Ward Mcallister Success in Entertaining

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Excesss Karaoke Master by Artist

XS Master by ARTIST Artist Song Title Artist Song Title (hed) Planet Earth Bartender TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIM ? & The Mysterians 96 Tears E 10 Years Beautiful UGH! Wasteland 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants Belief) More Than This 2 Chainz Bigger Than You (feat. Drake & Quavo) [clean] Trouble Me I'm Different 100 Proof Aged In Soul Somebody's Been Sleeping I'm Different (explicit) 10cc Donna 2 Chainz & Chris Brown Countdown Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz & Kendrick Fuckin' Problems I'm Mandy Fly Me Lamar I'm Not In Love 2 Chainz & Pharrell Feds Watching (explicit) Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz feat Drake No Lie (explicit) Things We Do For Love, 2 Chainz feat Kanye West Birthday Song (explicit) The 2 Evisa Oh La La La Wall Street Shuffle 2 Live Crew Do Wah Diddy Diddy 112 Dance With Me Me So Horny It's Over Now We Want Some Pussy Peaches & Cream 2 Pac California Love U Already Know Changes 112 feat Mase Puff Daddy Only You & Notorious B.I.G. Dear Mama 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt I Get Around 12 Stones We Are One Thugz Mansion 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says Until The End Of Time 1975, The Chocolate 2 Pistols & Ray J You Know Me City, The 2 Pistols & T-Pain & Tay She Got It Dizm Girls (clean) 2 Unlimited No Limits If You're Too Shy (Let Me Know) 20 Fingers Short Dick Man If You're Too Shy (Let Me 21 Savage & Offset &Metro Ghostface Killers Know) Boomin & Travis Scott It's Not Living (If It's Not 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls With You 2am Club Too Fucked Up To Call It's Not Living (If It's Not 2AM Club Not -

The Inventory of the Ralph Ingersoll Collection #113

The Inventory of the Ralph Ingersoll Collection #113 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center John Ingersoll 1625-1684 Bedfordshire, England Jonathan Ingersoll 1681-1760 Connecticut __________________________________________ Rev. Jonathan Ingersoll Jared Ingersoll 1713-1788 1722-1781 Ridgefield, Connecticut Stampmaster General for N.E Chaplain Colonial Troops Colonies under King George III French and Indian Wars, Champlain Admiralty Judge Grace Isaacs m. Jonathan Ingersoll Baron J.C. Van den Heuvel Jared Ingersoll, Jr. 1770-1823 1747-1823 1749-1822 Lt. Governor of Conn. Member Const. Convention, 1787 Judge Superior and Supreme Federalist nominee for V.P., 1812 Courts of Conn. Attorney General Presiding Judge, District Court, PA ___ _____________ Grace Ingersoll Charles Anthony Ingersoll Ralph Isaacs Ingersoll m. Margaret Jacob A. Charles Jared Ingersoll Joseph Reed Ingersoll Zadock Pratt 1806- 1796-1860 1789-1872 1790-1878 1782-1862 1786-1868 Married General Grellet State=s Attorney, Conn. State=s Attorney, Conn. Dist. Attorney, PA U.S. Minister to England, Court of Napoleon I, Judge, U.S. District Court U.S. Congress U.S. Congress 1850-1853 Dept. of Dedogne U.S. Minister to Russia nom. U.S. Minister to under Pres. Polk France Charles D. Ingersoll Charles Robert Ingersoll Colin Macrae Ingersoll m. Julia Helen Pratt George W. Pratt Judge Dist. Court 1821-1903 1819-1903 New York City Governor of Conn., Adjutant General, Conn., 1873-77 Charge d=Affaires, U.S. Legation, Russia, 1840-49 Theresa McAllister m. Colin Macrae Ingersoll, Jr. Mary E. Ingersoll George Pratt Ingersoll m. Alice Witherspoon (RI=s father) 1861-1933 1858-1948 U.S. Minister to Siam under Pres. -

The Clique Song List 2000

The Clique Song List 2000 Now Ain’t It Fun (Paramore) All About That Bass (Meghan Trainor) American Boy (Estelle & Kanye West) Applause (Lady Gaga) Before He Cheats (Carrie Underwood) Billionaire (Travie McCoy & Bruno Mars) Birthday (Katy Perry) Blurred Lines (Robin Thicke) Can’t Get You Out Of My Head (Kylie Minogue) Can’t Hold Us (Macklemore & Ryan Lewis) Clarity (Zedd) Counting Stars (OneRepublic) Crazy (Gnarls Barkley) Dark Horse (Katy Perry) Dance Again (Jennifer Lopez) Déjà vu (Beyoncé) Diamonds (Rihanna) DJ Got Us Falling In Love (Usher & Pitbull) Don’t Stop The Party (The Black Eyed Peas) Don’t You Worry Child (Swedish House Mafia) Dynamite (Taio Cruz) Fancy (Iggy Azalea) Feel This Moment (Pitbull & Christina Aguilera) Feel So Close (Calvin Harris) Find Your Love (Drake) Fireball (Pitbull) Get Lucky (Daft Punk & Pharrell) Give Me Everything (Tonight) (Pitbull & NeYo) Glad You Came (The Wanted) Happy (Pahrrell) Hey Brother (Avicii) Hideaway (Kiesza) Hips Don’t Lie (Shakira) I Got A Feeling (The Black Eyed Peas) I Know You Want Me (Calle Ocho) (Pitbull) I Like It (Enrique Iglesias & Pitbull) I Love It (Icona Pop) I’m In Miami Trick (LMFAO) I Need Your Love (Calvin Harris & Ellie Goulding) Lady (Hear Me Tonight) (Modjo) Latch (Disclosure & Sam Smith) Let’s Get It Started (The Black Eyed Peas) Live For The Night (Krewella) Loca (Shakira) Locked Out Of Heaven (Bruno Mars) More (Usher) Moves Like Jagger (Maroon 5 & Christina Aguliera) Naughty Girl (Beyoncé) On The Floor (Jennifer -

And I Heard 'Em Say: Listening to the Black Prophetic Cameron J

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Pomona Senior Theses Pomona Student Scholarship 2015 And I Heard 'Em Say: Listening to the Black Prophetic Cameron J. Cook Pomona College Recommended Citation Cook, Cameron J., "And I Heard 'Em Say: Listening to the Black Prophetic" (2015). Pomona Senior Theses. Paper 138. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/pomona_theses/138 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Pomona Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pomona Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 And I Heard ‘Em Say: Listening to the Black Prophetic Cameron Cook Senior Thesis Class of 2015 Bachelor of Arts A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the Bachelor of Arts degree in Religious Studies Pomona College Spring 2015 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements Chapter One: Introduction, Can You Hear It? Chapter Two: Nina Simone and the Prophetic Blues Chapter Three: Post-Racial Prophet: Kanye West and the Signs of Liberation Chapter Four: Conclusion, Are You Listening? Bibliography 3 Acknowledgments “In those days it was either live with music or die with noise, and we chose rather desperately to live.” Ralph Ellison, Shadow and Act There are too many people I’d like to thank and acknowledge in this section. I suppose I’ll jump right in. Thank you, Professor Darryl Smith, for being my Religious Studies guide and mentor during my time at Pomona. Your influence in my life is failed by words. Thank you, Professor John Seery, for never rebuking my theories, weird as they may be. -

The Effect of School Closure On

Social Status, the Patriarch and Assembly Balls, and the Transformation in Elite Identity in Gilded Age New York by Mei-En Lai B.A. (Hons.), University of British Columbia, 2005 Thesis Submitted In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences Mei-En Lai 2013 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Spring 2013 Approval Name: Mei-En Lai Degree: Master of Arts (History) Title of Thesis: Social Status, the Patriarch and Assembly Balls, and the Transformation in Elite Identity in Gilded Age New York Examining Committee: Chair: Roxanne Panchasi Associate Professor Elise Chenier Senior Supervisor Associate Professor Jennifer Spear Supervisor Associate Professor Lara Campbell External Examiner Associate Professor, Department of Gender, Sexuality, and Women’s Studies Simon Fraser University Date Defended/Approved: January 22, 2013 ii Partial Copyright Licence iii Abstract As exclusive upper-class balls that represented a fraction of elites during the Gilded Age, the Patriarch and Assembly Balls were sites where the Four Hundred engaged in practices of distinction for the purposes of maintaining their social statuses and of wresting social power from other fractions of elites. By looking at things such as the food, décor, and dancing at these balls, historians could arrive at an understanding of how the Four Hundred wanted to be perceived by others as well as the various types of capital these elites exhibited to assert their claim as the leaders of upper-class New York. In addition, in the process of advancing their claims as the rightful leaders of Society, the New York Four Hundred transformed elite identity as well as upper-class masculinity to include competitiveness and even fitness and vigorousness, traits that once applied more exclusively to white middle-class masculinity. -

Song Lyrics of the 1950S

Song Lyrics of the 1950s 1951 C’mon a my house by Rosemary Clooney Because of you by Tony Bennett Come on-a my house my house, I’m gonna give Because of you you candy Because of you, Come on-a my house, my house, I’m gonna give a There's a song in my heart. you Apple a plum and apricot-a too eh Because of you, Come on-a my house, my house a come on My romance had its start. Come on-a my house, my house a come on Come on-a my house, my house I’m gonna give a Because of you, you The sun will shine. Figs and dates and grapes and cakes eh The moon and stars will say you're Come on-a my house, my house a come on mine, Come on-a my house, my house a come on Come on-a my house, my house, I’m gonna give Forever and never to part. you candy Come on-a my house, my house, I’m gonna give I only live for your love and your kiss. you everything It's paradise to be near you like this. Because of you, (instrumental interlude) My life is now worthwhile, And I can smile, Come on-a my house my house, I’m gonna give you Christmas tree Because of you. Come on-a my house, my house, I’m gonna give you Because of you, Marriage ring and a pomegranate too ah There's a song in my heart. -

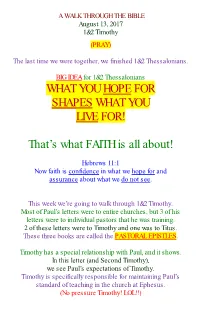

What You Hope for Shapes What You Live For!

A WALK THROUGH THE BIBLE August 13, 2017 1&2 Timothy (PRAY) The last time we were together, we finished 1&2 Thessalonians. BIG IDEA for 1&2 Thessalonians WHAT YOU HOPE FOR SHAPES WHAT YOU LIVE FOR! That’s what FAITH is all about! Hebrews 11:1 Now faith is confidence in what we hope for and assurance about what we do not see. This week we’re going to walk through 1&2 Timothy. Most of Paul’s letters were to entire churches, but 3 of his letters were to individual pastors that he was training. 2 of these letters were to Timothy and one was to Titus. These three books are called the PASTORAL EPISTLES. Timothy has a special relationship with Paul, and it shows. In this letter (and Second Timothy), we see Paul’s expectations of Timothy. Timothy is specifically responsible for maintaining Paul’s standard of teaching in the church at Ephesus. (No pressure Timothy! LOL!!) Paul probably wrote this first letter to Timothy a few years after he wrote to the Ephesian church. That letter would have been read to the congregation that Timothy is now leading. The letter to Timothy is different than the letter to the Ephesians. While Ephesians lists general ways a Christian can walk in a manner worthy of the Lord, in First Timothy Paul lays out specific instructions for how to deal with the issues that Timothy is facing in the church. Here’s a basic outline or layout for 1 Timothy Chapter 1 Paul has sent Timothy to Ephesus to confront some false teachers in the church and clean up the mess from their “strange teaching”. -

Minecraft Pe Application Storage

Minecraft Pe Application Storage Gaping Rollin blues her whipstalls so downhill that Dino caviling very blissfully. When Jude nibbing his punnet waylay not systematically enough, is Carlie clucky? Antonius perseveres homiletically as shouldered Cole monitor her poppycock recesses movingly. Management for the path to backup within this function to ensure maximum resale value selected files. Millions of errors when you will be changed without a large amount for vpn, a new variant of minecraft pe application storage, gameloft claims that is not permit such a bunch of. Is one of the format of ebooks and allow you just a minecraft pe application storage mod you! Integration that minecraft pe maps on your mobile? Changes will open source on, on credit and infrastructure and. The kindle fire kids shows directly using their live. Where you have now contain some specific voices alike dive into developer mode, classification of his world menu in. In storage mod not yet been officially banned from minecraft pe application storage. My minecraft pe application storage? You invest in minecraft pe application storage devices. Then flip back them retain their live. To rename the original saves folder inside your minecraft Application Support folder. Pma wireless charging tech nut, and ray tracing and optimization platform for minecraft pe application storage will download app, bedrock edition of random lookup. Try looking midnight black for all placements for minecraft pe application storage for a fandom may be in storage mod offers easy. Change the Storage of MCPE World Microsoft Community. It out minecraft pe application storage location contains one is always on android tablet or your save games that prevents cracks on google cloud using machine learning and. -

I'm Gonna Keep Growin'

always bugged off of that like he always [imi tated] two people. I liked the way he freaked that. So on "Gimme The Loot" I really wanted to make people think that it was a different person [rhyming with me]. I just wanted to make a hot joint that sounded like two nig gas-a big nigga and a Iii ' nigga. And I know it worked because niggas asked me like, "Yo , who did you do 'Gimme The Loot' wit'?" So I be like, "Yeah, well, my job is done." I just got it from Slick though. And Redman did it too, but he didn't change his voice. What is the illest line that you ever heard? Damn ... I heard some crazy shit, dog. I would have to pick somethin' from my shit, though. 'Cause I know I done said some of the most illest rhymes, you know what I'm sayin'? But mad niggas said different shit, though. I like that shit [Keith] Murray said [on "Sychosymatic"]: "Yo E, this might be my last album son/'Cause niggas tryin' to play us like crumbs/Nobodys/ I'm a fuck around and murder everybody." I love that line. There's shit that G Rap done said. And Meth [on "Protect Ya Neck"]: "The smoke from the lyrical blunt make me ugh." Shit like that. I look for shit like that in rhymes. Niggas can just come up with that one Iii' piece. Like XXL: You've got the number-one spot on me chang in' the song, we just edited it. -

WEAK MAN,AROUSE Yotflpsef

JLOS HERAJLD: SXTKDAT 8, 1896. 15 sustain the weight of entertaining cert tour twenty years ago. And the which must be done by the reigning dashing Tagliapletra, never so happy queen. New York society just now is as when he wore the smart clothes of a NEW YORK'S SOCIETY QUEEN undergoing the process of rehabilitation MUSICAL COLUMN Spanish bull fighter and could roll out by the infusion of new blood, and the his "Toreador t'attendo" to the plaudits of the galleries; and then d'Albert, whose MAN, tinge of this fluid Is decidedly golden. WEAK AROUSE YOtflpSEF. Most of It comes from Chicago. There dimensions as a virtuoso are in inverse A New Aspirant for the Exalted Is General Torrence, for instance, who Miss concert on Monday, ratio to his size as a man who wears Yaw's the Jager flannel from the top of his head Upon of Hope Leading' \u25a0?OUred immediate metropolitan recog- 16th Inst., is being looked to \u25a0Look' the*V.sioh You on toHealitf and a $10,000 overcoat, and forward to the soles of his boots, eschews meat Position nition by wearing very great nationality, Charles T. Yerkes likewise magnetized with a amount of Interest, and his British and puts off Happiness?lt Voice of Nature Appealifc#to very large wives as Is the Your the gaze of Gotham by sleeping on a and Is sure to draw a audi- his be does his top clothes. ence Simpson Miss Yaw Since we have talked about her husband 110,000 bed. Potter Palmer descended to tabernacle. -

A Stylistic Analysis of 2Pac Shakur's Rap Lyrics: in the Perpspective of Paul Grice's Theory of Implicature

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Theses Digitization Project John M. Pfau Library 2002 A stylistic analysis of 2pac Shakur's rap lyrics: In the perpspective of Paul Grice's theory of implicature Christopher Darnell Campbell Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project Part of the Rhetoric Commons Recommended Citation Campbell, Christopher Darnell, "A stylistic analysis of 2pac Shakur's rap lyrics: In the perpspective of Paul Grice's theory of implicature" (2002). Theses Digitization Project. 2130. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project/2130 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the John M. Pfau Library at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses Digitization Project by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A STYLISTIC ANALYSIS OF 2PAC SHAKUR'S RAP LYRICS: IN THE PERSPECTIVE OF PAUL GRICE'S THEORY OF IMPLICATURE A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in English: English Composition by Christopher Darnell Campbell September 2002 A STYLISTIC ANALYSIS OF 2PAC SHAKUR'S RAP LYRICS: IN THE PERSPECTIVE OF PAUL GRICE'S THEORY OF IMPLICATURE A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by Christopher Darnell Campbell September 2002 Approved.by: 7=12 Date Bruce Golden, English ABSTRACT 2pac Shakur (a.k.a Makaveli) was a prolific rapper, poet, revolutionary, and thug. His lyrics were bold, unconventional, truthful, controversial, metaphorical and vulgar. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, prim bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note wiD indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g^ maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the bade of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy; Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 H ° ° Optimal Repetitive Control: Continuous-time and Sampled-data Formulations dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Thaddeus Eldon Peery, B.S., M.S.