Distribution and Invasiveness of a Colonial Ascidian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

District Collector, Thoothukudi

Shri M.Ravi Kumar, I.A.S., District Collector, Thoothukudi. MESSAGE I am much pleased to note that at the instance of Dept. of Economics & Statistics, the District Statistical Handbook of Thoothukudi is being brought out for the year 2015. As a compendium of essential Statistics pertaining to the District, this Hand Book will serve as a useful Source of reference for Research Scholars, Planners, Policy makers and Administrators of this District The Co-operation extended by various heads of department and Local bodies of this district in supplying the data is gratefully acknowledged. Suggestions are welcome to improve the quality of data in future. Best wishes… Date: R.BabuIlango, M.A., Deputy Director of Statistics, Thoothukudi District. PREFACE The Publication of District Statistical Hand Book-2015 Presents a dossier of different variants of Thoothukudi profile. At the outset I thank the departments of State, Central Government and public sector under taking for their Co-operation in furnishing relevant data on time which have facilitate the preparation of hand book. The Statistical Tables highlight the trends in the Development of Various sectors of the Thoothukudi District. I am indebted to Thiru.S.Sinnamari, M.A.,B.L., Regional Joint Director of Statisitcs for his valuable Suggestions offered for enhancing quality of the book. I would like to place on record my appreciation of the sincere efforts made by Statistical officers Thiru.A.sudalaimani, (computer), Thiru.P.Samuthirapandi (Schemes) and Statistical Inspector Thiru.N.Irungolapillai. Suggestions and points for improving this District Statistical Hand Book are Welcome. Date : Thoothukudi District Block Maps Thoothukudi District Taluk Maps SALIENT FEATURES OF THOOTHUKUDI DISTRICT Thoothukudi District carved out of the erstwhile Thirunelveli District on October 20, 1986. -

THOOTHUKUDI ( the PEARL CITY)

THOOTHUKUDI ( The PEARL CITY) Places of interest in Thoothukudi District Thoothukudi Genral Information Area: 4621 sq.km Population: 17,38,376 STD Code: 0461 Access: Air: Nearest Air Port at Vagaikulam 14 kms from Thoothukudi. Daily Flight to Chennai Rail: Connected to Chennai, Mysore, Bangalore, Tirunelveli, and Tiruchendur, Road: Good connectivity by Road. Frequent bus services to all important places. Thoothukudi is traditionally known for pearl fishing and shipping activities, production of salt and other related business. This is a port city in the southern region of Tamilnadu. This is a natural port, from this place freedom fighter V.O.Chidambaranar operated the Swadeshi shipping company during the British rule. Now Thoothukudi is a bustling town with business activities. Panimaya Matha Church (Shrine Basilia of Our Lady of Snow”) is a famous church built by the Portugese in 1711. Every year on 5th August the church festival is conducted in a grand manner which attracts a large number of devotees from all faiths. Tiruchendur Thiruchendur is one of the major pilgrim centres of South India. This Temple is situated at a distance of 40 kms from Thoothukkudi. The sea-shore temple is dedicated to Lord Muruga, is one of the six abodes of Lord Muruga. (Arupadi Veedu).The nine storied tier temple tower of height 157 feet belongs 17th century AD. Visiting Valli Cave, taking sea-bath, and bathing in Nazhikkinaru are treated as holy one. It is well connected by bus service to all over Tamilnadu and train services to Tirunelveli and Chennai. Vallanadu Blackbuck Sanctuary The Sanctuary is located in Vallanadu village of Srivaikundam Taluk on Tirunelveli – Thoothukudi road at a distance of 18Km from Tirunelveli. -

Sur-Vey of Cottage Industries

l!- 1 PRELIMINARY REPORT ON THE SUR-VEY OF COTTAGE INDUSTRIES IN THE jiADUHA, RA~INAD, 11RICHINOPOLY AND TINNEVELLY DISTBICTS BY D. NARAYANA RAO, B.A., Special 0fficer for the Survey ol Cottage Industries MADRA8 PlU~TEII BY THE l'l!JPEIUNTENDENT, GOVERNMENT PRESS 19 26 _ _I PRELIMINARY· REPORT ON THE SURVEY OF COTTAGE INDUSTRIES IN THE MADURA, RAMNAD, TRICHINO POLY AND TINNEVELLY DISTRICTS. CONTENTS. - PAGE 1. Introduction 1-2 2. Notes on Hand-spinning 2-6 3. Handloom weaving " 6-22 4. )) Dyeing and printing .. 23-27 5. ,, Wool spinning and weaving 27-30 6. " Kom mat-making .• 30-36 7. Cotton carpet weaving " 36-39 8. , Coconut coir making 39-43 9. ,, Industries connected with palmyras 43-50 10. " Extraction of sunnhemp and aloe fibre and manu- fae:ture . , • . • • . • • 50-52 11. ,, Match making 52-55 12. , Lace and emln·oidery works 55-58 13. , Gold and silver lace thread rualing 58-60 14. ,, Metal industry .. 60-68 15. , Manufacture of iron safes and 1rass locks 68-69 16. , rheroots and beedi manufactnrf' 69-72 .' 17. , Bangle making 72-73 18. )) Doll or toy industl'y .. 73-76 ii ,CONTENTS 19. Notes on Minor industries- PAGE i. Lace and velvet caps 76-77 ii. Painting 77-78 iii. Wooden statue 78 ir. Silk rearing 78 v. Wood carving 78-79 vi. Making of brass, silver and horn insects . • 79-80 vii. Making of fish nets 80 viii. Pottery 80-82 ix. Oil pressing 82-83 x. Chanks and chank beads 83-84 xi. Tanning 85 :rii. Boot and shoe making 85-86 Yiii. -

Pembagian Waris Pada Komunitas Tamil Muslim Di Kota Medan

PEMBAGIAN WARIS PADA KOMUNITAS TAMIL MUSLIM DI KOTA MEDAN TESIS Oleh MUMTAZHA AMIN 147011016/M.Kn FAKULTAS HUKUM UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA MEDAN 2016 Universitas Sumatera Utara PEMBAGIAN WARIS PADA KOMUNITAS TAMIL MUSLIM DI KOTA MEDAN TESIS Diajukan Untuk Memperoleh Gelar Magister Kenotariatan Pada Program Studi Magister Kenotariatan Fakultas Hukum Universitas Sumatera Utara Oleh MUMTAZHA AMIN 147011016/M.Kn FAKULTAS HUKUM UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA MEDAN 2016 Universitas Sumatera Utara Judul Tesis : PEMBAGIAN WARIS PADA KOMUNITAS TAMIL MUSLIM DI KOTA MEDAN Nama Mahasiswa : MUMTAZHA AMIN NomorPokok : 147011016 Program Studi : Kenotariatan Menyetujui Komisi Pembimbing (Dr. Edy Ikhsan, SH, MA) Pembimbing Pembimbing (Dr. T. Keizerina Devi A, SH, CN, MHum) (Dr.Utary Maharany Barus, SH, MHum) Ketua Program Studi, Dekan, (Prof.Dr.Muhammad Yamin,SH,MS,CN) (Prof.Dr.Budiman Ginting,SH,MHum) Tanggal lulus : 16 Juni 2016 Universitas Sumatera Utara Telah diuji pada Tanggal : 16 Juni 2016 PANITIA PENGUJI TESIS Ketua : Dr. Edy Ikhsan, SH, MA Anggota : 1. Dr. T. Keizerina Devi A, SH, CN, MHum 2. Dr. Utary Maharany Barus, SH, MHum 3. Prof. Dr. Muhammad Yamin, SH, MS, CN 4. Dr. Rosnidar Sembiring, SH, MHum Universitas Sumatera Utara SURAT PERNYATAAN Saya yang bertanda tangan dibawah ini : Nama : MUMTAZHA AMIN Nim : 147011016 Program Studi : Magister Kenotariatan FH USU Judul Tesis : PEMBAGIAN WARIS PADA KOMUNITAS TAMIL MUSLIM DI KOTA MEDAN Dengan ini menyatakan bahwa Tesis yang saya buat adalah asli karya saya sendiri bukan Plagiat, apabila dikemudian hari diketahui Tesis saya tersebut Plagiat karena kesalahan saya sendiri, maka saya bersedia diberi sanksi apapun oleh Program Studi Magister Kenotariatan FH USU dan saya tidak akan menuntut pihak manapun atas perbuatan saya tersebut. -

Water Resources Organisation Public Works Department

GOVERNMENT OF TAMIL NADU Water Resources Organisation Public Works Department RISK ASSESSMENT AND DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN FOR FOR CONSTRUCTION OF GROYNES AT PERIYATHALAI IN TIRUCHENDUR TALUK OF THOOTHUKUDI DISTRICT Flat No: 2C, IInd floor, Jai Durga Apartment, 38/2, First Avenue, Ashok Nagar, Chennai-600 083. Tel.: 24710477 / Tel Fax: 044-24714424 E-mail: [email protected] JULY 2014 Public Works Department EIA Studies for Construction of Groyne at Periyathalai, Tiruchendur Taluk, Thoothukudi District 1.0 INTRODUCTION Groins are considered to be one of the best methods to protect eroding coastline. The coast along the state of Tamil Nadu is very dynamic due to various developmental activities along the coast. This causes sea erosion and hence loss of land to the seas. Periyathalai, with geographical coordinates 8°20′11.043″ N and 77°58′43.134″ E is located in Tiruchendur Taluk of Thoothukudi District in Southern Tamilnadu. This area is a sandy beach prone to littoral drift and sever erosion. The boats are anchored at the sea thus leaving them to the impacts of the open seas. In order to protect the coast and provide a safe landing for the boats, Public Works Department of Government of Tamil Nadu is proposing to construct the Groyne at coastal stretch in Periyathalai. 2.0 DISTRICT PROFILE Geographical Locations of the District and Project site Thoothukudi District lies between latitude 8o 45’ Northern and longitude 78o 11’ Eastern with an area of about 4635 Sq.km. The district is bounded on west by Tirunelveli District, on the north by Virudhunagar and Ramanathapuram district, on south by Bay of Bengal and on the east by Bay of Bengal. -

The Dutch East India Company Settlements in Tamil Nadu, 1602 -1825 – a Study in Political Economy

THE DUTCH EAST INDIA COMPANY SETTLEMENTS IN TAMIL NADU, 1602 -1825 – A STUDY IN POLITICAL ECONOMY Thesis submitted to the Bharathidasan University in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Submitted by S. RAVICHANDRAN, M.A., M.Phil., Supervisor & Guide Dr. N. RAJENDRAN, M.A., M.Phil., Ph.D. DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BHARATHIDASAN UNIVERSITY TIRUCHIRAPPALLI – 620 024 November – 2011 Dr. N. RAJENDRAN Department of History Dean of Arts, Professor & Head Bharathidasan University Tiruchirappalli – 24 CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the Ph.D. thesis entitled “The Dutch East India Company Settlements In Tamil Nadu, 1602 -1825 – A Study In Political Economy” is a bonafide record of the research work carried out by Thiru. S. Ravichandran, under my guidance and supervision for the award of Ph.D. Degree in History in the Department of History, Bharathidasan University, Tiruchirappalli during the period 2006 - 2011 and that anywhere the thesis has not previously formed the basis for the award of any degree, diploma, dissertation, thesis, associateship or any other similar title to the candidate. This is also to certify that this thesis is an original, independent work of the candidate. (N. RAJENDRAN) Supervisor & Guide DECLARATION I hereby declare that this thesis entitled “The Dutch East India Company Settlements In Tamil Nadu, 1602 -1825 – A Study In Political Economy” has been originally carried out by me under the guidance and supervision of Dr. N. Rajendran, Dean of Arts, Professor and Head, Department of History, Bharathidasan University, Tiruchirappalli, and submitted for the award of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in Bharathidasan University, Tiruchirappalli is my original and independent work. -

Thoothukudi District

DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN 2017 for THOOTHUKUDI DISTRICT on Sendai framework for Disaster Risk Reduction (2015-2030) Index Page Sl.No Chapters No 1 Index / Content of the plan 1-2 2 List of abbreviations present in the plan 3 3 Introduction 4-5 4 District Profile 6-17 5 Disaster Management Goals (2017-30) 18-19 Hazard, Risk and Vulnerability analysis with sample maps & link to all vulnerable maps vulnerability based on 6 a) Infrastructure 20-38 b) Socio – Economic Groups 7 Institutional Mechanism 39-54 8 Preparedness 55-61 9 Prevention & Mitigation Plan (2015-30) 62-87 Response Plan – Including Incident Response System 10 (What Major & Minor Disasters will be addressed through 88-110 mitigation(Covering Rescue,measures) Evacuation , Relief and Industrial Pollution) 11 Recovery and Reconstruction Plan 111-114 Mainstreaming of Disaster Management in Developmental Plans Kudimaramath (PWD) G.O.Ms.No. 50 (Industries Dept – Regarding desilting of tanks) 12 THAI (RD & PR) 115-116 CDRRP MGNREGA Dry land farming ADB – Climate Change Adaptation Scheme IAMWARM etc. Community & other Stakeholder participation CBDRM First Responders 13 NGO‘s 117-122 Red Cross Welfare Associations Local Bodies etc., Linkages / Co-ordination with other agencies for Disaster 14 123-154 Management 1 Budget and Other Financial allocation – Outlays of major 15 155 Schemes Monitoring and Evaluation 16 Hon‘ble Ministers 156-175 Monitoring Officers Inter Departmental Zonal Team (IDZT) Risk Communication strategies 17 176-177 (Telecommunication/VHF/Media/CDRRP etc.) Important Contact numbers and provision for link to detailed 18 178-186 information Do's and Don'ts during all Possible hazards including Heat 19 wave 187-192 20 Important G.Os 193-194 21 Linkages with IDRN 195-240 Specific issues on various Vulnerable Groups have been 22 241-248 addressed 23 Mock Drill Schedules 249 24 Date of approval of DDMP by DDMA 250 2 2. -

Tamil Nadu Government Gazette

© GOVERNMENT OF TAMIL NADU [Regd. No. TN/CCN/467/2009-11. 2009 [Price: Rs. 16.00 Paise. TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY No. 6] CHENNAI, WEDNESDAY, FEBRUARY 18, 2009 Maasi 6, Thiruvalluvar Aandu–2040 Part VI—Section 4 Advertisements by private individuals and private institutions CONTENTS PRIVATE ADVERTISEMENTS Pages Change of Names .. .. 191-229 NOTICE NO LEGAL RESPONSIBILITY IS ACCEPTED FOR THE PUBLICATION OF ADVERTISEMENTS REGARDING CHANGE OF NAME IN THE TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE. PERSONS NOTIFYING THE CHANGES WILL REMAIN SOLELY RESPONSIBLE FOR THE LEGAL CONSEQUENCES AND ALSO FOR ANY OTHER MISREPRESENTATION, ETC. (By Order) Director of Stationery and Printing. CHANGE OF NAMES Thirumathi C. Rakkammal (Hindu), wife of Thiru I, K. Munusamy, son of Thiru A. Kuppan, born on N. David, born on 2nd June 1972 (native district: Sivagangai), 24th August 1978 (native district: Villupuram), residing at residing at No. 1/127, Satharasankottai Post, Sivagangai- No. 3/40, Adimoolam Street, Sakkarapuram, Gingee, 630 561, has converted to Christianity with the name of Villupuram-604 202, shall henceforth be known D. SARAL on 20th October 1999. as K. GUNASEELAN. C. RAKKAMMAL. K. MUNUSAMY. Satharasankottai, 9th February 2009. Gingee, 9th February 2009. I, A. Perumalsami, son of Thiru G. Arujanan, born on I, R. Niranj Radhan, son of Thiru R. Radha Krishnan, 1st February 1967 (native district: Thiruvannamalai), residing born on 24th May 1986 (native district: Villupuram), residing at Old No. 02, New No. 210, Nadu Street, Vadal, Vandhavasi at No. 20/2A, Ram Thulasi Apartments, Malony Road, Taluk, Thiruvannamalai-604 501, shall henceforth be known T. Nagar, Chennai-600 017, shall henceforth be known as as A. -

Construction of Groyne at Vembar Village, Vilathikulam Thaluk

Construction of groyne at Vembar Village, Vilathikulam Thaluk, Tuticorin Village – Baseline data on the marine biodiversity and Impacts on the marine biodiversity in Gulf of Mannar 1. BACKGROUND The Gulf of Mannar along the Indian coast is situated between Lat. 8° 47’ - 9° 15’ N and Long.78° 12’ - 79° 14’ E. Coral reefs are distributed on the shelfs of 21 islands, lying between Rameswaram and Kanyakumari. The Gulf of Mannar is one of the Marine Biosphere Reserves (GOMMBRE) covering an area of 10,500 sq. km. The Gulf of Mannar is one of the biologically richest and important habitats for sea algae, seagrass, coral reef, pearl banks, sacred chank bed, fin and shell fish resources, mangroves so also endemic and endangered species. The islands occur at an average distance of 8-10 km from the mainland. The 21 islands and the surrounding shallow water area covering 560 km2 were declared as Marine National Park. Coral reef area covered about 110 km2 and coral reef status during 2005 showed that about 32 km2 of reef area had already been degraded, mainly due to coral mining and destructive fishing practices. Coral diversity of Gulf of Mannar harbored 117 species and seagrass comprised 13 species. Along with corals, luxuriant and patch seagrass meadows in Gulf of Mannar provide high biodiversity. Vembar group of Islands namely Upputhanni, Puluvinichalli and Nallathanni Island these coral habitat islands located little far from the Groins sites in Vembar coast. Three proposed groynes will be constructed near inshore area of Vembar coast of Tuticorin district, by PWD / WRO. -

Biodiversity of Sponges (Phylum: Porifera) Off Tuticorin, India

Available online at: www.mbai.org.in doi:10.6024/jmbai.2020.62.2.2250-05 Biodiversity of sponges (Phylum: Porifera) off Tuticorin, India M. S. Varsha1,4 , L. Ranjith2, Molly Varghese1, K. K. Joshi1*, M. Sethulakshmi1, A. Reshma Prasad1, Thobias P. Antony1, M.S. Parvathy1, N. Jesuraj2, P. Muthukrishnan2, I. Ravindren2, A. Paulpondi2, K. P. Kanthan2, M. Karuppuswami2, Madhumita Biswas3 and A. Gopalakrishnan1 1ICAR-Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute, Kochi-682018, Kerala, India. 2Regional Station of ICAR-CMFRI, Tuticorin-628 001, Tamil Nadu, India. 3Ministry of Environment Forest and Climate Change, New Delhi-110003, India. 4Cochin University of Science and Technology, Kochi-682022, India. *Correspondence e-mail: [email protected] Received: 10 Nov 2020 Accepted: 18 Dec 2020 Published: 30 Dec 2020 Original Article Abstract the Vaippar - Tuticorin area. Tuticorin area is characterized by the presence of hard rocky bottom, soft muddy bottom, lagoon The present study deals with 18 new records of sponges found at and lakes. Thiruchendur to Tuticorin region of GOM-up to a Kayalpatnam area and a checklist of sponges reported off Tuticorin distance of 25 nautical miles from shore 8-10 m depth zone-is in the Gulf of Mannar. The new records are Aiolochoria crassa, characterized by a narrow belt of submerged dead coral blocks Axinella damicornis, Clathria (Clathria) prolifera, Clathrina sororcula, which serves as a very good substrate for sponges. Patches of Clathrina sinusarabica, Clathrina coriacea, Cliona delitrix, Colospongia coral ground “Paar” in the 10-23 m depth zone, available in auris, Crella incrustans, Crambe crambe, Hyattella pertusa, Plakortis an area of 10-16 nautical miles from land are pearl oyster beds simplex, Petrosia (Petrosia) ficiformis, Phorbas plumosus, (Mahadevan and Nayar, 1967; Nayar and Mahadevan, 1987) Spheciospongia vesparium, Spirastrella cunctatrix, Xestospongia which also forms a good habitat for sponges. -

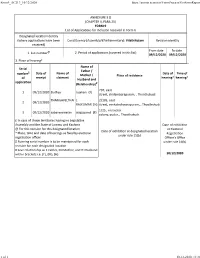

ANNEXURE 5.8 (CHAPTER V, PARA 25) FORM 9 List of Applica Ons For

Form9_AC213_10/12/2020 https://eronet.ecinet.in/FormProcess/GetFormReport ANNEXURE 5.8 (CHAPTER V, PARA 25) FORM 9 List of Applicaons for inclusion received in Form 6 Designated locaon identy (where applicaons have been Constuency (Assembly/£Parliamentary): Vilathikulam Revision identy received) From date To date 1. List number@ 2. Period of applicaons (covered in this list) 09/12/2020 09/12/2020 3. Place of hearing* Name of Serial Father / number$ Date of Name of Date of Time of Mother / Place of residence receipt claimant hearing* hearing* of Husband and applicaon (Relaonship)# 207, east 1 09/12/2020 Duthija rajakani (F) street, chidambarapuram, , Thoothukudi THANGAVELTHAI L 2/105, east 2 09/12/2020 RAJKUMAR (H) street, venkateshwarapuram, , Thoothukudi 1/25 , nesavalar 3 09/12/2020 sabareeswaran alagupandi (F) colony, pudur, , Thoothukudi £ In case of Union territories having no Legislave Assembly and the State of Jammu and Kashmir Date of exhibion @ For this revision for this designated locaon at Electoral Date of exhibion at designated locaon * Place, me and date of hearings as fixed by electoral Registraon under rule 15(b) registraon officer Officer’s Office $ Running serial number is to be maintained for each under rule 16(b) revision for each designated locaon # Give relaonship as F-Father, M=Mother, and H=Husband within brackets i.e. (F), (M), (H) 10/12/2020 1 of 1 10-12-2020, 11:31 Form9_AC213_12/12/2020 https://eronet.ecinet.in/FormProcess/GetFormReport ANNEXURE 5.8 (CHAPTER V, PARA 25) FORM 9 List of Applicaons for inclusion received in Form 6 Designated locaon identy (where applicaons have been Constuency (Assembly/£Parliamentary): Vilathikulam Revision identy received) From date To date 1. -

Tamil Nadu Government Gazette

© [Regd. No. TN/CCN/467/2012-14. GOVERNMENT OF TAMIL NADU [R. Dis. No. 197/2009. 2016 [Price : Rs. 38.40 Paise. TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY No. 34F] CHENNAI, WEDNESDAY, AUGUST 24, 2016 Aavani 8, Thunmugi, Thiruvalluvar Aandu–2047 Part VI–Section 1 (Supplement) NOTIFICATIONS BY HEADS OF DEPARTMENTS, ETC. TAMIL NADU NURSES AND MIDWIVES COUNCIL, CHENNAI. (Constituted under Tamil Nadu Act III of 1926) LIST OF NAMES OF AUXILIARY NURSE-MIDWIFE ELECTORAL ROLL FOR THE YEAR 01-01-2003 TO 31-12-2003. DTP—VI-1 Sup. (34F)—1 [ 1 ] THE TAMILNADU NURSES AND MIDWIVES COUNCIL No-140,JeyaPrakash Narayanan Maligai,Santhome High Road, Mylapore,Chennai-600004. emailID:[email protected] LIST OF NAMES OF AUXILIARY NURSE-MIDWIFE ELECTORAL ROLL FOR THE YEAR 01/01/2003 To 31/12/2003 Cat./ Sec. S.No Canditate Name & Address Particulars ANM No. & Reg.Date. 1 Ms/Mrs S. UMAYAL Diploma in Auxiliary Nurse-Midwives/Multipurpose Part :E Date Of Birth:11/04/1968, Health Workers Section:I Address:- Board of Examiners for Health Worker/ A.N.M./ D/O.SUBBIAHPILLAI,,PILAVADIPATTY, Health Visitor of the Government of TamilNadu - ANM.NO :17058 PEERKALAIKADU POST, K. PUDUVAYAL India Date :02/01/2003 VAZHI,, M.P.H.W(F) TRAINING SCHOOL, GOVT. MOHAN SIVAGANGAI DISTRICT,CHENNAI, KUMARAMANGALAM MEDICAL COLLEGE HOSPITAL, 623109 SALEM Community:-- Religon:-- From FEB/1994 To JUL/1995 JUL/1995 Mobile No :- EmailId :-- 2 Ms/Mrs A. MUNIAMMAL Diploma in Auxiliary Nurse-Midwives/Multipurpose Part :E Date Of Birth:13/04/1967, Health Workers Section:I Address:-D/O.AYANKUTTI,,KILAKKADU Board of Examiners for Health Worker/ A.N.M./ PHC, KALAVARAYAN HILLS,, Health Visitor of the Government of TamilNadu - ANM.NO :17059 SANKARAPURAM TALUK, India Date :02/01/2003 VILLUPURAM,CHENNAI, M.P.H.W(F) TRAINING SCHOOL, GOVT.