Distant Affinities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

S Pirit T Ravel & T Ours

S S PIRIT T RAVEL & T OURS T T PO Box 1159 BUNDOORA VIC 3083 Phone: 03 9467 5022 Email: [email protected] www.spirittours.com.au ABN 28072444234 Bus Accreditation No: AO007584 S PIRIT T RAVEL & T OURS Specialists in Group Travel to TASMANIA (Small and Large Groups) Spirit Travel & Tours has +20 Years of Experience in Group Travel We have been successfully organising and running group tours to Tasmania since 1994 Minimum Group Size 17 people to upwards of 40 people - No need to worry about getting 40+ people to fill a big bus in order to run your tour Extensive knowledge of Locations, Accommodation and Sightseeing Opportunities - Due to the years we have been organising group tours and the number of times we have experienced Tasmania our knowledge and expertise is second to none We have a long-standing relationship with McDermott’s Coaches who have top-class drivers with extensive local knowledge Our drivers job is to ensure you have the best holiday or day tour experience possible . Buses are available from 24-seater, 33/35-seater, 48-seater to 57-seater. We fit the bus to your size group. Great Value, Competitive Pricing - As a small family-run business working from our home office, we have minimum overheads saving you money. Most of our business is word of mouth, or procured by getting out and seeing clubs such as your own without the need for expensive advertising costs – we pass on these savings to you. We offer excellent Properties for our tour stays Wrest Point and Riverfront Motel (Hobart), Launceston Country Club (Resort/Villas), The Strahan Village, and East Coast Hotels We can also offer accommodation in budget motels, we price your trip according to your needs. -

Hutchins School Magazine, №114, December 1965

1846 THE THINS S L MA AZINE Number 114 December 1965 THE STAFF 1965 Back Row: K. Dexter, M. L. Orgill, J. F. Millington, T. R. Godlee, M. C. How, T. Maclurkin, G. M. Ayling, F. Chinn, C. 1. Wood, D. R. Proctor, R. Penwright. Middle Row: S. C. Cripps, J. H. Houghton, Miss S. Hutchins, Mrs M. E. Holton, Mrs H. R. Dobbie (Matron), Mrs M. Watson, Miss E. Burrows, Mrs A. H. Harvey, A. B. Carey, B. Griggs. Front Row: D. P. Turner (Bursar), E. Heyward, V. C. Oshorne, G. A. McKay, J. ·K. Kerr (Second Master), D. R. Lawrence (Headmaster), M. B. Eagle (Chaplain), F. J. Williams, O. H. Biggs, C. S. Lane. THE HUTCHINS SCHOOL MAGAZINE Hobart, Tasmania Number 114 December 1965 CONTENTS PAGE PAGE Visitor and Board of Management 2 Valete -___ __ 19 School Staff 1965 _ 3 Salvete __ 21 School Officers 1965 4 Combined Cadet Notes 22 Editorial __ 5 The Passing Out Parade 23 Chaplain's Notes _ 6 House Notes __ 24 The Old Order Changeth 7 Around the Cloisters 27 Two Generations Back _ 9 Sports Notes __ 33 Exchanges __ 9 Acknowledgment _ 40 Rural England 10 The Middle School 41 Impressions of Tasmania 11 The Junior School Journal 42 School Personalities 13 Editorial Note 47 New Guinea Work Camp 14 The Voice of the School 48 The Parents' Association 14 Old Boys' Notes __ 57 School Activities ___ 15 THE THIRTEENTH HEADMASTER OF THE HUTCHINS SCHOOL, HOBART, DAVID R. LAWRENCE 2 3 SCHOOL STAFF 1965 Headmaster: D. -

Seacare Authority Exemption

EXEMPTION 1—SCHEDULE 1 Official IMO Year of Ship Name Length Type Number Number Completion 1 GIANT LEAP 861091 13.30 2013 Yacht 1209 856291 35.11 1996 Barge 2 DREAM 860926 11.97 2007 Catamaran 2 ITCHY FEET 862427 12.58 2019 Catamaran 2 LITTLE MISSES 862893 11.55 2000 857725 30.75 1988 Passenger vessel 2001 852712 8702783 30.45 1986 Ferry 2ABREAST 859329 10.00 1990 Catamaran Pleasure Yacht 2GETHER II 859399 13.10 2008 Catamaran Pleasure Yacht 2-KAN 853537 16.10 1989 Launch 2ND HOME 856480 10.90 1996 Launch 2XS 859949 14.25 2002 Catamaran 34 SOUTH 857212 24.33 2002 Fishing 35 TONNER 861075 9714135 32.50 2014 Barge 38 SOUTH 861432 11.55 1999 Catamaran 55 NORD 860974 14.24 1990 Pleasure craft 79 199188 9.54 1935 Yacht 82 YACHT 860131 26.00 2004 Motor Yacht 83 862656 52.50 1999 Work Boat 84 862655 52.50 2000 Work Boat A BIT OF ATTITUDE 859982 16.20 2010 Yacht A COCONUT 862582 13.10 1988 Yacht A L ROBB 859526 23.95 2010 Ferry A MORNING SONG 862292 13.09 2003 Pleasure craft A P RECOVERY 857439 51.50 1977 Crane/derrick barge A QUOLL 856542 11.00 1998 Yacht A ROOM WITH A VIEW 855032 16.02 1994 Pleasure A SOJOURN 861968 15.32 2008 Pleasure craft A VOS SANTE 858856 13.00 2003 Catamaran Pleasure Yacht A Y BALAMARA 343939 9.91 1969 Yacht A.L.S.T. JAMAEKA PEARL 854831 15.24 1972 Yacht A.M.S. 1808 862294 54.86 2018 Barge A.M.S. -

60 Great Short Walks 60 60 Great Short Walks Offers the Best of Tasmania’S Walking Opportunities

%JTDPWFS5BTNBOJB 60 Great Short Walks 60 60 Great Short Walks offers the best of Tasmania’s walking opportunities. Whether you want a gentle stroll or a physical challenge; a seaside ramble or a mountain vista; a long day’s outing or a short wander, 60 Great Short Walks has got plenty for you. The walks are located throughout Tasmania. They can generally be accessed from major roads and include a range of environments. Happy walking! 60 Great Short Walks around Tasmania including: alpine places waterfalls Aboriginal culture mountains forests glacial lakes Above then clockwise: beaches Alpine tarn, Cradle Mountain-Lake tall trees St Clair National Park seascapes Mt Field National Park Cradle Mountain, history Cradle Mountain-Lake St Clair National Park islands Lake Dove, Cradle Mountain-Lake St Clair wildlife National Park and much more. Wineglass Bay, Freycinet National Park 45 47 46 33 34 35 38 48 Devonport 39 50 49 36 41 Launceston 40 51 37 29 30 28 32 31 42 44 43 27 52 21 20 53 26 24 57 Strahan 19 18 54 55 23 22 56 25 15 14 58 17 16 Hobart 60 59 1 2 Please use road 3 13 directions in this 4 5 booklet in conjunction 12 11 6 with the alpha-numerical 10 7 system used on 8 Tasmanian road signs and road maps. 9 45 47 46 33 34 35 38 48 Devonport 39 50 49 36 41 Launceston 40 51 37 29 30 28 32 31 42 44 43 27 52 21 20 53 26 24 57 Strahan 19 18 54 55 23 22 56 25 15 14 58 17 16 Hobart 60 59 1 2 3 13 4 5 12 11 6 10 7 8 9 Hobart and Surrounds Walk Organ Pipes, Mt Wellington Hobart 1 Coal Mines Historic Site Tasman Peninsula 2 Waterfall Bay Tasman -

3966 Tour Op 4Col

The Tasmanian Advantage natural and cultural features of Tasmania a resource manual aimed at developing knowledge and interpretive skills specific to Tasmania Contents 1 INTRODUCTION The aim of the manual Notesheets & how to use them Interpretation tips & useful references Minimal impact tourism 2 TASMANIA IN BRIEF Location Size Climate Population National parks Tasmania’s Wilderness World Heritage Area (WHA) Marine reserves Regional Forest Agreement (RFA) 4 INTERPRETATION AND TIPS Background What is interpretation? What is the aim of your operation? Principles of interpretation Planning to interpret Conducting your tour Research your content Manage the potential risks Evaluate your tour Commercial operators information 5 NATURAL ADVANTAGE Antarctic connection Geodiversity Marine environment Plant communities Threatened fauna species Mammals Birds Reptiles Freshwater fishes Invertebrates Fire Threats 6 HERITAGE Tasmanian Aboriginal heritage European history Convicts Whaling Pining Mining Coastal fishing Inland fishing History of the parks service History of forestry History of hydro electric power Gordon below Franklin dam controversy 6 WHAT AND WHERE: EAST & NORTHEAST National parks Reserved areas Great short walks Tasmanian trail Snippets of history What’s in a name? 7 WHAT AND WHERE: SOUTH & CENTRAL PLATEAU 8 WHAT AND WHERE: WEST & NORTHWEST 9 REFERENCES Useful references List of notesheets 10 NOTESHEETS: FAUNA Wildlife, Living with wildlife, Caring for nature, Threatened species, Threats 11 NOTESHEETS: PARKS & PLACES Parks & places, -

Eucryphiaeucryphia December 2017 1

EucryphiaEucryphia December 2017 1 Volume 22 No.8 December 2017 Journal of the Australian Plants Society Tasmania Gaultheria hispida ISSN 1324-3888 2 Eucryphia December 2017 EUCRYPHIA Contents ISSN 1324-3888 Published quarterly in Membership subs. & renewals 3 March, June, September and December by Membership 4 Australian Plants Society Tasmania Inc Editorial 4 ABN 64 482 394 473 President’s Plot 5 Patron: Her Excellency, Professor the Honourable Kate Warner, AC, Council Notes 6 Governor of Tasmania Study Group Highlights 7 Society postal address: PO Box 3035, Ulverstone MDC Tas 7315 Invitation 8 Editor: Mary Slattery ‘Grass Roots to Mountain Tops’ 9 [email protected] Contributions and letters to the editor Strategic Planning for our Future 10 are welcome. If possible they should be forwarded by email to the editor at: Blooming Tasmania 11 [email protected] or typed using one side of the paper only. Recent Name Changes 13 If handwritten, please print botanical names and the names of people. Calendar for 2018 16 Original text may be reprinted, unless otherwise indicated, provided an Annual General Meeting agenda 17 acknowledgment of the source is given. Permission to reprint non-original material New Membership Application 20 and all drawings and photos must be obtained from the copyright holder. Ants in Your Plants part B 24 Views and opinions expressed in articles are those of the authors and are not Kingston Stormwater Wetlands 30 necessarily the views and/or opinions of the Society. Why Is It So? 33 Next issue in March -

Assessment Report

Assessment Report Forestry Tasmania T/A Sustainable Timber Tasmania AS 4708; AS 4810; ISO 14001 and PEFC ST 2002:2013 August 2019 Assessment dates 01/08/2019 to 18/10/2019 (Please refer to Appendix for details) Assessment Location(s) Hobart (001), Geeveston (002), Scottsdale (003), Derwent Park (004), Perth (009), New Norfolk (011), Bell Bay (020) Report Author Ross Garsden Assessment Standard(s) AFS 4708:2013, ISO 14001:2015, AS/NZS 4801:2001, PEFC ST 2002:2013 Page 1 of 84 Assessment Report. Table of contents Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................................... 3 Changes in the organization since last assessment ............................................................................................. 4 Your next steps ................................................................................................................................................ 4 NCR close out process .................................................................................................................................. 4 Assessment objective, scope and criteria ........................................................................................................... 5 Statutory and regulatory requirements ............................................................................................................... 5 Assessment Participants ................................................................................................................................... -

AFG Winter 2009.Indd

The world’s tallest hardwood tree The world’s tallest hardwood tree was discovered earlier this year in Tasmanian state forest less than less than five STILL STANDING kilometres from Forestry Tasmania’s Tahune Airwalk tourism attraction. orestry Tasmania staff Mayo Kajitani and David Mannes were routinely screening some new Fairborne laser scanner (LiDAR ) data taken last August for giant trees when they found a large canopy whose maximum height reading was showing 99 metres. Scarcely containing their excitement, they raced to the Huon River to check their giant, a mountain ash (Eucalyptus regnans), from the ground. Using special ground-based laser survey equipment, they got clear sightings to just below the top of the tree, giving readings of its height at over 100 metres. “I had been saving the name Centurion for our 100th giant tree”, says David. “None of us ever imagined that we would find a 100 metre tree instead.” A Centurion was the title given to a Roman officer in charge of 100 soldiers. While it was initially thought to be the only known standing hardwood tree in the world to be over 100 metres tall, subsequent, more accurate measurements found that it actually measures 99.6m and has a diameter of 405cm. Not quite the full Centurion, but still the tallest Eucalyptus tree in the world, the tallest hardwood tree in the world, and the tallest flowering plant in the world. (Californian redwoods are taller, but they are softwoods, and botanists do not classify them as flowering plants). It has now been nicknamed the Bradman because 99.6 was the legendary Australian cricketer’s test run average. -

Tassie's Parks and Nature

Tassie's Parks and Nature Your itinerary Start Location Visited Location Plane End Location Cruise Train Over night Ferry Day 1 beauty you’ve seen today with local beer and wine or continue your exploration Welcome to Hobart on the property’s wilderness boardwalk. Be sure to check out the hotel’s art gallery that showcases the Cradle Mountain wilderness through the works of Hello Hobart! Settle into your hotel opposite Constitution Dock - minutes from Tasmanian artists. the city centre and the perfect base for adventure (flights to arrive prior to 3pm). Then choose how you’d like to spend your first day in the capital of Australia’s Hotel - Cradle Mountain smallest state. Take an easy stroll along the Derwent River or explore Constitution Dock’s many yachts, boats, and fishing trawlers. This lively area, also the finishing Included Meals - Breakfast, Lunch, Dinner line for the annual Sydney to Hobart Yacht Race, is an energizing kick off to your Day 5 Tassie adventures. After getting acquainted with the city, join your Travel Director and group for a Welcome Reception including Tasmanian cuisine such as fresh Explore Dramatic Cradle Mountain Pacific oysters, catch of the day, and grain-fed beef paired with local wines and Waking in the heart of Cradle Mountain National Park, get ready to explore more beer. It’s a fresh and delicious start to your adventures in beautiful Tassie. of this beautiful, protected landscape. You’ll begin at Waldheim Chalet for a bit of history. Learn how after summiting the peak, Gustav Weindorfer and his wife Kate Hotel - Grand Chancellor were compelled to build Waldheim (meaning “home in the forest”) Chalet to give tourists the opportunity to enjoy the natural surroundings. -

The Rotary Line Board of Directors

Rotary Club of RI President Gary C K Huang │ District 9830 Governor: Ken Moore Huon Valley Inc. P O Box 19 Huonville Tasmania 7109 2014-2015 The Rotary Line Board of Directors 29 July 2014 Meeting # 1056 Volume 25, Issue 4 President: Meeting Chair Person: PP Tricia Reardon Trudy Griffiths Registration Officer: PP Ray Clements Club Captain Jul-Oct Bill Newham Club Captain Nov-Feb Welcome to our Youth Exchange Student: PP Peter Clark Club Captain Mar-Jun Carole Bouverat from Switzerland Trevor Weller Secretary: We extend a very warm welcome to Carole on her first trip to our Rotary Club and to the Huon PP Tricia Reardon Valley. Carole, commenced at Hobart College yesterday and is currently staying with PP Peter Treasurer: Clark’s family before moving to her first host family. PP John Walduck Avenues of Service Directors A Letter from International PolioPlus Committee Club Service: PP Ray Clements I am happy to announce that we ing. This is a chance for Rotarians, eradication, will take place on World Community Service: successfully met our fundraising goal clubs, and districts across the world Polio Day- 24 October 2014—at Bill Newham for Rotary Year 2013-14. While it is to come together to fight polio. There 18:30pm CDT and will be streamed Vocational Service: important to celebrate our success, are many ways you could mark the live at Neil Purdom we recognize that we still need to day. Dedicate your club meeting to endpolionow.org. I encourage your raise funds and awareness for polio Youth Service: focus on Rotary’s work to end polio club/district to have a viewing party Kareen Brandt eradication. -

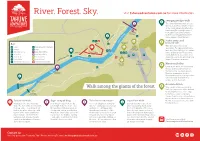

River. Forest. Sky. Visit Tahuneadventures.Com.Au for More Information

River. Forest. Sky. Visit tahuneadventures.com.au for more information Swinging Bridges Walk 5 2 This three-kilometre track crosses the Huon and Picton Rivers. Pause at the viewing platform where the rivers meet. Discover the ruins of Eagle Hang Constable Francis McPartlan’s r Gliding k e 1870s house. Imagine living here al v 4 W i e R alone, deep in the wilderness. in P n n o o u u Visitor centre and H Visitor centre 8 6 Key Entry H and café licensed cafe Take a break to enjoy local Toilets Walk (gentle hill some steps) Exit 1 6 specialties. Try salmon and honey – Parking Steps AirWalk Lodge 5 and Cabin taste the Huon Valley’s cool-climate Wheelchair access Eagle Hang Gliding T Cantilever ahune AirWalk Tahune wines and local cider. Pause for a Information Eagle Hang Gliding Bridge snack, light meal, tea, coffee or ice alk Gas barbeque Accommodation es W idg cream. Browse in the gift shop for a g Br Huo Picnic Shelter Historical ruins gin n in Riv unique Huon pine memento. w er 7 Walk (wheelchair access) Shuttle service available S Main Bluestone Bluestone Shelter Shelter Entrance 7 3 Learn more about the fascinating Ar ve history and natural heritage of Ro Tasmania’s far southern region. Twin Rivers ad Adventure Meet an interpretive guide to 5 discover the stories of the pioneers who lived and worked in the forests and on the rivers. Viewing platform Swinging Accommodation Bridges 8 Walk among the giants of the forest Stay a night or two and enjoy an owl’s eye experience of the AirWalk by torchlight. -

Prose Itinerary

SCHOOL TASMANIA TOUR Prose Itinerary Day 1: School – Melbourne ~ Spirit of Tasmania ~ Bass Strait Did you know Tasmanian devils once lived on mainland Australia 600 years ago? Did you know the first parking meters in Australia were installed in Collins Street, Hobart in 1955? And did you know the first telephone call in Australia was made in Tasmania between Launceston and Campbell Town? Discover many more interesting facts on your tour of Tasmania. Depart school at 8.00am to arrive in Melbourne at 3.00pm for an early dinner before boarding the Spirit of Tasmania for the overnight cruise to Devonport departing at 7.30pm. Explore the vessel or relax in your multi- share cabin with private facilities. Day 2: Sheffield ~ Cradle Mountain ~ Port Sorell BLD Rise and shine!! Welcome to Tasmania. Disembark in Devonport about 6am. and board the coaches with the first port of call being breakfast. Travel through fertile farmland to Sheffield – the town of murals where close to 50 life-like paintings decorate shops and buildings. Our next stop is the famous Cradle Mountain National Park and a walk around the picturesque Dove Lake. Join a ranger guided tour discovering the unique flora and fauna, history and challenges that makes this World Heritage Park what it is today. Travel back to the north coast to the port town of Burnie, the site of the now closed paper milling industry before traveling to the coastal township of Port Sorell. Day 3: Midlands Highway ~ Tasman Peninsula ~ Port Arthur ~ Ghost Tour BLD Turning south today travel down the historic Midland Highway passing through Campbell Town and onto the Tasman Peninsula and onto the Port Arthur.