Foodcounts-Assessment FINAL4.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Helping You Find the Right Community and Social Services. Joint Message from The

211 ANNUAL REPORT 2014 ANNUAL REPORT 2014 Helping you find the right community and social services. Joint Message from the Chair and Executive Director The 2014 calendar year was the first full year of Twitter have tripled. operation for 211, following launch of the service on February11, 2013, and it has been a year of Calendar 2014 has also been a year of strategic growth. Monthly average call volumes as well as partnerships. In late 2013, 211NS launched visits to the 211 website (www.ns.211.ca) have an awareness campaign directed at “caring increased by 30% over the previous year. This growth professionals” including clergy, social workers, is the result of expanding awareness throughout emergency responders, health care and educational Nova Scotia, which continues to be a priority for professionals. We are very pleased to report our team. This priority was reflected in the hiring of that several “caring professional” organizations a full time Community Relations Officer in January have joined the campaign. The College of Family 2014, dedicated to promotion of 211 through Physicians of Nova Scotia promoted 211 in April communications and outreach. through a directed mail out to more than 1,100 family physicians. Fire Officer and paramedic associations Organizations across Nova Scotia continue to included 211 on the agenda of annual conferences demonstrate strong support for 211. In 2014, our and in December, the Association of Chiefs of Police team responded to more than 100 requests for announced that 211 would be promoted as part of presentations. We are grateful to the many service the tool kit provided to all Police Officers in Nova providers who have helped spread the word about Scotia. -

The Power of Innovation and Immigration

19 THE POWER OF INNOVATION AND IMMIGRATION HALIFAX PARTNERSHIP ANNUAL REPORT HALIFAX PARTNERSHIP: ANNUAL REPORT 2018-19 1 THE POWER OF INNOVATION AND IMMIGRATION Halifax’s residents and businesses are driven to succeed. The power of innovation and immigration is critical to this success. Innovation allows local businesses to compete on a world stage and become more productive. Immigration ensures we have the people our businesses and communities need to grow. We continue to maximize the power of innovation and immigration in an aligned effort that fuels economic growth and development for our region. 19 Messages 4 This is Halifax 6 Accelerating Growth in Halifax 8 2018-19 Results 10 Promote and Maximize Growth 13 Attract and Retain Talent 16 Align Economic Development 20 Pursue an Organizational Culture of Excellence 21 Financial Overview 22 Our Board of Directors 23 Our Investors 23 2 THE POWER OF INNOVATION AND IMMIGRATION Cover photo credit: Jerry Lynds www.realtygeek.ca Message from Mayor Mike Savage Message from John Rogers, Interim President & CEO Great cities grow from a It’s been another strong year for population growth in It has been quite a year at the brought innovative minds together to thrive and create multiplicity of ideas and our city, with more young people and more Canadian Halifax Partnership, ranging from in collaborative spaces. We have seen more startups the work of many hands. newcomers choosing to make a home here. As a deep loss, significant changes and and scaleups choose Halifax as their launching pad. They may start with city, we welcome their energy and see the benefits transition, to continued progress This is just the beginning. -

WIHW Halifax, CANADA Report

Halifax, CANADA Report - 2017 2017 was the fourth year for Halifax to celebrate World Interfaith Harmony Week (WIHW). This year something tragic happened that made an impact on the whole country. Visits to Sacred Spaces are at the heart of our program, and on January 29th, the very same day that our Sacred Spaces began; six people were murdered in a Canadian sacred space. It happened in Quebec, a different Canadian province; however, it struck at the heart of all Canadian people. Our hearts grieved for those who died and for the loved ones who lost a father, husband, teacher, or friend. Our hearts grieved for Muslim sisters and brothers who were afraid in their schools, homes, streets, and sacred spaces. And together with our mayor we [Photo: Jane Woodford, MetroNews Halifax] rallied. With immediate response, thousands of Haligonians filled the Grand Parade reaching out to offer care and support. World Interfaith Harmony Week helped to strengthen us all. As one participant in our Program commented, “I was surprised how hopeful I felt by the end of the week. It felt like an extremely timely antidote to the fear and hopelessness engendered by the attack of the mosque in Quebec.” (Sarah Michleh, Jewish, Interfaith Engagement participant, environmentalist) In 2017 our experience of WIHW expanded and deepened in so many ways. New collaborations, especially with the Local Immigration Partnership, and Mount Saint Vincent University’s International Education Centre, along with the participation of three new faith communities, led to increased creativity, participation, and a stronger program. We see growth in our endeavours reflected in the strong local response to world events, in increased participation in the Interfaith Engagement Certificate Program, in the numbers who attended events, and in the eagerness of people to become ambassadors for the Week, including Halifax Regional Police. -

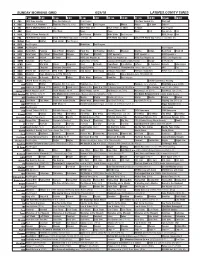

Meeting List Updated November 8Th Sunday Downtown Dartmouth 11:00 A.M

Alcoholics Anonymous Halifax Regional Municipality Meeting List Updated November 8th Sunday Downtown Dartmouth 11:00 a.m. Closed, Discussion, Wheelchair Access 3 Dundas St, Dartmouth, NS Halifax Sunday Morning 11 a.m. Discussion, Open, Wheelchair Access 2502 Brunswick St, Halifax, NS B3K 3A7, Canada George Dixon Centre Serenity Sisters 12 p.m. https://zoom.us/j/87384191757 Meeting ID: 873 8419 1757 Access code: 261479 Downtown Halifax Group 7 p.m. https://zoom.us/j/210979251?pwd=Z3FSaTBJb0M3NWc1UFFYNjdMMkdkUT09 Meeting ID: 210 979 251 Access code: 034936 Downtown Halifax Group 7 p.m. Closed, Discussion 1479 Barrington St, Halifax, NS B3J 1Z2, Canada Four Seasons Group 10 a.m. https://us04web.zoom.us/j/149787455 Meeting ID: 149 787 455 Rise and Shine Meeting 7 a.m. AA Daily Reflections reading will anchor the discussion https://us04web.zoom.us/j/78155434596 Meeting ID: 781 5543 4596 Access code: 716523 Sunday, November 8, 2020 P a g e | 1 Alcoholics Anonymous Halifax Regional Municipality Safety Net Meeting 5:30 p.m. Topic / discussion meeting https://zoom.us/j/162463507?pwd=cTJ6ekZ2ajJQMWpIMEkrRU5NTTZVUT09 Meeting ID: 162 463 507 Access code: 902209 Night Serenity 7 p.m. Discussion, Open 6670 Bayers Rd, Halifax, NS B3L 3A4, Canada Sunrise 7:30 p.m. https://zoom.us/j/82164070946 Meeting ID: 821 640 70946 Access code: 396574 Sunday Night Serenity meeting entrance is now the back entrance off George Dauphinee Ave. Cole Harbour Group 8 p.m. Open discussion 90 Lucien Dr, Dartmouth, NS St. Margaret’s Bay Group 8 p.m. Open discussion 12494 Peggys Cove Rd, Tantallon, NS B3Z 2M7, Canada Monday Grateful group 7 p.m. -

Bayou Boogaloo Authentic Cajun & Creole Cuisine

120 West Main Street, Norfolk, Virginia 23510 P: 757.441.2345 • W: festevents.org • E: [email protected] Media Release Media Contact: Erin Barclay For Immediate Release [email protected] P: 757.441.2345 x4478 Nationally Known New Orleans Chefs Serve Up Authentic Cajun & Creole Cuisine at 25th Annual Bayou Boogaloo and Cajun Food Festival presented by AT&T Friday, June 20 – Sunday, June 22, 2014 Town Point Park, Downtown Norfolk Waterfront, VA • • • NORFOLK, VA – (May 27, 2014) – Nothing says New Orleans like the uniquely delicious delicacies and distinctive flavor of Cajun & Creole cuisine! Norfolk Festevents is bringing nationally known chefs straight from New Orleans to Norfolk to serve up the heart and soul of Louisiana food dish by dish at the 25th Annual AT&T Bayou Boogaloo & Cajun Food Festival starting Friday, June 20- Sunday, June 22, 2014 in Town Point Park in Downtown Norfolk, VA. Norfolk’s annual “second line” with New Orleans’ unique culture spices it up this year with the addition of multiple New Orleans chefs that are sure to bring that special spirit to life in Town Point Park. Cooking up their famous cajun & creole cuisines are Ms. Linda The Ya-ka-Mein Lady, Chef Curtis Moore from the Praline Connection, Chef Woody Ruiz, New Orleans Crawfish King Chris “Shaggy” Davis, Jacques-Imo’s Restaurant, Edmond Nichols of Direct Select Seafood, Chef Troy Brucato, Cook Me Somethin’ Mister Jambalaya and more! They have been featured on such television shows as Anthony Bourdain’s “No Reservations”, Food Networks highly competitive cooking competition “Chopped”, “Food Paradise” and “The Best Thing I Ever Ate”. -

TV Listings Aug21-28

SATURDAY EVENING AUGUST 21, 2021 B’CAST SPECTRUM 7 PM 7:30 8 PM 8:30 9 PM 9:30 10 PM 10:30 11 PM 11:30 12 AM 12:30 1 AM 2 2Stand Up to Cancer (N) NCIS: New Orleans ’ 48 Hours ’ CBS 2 News at 10PM Retire NCIS ’ NCIS: New Orleans ’ 4 83 Stand Up to Cancer (N) America’s Got Talent “Quarterfinals 1” ’ News (:29) Saturday Night Live ’ Grace Paid Prog. ThisMinute 5 5Stand Up to Cancer (N) America’s Got Talent “Quarterfinals 1” ’ News (:29) Saturday Night Live ’ 1st Look In Touch Hollywood 6 6Stand Up to Cancer (N) Hell’s Kitchen ’ FOX 6 News at 9 (N) News (:35) Game of Talents (:35) TMZ ’ (:35) Extra (N) ’ 7 7Stand Up to Cancer (N) Shark Tank ’ The Good Doctor ’ News at 10pm Castle ’ Castle ’ Paid Prog. 9 9MLS Soccer Chicago Fire FC at Orlando City SC. Weekend News WGN News GN Sports Two Men Two Men Mom ’ Mom ’ Mom ’ 9.2 986 Hazel Hazel Jeannie Jeannie Bewitched Bewitched That Girl That Girl McHale McHale Burns Burns Benny 10 10 Lawrence Welk’s TV Great Performances ’ This Land Is Your Land (My Music) Bee Gees: One Night Only ’ Agatha and Murders 11 Father Brown ’ Shakespeare Death in Paradise ’ Professor T Unforgotten Rick Steves: The Alps ’ 12 12 Stand Up to Cancer (N) Shark Tank ’ The Good Doctor ’ News Big 12 Sp Entertainment Tonight (12:05) Nightwatch ’ Forensic 18 18 FamFeud FamFeud Goldbergs Goldbergs Polka! Polka! Polka! Last Man Last Man King King Funny You Funny You Skin Care 24 24 High School Football Ring of Honor Wrestling World Poker Tour Game Time World 414 Video Spotlight Music 26 WNBA Basketball: Lynx at Sky Family Guy Burgers Burgers Burgers Family Guy Family Guy Jokers Jokers ThisMinute 32 13 Stand Up to Cancer (N) Hell’s Kitchen ’ News Flannery Game of Talents ’ Bensinger TMZ (N) ’ PiYo Wor. -

The Walking Dead,” Which Starts Its Final We Are Covid-19 Safe-Practice Compliant Season Sunday on AMC

Las Cruces Transportation August 20 - 26, 2021 YOUR RIDE. YOUR WAY. Las Cruces Shuttle – Taxi Charter – Courier Veteran Owned and Operated Since 1985. Jeffrey Dean Morgan Call us to make is among the stars of a reservation today! “The Walking Dead,” which starts its final We are Covid-19 Safe-Practice Compliant season Sunday on AMC. Call us at 800-288-1784 or for more details 2 x 5.5” ad visit www.lascrucesshuttle.com PHARMACY Providing local, full-service pharmacy needs for all types of facilities. • Assisted Living • Hospice • Long-term care • DD Waiver • Skilled Nursing and more Life for ‘The Walking Dead’ is Call us today! 575-288-1412 Ask your provider if they utilize the many benefits of XR Innovations, such as: Blister or multi-dose packaging, OTC’s & FREE Delivery. almost up as Season 11 starts Learn more about what we do at www.rxinnovationslc.net2 x 4” ad 2 Your Bulletin TV & Entertainment pullout section August 20 - 26, 2021 What’s Available NOW On “Movie: We Broke Up” “Movie: The Virtuoso” “Movie: Vacation Friends” “Movie: Four Good Days” From director Jeff Rosenberg (“Hacks,” Anson Mount (“Hell on Wheels”) heads a From director Clay Tarver (“Silicon Glenn Close reunited with her “Albert “Relative Obscurity”) comes this 2021 talented cast in this 2021 actioner that casts Valley”) comes this comedy movie about Nobbs” director Rodrigo Garcia for this comedy about Lori and Doug (Aya Cash, him as a professional assassin who grapples a straight-laced couple who let loose on a 2020 drama that casts her as Deb, a mother “You’re the Worst,” and William Jackson with his conscience and an assortment of week of uninhibited fun and debauchery who must help her addict daughter Molly Harper, “The Good Place”), who break up enemies as he tries to complete his latest after befriending a thrill-seeking couple (Mila Kunis, “Black Swan”) through four days before her sister’s wedding but decide job. -

'Tremendously Misunderstood'

$1 Serving our communities since 1889 — www.chronline.com Mid-Week Edition Snow Blankets Thursday, County / Main 16 Jan. 12, 2017 Lighting Up the City Tribe Buoys Dock Plans Fort Borst Christmas Display Raises More Chehalis Tribe Makes Donation Toward New Than $20,000, Six Tons of Food / Main 4 Wheelchair Ramp at Fort Borst Pond / Main 7 Citizen Group, City Make Amends on Resources for Homeless Justyna Tomtas OPEN ARMS: Councilors gized to the Centralia City tion to that to come to some sort / [email protected] Council on behalf of the group of agreement or resolution,” he Chris Shilley, of Express Support for for the organization’s act of civil said regarding the ordinance Open Arms, Homeless Population disobedience after they decided that prohibited their actions. addresses the Cen- to attach items to trees at George He said he’d like to come tralia City Council After Removal of Items Washington Park following city up with an agreement on a on Tuesday night From Park staff’s removal of the clothing timeframe when the organiza- about the group’s based on a city ordinance. tion would be allowed to hang eforts to help the By Justyna Tomtas After apologizing to the up items, which include hats, homeless popula- [email protected] council, Shilley asked the city to scarves and mittens, at Wash- tion in the city. work with the group in their fu- ington Park to help the local On Tuesday night, Chris ture efforts. Shilley, of Open Arms, apolo- “I’m here to ask for an exemp- please see GROUP, page Main 13 Lewis Gather Church Feeds, County ‘Tremendously Clothes and Supports Centralia’s Growing Might Homeless Population Replace Misunderstood’ Manager Living in Arizona TRAVEL: Current Risk Manager Moved Last Year, Stayed With County at Request of Commissioners By Aaron Kunkler [email protected] Lewis County may begin searching for a replacement risk manager following Pau- lette Young’s move to Arizo- na in September. -

Sunday Morning Grid 6/24/18 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 6/24/18 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program PGA Tour Special (N) PGA Golf 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) NBC4 News Paid Program House House 1st Look Extra Å 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News News Paid Eye on L.A. Paid 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX FIFA World Cup Today 2018 FIFA World Cup Japan vs Senegal. (N) FIFA World Cup Today 2018 FIFA World Cup Poland vs Colombia. (N) 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Buddhism Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Kitchen Mexican Martha Belton Real Food Food 50 28 KCET Zula Patrol Zula Patrol Mixed Nutz Edisons Kid Stew Biz Kid$ KCET Special Å KCET Special Å KCET Special Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Paid NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Como Dice el Dicho La casa de mi padre (2008, Drama) Nosotr. Al Punto (N) 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress K. -

ATLANTIC CANADA OPPORTUNITIES AGENCY ATLANTIC POLICY RESEARCH INITIATIVE Final Report

ATLANTIC CANADA OPPORTUNITIES AGENCY ATLANTIC POLICY RESEARCH INITIATIVE Final Report 18th Annual Atlantic Conference on Public Administration Stronger Together: Indigenous Reconciliation and Sustainable Growth in Atlantic Canada January 25th – 26th, 2017 1 Table of Contents Conference Notes ..................................................................................................................... 2 Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................. 3 Letter from the Chair .............................................................................................................. 4 Conference Highlights ............................................................................................................. 5 Opening Prayer and Smudge .............................................................................................................. 5 The Role of Elders .............................................................................................................................. 6 Setting the Stage: Why is Reconciliation Important? ......................................................................... 6 Netukulimk – A Path to Reconciliation? ............................................................................................. 7 Keynote Address – Mayor Mike Savage ........................................................................................... 10 Reconciliation in Action: Pathways to Shipbuilding ....................................................................... -

Buen Provecho!

www.oeko-tex.com International OEKO-TEX® Cookbook | Recipes from all over the world | 2012 what´scooking? mazaidar khanay ka shauk Guten Appetit! Trevlig måltid Buen provecho! Smacznego 尽享美食 Καλή σας όρεξη! Enjoy your meal! Dear OEKO-TEX® friends The OEKO-TEX® Standard 100 is celebrating its 20th anniversary this year. We would like to mark this occasion by saying thank you to all companies participating in the OEKO-TEX® system, and to their employees involved in the OEKO-TEX® product certification in their daily work. Without their personal commitment and close co-operation with our teams around the globe, the great success of the OEKO-TEX® Standard 100 would not have been possible. As a small gift the OEKO-TEX® teams from our worldwide member institutes and representative offices have created a self-made cooking book with favourite recipes which in some way has the same properties as the OEKO-TEX® Standard 100 that you are so familiar with – it is international, it can be used as a modular system and it illustrates the great variety of delicious food and drinks (just like the successfully tested textiles of all kinds). We hope that you will enjoy preparing the individual dishes. Set your creativity and your taste buds free! Should you come across any unusual ingredients or instructions, please feel free to call the OEKO-TEX® employees who will be happy to provide an explanation – following the motto “OEKO-TEX® unites and speaks Imprint the same language” (albeit sometimes with a local accent). Publisher: Design & Layout: Bon appetit! -

International Association of Culinary Professionals 26Th Annual Conference April 21-24, 2004 Baltimore, Maryland

International Association of Culinary Professionals 26th Annual Conference April 21-24, 2004 Baltimore, Maryland General Session “Is Globalization Changing The Way The World Eats?” Speaker: Dr. Tyler Cowen Thank you all, and good morning. Let’s start with slide one. That’s me, the obsessive, and obsessive is the key word here. I’m food obsessive. I have several obsessions actually, but today we talk about food. When I get home, my wife will ask me, “how did it go?”, and my answer will be, “the breakfast was excellent!” So I travel a great deal, I cook a great deal, and I write an on-line dining guide. I’m one of those people who lives to eat. For a long time now, I have been writing about culture, and creativity, and diversity, and now I am writing about food. And my interest in food really stems from my life, and that is from my obsessive nature. I wanted to be going out there, eating in the best places possible. With this attitude every meal counts. But if every meal is going to count, you have to know how to eat. So let’s go to the next slide. I have a theory of food. It’s a fairly simple theory, it’s not perfect, and there are some exceptions. But what makes for great food? Three items: You need competition, experimentation, and pride. Competition – if you are in a strange city, or strange country, and you want to know where to eat, go to the cuisine that is represented by the greatest number of restaurants.