Tell Me a Story

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Round 8 2021 Row Volume 2 · Issue 8

The FRONT ROW ROUND 82021 VOLUME 2 · ISSUE 8 Stand by your Mann Newcastle's five-eighth on his side's STATS season defining run of games ahead Two into one? Why the mooted two-conference NOT system for the NRL is a bad call. GOOD WE ANALYSE EXACTLY HOW THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC HAS INFLUENCED THE GAME INSIDE: NRL Round 8 program with squad lists, previews & head to head stats, Round 7 reviewed LEAGUEUNLIMITED.COM AUSTRALIA’S LEADING INDEPENDENT RUGBY LEAGUE WEBSITE THERE IS NO OFF-SEASON 2 | LEAGUEUNLIMITED.COM | THE FRONT ROW | VOL 2 ISSUE 8 What’s inside From the editor THE FRONT ROW - VOL 2 ISSUE 8 Tim Costello From the editor 3 Last week, long-serving former player and referee Henry Feature What's (with) the point(s)? 4-5 Perenara was forced into medical retirement from on-field Feature Kurt Mann 6-7 duties. While former player-turned-official will remain as part of the NRL Bunker operations, a heart condition means he'll be Opinion Why the conference idea is bad 8-9 doing so without a whistle or flag. All of us at LeagueUnlimited. NRL Ladder, Stats Leaders. Player Birthdays 10 com wish Henry all the best - see Pg 33 for more from the PRLMO. GAME DAY · NRL Round 8 11-27 Meanwhile - the game rolls on. We no longer have a winless team LU Team Tips 11 with Canterbury getting up over Cronulla on Saturday, while THU Canberra v South Sydney 12-13 Penrith remain the high-flyers, unbeaten through seven rounds. -

Redfern Oval - Licence Agreement with the South Sydney Rabbitohs

FINANCE, PROPERTIES AND TENDERS COMMITTEE 10 SEPTEMBER 2007 ITEM 7. REDFERN OVAL - LICENCE AGREEMENT WITH THE SOUTH SYDNEY RABBITOHS FILE NO: 5264950 SUMMARY Redfern Park is being redeveloped to substantially upgrade the historic passive park area, to provide an attractive open quality playing field accessible to the public, a low rise grandstand containing amenities and change rooms (including space for the Rabbitohs), a kiosk/café and meeting room designed to meet the Council’s environmental targets. The South Sydney District Rugby League Football Club (Rabbitohs) has played or trained rugby league at Redfern Oval since the club was founded in 1908. In 2006, Council adopted the Redfern Park Plan of Management which committed to entering into a Licence Agreement with the Rabbitohs for the use of Redfern Oval and its associated facilities for the purposes of training for rugby league football and up to eight pre-season or exhibition matches. It is proposed that the Rabbitohs return to Redfern Oval once completed under a formal licence agreement for a period of 20 years (2x10). There will also be provision for passive and active community use of the field and facilities as designated public space. Bookings and access will be managed by Council. The proposed Licence is required to be advertised for public comment for a period of 28 days in accordance with the Local Government Act 1993 before being considered for approval by Council. It is also proposed that Council now enter into an Agreement to Grant Licence containing provisions for the statutory process to be completed prior to a Licence being granted. -

Realising the Potential Vision

Redfern-Waterloo Authority 2009-10 Annual Report Realising the potential Vision The vision of the Redfern-Waterloo Authority (RWA) is to establish Redfern-Waterloo as an active, vibrant and sustainable community by promoting and supporting greater social cohesion and community safety, respect for the cultural heritage, and the orderly development of the area in consideration of social, economic, ecological and other sustainable development. In 2001, the NSW Government made a commitment to revitalise Key highlights for Redfern-Waterloo in the Redfern and Waterloo area through a ‘partnership’ with the local community focused on delivering strategic urban renewal, 2009 – 2010: improved human services and job creation. Three years later, • Then Prime Minister, Kevin Rudd officiated at the the Government created the Redfern-Waterloo Authority Act opening of Australia’s one-of-a-kind Aboriginal youth 2004 No 107 and, in January 2005, the Redfern-Waterloo arts, cultural & education facility, the National Centre Authority was established. for Indigenous Excellence; Since then, this partnership has helped changed not only the • face of Redfern-Waterloo, but the perception of the area by Prince William met with Aboriginal leaders at Redfern’s the wider community and, in February 2010, independent data The Block during a three day visit to Australia; was released showing a reduction in local crime combined with • Yaama Dhiyaan – Australia’s only hospitality training centre solid increases in housing prices over the last two years. specialising in Indigenous cuisine – celebrated its third year “What we are seeing in Redfern and Waterloo now are the of success; results of a strong partnership between Government and the • In just seven short months, the Eveleigh Farmers’ Market community, including local Aboriginal leaders, creating thriving was awarded Sydney’s best; and safe suburbs,” the NSW Premier Ms Keneally said when presenting the data with Police Minister Michael Daley. -

4Th Annual Report for the Year Ended 31 October 2009

4TH ANNUAL REPORT FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 OCTOBER 2009 SOUTH SYDNEY MEMBERS RUGBY LEAGUE FOOTBALL CLUB LTD ACN 118 320 684 ANNUAL REPORT YEAR ENDED 31 OCTOBER 2009 Just one finger. Contents Page 01 Chairman’s Report 3 02 100 Grade Games 4 03 Life Members 6 04 Financials 7 - Directors’ Report 7a, 7b - Lead Auditor’s Independence Declaration 7c - Income Statement - Statement of Recognised Income and Expense 7d - Balance Sheet - Statement of Cash Flow 7e - Discussion and Analysis - Notes to the Financial Statements 7f, 7g - Directors’ Declaration 7h - Audit Report 7h 05 Corporate Partners 8 06 South Sydney District Rugby League Football Club Limited 9 07 NRL Results Premiership Matches 2009 13 NRL Player Record for Season 2009 15 2009 NRL Ladder 15 08 NSW Cup Results 2009 16 09 Toyota Cup Results 2009 17 10 2009 Toyota Cup Ladder 18 The new ‘just one finger’ De–Longhi Primadonna Avant Fully Automatic coffee machine. 2009 Club Awards 18 You would be excited too, with De–Longhi’s range of ‘just one finger’ Fully Automatic Coffee Machines setting a new standard in coffee appreciation. Featuring one touch technology for barista quality Cappuccino, Latte or Flat White, all in the comfort of your own home. All models include automatic cleaning, an in-built quiet grinder and digital programming to personalise your coffee settings. With a comprehensive range to choose from, you’ll be spoilt for choice. www.delonghi.com.au / 1800 126 659 SOUTH SYDNEY MEMBERS RUGBY LEAGUE FOOTBALL CLUB LIMITED 1 ANNUAL REPORT YEAR ENDED 31 OCTOBER 2009 Chairman’s Report 01 My report to Members last year was written In terms of financial performance, I am pleased each of them for the commitment they have on the eve of our return to a renovated and to report that the 2009 year delivered the shown in ensuring that Members’ rights are remodelled Redfern Oval. -

Round 9 2021 Row Volume 2 · Issue 9

The FRONTROUND 9 2021 ROW VOLUME 2 · ISSUE 9 FROM THE START TAKE A TOUR OF RUGBY LEAGUE'S HISTORIC SYDNEY BIRTHPLACES INSIDE: NRL Round 9 program with squad lists, previews & head to head stats, Round 8 reviewed LEAGUEUNLIMITED.COM AUSTRALIA’S LEADING INDEPENDENT RUGBY LEAGUE WEBSITE THERE IS NO OFF-SEASON 2 | LEAGUEUNLIMITED.COM | THE FRONT ROW | VOL 2 ISSUE 9 What’s inside From the editor THE FRONT ROW - VOL 2 ISSUE 9 Tim Costello From the editor 3 A fascinating piece from our historian Andrew Ferguson in this A rugby league history tour of Sydney 4-5 week's issue - a tour of some of Sydney's key historic rugby league locations. Birthplaces of clubs, venues and artefacts NRL Ladder, Stats Leaders. Player Birthdays 6 feature in a wide-range trip across the nation's first city. GAME DAY · NRL Round 9 7-23 On the field and this weekend sees two important LU Team Tips 7 commemorations - on Saturday at Campbelltown the Wests THU South Sydney v Melbourne 8-9 Tigers will done a Magpies-style jersey to honour the life of FRI Penrith v Cronulla 10-11 Tommy Raudonikis following his passing last month. The match day will also feature a Ron Massey Cup and Women's Premiership Parramatta v Sydney Roosters 12-13 double header as curtain raisers, with the Magpies facing Glebe SAT Canberra v Newcastle 14-15 in both matches. Wests Tigers v Gold Coast 16-17 Kogarah will play host to the other throwback with the St George North Queensland v Brisbane 18-19 Illawarra club celebrating the 100th anniversary of St George RLFC. -

Sir Peter Leitch Club at MT SMART STADIUM, HOME of the MIGHTY VODAFONE WARRIORS

Sir Peter Leitch Club AT MT SMART STADIUM, HOME OF THE MIGHTY VODAFONE WARRIORS 5th July 2017 Newsletter #177 Vodafone Warriors v Sea Eagles Bodene Thompson eyes up the Charnze Nicoll-Klokstad scores a try Mafoa’Aeata Hingano and Kieran opposition Foran make a tackle Mafoa’Aeata Hingano looks to pass Nathaniel Roache passes Roger Tuivasa-Sheck and Charnze Nicoll-Klokstad high five Shaun Johnson on the run Simon Mannering gets tackled Young Warriors fans Photos courtesy of www.photosport.nz Manu On The Move By David Kemeys Former Sunday Star-Times Editor, Former Editor-in-Chief Suburban Newspapers, Long Suffering Warriors Fan HAVE BEEN supporting the Vodafone Warriors for so long that Manu Vatuvei was only about 10 when I Igot seriously into it. And if there is a player who polarises opinion more than Manu, I have yet to meet him. So I better declare that I will not hear a bad word said about the bloke. Now it seems the big fellah is going to take up an opportunity to play with Salford, a British club in the UK Super League. Big Manu’s contract with us doesn't expire until the end of the 2018 season, but reports from Guardian rugby league reporter Aaron Bowler say he has signed with the Salford Red Devils. He has been a bit player of late, suffering from a range of injuries, and it is clear other players are more fa- voured nowadays, but it is easy to forget it is only a few years ago we were celebrating Manu becoming the first NRL player to score 10 tries or more every year for a decade, and that he was International Winger of the year in 2008 after the Kiwis’ won the Rugby League World Cup. -

Annual Report South Sydney Member Co

SOUTH SYDNEY MEMBER CO. | | ANNUAL REPORT SOUTH SYDNEY MEMBER CO. | | ANNUAL REPORT FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 OCTOBER 2013 FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 OCTOBER 2013 • 1 2 SOUTH SYDNEY MEMBERS RUGBY LEAGUE FOOTBALL CLUB LIMITED MEMBER CO. SOUTH SYDNEY MEMBERS RUGBY LEAGUE FOOTBALL CLUB LIMITED MEMBER CO. SOUTH SYDNEY MEMBER CO. | | ANNUAL REPORT SOUTH SYDNEY MEMBER CO. | | ANNUAL REPORT FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 OCTOBER 2013 FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 OCTOBER 2013 • • 3 4 SOUTH SYDNEY MEMBERS RUGBY LEAGUE FOOTBALL CLUB LIMITED MEMBER CO. SOUTH SYDNEY MEMBERS RUGBY LEAGUE FOOTBALL CLUB LIMITED MEMBER CO. SOUTH SYDNEY MEMBER CO. | | ANNUAL REPORT SOUTH SYDNEY MEMBER CO. | | ANNUAL REPORT FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 OCTOBER 2013 FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 OCTOBER 2013 • • 2013 NRL RESULTS CHAIRMAN’S REPORT PREMIERSHIP MATCHES 04 AND CLUB AWARDS 29 NRL PLAYER RECORD 100 GRADE GAMES FOR SEASON 2013 AND 05 2013 NRL LADDER 31 CHIEF FINANCIAL NSW CUP RESULTS OFFICER’S REPORT 08 32 2013 HOLDEN CUP FINANCIALS 09 RESULTS 35 2013 HOLDEN CUP CORPORATE PARTNERS 21 LADDER 37 SOUTH SYDNEY DISTRICT RUGBY LEAGUE FOOTBALL LIFE MEMBERS LIMITED 22 39 SUMMARY OF FINANCIALS DIRECTORS’ REPORT PAGE 09 LEAD AUDITOR’S INDEPENDENCE DECLARATION PAGE 11 STATEMENT OF PROFIT OR LOSS AND OTHER COMPREHENSIVE INCOME PAGE 12 STATEMENT OF CHANGES IN EQUITY PAGE 12 STATEMENT OF FINANCIAL POSITION PAGE 13 STATEMENT OF CASH FLOWS PAGE 13 NOTES TO THE FINANCIAL STATEMENTS PAGE 14 DIRECTORS’ DECLARATION PAGE 18 AUDIT REPORT PAGE 19 5 2 SOUTH SYDNEY MEMBERS RUGBY LEAGUE FOOTBALL CLUB LIMITED MEMBER CO. SOUTH SYDNEY MEMBERS RUGBY LEAGUE FOOTBALL CLUB LIMITED MEMBER CO. -

Sir Peter Leitch Club at MT SMART STADIUM, HOME of the MIGHTY VODAFONE WARRIORS

Sir Peter Leitch Club AT MT SMART STADIUM, HOME OF THE MIGHTY VODAFONE WARRIORS 2nd May 2018 Newsletter #215 Vodafone Warriors v Storm Photos courtesy of www.photosport.nz Storm on Song By David Kemeys Former Sunday Star-Times Editor, Former Editor-in-Chief Suburban Newspapers, Long Suffering Warriors Fan HREE BLOKES, an African fellah, a Warriors fan and a guy from Melbourne are all waiting outside the Tmaternity unit to see their new children when the nurse comes out and says: “There has been a terrible mix-up and no one is sure whose baby is whose.” So the three blokes talk about it and the Warriors fan takes the initiative and says he will go first and chose a bby. In he goes and comes out with what is clearly the chid of the African fellah. “What are you doing?” says the African fellah. “Well I couldn’t risk going home with a Storm fan,” says the Warriors man. Boom, boom, which is why it shits me no end that Brad Fittler has come out and said the Storm have to be favourites to win the NRL – back to back – after their showing against us. But it is also why I’m not losing too much sleep over what happened on Anzac Day. Bring on the Tigers and let’s get on with it. Fittler says that 50-10 win was a warning shot fired across the bows of all the other clubs. Brisbane went back to back in 1992-93and it has not happened since. Only a fool, damn it, would ever write Melbourne off, so there slow start meant absolutely nothing. -

12Th Annual Report 100 Grade Games South Sydney Members Rugby League Football Club Limited Page 4

Page 1 Page 2 For the year ended The Rabbitohs have the largest NRL Club Membership in NSW with30,549 Members 12TH 31 October 2017 Cumulative TV audience of 16 million Rated #1 in NSW for combined social media following ANNUAL South Sydney Members Rugby League Football Club Limited Home attendance of 155,436 REPORT ACN 118 320 684 2017 SOUTH SYDNEY MEMBER CO. Page 3 Page 4 Page 5 Contents South Sydney Members Rugby League Football Club Limited Page 2 2017 NRL Premiership Match Chairman’s Report Results and Club 03 Awards 29 NRL Player Records for 100 Grade Games Season 2017 and 2017 04 NRL Ladder 31 2017 NSW Cup Finance Report 07 Results 32 2017 Holden Financials 08 Cup Results 35 2017 Holden Corporate Partners 20 Cup Ladder 38 South Sydney Members Rugby League Football Life Members Club Limited 21 39 Summary of Financials Directors’ report PAGE 08 Lead auditor’s independence declaration PAGE 10 Statement of Profit or Loss and other comprehensive income PAGE 11 Statement of changes in equity PAGE 11 Statement of financial position PAGE 12 Statement of cash flows PAGE 12 Notes to the financial statements PAGE 13 Directors’ declaration PAGE 17 Independent Auditor’s report PAGE 18 Page 3 Chairman’s Report 12th Annual Report 100 Grade Games South Sydney Members Rugby League Football Club Limited Page 4 100 GRADE GAMES FOR SOUTH SYDNEY 1908-2017 Surname First Name Years 1st Grade Games 2nd Grade Games 3rd Grade Games Total Games SUTTON John 2002-17 282 10 18 310 CHAIRMAN’S REPORT COLEMAN Craig 1980-92 209 46 42 297 FENECH Mario 1981-90 181 42 25 248 PIGGINS George 1964-78 112 100 33 245 If sporting clubs are to be measured solely by the performance of their teams on the field, then 2017 was not a year of high achievement for the MERRITT Nathan 2002-03; 2006-14 218 19 2 239 STEVENS Gary 1964-76 162 64 3 229 Rabbitohs. -

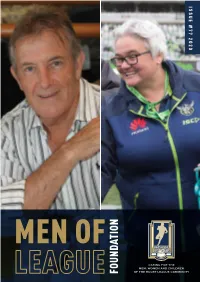

Foundation Licensed Under Cover Driving Range Bar • Functions

ISSUE #77 2020 MEN OF CARING FOR THE MEN, WOMEN AND CHILDREN OF THE RUGBY LEAGUE COMMUNITY FOUNDATION LICENSED UNDER COVER DRIVING RANGE BAR • FUNCTIONS Aces Sporting Club • Springvale Rd & Hutton Rd, Keysborough Ph. 9701 5000 • acessportingclub.com.au • /AcesSportingClub LOOK FORWARD TO REOPENING SOON ✃ PRPREESENTSENT THISTHIS FFLLYEYERR ININ THE THE DRIVING DRIVING RANGE RANGE FOR FOR 200200 BBAALLLLSS FFOORR $$1100 SPOSPORRTTIINGNG CCLULUBB Can not be used in conjunction with any other offer. Terms and Conditions Apply. IN THIS FROM THE OUR COVER Introducing our newest board member Katrina Fanning and recently announced life member Tony Durkin. PROFESSOR THE INSIDE THIS ISSUE 5 McCloy Group corporate membership HONOURABLE 6 Tony Durkin 8 Lionel Morgan STEPHEN MARTIN 11 Katrina Fanning 14 Socially connecting As you read this message, the Foundation brings enormous experience to our board 16 Try July is still unfortunately greatly impacted by as a former Jillaroo, having played 26 Tests 17 Arthur Summons COVID-19 and the necessary restrictions that for Australia and held the roles of president 18 Keith Gee have been imposed by health and government of the Australian Women’s Rugby League 21 Mortimer Wines promotion authorities. Association, chairperson of the Australian 22 Noel Kelly Rugby League Indigenous Council and a 24 Champion Broncos 20 years on The Foundation itself remains in hibernation director of the board of the Canberra Raiders. 26 Ranji Joass mode. Most staff remain stood down, and Welcome Katrina! 34 Phillippa Wade and her Storm Sons we are fortunate that JobKeeper has been 28 Q/A with Peter Mortimer available to us. -

Annual Report W E L C O M in G S P IR IT

2010.11 Annual Report Redfern-Waterloo Authority WELCOMING WELCOMING SPIRIT Redfern-Waterloo Authority REDFERN IS GROWING A decade ago, the NSW Government made a Redfern-Waterloo is the traditional land of the Gadigal commitment to revitalise the Redfern and Waterloo area people of the Eora Nation and remains one of Australia’s through a ‘partnership’ with the local community focused most significant Indigenous communities. It is a thriving on delivering strategic urban renewal, improved human centre for culture, lifestyle and sporting excellence. services and employment opportunities. This vision was realised with the creation of the Redfern-Waterloo Authority Act 2004 No.107 and, in January 2005, the Redfern-Waterloo Authority (RWA) was established. KEY OUTCOMES FOR REDFERN-WATERLOO IN 2010-11 INCLUDE: • The release of the Draft Built Environment Plan • A new Redfern “brand” to help change negative Stage 2 (BEP 2) outlining the proposed planning perceptions of the area and create a platform from framework for the ongoing improvement of social which to promote the region over the long-term as an housing in Redfern, Waterloo and South Eveleigh; exciting destination for business and recreation; • The preparation of the Former Eveleigh Railway • An improved commercial streetscape and enhanced Workshops Interpretation Plan; sense of economic activity as a result of the Roll Up Redfern campaign; and • The establishment of the Sydney Metropolitan Development Authority (SMDA) by the NSW • Further implementation of the Human Services Government to continue the urban renewal initiatives Plan which focuses on improved service delivery of the RWA; for children and families, Aboriginal people, young people, older people, people with disabilities, migrant communities and the homeless. -

South Sydney Member Co. 2014 Annual Report

SOUTH SYDNEY MEMBER CO. | | ANNUAL REPORT SOUTH SYDNEY MEMBER CO. | | ANNUAL REPORT FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 OCTOBER 2014 FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 OCTOBER 2014 • • 3 4 SOUTH SYDNEY MEMBERS RUGBY LEAGUE FOOTBALL CLUB LIMITED MEMBER CO. SOUTH SYDNEY MEMBERS RUGBY LEAGUE FOOTBALL CLUB LIMITED MEMBER CO. SOUTH SYDNEY MEMBER CO. | | ANNUAL REPORT SOUTH SYDNEY MEMBER CO. | | ANNUAL REPORT FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 OCTOBER 2014 FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 OCTOBER 2014 • • 2014 NRL PREMIERSHIP CHAIRMAN’S REPORT MATCH RESULTS AND 03 CLUB AWARDS 29 NRL PLAYER RECORD 100 GRADE GAMES FOR SEASON 2014 AND 06 2014 NRL LADDER 31 2014 NSW CUP FINANCE REPORT 07 RESULTS 34 2014 HOLDEN CUP FINANCIALS 08 RESULTS 35 2014 HOLDEN CUP CORPORATE PARTNERS 20 LADDER 38 SOUTH SYDNEY DISTRICT RUGBY LEAGUE FOOTBALL LIFE MEMBERS LIMITED 21 39 SUMMARY OF FINANCIALS DIRECTORS’ REPORT PAGE 08 LEAD AUDITOR’S INDEPENDENCE DECLARATION PAGE 10 STATEMENT OF PROFIT OR LOSS AND OTHER COMPREHENSIVE INCOME PAGE 11 STATEMENT OF CHANGES IN EQUITY PAGE 11 STATEMENT OF FINANCIAL POSITION PAGE 12 STATEMENT OF CASH FLOWS PAGE 12 NOTES TO THE FINANCIAL STATEMENTS PAGE 13 DIRECTORS’ DECLARATION PAGE 17 INDEPENDENT AUDITOR’S REPORT PAGE 18 5 2 SOUTH SYDNEY MEMBERS RUGBY LEAGUE FOOTBALL CLUB LIMITED MEMBER CO. SOUTH SYDNEY MEMBERS RUGBY LEAGUE FOOTBALL CLUB LIMITED MEMBER CO. SOUTH SYDNEY MEMBER CO. | | ANNUAL REPORT SOUTH SYDNEY MEMBER CO. | | ANNUAL REPORT FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 OCTOBER 2014 FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 OCTOBER 2014 • • CHAIRMAN’S REPORT 100 GRADE GAMES FOR SOUTH SYDNEY 1908-2014 Surname First Name Years 1st Grade games 2nd Grade games 3rd Grade games Total games Craig 'Tugger' 1980-92 208 47 42 297 For the first time in 43 years, our Club presents its Annual Report to Members as Rugby League Premiers.