The Doll Project As a Liberatory Art Intervention for Conscious Raising And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Plan for Transformation: How a Plan with Lofty Goals Has Underperformed and Forever Changed Public Housing in Chicago

Public Interest Law Reporter Volume 24 Issue 1 Article 13 2018 The Plan for Transformation: How a plan with lofty goals has underperformed and forever changed public housing in Chicago Kenya Barbara Follow this and additional works at: https://lawecommons.luc.edu/pilr Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Criminal Procedure Commons, Environmental Law Commons, and the Human Rights Law Commons Recommended Citation Kenya Barbara, The Plan for Transformation: How a plan with lofty goals has underperformed and forever changed public housing in Chicago, 24 Pub. Interest L. Rptr. 101 (2018). Available at: https://lawecommons.luc.edu/pilr/vol24/iss1/13 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by LAW eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Public Interest Law Reporter by an authorized editor of LAW eCommons. For more information, please contact law- [email protected]. Barbara: The Plan for Transformation: How a plan with lofty goals has unde No. 1 * Fall 2018 The Plan for Transformation: How a plan with lofty goals has underperformed and forever changed public housing in Chicago Kenya Barbara Chicago Housing Authority (CHA) is the third largest public housing agency in America.' It was founded in 1937 for the purpose of owning and operating public housing that was built through President Roosevelt's Public Works Administration.2 What began as transitional housing for World War II veterans and their families eventually became many different public housing developments all over the city. At one point, CHA was the biggest landlord in Chicago with over 40,000 units of housing.3 With these high numbers, came a high number of problems. -

The Chicago Housing Authority 10

the ,~ i J. Popkin,Victoria E. Gwiasda,Lynn M. Olson,[_) inis P. Rosenbaum,and LarryBuron FOREWORD BY REBECCA M. BLANK J The Hidden War 1£4/-7~ The Hidden War Crime and the Tragedy of Public Housing in Chicago SUSAN J. POPKIN VICTORIA E. GWIASDA LYNN M. OLSON DENNIS P. ROSENBAUM LARRY BURON .-- IPF~QRERYY ©f~ ~ation~l @iminal Justics Roi~o~c~ 8onii@ (t~¢jR8) Box 6000 Rockville, ~E) 20849o6000 RUTGERS UNIVERSITY PRESS New Brunswick, New Jersey, and London Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The hidden war : crime and the tragedy of public housing in Chicago / Susan J. Popkin... let al.]. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8135-2832-1 (cloth : alk. paper) -- ISBN 0-8135-2833-X (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Chicago Housing Authority. 2. Housing authorities--Illinois-- Chicago. 3. Public housing--Illinois--Chicago. I. Popkin, Susan J. HD7288.78.U52 C44 2000 363.5'85'0977311--dc21 99-056789 British Cataloging-in-Publication data for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2000 by Susan J. Popkin All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher. Please contact Rutgers University Press, 100 Joyce Kilmer Avenue, Piscataway, NJ 08854-8099. The only exception to this prohibition is "fair use" as defined by U.S. copyright law. Manufactured in the United States of America - Contents LIST OF PHOTOS, FIGURES, AND TABLES VII FOREWORD BY REBECCA M. -

I the UNIVERSITY of CHICAGO PRIVATIZING CHICAGO: the POLITICS of URBAN REDEVELOPMENT in PUBLIC HOUSING REFORMS a DISSERTATION SU

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRIVATIZING CHICAGO: THE POLITICS OF URBAN REDEVELOPMENT IN PUBLIC HOUSING REFORMS A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SERVICE ADMINISTRATION IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY BY AMY TURNBULL KHARE CHICAGO, ILLINOIS JUNE 2016 i TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES .................................................................................................................vii LIST OF FIGURES ...............................................................................................................viii LIST OF MAPS .....................................................................................................................ix ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ...................................................................................................x ABSTRACT ...........................................................................................................................xviii CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................1 Problem Statement .................................................................................................................1 Theoretical Overview.............................................................................................................3 Research Goals.......................................................................................................................7 Dissertation Overview ...........................................................................................................8 -

Chicago Housing Authority

SCATTERED SITES NORTH CENTRAL ALTGELD GARDENS SENIOR HOUSING SOUTH SCATTERED SITES NORTH EAST BRIDGEPORT HOMES SENIOR HOUSING NORTH SCATTERED SITES SOUTH WEST DEARBORN HOMES SENIOR HOUSING CENTRAL SCATTERED SITES WEST SCATTERED SITES SOUTH EAST ICKES HOMES LATHROP HOMES LAWNDALE GARDENS LECLAIRE COURTS EXTENSION LOWDEN HOMES PHILLIP MURRAY HOMES RANDOLPH TOWERS TRUMBULL PARK HOMES WENTWORTH GARDENS LEGENDS SOUTH GRACE ABBOTT HOMES ROBERT H. BROOKS HOMES AND EXTENSION JANE ADDAMS HOMES FRANCIS CABRINI HOMES AND EXTENSIONS WILLIAM GREEN HOMES HENRY HORNER HOMES LAKE MICHIGAN HOMES MADDEN PARK HOMES IDA B. WELLS HOMES AND EXTENSION CLARENCE DARROW HOMES ROBERT TAYLOR HOMES ROCKWELL GARDENS STATEWAY GARDENS WASHINGTON PARK HOMES ROOSEVELT SQUARE DOMAIN LOFTS OLD TOWN VILLAGE EAST RIVER VILLAGE OLD TOWN VILLAGE WEST ORCHARD PARK MOHAWK NORTH RENAISSANCE NORTH MOHAWK INFILL OLD TOWN SQUARE CENTRUM I VILLAGE NORTH RAYMOND M. HILLIARD CENTER WESTHAVEN PARK LAKEFRONT REPLACEMENT HOUSING LAKE PARK CRESCENT HUTCHINSON’S ROW JAZZ ON THE BOULEVARD OAKWOOD SHORES THE LANGSTON QUINCY HOMES MOUNT VERNON ARCHER COURTS THE PERSHING PARK BOULEVARD ST. EDMUND’S MEADOWS PRAIRIE COURTS EXTENSION SOUTH PARK PLAZA DO YOU HAVE A VISION FOR CHANGE? SCATTERED SITES NORTH CENTRAL ALTGELD GARDENS SENIOR HOUSING SOUTH SCATTERED SITES NORTH EAST BRIDGEPORT HOMES SENIOR HOUSING NORTH SCATTERED SITES SOUTH WEST DEABORN HOMES SENIOR HOUSING CENTRAL SCATTERED SITES WEST SCATTERED SITES SOUTH EAST HAROLD ICKES HOMES LATHROP HOMES LAWNDALE GARDENS LECLAIRE COURTS EXTENSION LOWDEN HOMES PHILLIP MURRAY HOMES RANDOLPH TOWERS TRUMBULL PARK HOMES WENTWORTH GARDENS LEGENDS SOUTH GRACE ABBOTT HOMES ROBERT H. BROOKS HOMES AND EXTENSION JANE ADDAMS HOMES FRANCIS CABRINI HOMES AND EXTENSIONS WILLIAM GREEN HOMES HENRY HORNER HOMES LAKE MICHIGAN HOMES MADDEN PARK HOMES IDA B. -

![HOUSING OUTLINE] This Outline Was Created for the Poverty and Housing Law Seminar at the University of Chicago Law School](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0649/housing-outline-this-outline-was-created-for-the-poverty-and-housing-law-seminar-at-the-university-of-chicago-law-school-2880649.webp)

HOUSING OUTLINE] This Outline Was Created for the Poverty and Housing Law Seminar at the University of Chicago Law School

LAF Revised: January 1, 2016 Lawrence Wood Director of the Housing Practice Group 1 [HOUSING OUTLINE] This outline was created for the Poverty and Housing Law seminar at the University of Chicago Law School. It was drafted by Lawrence Wood, Lecturer in Law. I. LAF. ........................................................................................................................................................ 13 A. Overview. ................................................................................................................................................ 13 B. LSC Rules and Restrictions. .................................................................................................................. 13 C. Practice Groups. ..................................................................................................................................... 15 D. Task Forces. ............................................................................................................................................ 15 E. Housing Practice Group. ....................................................................................................................... 16 F. Client Screening Unit. ........................................................................................................................... 17 G. Legal Server. ........................................................................................................................................... 18 H. Interviewing Clients. ............................................................................................................................. -

FY2010 Moving to Work Annual Plan

FY2010 Moving to Work Annual Plan Plan for Transformation Year 11 October 22, 2009 BOARD OF COMMISSIONERS Martin Nesbitt, Chair Hallie Amey Deverra Beverly Dr. Mildred Harris Michael Ivers Myra King Carlos Ponce M. Bridget Reidy Sandra Young EXECUTIVE STAFF Lewis A. Jordan, President/Chief Executive Officer Kris Warren, Chief Operating Officer Scott W. Ammarell, General Counsel Elias Rosario, Chief Financial Officer Linda J. Kaiser, Executive Vice-President, Resident Services William Little, Executive Vice-President, Development Adrienne Minley, Executive Vice-President, Liaison to the Mayor’s Office Pamela Mitchell-Boyd, Executive Vice-President, Board of Commissioners Addie Wright, Executive Vice-President, Organizational Effectiveness Charles Hillman, Senior Vice-President, Asset Management - Family Portfolio Bryan Land, Senior Vice-President, Information Technology Services Jessica Porter, Senior Vice-President, Asset Management - Housing Choice Voucher Program Timothy Veenstra, Senior Vice-President, Asset Management - Mixed-Income Portfolio Photography by Eric Werner Message from the President/Chief Executive Officer It is with great pleasure I present the FY2010 Moving To Work (MTW) Annual Plan. For the Chicago Housing Authority (CHA), the previous fiscal year was monumental and reflective. In FY2009, CHA reached the 10-year milestone of the Plan for Transformation (the Plan), received a boost in funding through the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, and witnessed positive results in the first year implementation of new policies outlined in the Amended and Restated MTW Agreement. These are only a few activities that established the momentum we seek to build upon in Year 11 of the Plan. CHA has streamlined its planning and reporting processes in the FY2010 MTW Annual Plan to adhere to new guidelines and directly highlight activities that increase housing choices for low-income families, encourage families on their path to self-sufficiency and enhance cost effectiveness in federal expenditures. -

Race, Segregation and the Chicago Housing Authority David T

The College of Wooster Libraries Open Works Senior Independent Study Theses 2013 Chicago's Wall: Race, Segregation and the Chicago Housing Authority David T. Greetham The College of Wooster, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://openworks.wooster.edu/independentstudy Part of the African American Studies Commons, and the Urban Studies Commons Recommended Citation Greetham, David T., "Chicago's Wall: Race, Segregation and the Chicago Housing Authority" (2013). Senior Independent Study Theses. Paper 3801. https://openworks.wooster.edu/independentstudy/3801 This Senior Independent Study Thesis Exemplar is brought to you by Open Works, a service of The oC llege of Wooster Libraries. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Independent Study Theses by an authorized administrator of Open Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Copyright 2013 David T. Greetham The College of Wooster Chicago’s Wall: Race, Segregation and the Chicago Housing Authority by David Greetham Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of Senior Independent Study Supervised by Jeff Roche Department of History Spring 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements i List of Figures ii Introduction 1 Chapter One: Contestation, Expansion and Confinement: A History of Chicago 8 Chapter Two: Political Hijacking: The 1949-1950 Site Selection Controversy 34 Chapter Three: Trumbull Park: The Collapse of the Chicago Housing Authority 65 Chapter Four: A Pyrrhic Victory: Gautreaux v. Chicago Housing Authority 86 Conclusion 124 Annotated Bibliography 130 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would not have been able to complete this work without the help of my advisor Jeff Roche. Throughout the process, Professor Roche helped me narrow my interests, provided thoughtful questions and responses, and always was ready to suggest ways to make my thesis better. -

Public Housing in Chicago, USA

Public Housing in Chicago, USA A Focus on Problems and Solutions in Design, Pattern and Practice Growth & Structure of Cities Program Bryn Mawr College Haverford College Charlie Rubin Fall 2007 Abstract Ever since the housing shortage in the early part of the 20th century, the United States has faced challenges in providing homes for all of its citizens. Throughout the 1940’s and early 1950’s local housing authorities scrambled to create a prototype for the perfect Public Housing plan. Due to economic and political pressures, most of the designs were finalized as vertical skyscrapers placed in the outskirts of a city, or in an already dilapidated area. Years later we can see that a large part of these projects have become crime-ridden, decrepit, and stigmatized as areas of danger and distaste. Many scholars attribute the architecture and design of these projects for their failure. My paper will examine the validity of this idea and provide evidence for how the architecture and design played only a minor part in the downfall of these projects. Other factors include the basic lack of funding for maintenance of the buildings, the economic climate of the times, the homogeneity of the residents, and most importantly, almost no social outlets for the youth of these projects. To prove these causes, I have analyzed the life, death, and rebirth of two Public Housing projects in Chicago built during the 1950s. One might argue abstractly about the fundamental deficiencies of the tower-in-the-park as a form [of] urban housing and urban design: the lack of public space and street life; the lack of connection between mothers in the tower and children playing fifteen floors below; the inhuman scale and isolation from the fabric of the city that this design produced. -

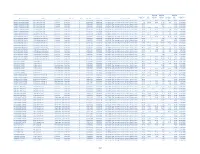

Property Name Address City County State ZIP Code Latitude

Building Building Dwelling Inspection Site Exterior System Common Unit Inspection Property name Address City County State ZIP code Latitude Longitude Housing Authority Score Score Score Score Area Score Score Date SAMUEL GOMPERS HOMES 450 N 6th St Apt 13G E St Louis Saint Clair IL 622011326 38.629108 -90.151692 The Housing Authority of City of East St. Louis 78.37 0 94.77 100 48.52 88.72 5/16/2000 SAMUEL GOMPERS HOMES 450 N 6th St Apt 13G E St Louis Saint Clair IL 622011326 38.629108 -90.151692 The Housing Authority of City of East St. Louis 53 22.18 43.68 97.52 74.6 57.97 6/15/2001 SAMUEL GOMPERS HOMES 450 N 6th St Apt 13G E St Louis Saint Clair IL 622011326 38.629108 -90.151692 The Housing Authority of City of East St. Louis 56.77 98.51 33.99 5/23/2002 SAMUEL GOMPERS HOMES 450 N 6th St Apt 13G E St Louis Saint Clair IL 622011326 38.629108 -90.151692 The Housing Authority of City of East St. Louis 54.44 99.5 41.92 3/31/2003 SAMUEL GOMPERS HOMES 450 N 6th St Apt 13G E St Louis Saint Clair IL 622011326 38.629108 -90.151692 The Housing Authority of City of East St. Louis 55.74 25.75 72.93 100 66.25 44.89 6/25/2004 SAMUEL GOMPERS HOMES 450 N 6th St Apt 13G E St Louis Saint Clair IL 622011326 38.629108 -90.151692 The Housing Authority of City of East St. -

An Examination of the Social and Physical Environment of Public

AAnn EExxaammiinnaattiioonn ooff tthhee SSoocciiaall aanndd PPhhyyssiiccaall EEnnvviirroonnmmeenntt ooff PPuubblliicc HHoouussiinngg RReessiiddeennttss iinn TTwwoo CChhiiccaaggoo DDeevveellooppmmeennttss iinn TTrraannssiittiioonn Caterina G. Roman Carly Knight THE URBAN INSTITUTE Washington, DC MAY 2010 Acknowledgments The authors would like to thank the many people who are collaborating to bring the Chicago Family Case Management Demonstration to life. We thank the dedicated staff of Heartland Human Care Services and Housing Choice Partners for their careful and compassionate work. We are grateful for the support of the Chicago Housing Authority, which has been a genuine partner in designing, funding, and advancing both the service model and the research evaluation for the demonstration. And our thanks to the residents of Wells/ Madden Park and Dearborn Homes for their willingness to take part both in the new services and the research. We would also like to thank the funders who are supporting the Demonstration: the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Annie E. Casey Foundation, the John D. Rockefeller Foundation, the Partnership for New Communities, and JPMorgan Chase. Their vision has supported what we hope is a new model of services for distressed public housing residents. Finally, for this report, we would like to thank Susan Popkin, Brett Theodos, Liza Getsinger and Joe Parilla who are part of the research team at the Urban Institute. We are also grateful to our reviewers for their thoughtful comments. About the Authors Caterina Roman is an assistant professor in the Department of Criminal Justice at Temple University. Prior to joining Temple University in 2008, Dr. Roman had been a senior research associate at the Urban Institute. -

The Chicago Housing Authority Mtw Annual

THE CHICAGO HOUSING AUTHORITY MTW ANNUAL REPORT FY2001 FAMILY DEVELOPMENTS SENIOR DEVELOPMENTS ABLA Homes 150 S. Campbell Lincoln & Sheffield Annex Altgeld Gardens/Murray Homes 4227 S. Oakenwald Lincoln Perry Annex Bridgeport Homes 4250 S. Princeton Lincoln Perry Apts. Cabrini Extension North 49th & Langley Apts. Loyola &Ridge Apts. Cabrini Green 64th & Yates Apts. Parkside Apts. Dearborn Homes 69th & South Chicago Parkview Harrison Courts 91st & South Chicago Pomeroy Apts. Hearts United I and II Albany Racine Harold Ickes Homes Armour Square Annex Schneider Apts. Henry Horner Homes Armour Square Apts. Sheridan & Leland Hilliard Homes Bridgeport Elderly Sheridon & Devon Jazz on the Boulevard Britton/Budd Apts. Shields Lake Crescent Callner Sullivan Lake Parc Place Campbell Apts. Washington Park Lakefront Replacement Housing Castleman Apts. Wicker Annex Lakefront Scattered Sites Clark & Irving Annex Wicker Park Lathrop Courts Clark & Irving Apts. Wm. Jones Lawndale Gardens Clark & Webster Apts. LeClaire Courts Dickens & Burling Loomis Courts Eckhart Lowden Homes Eckhart Annex Maplewood Courts Fisher Apts. Mohawk North Flannery Apts. North Town Village Franklin/Drake Ogden Courts Garfield Old Town Square; Old Town East; Old Town West Green Apts. Orchard Park Hilliard Senior Prairie Courts Judge Slater Annex Randolph Towers Judge Slater Apts. Renaissance North Kenmore Apts. Rockwell Gardens Larrabee Senior Apts. St. Edmunds Meadows LaSalle/Division Stateway Gardens Lathrop Elderly Robert Taylor Homes Lawrence Apts. Trumbull Park Homes Lincoln & Sheffield Washington Park Wells/Madden Park/Darrow Homes/Wells Extension Wentworth Gardens C H I C A G O H O U S I N G A U T H O R I T Y CHICAGO HOUSING AUTHORITY DEVELOPMENTS The maps below indicate the locations of the Chicago Housing Authority’s (CHA) family, senior, and scattered site properties in the City of Chicago. -

What the Demolition of Public Housing Teaches Us About the Impact of Racial Threat on Political Behavior”

Online Appendix for \What the Demolition of Public Housing Teaches Us About the Impact of Racial Threat on Political Behavior" Details of the Process of Demolition of Public Housing in Chicago Residents of public housing who were relocated were moved to what is known as \Section 8" housing, which is where residents are provided with vouchers to help pay for housing in private facilities. In demolishing the projects, HUD and the CHA were following the law from Section 202 of the Omnibus Consolidated Rescissions and Appropriations Act of 1996. An internal HUD audit describes the relevant part of Section 202 as follows: The public housing developments that were subject to Section 202 must have been on the same or contiguous sites, must have been more expensive than Section 8 tenant-based assistance, could not have been revitalized through reasonable programs, and must have had 300 or more dwelling units and had a vacancy rate of at least 10 percent for dwelling units not in funded on-schedule modernization programs. Section 202 requires that a public housing development's cost of operations be analyzed to determine whether it is more expensive to renovate and operate the low-income housing units than it is to provide Section 8 assistance to current residents and operate the low-income housing units than it is to provide Section 8 assistance to current residents and relocate them to other available develop- ments. For a public housing development for which revitalization is deemed the more expensive option, additional analysis is undertaken to assess its long-term viability if revitalized.