CARTOGRAPHY of PENNSYLVANIA BEFORE I 8Oo*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

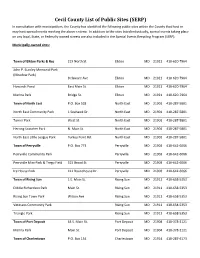

Cecil County List of Public Sites (SERP)

Cecil County List of Public Sites (SERP) In consultation with municipalities, the County has identified the following public sites within the County that host or may host special events meeting the above criteria. In addition to the sites listed individually, special events taking place on any local, State, or Federally-owned streets are also included in the Special Events Recycling Program (SERP). Municipally-owned sites: Town of Elkton Parks & Rec 219 North St. Elkton MD 21921 410-620-7964 John P. Stanley Memorial Park (Meadow Park) Delaware Ave. Elkton MD 21921 410-620-7964 Howards Pond East Main St. Elkton MD 21921 410-620-7964 Marina Park Bridge St. Elkton MD 21921 410-620-7964 Town of North East P.O. Box 528 North East MD 21901 410-287-5801 North East Community Park 1 Seahawk Dr. North East MD 21901 410-287-5801 Turner Park West St. North East MD 21901 410-287-5801 Herring Snatcher Park N. Main St. North East MD 21901 410-287-5801 North East Little League Park Turkey Point Rd. North East MD 21901 410-287-5801 Town of Perryville P.O. Box 773 Perryville MD 21903 410-642-6066 Perryville Community Park Perryville MD 21903 410-642-6066 Perryville Mini-Park & Trego Field 515 Broad St. Perryville MD 21903 410-642-6066 Ice House Park 411 Roundhouse Dr. Perryville MD 21903 410-642-6066 Town of Rising Sun 1 E. Main St. Rising Sun MD 21911 410-658-5353 Diddie Richardson Park Main St. Rising Sun MD 21911 410-658-5353 Rising Sun Town Park Wilson Ave. -

Flatlands Tour Ad

Baltimore Bicycling Club's 36th Annual Delaware-Maryland Flatlands Tour Dedicated to the memory of Dave Coder (7/6/1955 - 2/14/2004) Saturday, June 17, 2006 Event Coordinator: Ken Philhower (410-437-0309 or [email protected]) Place: Bohemia Manor High School, 2755 Augustine Herman Highway (Rt. 213), Chesapeake City, MD Directions: From Baltimore, take I-95 north to exit 109A (Rt. 279 south) and go 3 miles to Elkton. Turn left at Rt. 213 south. Cross Rt. 40 and continue 6 miles to Chesapeake City. Cross the C&D Canal Bridge and continue 1 mile. Turn right at traffic light (flashing yellow on weekends) into Bohemia Manor High School. Please allow at least 1-1/2 hours to get there from Baltimore. (It's about 65 miles.) From Annapolis, take US Route 50/301 east across the Bay Bridge and continue 10 miles. At the 50-301 split, continue straight on Rt. 301 north (toward Wilmington) for 32 miles. Turn left on Rt. 313 north and go 3 miles to Galena, then go straight at the traffic light onto Rt. 213 north. Continue on Rt. 213 north for 13 miles (about 2 miles past the light at Rt. 310), then turn left at the traffic light (flashing yellow on weekends) into Bohemia Manor High School. Please allow at least 1 hour and 45 minutes to get there from Annapolis. (It's about 70 miles.) From Washington DC, take Beltway Exit 19A, US Route 50 East, 20 miles to Annapolis, then follow Annapolis directions above. From Wilmington, DE, take I-95 south to exit 1A, Rt. -

Chapter 4 HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

Chapter 4 HISTORICAL BACKGROUND A. HISTORICAL OVERVIEW life are preserved within the family papers in the Library of Congress. Authored by later Rumseys, one William Rumsey dipped his pen in the ink and possibly by his grandson William, both manuscripts scratched the last line of an oversized compass rose on hold Charles immigrated to America at some point the upper right hand corner of the plat he was drawing. between 1665 and 1680 (Rumsey Family Papers, Box Rumsey paused. Even if he sanded the ink, it would 1, Folder 2). Conflicting at points but largely relat- have taken a little while for his work to dry. ing the same tale, these biographies state that Charles It was the height of summer and Rumsey’s House stood made his transatlantic journey in the company of on the edge of the buggy, humid marshes that fringed either a cousin or a brother and that the pair landed the Bohemia River on Maryland’s Eastern Shore. The first at either Charleston, South Carolina or Virginia house was grand and the view was beautiful but the where they remained for a number of years before conditions were so bad that William’s descendants setting out to seek their own fortunes. Most later pub- would eventually abandon the site because of “the lished biographical accounts of Charles Rumsey, e.g., prevalence of fever and ague in that locality.” Johnston 1881:508 and Scharf 1888:914, cite 1665 as the year of Mr. Rumsey’s New World disembarkation As Rumsey looked over his map (Figure 4.1), he and state unequivocally that Charleston was the site reviewed the carefully plotted outlines of the boundar- of his arrival. -

Dutch Trading Networks in Early North America, 1624-1750

COUNTRIES WITH BORDERS - MARKETS WITH OPPORTUNITIES: DUTCH TRADING NETWORKS IN EARLY NORTH AMERICA, 1624-1750 A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Kimberly Ronda Todt August 2012 © 2012 Kimberly Ronda Todt ii COUNTRIES WITH BORDERS – MARKETS WITH OPPORTUNITIES: DUTCH TRADING NETWORKS IN EARLY NORTH AMERICA, 1624-1750 Kimberly Ronda Todt, Ph. D. Cornell University 2012 Examining the Dutch in early America only through the prism of New Netherland is too limiting. The historiography inevitably follows a trajectory that leads to English takeover. This work explores how Dutch merchants fostered and nurtured trade with early American colonies at all levels and stages – from ship owners to supercargos to financiers – and over the varied geographical and political terrains in which early American commodities were grown, hunted, harvested, and traded. Chapters are organized geographically and chronologically and survey how Dutch trading networks played out in each of early America’s three major regions – New England, the Middle Colonies, and the Chesapeake and later the Lower South from 1624 through 1750. Chronicling Dutch trade also serves to emphasize that participants in early America were rooted in global – as well as in local, regional, and imperial – landscapes. Accordingly, while each of the chapters of this work is regional, they are also integrated into something larger. In the end, this is a study that thinks across the Atlantic world yet explores various commodities or individual merchants to understand markets and networks. This narrative also demonstrates how profoundly Dutch capital, merchants, and iii goods affected early America. -

Storefront Retail for Sale

for sale storefront retail Baltimore County, MD 35 augustine herman highway | elkton, maryland 21921 building size 9,639 sf lot size 1.078 Acres 9,639 SF ON 1.078 AC zoning C-2 (Highway Commercial) year built 2010 traffic count 17,880 AADT (Rt. 213) sale price $1,700,000 Highlights ► Class B strip retail building with great visibility on Rt. 213 ► Prime location in the heart of Elkton’s commercial district ► Available as an investment or end user building ► 224 ft. of frontage on Augustine Herman Hwy (17,880 cars/day) ► Great opportunity to invest in Elkton’s growing retail market Street View Tom Mottley | Senior Vice President Tom Fidler | Executive Vice President & Principal 443.573.3217 [email protected] 410.494.4860 [email protected] MacKenzie Commercial Real Estate Services, LLC • 410-821-8585 • 2328 W. Joppa Road, Suite 200 | Lutherville-Timonium, Maryland 21093 • www.MACKENZIECOMMERCIAL.com for sale aerial Baltimore County, MD 35 augustine herman highway | elkton, maryland 21921 213 AUGUSTINE HERMAN HWY 9,639 SF 17,880 AADT ON 1.078 AC NORMAN ALLEN ST 213 N Tom Mottley | Senior Vice President Tom Fidler | Executive Vice President & Principal 443.573.3217 [email protected] 410.494.4860 [email protected] MacKenzie Commercial Real Estate Services, LLC • 410-821-8585 • 2328 W. Joppa Road, Suite 200 | Lutherville-Timonium, Maryland 21093 • www.MACKENZIECOMMERCIAL.com for sale trade area Baltimore County, MD 35 augustine herman highway | elkton, maryland 21921 279 213 268 BOOTH -

Evert Pels, of Rensselaerswyck, Erected This House in 1656, Shortly After the Heere Dwars Straet (Now Exchange Place) Was Cut Through

Evert Pels, of Rensselaerswyck, erected this house in 1656, shortly after the Heere Dwars Straet (now Exchange Place) was cut through. It stood on the north-east corner of Exchange Place and Broadway. Augustine Herrman bought the house and garden in October of this year.—Liber Deeds, A: 76. When he conveyed it to Hendrick Hendricksen Kip, the younger, in 1662, he extended his fence through to the Graft, a mistake not rectified until 1668.—Liber Deeds, B: 147; cf. Deeds fc? Conveyances (etc.), 1659-1664, trans, by O'Callaghan, 272-3. Augustine Herrman (Augustyn Heermans, Hermans, Heermansz) was a native of Prague, in Bohemia, and was born about 1608. He served in the army of Wallenstein in the Thirty Years War, and is said to have taken part in the battle of Lutzen, in 1632, when Wallenstein was defeated by the Swedes under Gustavus Adolphus. Herrman's voyage to America was undertaken as agent or factor for the large commercial house of Peter Gabry & Sons, of Amsterdam; he sailed on the "Maecht van Enkhuysen" (Maid of Enkhuizen), and arrived in 1633. He had become the largest and most prosperous merchant of the town by 1650, when he had erected his great warehouse on the Strand. He dealt extensively in furs, tobacco, wines, groceries, dry-goods, and negro slaves. He was also a banker and a lawyer. That he was a linguist, and spoke French, Dutch, German, and English, is well known; he was also a land surveyor, and was not without merit as an artist. A man of vivid imagination, strong personality, and many parts, he easily towers a head and shoulders above the community of petty burghers in which he found himself after coming to New Amsterdam.—Jameson's Nar. -

Governor Andrew M. Cuomo to Proclaim MEMORIALIZING October

Senate Resolution No. 1006 BY: Senator MARTUCCI MEMORIALIZING Governor Andrew M. Cuomo to proclaim October 2021, as Czech-American Heritage Month in the State of New York WHEREAS, It is the custom of this Legislative Body to recognize and pay just tribute to the cultural heritage of the ethnic groups which comprise and contribute to the richness and diversity of the community of the State of New York; and WHEREAS, Attendant to such concern, and in keeping with its time-honored traditions, it is the sense of this Legislative Body to memorialize Governor Andrew M. Cuomo to proclaim October 2021, as Czech-American Heritage Month in the State of New York; and WHEREAS, Augustine Herman was the first documented Czech (Bohemian) settler in North America; while working for the West India Company, he came to New Amsterdam, now known as New York; and WHEREAS, A man of many talents, Augustine Herman became one of the most influential people in the Dutch Province which led to his appointment to the Council of Nine to advise the New Amsterdam Governor Peter Stuyvesant; one of his greatest achievements was his celebrated map of Maryland and Virginia commissioned by Lord Baltimore; and WHEREAS, There was another Bohemian living in New Amsterdam at that time, Frederick Philipse, who became equally famous; he was a successful merchant who, eventually, became the wealthiest person in the entire Dutch Province; and WHEREAS, In 1735, the first significant wave of Czech colonists, the Moravian Brethren, began arriving on the American shores; they were the -

DFNJ 2016 Edition 7-17-16 OGDEN.Pdf

FOUNDERS OF NEW JERSEY First Settlements, Colonists and Biographies by Descendants Dr. Evelyn Hunt Ogden Registrar General The Descendants of Founders of New Jersey Third Edition 2016 First Settlements, Colonists and Biographies by Descendants, Third Edition 2016 This 250+ page E-book contains sketches of the earliest English settlements, 137 biographies of founders of New Jersey the state, and an extensive index of over 1,800 additional early colonists associated with events and settlement during the Proprietary Period of New Jersey. Founders of New Jersey: First Settlements, Colonists and Biographies by Descendants Member Authors Paul Woolman Adams, Jr. Steven Guy Brandon Rowley Mary Ellen Ezzell Ahlstrom Craig Hamilton Helen L. Schanck Annie Looper Alien William Hampton Deanna May Scherrer Reba Baglio Robert J. Hardie, Sr. Marjorie Barber Schuster Lucy Hazen Barnes James Paul Hess Judy Scovronsky Michael T. Bates Steve Hollands Sara Frasier Sellgren Kathryn Marie Marten Beck Mary Jamia Case Jacobsen James A Shepherd Taylor Marie Beck Edsall Riley Johnston, Jr. Barbara Carver Smith Patricia W. Blakely Elaine E. Johnston Marian L. Smith Matthew Bowdish John Edward Lary Jr Martha Sullivan Smith Margaret A. Brann Guy Franklin Leighton Myron Crenshaw Smith Clifton Rowland Brooks, M.D. Marian L. LoPresti George E. Spaulding, Jr. Richard Charles Budd Constan Trimmer Lucy Heather Elizabeth Welty Speas Daniel Byram Bush Michael Sayre Maiden, Jr. Charlotte Van Horn Squarcy James Reed Campbell Jr Donna Lee Wilkenson Malek Earl Gorden Stannard III Esther Burdge Capestro Douglas W. McFarlane Marshall Jacqueline Frank Strickland Michael Charles Alan Russell Matlack David Strungfellow Warren R. Clayton Amy Adele Matlack Harriet Stryker-Rodda Eva Lomerson Collins Nancy Elise Matlack Kenn Stryker-Rodda Mirabah L. -

Maryland Historical Magazine, 1938, Volume 33, Issue No. 4

Vol. XXXIII DECEMBER, 1938 No. 4 MARYLAND HISTORICAL MAGAZINE <b AJ PUBLISHED BY THE MARYLAND fflSTORICAL SOCIETY ISSUED QUARTERLY ANNUAL SUBSCRIPTION,$aOO-SINGLE NUMBEBS, 75CT*, BALTIMORE Entered as Second-Claaa Matter, April 24, 1917, at the Postoffice, at Baltimore, Maryland, under the Act of August 21, 1012. THE MARYLAND HISTORICAL SOCIETY INCORPORATED 1843. H. IRVINE KETSEB MEMORIAL BCILDINQ, 201 W. MONUMENT STREET, BALTIMORE OFFICERS. Yice-President {Acting President), GEORGE L. KADCLIFEB, Y ice-Presidents J. HALL PLEASANTS, SAMUEL K. DENNIS. Corresponding Secretary, Recording Secretary, WILLIAM B. MARYE. JAMES E. HANCOCK. Treasurer, HEYWARD E. BOYCE. THE COUNCIL. THE GENEBAL OFEICERS < AND REPRESENTATIVES OF STANDING COMMITTEES: G. CORNER FENHAGEN, Representing the Trustees of the Athenaeum. W. STULL HOLT, " Committee on Publication. L. H. DIELMAN, " Committee on the Library. WILLIAM INGLE, " Committee on Finance. MRS. ROBERT F. BRENT, " Committee on Membership. LAURENCE H. FOWLER, " Committee on the Gallery. DOUGLAS H. GORDON, « Committee on Addresses. CLINTON LEVERING RIGGS, 1806-1938 President, Maryland Historical Society 1935-1938 /»54 SC 58%l~l~/3^ MARYLAND HISTORICAL MAGAZINE VOL. XXXIII. DECEMBER, 1938. No. 4. Clinton letoting Biggjs General Clinton Levering Riggs, the President of the Mary- land Historical Society, died suddenly on Sunday night, Sep- tember 11, 1938, in the Union Memorial Hospital from heart disease, in the 73rd year of his age. He was buried from his home in Baltimore on Tuesday, September thirteenth. Although he was born in New York, September 13, 1866, his family for many generations, dating back to the seventeenth century, had been identified with Maryland public and social life. His father was Lawrason Kiggs, and his mother before her marriage was Mary Turpin Bright, the daughter of Senator Jesse Bright of Indiana. -

4 the Cultural Contexts of the Wilson Farm Tenancy Site

AT THE ROAD’S EDGE: FINAL ARCHAEOLOGICAL INVESTIGATIONS OF THE WILSON FARM TENANCY SITE 4 The Cultural Contexts of the Wilson Farm Tenancy Site On July 24, 1608, Captain John Smith sailed away from Jamestown with a company of 12 men on his second exploratory expedition to Chesapeake Bay. Their shallop, the Phoenix, was an open barge, probably about 30 feet long and 8 feet wide. With a draft of less than 2 feet of water and a capacity of nearly 3 tons, it was ideally suited to coastal exploration. It could sail in deep or shallow water, propelled by sail or oars, and was light enough to pull ashore. On July 29, Smith and his crew reached the mouth of the Patapsco River, the most northern extent of his earlier expedition. Half his men had become too ill to take their turn at the oars. This situation precluded the exploration of smaller tributaries because sail power was only useful for large rivers (National Park Service 2011; Salmon 2006:21). The following day, the Phoenix arrived at Turkey Point in Cecil County, Maryland, where the bay divided into four main rivers: the Susquehanna, the North East, the Elk, and the Sassafras. Several crewmen walked 6 miles up Little North East Creek, where they placed a wooden cross to claim the head of the bay for England. Smith explored the rivers during the next week. He visited the palisaded town of Tockwogh on the Sassafras River, where Susquehannock Indians of southern Lancaster County had arrived to participate in a trading party, along with dancing and feasting. -

CE-1061 Boulden-Dawkins Farm, (Brick House Farm)

CE-1061 Boulden-Dawkins Farm, (Brick House Farm) Architectural Survey File This is the architectural survey file for this MIHP record. The survey file is organized reverse- chronological (that is, with the latest material on top). It contains all MIHP inventory forms, National Register nomination forms, determinations of eligibility (DOE) forms, and accompanying documentation such as photographs and maps. Users should be aware that additional undigitized material about this property may be found in on-site architectural reports, copies of HABS/HAER or other documentation, drawings, and the “vertical files” at the MHT Library in Crownsville. The vertical files may include newspaper clippings, field notes, draft versions of forms and architectural reports, photographs, maps, and drawings. Researchers who need a thorough understanding of this property should plan to visit the MHT Library as part of their research project; look at the MHT web site (mht.maryland.gov) for details about how to make an appointment. All material is property of the Maryland Historical Trust. Last Updated: 03-06-2018 MARYLAND HISTORICAL TRUST NR Eligible: yes_ DETERMINATION OF ELIGIBILITY FORM no roperty Name: Boulden-Dawkins Farm Inventory Number: CE-1061 Address: 1679 Augustine Herman Highway City: Chesapeake City Zip Code: 21001 County: Cecil USGS Topographic Map: ------------------Elkton Owner: J.R. Crouse Holdings LLC Is the property being evaluated a district? no Tax Parcel Number: _6_15__ Tax Map Number: _3_8 ___Tax Account ID Number: _0_2-_0_3_9_6_8_0 ____________ -

To Cecil County Maryland!

Welcome to Cecil County Maryland! CENTRALLY located between Philadelphia and Baltimore on I-95, our vibrant towns, waterways, foodie destinations, and scenic countryside provide the perfect escape. Experience shopping, events, horses, and waterfront fun! Escape to Cecil County . Just a Daydream Away! Escape to Cecil County! CHARLESTOWN Market Street Café — 315 Market St., Charlestown; 410-287-6374; marketstreetcafemd.com Wellwood River Shack — 121 Frederick St., Charlestown; 410-287- 6666; wellwoodcrabs.com; BD, S The Wellwood — 523 Water St., Charlestown; 410-287-6666; wellwoodclub.com; BD, WV CHESAPEAKE CITY Bayard House — 11 Bohemia Ave, aerial: Andrew Muff Chesapeake City; 410-885-5040; bayardhouse.com; WF TABLE OF CONTENTS FOODIE Chesapeake Inn & Marina — 605 DESTINATIONS 2nd St, Chesapeake City; 410-885- Foodie Destinations 2 2040; chesapeakeinn.com; BD, WF Restaurants, Wineries, Jo Jo’s Diner — 2535 Augustine Restaurants (2) Wineries (4) Breweries (5) Sweet Treats, Coffee (5) Breweries, Sweet Treats, Herman Hwy, Chesapeake City; 410- and Coffee Things to Do 6 885-5066; jojodiner.net DESTINATION KEY Catch the Action (6) Outdoor Recreation (6) Water Activities (7) Maria’s Italian Restaurant — Family & Farm Fun (7) History (8) The Arts (9) BD = Boat Docks 2525 Augustine Herman Hwy, S = Seasonal Chesapeake City; 410-885-5577; Event Highlights 8 WF = Waterfront mariaspizzamd.com Specialty Shops 12 WV = Water View Prime 225 — 225 Bohemia Ave, Chesapeake City; 410-885-7009; Wedding & Event Venues 13 prime225.com Places to Stay 14 Schaefer’s Canal House — 208 B&Bs / Hotels / Campgrounds / RV Resort Restaurants Bank St; Chesapeake City; 410-885- 7200; schaeferscanalhouse.com; CECILTON Marinas & More 16 BD, WF Cecilton Pizzeria — 110 W.