (Genting Highlands) B5, Taxi Stand Resort Hotel, 3 OldTown White Coffee (Kuching Airport) Lot No. L1L13, Public Concourse, Arrival Level, 4 OldTown White Coffee (KKIA) Lot No. L1L05, Level 1, Arrival Landside (Terminal 1, ETB), 5 OldTown White Coffee (Labuan Airport) Lot No. T1L1 MTB 2, Arrival Level, 6 OldTown White Coffee (CIMB, KLIA) Lot No. MTDB S4, Departure Level, Main Terminal Building, 7 OldTown White Coffee (Langkawi Airport) Lot Fh02 Food Hall Level 1 Departure Hall (Landside) 8 OldTown White Coffee (Gateway, KLIA2) Unit L3-27, 28 & 29, Level 3 (Departure Level), Gateway@KLIA2, 9 OldTown White Coffee (Arrival Area, KLIA2) Lot No. S2-2-1C05, Arrival Level, Public Concourse, 10 OldTown White Coffee (Subang Parade) Lot LGC17, Lower Ground Floor, Subang Parade Shopping Centre, 11 OldTown White Coffee (IPC Damansara) Lot No. L2 16, Level 2, IPC Shopping Centre, 12 OldTown White Coffee (Langkawi) Zone 3, Lot 8 & 9, 13 OldTown White Coffee (Kota Kemuning) No.8 Jalan Anggerik Vanilla S31/S, 14 OldTown White Coffee (Bandar Kinrara) No.1-0 & 3-0, Jalan BK 5A/3A, 15 OldTown White Coffee (Central Market) Lot.3.01 & 3.07, 1st Floor, 16 OldTown White Coffee (Giant Plentong) Lot No.R134, Giant Hypermart Plentong, 17 OldTown White Coffee (Syopz Taylors) Lot LG 2-2 & LG 2-3, Syopz Taylors Lakeside Campus, 18 OldTown White Coffee (Ipoh) Lot 37499, Jalan Dato Lau Pak Kuan, 19 OldTown White Coffee (Taman Permata, KL) No.1, Persiaran Permata, -

SIE2014 Handbook.Pdf

CONTENTS Page 1 Information on SIE2014 Page Form 3 Terms and Conditions/Rules and Regulations 18 Letter Of Indemnity 4 Exhibits Move-In Instructions 19 Form 1 of 7 31 July 2014 Exhibitor Information 4 Exhibits Move-Out Instructions 20 Form 2 of 7 31 July 2014 Advertisements (Exhibitors Directory Booklet) 4 Temporary Staff/Personnel 21 Form 3 of 7 31 July 2014 Shell Scheme Booth 5 Best Booth Competition 22 Form 4 of 7 15 August 2014 Heavy / Large Exhibits & Additional 5 Security and Insurance Furniture 6 Booth Requirements 26 Form 5 of 7 15 August 2014 Combined Commercial Invoice & Packing List 8 Information on Exhibition Site 27 Form 6 of 7 18 August 2014 Non-Ofcial Contractors 9 Promotion/Publication Requirements 29 Form 7 of 7 15 August 2014 Transportation 10 Other Item Available On Hire/On-Loan 11 Travel & Immigration Information 12 Immigration - Quarantine 13 Shipping and Forwarding Services INFORMATION ON SIE2014 1. Programme of SIE2014 DATE TIME PROGRAMME VENUE 16 - 17 SEPT, 8.00am-11.00pm Commencement work by External Contractors Grand Ballroom, Tues-Wed The Sutera Harbour Convention Centre, The Magellan Sutera, Sutera 17 SEPT, Wed 8.00am-11.00pm Move-In by Exhibitors Harbour Resort (Exhibition Site) 7:00pm-10.00pm WELCOME DINNER RECEPTION HOSTED BY THE STATE GOVERNMENT OF SABAH Grand Ballroom, The Pacic Sutera, Sutera Harbour Resort 18 SEPT, Thurs 10.00am-2.30pm OFFICIAL OPENING OF THE SABAH INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS LUNCHEON TALK 2014 (SIBC-LT 2014) Grand Ballroom, The Pacic Sutera, BY THE RIGHT HONOURABLE DATUK SERI PANGLIMA MUSA -

Final RMCD 6 Aug 2015

Outlets Name GST No# Address1 Address2 ZIP Town ShopNr CHANEL-KLCC 000836681728 LOT C G06-07 G FLOOR SURIA KLCC KL CITY CENTRE 50088 KUALA LUMPUR 2 CHANEL ONE UTAMA S.C. 000836681728 LOT F328 1ST FLOOR HIGHSTREET ONE UTAMA S.C. BANDAR UTAMA 47800 SELANGOR 3 CHANEL SURIA KLCC 000836681728 GO7B G FLOOR SURIA KLCC JALAN AMPANG 50450 KUALA LUMPUR 4 CHANEL GURNEY PLAZA 000836681728 170-G-10A GURNEY PLAZA PERSIARAN GURNEY 10250 PENANG 5 CHANEL KOMTAR JBCC 000836681728 LOT G27 KOMTAR JBCC MENARA KOMTAR JB CITY CENTRE 80000 JOHOR 6 CHANEL SUNWAY PYRAMID MALL 000836681728 G1.62 G FL SUNWAY PYRAMID S.M. NO.3 JLN PJS 11/15 46150 SELANGOR 7 LOUIS VUITTON (STARHILL) 001383915520 G19/23/29/30/37 INDULGE FLR 181 JLN B.B STARHILL GALLERY 55100 KUALA LUMPUR 8 LOUIS VUITTON (SURIA KLCC) 000984748032 LOT G26A-C & G27 GROUND FLR SURIA KLCC 50088 KUALA LUMPUR 10 LOUIS VUITTON (GARDENS MALL) 000984748032 LOT G239A,B & 240 GR FLR GARDENS MALL MV, LING.SY PUTRA 59200 KUALA LUMPUR 11 SWAROVSKI PAVILION 001676763136 LOT NO.3.47.00 LEVEL 3 PAVILION KL 55100 KUALA LUMPUR 13 SWAROVSKI SURIA KLCC 001676763136 106 1ST FLOOR KUALA LUMPUR CITY CENTER 50088 KUALA LUMPUR 15 SWAROVSKI 1 UTAMA 001676763136 LOT F348 1ST FLR 1 UTAMA S.C. NO.1 LEBUH BANDAR UTAMA 47800 SELANGOR 16 SWAROVSKI SUNWAY PYRAMID 001676763136 NO.LG1.56 LOWER G 1 S.PYRAMID NO.3 JLN PJS 11/15 BDR SUNWAY 46150 SELANGOR 17 SWAROVSKI GURNEY PLAZA 001676763136 170-G-20 PLAZA GURNEY PERSIARAN GURNEY 10250 PULAU PINANG 18 SWAROVSKI AEON IPOH STATION 18 001676763136 LOT G18 AEON IPOH STATION 18 S.C. -

Final Rmcd Consolidated File

TOURIST REFUND SCHEME (MALAYSIA) OUTLET NAME GST NUMBER OUTLET ADDRESS 1 Address 2 ZIP CODE STATE OUTLET REF NO. CHANEL - KLCC 000836681728 Lot C, G06-07 Ground Floor Suria KLCC, Kuala Lumpur City Centre 50088 Kuala Lumpur 2 CHANEL, One Utama Shopping Centre 000836681728 Lot F328, First Floor Highstreet, One Utama Shopping Centre,Bandar Utama 47800 Selangor 3 CHANEL Espace Parfum, Suria KLCC 000836681728 G07B, Ground Floor,Suria KLCC, Jalan Ampang 50450 Kuala Lumpur 4 CHANEL, Gurney Plaza 000836681728 170-G-10A, Gurney Plaza, Persiaran Gurney 10250 Penang 5 CHANEL, Komtar JBCC 000836681728 Lot G27, Komtar JBCC, Menara Komtar (Kompleks Tun Abdul Razak), Johor Bahru City Centre 80000 Johor 6 CHANEL, Sunway Pyramid Shopping Mall 000836681728 G1.62 Ground Floor, Sunway Pyramid Shopping Mall, No.3 Jalan PJS 11/15 46150 Selangor 7 CHRISTIAN DIOR - STARHILL 000042934272 G28, INDULGE FLOOR, STARHILL GALLERY, 181 JALAN BUKIT BINTANG 55100 Kuala Lumpur 65 Coach at KLCC 001228283904 Lot G01A-G01C Ground Floor, Kuala Lumpur City Center 50088 Kuala Lumpur 67 Coach at The Gardens 001228283904 Lot G223 Ground Floor, The Gardens Mid Valley City 59200 Kuala Lumpur 68 Coach at Pavilion 001228283904 Lots 3.12 & 4.12 Levels 3 & 4, Pavilion Kuala Lumpur Shopping Mall, 168 Jalan Bukit Bintang 55100 Kuala Lumpur 69 Coach at One Utama 001228283904 Lot GK2 Ground Floor, Centre Concourse 1 Utama Shopping Center, Bandar Utama 47800 Selangor 70 Coach at Gurney Plaza 001228283904 Unit 170 G-35/36 Ground Floor, Plaza Gurney 10250 Penang 71 Coach at First Avenue 001228283904 -

GSAA 201 Pembangunan Pendidikan Akan Tetap - Menjadi Agenda Utama Kumpulan Yayasan Sabah Demi Meningkatkan Kualiti Kehidupan Rakyat Malaysia Di Sabah

,, E VA BUT GSAA 201 Pembangunan pendidikan akan tetap - menjadi agenda utama Kumpulan Yayasan Sabah demi meningkatkan kualiti kehidupan rakyat Malaysia di Sabah. Dalam hal ini, pelbagai aktiviti pendidikan telah dilaksanakan oleh Kumpulan Yayasan Sabah. Pada tahun ini, sempena dengan bulan Ramadan yang mulia, Kumpulan Yayasan Sabah telah menganjurkan Majlis Berbuka Puosa Ketua Menteri Sabah Bersama Mahasiswa-Mahasiswi Sabah di Semenanjung Malaysia bertempat di Datuk Sapawi (enam, kiri) bersama antara barisan pengurusan atasan yang menghadiri majlis. Pusat Dagangan Dunia Putra, Kuala Tambah beliau lagi, Kerajaan Negeri dan dilaksanakan bagi memastikan Kumpulan Lumpur pada 27 Jun 2016. Persekutuan sentiosa mengambil berat Yayasan Sabah terus relevan . kepentingan belia di Sabah. Sebagai bukti Dalam ucapan beliau, Datuk Seri "Pada masa yang soma, Kumpulan komitmen itu, Kerajaan Negeri Musa berkata, "Pelbagai program Yayasan Sabah sentiosa peka dengan memperuntukkan RM90 juta menerusi yang melibatkan belia khususnya perkembangan dan situasi terkini serta Bajet Negeri Sabah 2016 bagi mahasiswa-mahasiswi sedang giat bergerak seiring dengan era transformasi memperkasa program pembangunan diatur oleh kerajaan agar anak-anak bagi memastikan Kumpulan Yayasan belia . sekalian tidak akan terpinggir dalam Sabah terus membantu merealisasikan orus pembangunan negeri dan "Ini sejajar dengan usoho melahirkan hasrot kerojaan," jelas beliau. negara." modal insan yang cemerlang, "Kumpulan Yayasan Sabah mensasarkan berkemahiran tinggi dan mampu memacu ,. Terang beliau lagi, "Biarpun berdepan generasi muda dalam mencapai matlamat pembangunan negeri dalam pelbagai dengan pelbagai caboran namun transformasi itu," katanya. Bagi memenuhi sektor," jelas beliau. komi akan tetap meneruskan usaha matlamat itu Datuk Sapawi berkata murni agar dapat mendekoti Datuk Seri Musa turut menekankon kepoda Kumpulan Yayosan Sabah okan terus golongon mudo sekolian. -

List of Atm As at December 2019

LIST OF ATM AS AT DECEMBER 2019 NO STATE LOCATION ADDRESS 1 FEDERAL TERRITORY AEON AU 2 Setiawangsa ATM 1 AEON AU2 Setiawangsa Shopping Centre (G17), 6 Jalan Taman Setiawangsa (Jalan 37/56), AU2 Bandar Baru Ampang, Mukim Ulu Kelang, 54200 Kuala Lumpur. 2 FEDERAL TERRITORY AEON AU 2 Setiawangsa ATM 2 AEON AU2 Setiawangsa Shopping Centre (G72), 6 Jalan Taman Setiawangsa (Jalan 37/56), AU2 Bandar Baru Ampang, Mukim Ulu Kelang, 54200 Kuala Lumpur. 3 FEDERAL TERRITORY AEON BIG Kepong ATM 1 Carrefour Shopping Centre Kepong, No 2 Jalan Metro Perdana, Taman Usahawan Kepong 52100 Kuala Lumpur. 4 FEDERAL TERRITORY AEON BIG Wangsa Maju ATM 1 No.6, Jalan 8/27A, Wangsa Maju, 53300 Kuala Lumpur. 5 FEDERAL TERRITORY AEON BIG Wangsa Maju ATM 2 No.6, Jalan 8/27A, Wangsa Maju, 53300 Kuala Lumpur. 6 FEDERAL TERRITORY Akademi Etiqa Bangunan Dato Zainal Akademi Etiqa, Bangunan Dato Zainal, 23 Jalan Melaka, 50100 Kuala ATM 1 Lumpur. 7 FEDERAL TERRITORY Alam Damai ATM 1 Alam Damai Branch, No 15 Jalan DP 5/1 B, Bandar Damai Perdana 56000 Cheras, Kuala Lumpur. 8 FEDERAL TERRITORY Alam Damai ATM 4 Alam Damai Branch, No 15 Jalan DP 5/1 B, Bandar Damai Perdana 56000 Cheras, Kuala Lumpur. 9 FEDERAL TERRITORY Alpha Angle ATM 1 Ground Floor, Alpha Angle Shopping Centre, Section 2, Bandar Baru Wangsa Maju, 53300 Kuala Lumpur. 10 FEDERAL TERRITORY APIIT University ATM 1 Asia Pacific Institute of Info Tech (APIIT), Technlogy Park Malaysia, 57000 Kuala Lumpur. 11 FEDERAL TERRITORY Bandar Sri Permaisuri ATM 1 Bandar Sri Permaisuri Branch, No 59 Ground, 1st & 2nd Floor, Jalan Sri Permaisuri 8, Bandar Sri Permaisuri, 56000 Kuala Lumpur.