Spring-Migration Ecology of Northern Pintails in South-Central Nebraska

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Effects of the Wetlands Reserve Program on Waterfowl Carrying Capacity in the Rainwater Basin Region of South-Central Nebraska

Effects of the Wetlands Reserve Program on Waterfowl Carrying Capacity in the Rainwater Basin Region of South-Central Nebraska A Conservation Effects Assessment Project Wildlife Component assessment Submitted to: Charlie Rewa, USDA Natural Resource Conservation Service Diane Eckles, USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service Skip Hyberg, USDA Farm Service Agency Sally Benjamin, USDA Farm Service Agency Submitted by: Andrew A. Bishop U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Habitat and Population Evaluation Team 203 West 2nd Street Grand Island, Ne 68801 [email protected] and Mark Vrtiska Waterfowl Program Manager Nebraska Game and Parks Commission 2200 North 33rd Street Lincoln, Ne 68503 May 8, 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .............................................................................................. 1 INTRODUCTION............................................................................................................. 2 Background......................................................................................................................... 2 Justification..................................................................................................................... 4 METHODS ........................................................................................................................ 5 Data Development and Analysis..................................................................................... 6 Component 1: Deliniate easement boundary ............................................................ -

Habitat Assessment for Nebraska's At-Risk Species

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Nebraska Game and Parks Commission -- White Nebraska Game and Parks Commission Papers, Conference Presentations, & Manuscripts 8-2014 Habitat Assessment for Nebraska's At-risk Species: Descriptions of Species Models used in the CHAT (Crucial Habitat Assessment Tool) Species of Concern Data Layer Rachel Simpson Rick Schneider Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nebgamewhitepap Part of the Biodiversity Commons This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Nebraska Game and Parks Commission -- White Papers, Conference Presentations, & Manuscripts by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Habitat Assessment for Nebraska’s At-risk Species: Descriptions of Species Models used in the CHAT (Crucial Habitat Assessment Tool) Species of Concern Data Layer Rachel Simpson and Rick Schneider Nebraska Natural Heritage Program, Nebraska Game and Parks Commission Lincoln, NE August 2014 Introduction As part of an effort across the western U.S. states led by the Western Governors’ Association, the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission synthesized information related to habitat for at-risk native species and natural plant communities. The result, submitted to the WGA in the fall of 2013, is coarse- scale, landscape-level information that can be used by anyone for land-use planning. The product of this west-wide collaboration is called the Crucial Habitat Assessment Tool (CHAT). The information, provided through an online GIS-mapping tool, is non-regulatory and gives project planners and the general public access to credible scientific data on a broad scale for use in project analysis, siting, and planning. -

Fact Sheet, Proposed Expansion of the Rainwater Basin Wetland

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Proposed Expansion of the Rainwater Basin Wetland Management District Conserving the Rainwater Basin The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Ser- vice) is proposing to expand protection of the Rainwater Basin in southeastern Nebraska. This unique and highly di- verse area is internationally known for its spectacular bird migrations. The Rainwater Basin Wetland Manage- ment District (district) was established in 1963 with a goal of acquiring 24,000 acres to support large bird concentra- tions along the central flyway, especially during spring migration. At that time, the landscape was quite different than it is today, and the conversion of the area’s wetlands occurred more rapidly than anticipated. During the nearly 50 years since the district was established, irrigation technology has changed the landscape from diverse croplands, small fields, pastures, and wetlands to inten- sively farmed corn and soybean fields. A waterfowl production area in the late spring Many of the wetlands and nearly all of the pastureland are gone. The joint venture identified three fac- production areas in the Rainwater Ba- To date, the Service has acquired tors that would influence the selection sin are managed mainly for migratory 22,023 acres of the 24,000 acres approved of lands to be acquired: birds and were purchased primarily in 1963. The district also manages an ■■ the number of privately owned wet- with Duck Stamps. additional 4,505 acres donated by or land acres that affect management Conservation easements would focus obtained from other agencies, primar- of adjoining acres owned by the on smaller, temporary wetlands located ily the Farmers Home Administration, Service or the Nebraska Game and in cropland and grassland. -

Sandhill Stats Spread of Invasives Like Red Cedar Are Causing Habitat Loss Location: North-Central Nebraska and Fragmentation Throughout the Sandhills

United States Department of Agriculture SANDHILLS PROJECT A HOSTILE TAKEOVER The Sandhills landscape of Nebraska is speckled with lakes, wetlands, wet meadows, spring-fed streams - and unfortunately - too many eastern red cedar trees. The 19,300-square-mile grass-covered sand dune formation in north-central Nebraska serves as an oasis for wildlife, including the greater prairie-chicken and American burying beetle. The Sandhills are also critically important to waterfowl, Photos by Aaron Price, USDA Price, Aaron by Photos who nest in the region. The conversion of rangelands to cultivated crops and the Sandhill Stats spread of invasives like red cedar are causing habitat loss Location: North-Central Nebraska and fragmentation throughout the Sandhills. To reverse Habitat Type: Grassland, wetlands, wet-meadows the loss and fragmentation of habitat, NRCS is working Target Species: Greater Prairie Chicken and with agricultural producers to install grazing management American Burying Beetle practices to improve rangeland health and wildlife habitat. Other Species: Western Prairie Fringed Orchid, Dicksissel, Eastern Meadowlark, Field Sparrow, Grasshopper Sparrow, Swainson’s Hawk, Monarch LANDOWNERS ARE PART OF THE SOLUTION Butterfly, Upland Sandpiper, Western Meadowlark, Sharp-tailed Grouse and Regal Fritillary Butterfly Landowners in Nebraska are helping restore the Sandhill Partners: Landowners, Sandhills Task Force, landscape by improving the health of rangelands using Nebraska Cattlemen, Rainwater Basin Joint prescribed grazing and removing invading cedar trees. Venture, Nebraska Game and Parks, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Pheasants Forever Natural Resources Conservation Service Working Lands for Wildlife SANDHILLS PROJECT Through grazing management, mechanical removal and prescribed burning, producers can manage this threat to the landscape as cedar trees shade out other plants, which degrades the quality of forage for livestock and habitat for wildlife. -

Sandhill Cranes Converge Crane Migration in the Spring

TOURIST INFORMATION CENTERS Grand Island/Hall County Convention & Visitors Bureau Central 2424 S Locust St, Ste. C • Grand Island, NE 68801 8:30 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. Monday-Friday 308.382.4400 • 800.658.3178 visitgrandisland.com Nebraska Hastings/Adams County Convention & Visitors Bureau 219 N Hastings Ave • Hastings, NE 68902 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Monday-Friday WILDLIFE 402.461.2370 • 800.967.2189 visithastingsnebraska.com VIEWING GUIDE Kearney Visitors Bureau 1007 2nd Avenue • Kearney, NE 68847 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. Monday-Friday 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. Saturday 1 p.m. to 4 p.m. Sunday (6 weeks during Crane Season) 308.237.3178 • 800.652.9435 • visitkearney.org US Fish & Wildlife Service Rainwater Basin Wetland Management District 73746 V Road • Funk, NE 68940 308.263.3000 fws.gov/refuge/rainwater_basin_wmd WILDLIFE VIEWING INFORMATION CENTERS Crane Trust Nature & Visitor Center I-80 Exit 305 (Alda) 308.382.1820 • cranetrust.org Fort Kearny State Historical Park 1020 V Road • Kearney, NE 68847 308.865.5305 • outdoornebraska.gov/fortkearny Iain Nicolson Audubon Center at Rowe Sanctuary I-80 Exit 285 308.468.5282 • rowe.audubon.org US Fish & Wildlife Service Rainwater Basin Wetland Management District 73746 V Road • Funk, NE 68940 308.263.3000 fws.gov/refuge/rainwater_basin_wmd NebraskaFlyway.com 18CNWG_30K THE GREAT MIGRATION THE GREAT MIGRATION NEBRASKA’S PLATTE RIVER CRANE VALLEY TRUST Each spring, something magical happens in the The Crane Trust Nature & Visitor Center welcomes guests to heart of the Great Plains. More than 80 percent of rare, protected lands year round—and to the great sandhill the world’s population of sandhill cranes converge crane migration in the spring. -

Birding Nebraska's Central Platte Valley and Rainwater Basin Paul A

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Zea E-Books Zea E-Books 12-3-2015 Birding Nebraska’s Central Platte Valley and Rainwater Basin Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska - Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/zeabook Part of the Ornithology Commons Recommended Citation Johnsgard, Paul A., "Birding Nebraska’s Central Platte Valley and Rainwater Basin" (2015). Zea E-Books. Book 36. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/zeabook/36 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Zea E-Books at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Zea E-Books by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. ~~~0 @§m~~~ ~)i~~~~ Paul A. Johnsgard Birding Nebraska’s Central Platte Valley and Rainwater Basin Paul A. Johnsgard Zea Books Lincoln, Nebraska Zea Books are published by the University of Nebraska–Lincoln Libraries Electronic (pdf) ebook edition online at http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/zeabook/ Print edition available from Lulu.com, at http://www.lulu.com/spotlight/unllib The University of Nebraska–Lincoln does not discriminate based on gender, age, disability, race, color, religion, marital status, veteran’s status, national or ethnic origin, or sexual orientation. Birding Nebraska's Central Platte Valley and Rainwater Basin Paul A. Johnsgard Foundation Professor Emeritus, School of Biological Sciences University ofof Nebraska-"-Lincoln,Nebraska-Lincoln, Lincoln, Nebraska 68588-0118 Copyright © 2015, Paul A. Johnsgard Preface*Preface * For naturalists, March is a time for rejoicing, for on its soothing south winds sweep wave after wave of northbound migrant birds. -

NEBRASKA Our Land, Our Water, Our Heritage

NEBRASKA Our Land, Our Water, Our Heritage LWCF Funded Places in LWCF Success in Nebraska Nebraska The Land and Water Conservation Fund (LWCF) has provided funding Federal Program to help protect some of Nebraska’s most special places and ensure Agate Fossil Beds NM recreational access for hunting, fishing and other outdoor activities. Boyer Chute NWR Nebraska has received approximately $57.3 million in LWCF funding Homestead NM over the past five decades, protecting places such as the Rainwater Niobrara NSR Basin Wildlife Management Area, Boyer Chute National Wildlife Rainwater Basin WMA Refuge and Agate Fossil Beds National Monument. Scotts Bluff NM Federal Total $ 7,100,000 Forest Legacy Program (FLP) grants are also funded under LWCF, to help protect working forests. The FLP cost-share funding supports Forest Legacy Program timber sector jobs and sustainable forest operations while enhancing $ 383,000 wildlife habitat, water quality and recreation. For example, the FLP contributed to places such as the Pine Ridge Forest in Dawes County. Habitat Conservation (Sec. 6) The FLP assists states and private forest owners to maintain working $ 2,200,000 forest lands through matching grants for permanent conservation easement and fee acquisitions, and has leveraged approximately State Program $380,000 in federal funds to invest in Nebraska’s forests, while Total State Grants $ 47,628,000 protecting air and water quality, wildlife habitat, access for recreation and other public benefits provided by forests. Total $ 57,300,000 LWCF state assistance grants have further supported hundreds of projects across Nebraska’s state and local parks Ponca State Park in Dixon County and Walnut Grove Park in Omaha. -

Terrestrial Ecological Systems and Natural Communities of Nebraska

Terrestrial Ecological Systems and Natural Communities of Nebraska (Version IV – March 9, 2010) By Steven B. Rolfsmeier Kansas State University Herbarium Manhattan, KS 66506 and Gerry Steinauer Nebraska Game and Parks Commission Aurora, NE 68818 A publication of the NEBRASKA NATURAL HERITAGE PROGRAM NEBRASKA GAME AND PARKS COMMISSION LINCOLN, NEBRASKA 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter 1: Introduction..................................................................................… 1 Terrestrial Ecological System Classification…...................................................... 1 Ecological System Descriptions…………............................................................. 2 Terrestrial Natural Community Classification……………………………….….. 3 Vegetation Hierarchy………………………….………………………………… 4 Natural Community Nomenclature............................................................…........ 5 Natural Community Ranking..;……………….……….....................................…. 6 Natural Community Descriptions………….......................................................... 8 Chapter 2: Ecological Systems of Nebraska.………………………………… 10 Upland Forest, Woodland, and Shrubland Systems…………………………….. 10 Eastern Upland Oak Bluff Forest……….……………………………….. 10 Eastern Dry-Mesic Bur Oak Forest and Woodland……………………… 12 Great Plains Dry Upland Bur Oak Woodland…………………………… 15 Great Plains Wooded Draw, Ravine and Canyon……………………….. 17 Northwestern Great Plains Pine Woodland……………………………… 20 Upland Herbaceous Systems…………………………………………………….. 23 Central Tall-grass Prairie……………………………………………….. -

Size Elevation Geographic Regions

NEBRASKA : THE COR NHUSKER STATE 25 LAND AND CLIMATE10 Size Nebraska measures 459 miles (740 kilometers) across at its widest point, following a diagonal from southeast to northwest. Nebraska’s total area, including land and water, is 77,358 square miles (200,358 square kilometers) — almost 20 percent larger than New England. The state’s land area alone is 76,878 square miles (199,113 square kilometers). Nebraska ranks 16th among the states in land and water area and 15th in land area alone. Elevation Nebraska’s elevation rises gradually from southeast to northwest in a series of roll- ing plateaus. The lowest point, 840 feet (256 meters) above sea level, is in southeastern Richardson County at the Missouri River. The highest point, 5,424 feet (1,654 meters) above sea level, is in southwestern Kimball County. Nebraska’s average elevation is 2,600 feet (793 meters). Geographic Regions Nebraska has two major geographic regions — the Dissected Till Plains and the Great Plains. The Great Plains can be divided into smaller areas, among them the Loess Plains, the Loess Hills, the Sandhills and the High Plains. The Dissected Till Plains formed when Ice Age glaciers left behind a rich soil- forming material, called till, over the eastern fifth of the state. Windblown dust (loess) later settled on the till, and over the years, streams dissected the region, forming a roll- ing terrain. Along the Missouri River, the terrain includes bluffs and river-deposited lowlands. This combination makes the Dissected Till Plains well-suited for farming. The Great Plains stretch west across the rest of the state. -

Rainwater Rainwater Basin

Rainwater Basin landscape occupies parts of 17 counties in south-central Nebraska. The topography is flat to gently rolling loess plain. The surface water drainage system is poorly developed and many watersheds drain into low-lying wetlands. Soil survey maps from the early 1900s indicate that approximately 4,000 larger wetlands totaling nearly 100,000 acres occurred in the region prior to Euro-american settlement. By the beginning of the 20 th Century most uplands in the landscape had been converted to cropland. A 1983 survey indicated that only ten percent of the original wetlands had not been drained or filled. Nearly all remaining Rainwater Basin wetlands have been farmed at some time in the last century. The Rainwater Basin has been recognized as a significant migratory bird area. The wetlands have been identified by the North American Waterfowl Management Plan as a waterfowl habitat area of major concern in North America. The basins are a concentration point in the central flyway for spring migrating ducks, geese, and shorebirds. They also provide important migration habitat for whooping cranes, bald eagles, and many other bird species. It is estimated that nearly the entire North American population of buff-breasted sandpipers stage in the eastern Rainwater Basins during their spring migration. In fact, the Western Hemisphere Shorebird Reserve Network (WHSRN) designated the Rainwater Basin as its first landscape of hemispheric importance. These wetlands are also important to taxonomic groups besides birds. Muskrats thrive in the basin marshes. And, wetlands in the Rainwater Basin serve as breeding sites for amphibian species. Natural Legacy Demonstration Site Kissinger Basin Wildlife Management Area – Nebraska Game and Parks Commission The Kissinger Basin Wildlife Management Area is located one mile north of Fairfield, Clay County in the Rainwater Basin Biologically Unique Landscape. -

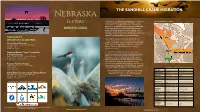

Nebraska the SANDHILL CRANE MIGRATION Flyway Each Spring, Something Magical Happens in the Heart the CENTRAL FLYWAY of the Great Plains

Nebraska THE SANDHILL CRANE MIGRATION Flyway Each spring, something magical happens in the heart THE CENTRAL FLYWAY of the Great Plains. More than 80% of the world’s population of sandhill cranes converge on Nebraska’s BIRDING GUIDE Platte River Valley – a critical sliver of threatened habitat in North America’s Central Flyway. Along with the cranes come millions of migrating ducks and geese filling the neighboring rainwater basins. COMMUNITY The sandhill cranes come to rest and refuel for a INFORMATION CENTERS month as they prepare for the arduous journey to vast Grand Island Tourism breeding grounds in Canada, Alaska and Siberia. They 201 W. 3rd Street | Grand Island, NE 68801 arrive from far-flung wintering grounds in northern 308-382-4400 Mexico, Texas, and New Mexico on a journey of VisitGrandIsland.com thousands of miles. Hastings/Adams County Convention For centuries, the birds have come to rest and & Visitors Bureau restore themselves. The shallow, braided channels of 219 N. Hastings Avenue | Hastings, NE 68901 Nebraska’s Platte River provide safe nighttime roost 402-461-2370 | 800-967-2189 sites. Waste grain in nearby fields provides food to VisitHastingsNebraska.com build up depleted fat reserves needed for continuing their migration. Adjacent wet meadows provide Kearney Visitors Bureau nutrients and secluded loafing areas for rest, bathing, 1007 2nd Avenue | Kearney, NE 68847 and courting. During their stop in Nebraska, sandhill 308-237-3178 cranes gain approximately 15% of their body weight. SANDHILL CRANE WHOOPING CRANE VisitKearney.org Plan your visit to see this migration for yourself HEIGHT 3-4 feet 5 feet North Platte/Lincoln County Visitors Bureau using the information on the following pages WINGSPAN 6 feet 7.5 feet 101 Halligan Drive | North Platte, NE 69101 308-532-4729 | 800.955.4528 of this brochure. -

Wetland Program Plan for Nebraska

1 Wetland Program Plan for Nebraska By: Ted LaGrange, Wetland Program Manager Nebraska Game and Parks Commission P.O. Box 30370 Lincoln, NE 68503 (402) 471-5436 [email protected] October 14, 2010 This Plan was approved by EPA in December 2010 OUTLINE Table of Contents OVERALL GOAL AND TIME FRAME ............................................................................. 2 ACTION ITEM SUMMARY .............................................................................................. 3 Partnership Action Items .............................................................................................. 3 Monitoring and Assessment Action Items .................................................................... 3 Regulation Action Items ............................................................................................... 3 Voluntary Protection and Restoration Action Items...................................................... 4 Wetland Management Action Items ............................................................................. 6 Water Quality Standards Action Items ......................................................................... 6 Outreach and Education Action Items ......................................................................... 6 Information Needs Action Items ................................................................................... 7 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 7 Wetland Definition