Transatlantica, 1 | 2003 Superchic(K) 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

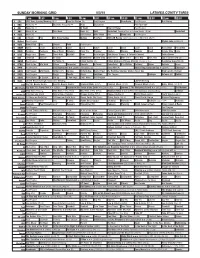

Sunday Morning Grid 5/3/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 5/3/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning (N) Å Face the Nation (N) Paid Program NewsRadio Paid Program Bull Riding 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Equestrian PGA Tour Golf 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) NBA Basketball Brooklyn Nets at Atlanta Hawks. (N) Å Basketball 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday Midday Pre-Race NASCAR Racing Sprint Cup Series: GEICO 500. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Afghan Luke (2011) (R) 18 KSCI Breast Red Paid Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Cosas Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local RescueBot RescueBot 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Cooking Fresh Simply Ming Lidia 28 KCET Raggs Fast. Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Insight Rick Steves’ Europe: A Cultural Carnival Father Brown 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY7) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly Taxi › (2004) (PG-13) 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División: Pumas vs Azul República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program 101 Dalmatians ›› (1996) Glenn Close. -

Chad Broskey Sag – Aftra – Emc

CHAD BROSKEY SAG – AFTRA – EMC Height: 6’2 Weight: 185lbs Hair: Brown Eyes: Brown TELEVISION: NASHVILLE Guest Star ABC Series SCRUBS Guest Star NBC Universal MISS GUIDED (Pilot) Recurring ABC WIZARDS OF WAVERLY.. Guest Star Disney Channel HOUSE BROKEN (Pilot) Recurring Disney Channel THE SUITE LIFE… Guest Star Disney Channel FILM: LEGALLY BLONDES Lead MGM Feature Film READ IT AND WEEP Lead Disney Channel Movie THEATRE/TOURS: LEGALLY BLONDE Warner Huntington III Norwegian Cruise Line BURN THE FLOOR Principal Vocalist Norwegian Cruise Line VEGAS: THE SHOW Frank Sinatra/Elvis Norwegian Cruise Line LEGALLY BLONDE Warner Huntington III Beef & Boards Theatre HAIRSPRAY Link Larkin Derby Dinner Playhouse DAMES AT SEA Dick Skylight Opera Theatre A CHORUS LINE Gregory Gardner CenterStage Theatre HAIRSPRAY Link Larkin Music Theatre Louisville EDUCATIONAL THEATRE: MARY POPPINS Bert Folsom Academy SWEET CHARITY Oscar Youth Performing Arts School LES MISERABLES Marius Youth Performing Arts School THE OUTSIDERS Randy Youth Performing Arts School COMMERCIALS/VOICE OVER: McDONALDS (National) FIDELITY INVESTMENTS (National) PURDUE UNIVERSITY (Regional) SMOKEY THE BEAR (V/O Regional West Coast) MORE AVAILABLE UPON REQUEST TRAINING: Youth Performing Arts School – Musical Theatre Major Gail Benedict/William Bradford Private Vocal Training Sharon Kennison/Debbie King Folsom Academy – Voice, Acting, Dance Heather Folsom Audition Technique Richard Futch, CSA Acting Coach LA Brian Chesters/Carey Anderson Vocal Coach NY Katie Pfaffle/Ben Rahaula SPECIAL SKILLS: Singer, Dancer (Tap, Jazz, Hip Hop), Juggler, Water Skiing, Drummer, Accents AGENCY: HEYMAN TALENT AGENCY – KATHY CAMPBELL (502-589-2540) . -

Tv Pg 8 07-06.Indd

8 The Goodland Star-News / Tuesday, July 6, 2010 All Mountain Time, for Kansas Central TIme Stations subtract an hour TV Channel Guide Tuesday Evening July 6, 2010 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 28 ESPN 57 Cartoon Net 21 TV Land 41 Hallmark ABC Wipeout Downfall Mind Games Local Nightline Jimmy Kimmel Live S&T Eagle CBS NCIS NCIS: Los Angeles The Good Wife Local Late Show Letterman Late 29 ESPN 2 58 ABC Fam 22 ESPN 45 NFL NBC Losing It-Jillian America's Got Talent Local Tonight Show w/Leno Late 2 PBS KOOD 2 PBS KOOD 23 ESPN 2 47 Food FOX Hell's Kitchen Local 30 ESPN Clas 59 TV Land Cable Channels 3 KWGN WB 31 Golf 60 Hallmark 3 NBC-KUSA 24 ESPN Nws 49 E! A&E Dog Dog Dog Dog Dog Dog Dog the Bounty Hunter Local 5 KSCW WB 4 ABC-KLBY AMC The Negotiator Thunderheart Local 32 Speed 61 TCM 25 TBS 51 Travel ANIM 6 Weather Last Lion of Liuwa I Shouldn't Be Alive Awesome Pawsome Last Lion of Liuwa Alive Local 6 ABC-KLBY 33 Versus 62 AMC 26 Animal 54 MTV BET The Wood Trey Songz The Mo'Nique Show Wendy Williams Show The Wood Local 7 CBS-KBSL BRAVO Housewives/NJ Housewives/NJ Griffin: My Life Double Exposure Griffin: My Life 7 KSAS FOX 34 Sportsman 63 Lifetime 27 VH1 55 Discovery CMT Local Local Extreme-Home Extreme-Home The Singing Bee The Bad News Bears 8 NBC-KSNK 8 NBC-KSNK 28 TNT 56 Fox Nws CNN 35 NFL 64 Oxygen Larry King Live Anderson Cooper 360 Larry King Live Anderson Local 9 Eagle COMEDY 29 CNBC 57 Disney South Pk S. -

Wednesday Primetime B Grid

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 5/17/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning (N) Å Face the Nation (N) Paid Program PGA: Spotlight PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Paid Cycling Tour of California, Stage 8. (N) Å Hockey 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) IndyCar Racing Indianapolis 500, Qualifying Day 2. NBA Basketball 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program Enough ›› (2002) 13 MyNet Paid Program Surf’s Up ››› (2007) 18 KSCI Breast Red Paid Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Cosas Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local RescueBot RescueBot 24 KVCR Painting Dowdle Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexican Cooking Fresh Simply Ming Lidia 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Insight Rick Steves’ Dynamic Europe: Amsterdam Orphans of the Genocide 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY7) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly The Client ››› (1994) 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) Hotel Todo Incluido La Madrecita (1973, Comedia) María Elena Velasco. República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Charlotte’s Web ››› (2006) Julia Roberts. -

Legally Blonde Cast List

Legally Blonde Cast List Elle Woods………………………………………………………………………………….Kaylie Tuttle/Greer King Emmett Forrester……………………………………...……………………………………………….Jordan Pogue Paulette Bonafonte’………………………………………………………………………..….…..…….Skyler Ward Warner Huntington III…………………..………………………………………………….….……Brittin Sullivan Brooke Wyndham………………………………………………………………………………….………Avery Bruce Professor Callahan…………………………..……………………………………………………….……Sam Gibson Vivienne Kensington……………………………………………………….………………………..Elizabeth Ring Margot………………………………………………………………….……….………….……….Brooklyn Jennings Serena…………………………………………….……………………………………….………………….Natalie Way Pilar…………….………………………………….…..……………………….………Sarah Mitchell/Kelsey Drees Kate…………………………………………………......…….………………………….…………………Nicole Vincent Gaelen…………………………………………..……………………………………………………….Bailey Weathers Tiffany………………………………………..…………………………………………………………………Rainey Ross Courtney…………………………………..……………………………………………………………..Mikee Olegario Sandi…………………………………………..………………………………………………………………..Payton King Angel…………………………………………….………………………….…………………….…………Lizzie Schaefer Enid……………………………………………...……………………………………………………………..Lauren Black Mr. Woods……………………………………..………………………………………………………….David Nichols Mrs. Woods………………………………….……………………..………………………………….Emily Freeman Chutney Wyndham…………………………...………………………………………………………Bethie Butera Kyle……………………………………....……………………………………………………………………Harris Sutton Winthrop………………………………………..………………………………………………………Lane Burchfield Judge……………………………………………………………………………………….……….Autumne Kendricks Grandmaster Chad…………………………………………………………………..……………………..DJ Boswell Dewey……………………………………………………..…….………………………..Easton -

Scholarship Opportunities

CC ROUGHER REVIEW What’s Happening at MHS February 2019 MHS February Calendar of Events SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY 1 Black History 2 Program 9am in Fine Arts Union Speech Tournament 3 4 5 •FCCLA Re- 6 7 Parent/Teacher 8 NO 9 ACT Testing gional STAR event Conferences 4-7 SCHOOL •PROGRESS pm REPORTS •JROTC Combat • Alternative 8th Dine In grade reading test • Parent/Teacher Conferences 4-7 Haskell Speech Tournament pm 10 11 PTSA 12 PROGRESS 13 Muskogee 14 Math & 15 NAEP Test- 16 Meeting 5:30 in REPORTS Youth Leader- Engineering ing Cafeteria ship Competition @ Civic Center 17 18 NO 19 20 21 22 23 • Band: Dist. Solo/Ensemble SCHOOL/PD Contest @ DAY Tahlequah All School Musical through Sunday, the 24th 24 25 26 27 28 Band Con- cert & Corona- tion SDA OK Eastern District Speech Tournament Shawn Ostrowski and Jacine Crosby of ROTC with local Civil Air Patrol pilot Danny Dunlap, went for a Cadet orientation flight on Jan. 13 along with two other cadets. Four more Cadets had a chance to fly on Jan, 27 February 2019 MHS ROUGHER REVIEW Page 2 MHS Proudly announces their 2019 All School Muskogee High School Presents Musical: Legally Blonde, the Musical. LEGALLY Join Muskogee High School as we take you on an upbeat, feel good journey of discovery that affirms the BLONDE old saying that you cannot judge a book by its cover; in The Musical this case, pink glittered cover. Based on the bestselling novel by Amanda Brown and the classic hit film, Legally Blonde the musical will take you on a high- energy adventure as Elle Woods (Tess Huffer) attempts to win back the love of her life, Warner Huntington, III (Ethan Turner). -

Legally Blonde

Legally Blonde Elle Woods; A feminist in a pink dress? What’s the story? Elle Woods • Superficial • Popular • Blonde Get’s dumped by her boyfriend who wants a serious girlfriend What’s the story? • So, she applies to Harvard Law School • Somehow, she gets in! • Her ex, Warner, has a new girlfriend. • After meeting Emmett, Elle realises she has to prove herself. What’s the story? • She is awarded a top Court Case • She then finds out it was only because her mentor, Callaghan, found her attractive and he sexually harasses her. • But, through her determination and honesty, she wins the case. What’s the story? • In the end, she marries Emmett • She helps many friends along the way • And proves that blondes can be intelligent. STEREOTYPES Culture defined by stereotypes • Elle has a clear stereotype • She manages to disprove it… • …whilst retaining her ‘look’. Elle the Elle the Elle the fashion- Blonde Intelligent conscious Stereotypes Prejudice • Stereotypes often play a big role in prejudice • Historically, America has a big issue with prejudice Racism • Even today, there are problems. FEMINISM TRADITIONAL FEMINISM ELLE’S FEMINISM About finding equality with men by Using skills that are viewed as ‘feminine’ rejecting ‘femininity’. to her advantage and embracing her Proving that women can do exactly the ‘femininity. same things as men. Accepts that men and women are different but equal in their own right. How does the film show this? • Elle solves a case that no man can, because of her knowledge of hair care. • Warner and Callaghan both are portrayed as disloyal and only really interested in sex. -

EMU Today, April 13, 2015 Eastern Michigan University

Eastern Michigan University DigitalCommons@EMU EMU Today EMU Today 2015 EMU Today, April 13, 2015 Eastern Michigan University Follow this and additional works at: http://commons.emich.edu/emu_today Recommended Citation "EMU Today, April 13, 2015." Eastern Michigan University Division of Communications. EMU Archives, Digital Commons @ EMU (http://commons.emich.edu/emu_today/640). This University Communication is brought to you for free and open access by the EMU Today at DigitalCommons@EMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in EMU Today by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@EMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. On this day...In 1997, 21-year-old Tiger Woods wins the prestigious Masters Tournament by a record 12 strokes in Augusta, Georgia. It was Woods’ first victory in one of golf’s four major championships–the U.S. Open, the British Open, the PGA Championship, and the Masters–and the greatest performance by a professional golfer in more than a century. Quote: "When you do the common things in life in an uncommon way, you will command the attention of the world." - George Washington Carver Fact: Apollo 13 was the seventh manned mission in the American Apollo space program and the third intended to land on the Moon. The craft was launched on April 11, 1970, from the Kennedy Space Center, but the lunar landing was aborted after an oxygen tank exploded two days later, crippling the Service Module (SM) upon which the Command Module (CM) depended. Despite great hardship caused by limited power, loss of cabin heat, shortage of potable water, and the critical need to jury-rig the carbon dioxide removal system, the crew returned safely to Earth on April 17. -

POPULAR DVD TITLES – As of JULY 2014

POPULAR DVD TITLES – as of JULY 2014 POPULAR TITLES PG-13 A.I. artificial intelligence (2v) (CC) PG-13 Abandon (CC) PG-13 Abduction (CC) PG Abe & Bruno PG Abel’s field (SDH) PG-13 About a boy (CC) R About last night (SDH) R About Schmidt (CC) R About time (SDH) R Abraham Lincoln: Vampire hunter (CC) (SDH) R Absolute deception (SDH) PG-13 Accepted (SDH) PG-13 The accidental husband (CC) PG-13 According to Greta (SDH) NRA Ace in the hole (2v) (SDH) PG Ace of hearts (CC) NRA Across the line PG-13 Across the universe (2v) (CC) R Act of valor (CC) (SDH) NRA Action classics: 50 movie pack DVD collection, Discs 1-4 (4v) NRA Action classics: 50 movie pack DVD collection, Discs 5-8 (4v) NRA Action classics: 50 movie pack DVD collection, Discs 9-12 (4v) PG-13 Adam (CC) PG-13 Adam Sandler’s eight crazy nights (CC) R Adaptation (CC) PG-13 The adjustment bureau (SDH) PG-13 Admission (SDH) PG Admissions (CC) R Adoration (CC) R Adore (CC) R Adrift in Manhattan R Adventureland (SDH) PG The adventures of Greyfriars Bobby NRA Adventures of Huckleberry Finn PG-13 The adventures of Robinson Crusoe PG The adventures of Rocky and Bullwinkle (CC) PG The adventures of Sharkboy and Lavagirl in 3-D (SDH) PG The adventures of TinTin (CC) NRA An affair to remember (CC) NRA The African Queen NRA Against the current (SDH) PG-13 After Earth (SDH) NRA After the deluge R After the rain (CC) R After the storm (CC) PG-13 After the sunset (CC) PG-13 Against the ropes (CC) NRA Agatha Christie’s Poirot: The definitive collection (12v) PG The age of innocence (CC) PG Agent -

Fakhrurozi a 320 020 038 School of Teacher Training

SELF-ACTUALIZATION OF ELLE WOODS IN AMANDA BROWN’S LEGALLY BLONDE MOVIE DIRECTED BY ROBERT LUKETIC: A HUMANISTIC APPROACH RESEARCH PAPER Submitted as a Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for Getting Bachelor Degree in English Department by FAKHRUROZI A 320 020 038 SCHOOL OF TEACHER TRAINING AND EDUCATION MUHAMMADIYAH UNIVERSITY OF SURAKARTA 2008 i 1 CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION A. Background of the Study Human life in the world has various kinds of needs from the lowest needs to the highest ones. Therefore, to survive, they would to try to fulfill their lower need as a motivator to be satisfied. And the human being has a hidden talent, potentials, qualities, capacities, and the full development of their abilities as the highest needs of self-actualization. Maslow’s self-actualization is the desire for self-fulfillment, to realize all one’s potentials, to become everything that one can, and to become creative in fulfill sense of the world. (Maslow in Feist, 1985:381) These needs are part of hierarchy of five levels of basic needs in Humanistic psychological theory. The Humanistic psychology regards humans as free will. They are able to make choice and free of what they want, as and addition, Humanistic also regards that human strive for growth. They have desire to develop their potential reaching the goal in life (Zimbardo and Ruch, 1980; 25-27) Need for Self-actualization is the highest human needs in Maslow’s theory. Every body has to develop their potential with their capability. To reach self-actualization needs a person will have desire to be a suitable person with his or her own potential. -

In “Legally Blonde”

® A FIELD GUIDE FOR TEACHERS TM StageNOTES A tool for using the theater across the curriculum to meet LEGALLY BLONDE National Standards for Education n Production Overview n Lesson Guides n Student Activities n At-Home Projects n Reproducibles Copyright 2007, Camp Broadway, LLC All rights reserved. This publication is based on Legally Blonde, The Musical with book by Heather Hach and music & lyrics by Laurence O’Keefe and Nell Benjamin. The content of the Legally Blonde, The Musical edition of StageNOTES: A Field Guide for Teachers is fully protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America and all other countries with which the United States has reciprocal copyright relations. All rights regarding publishing, reprint permissions, public readings, and mechanical or electronic reproduction, including but not limited to, CD-ROM, information storage and retrieval systems and photocopying, and the rights of translation into foreign languages are strictly reserved. Legally Blonde, The Musical is a trademark of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios Inc. All Rights Reserved. Printed in the United States of America. First Printing and Digital Edition: April 2007 For more information on StageNOTES and other theatre arts related programs, contact: Camp Broadway, LLC 336 West 37th Street, Suite 460 New York, New York 10018 Telephone: (212) 575-2929 Facsimile: (212) 575-3125 Email: [email protected] www.campbroadway.com CAMP BROADWAY LLC ® N e w Yo r k StageNOTESA FIELD GUIDE FOR TEACHERS Table of Contents Using the Field Guide......................................................................................................................3 -

Enhancing Recreation, Parks, Tourism Courses: Using Movies As

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DigitalCommons@CalPoly Vol. 9, No. 2. ISSN: 1473-8376 www.heacademy.ac.uk/johlste ACADEMIC PAPER Enhancing recreation, parks and tourism courses: Using movies as teaching tools Marni Goldenberg ([email protected]) Recreation, Parks and Tourism Administration Department, California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo, CA 93407, USA Jason W Lee ([email protected]) Sport Management Program, Department of Leadership, Counseling, and Instructional Technology, University of North Florida, 1 UNF Drive, 57/3200, Jacksonville, FL32224, USA Teresa O’Bannon ([email protected]) Department of Recreation, Parks and Tourism, Radford University, Box 6963, Radford, VA 24142, USA DOI:10.3794/johlste.92.215 ©Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sport and Tourism Education Abstract The use of movies provides educators with a valuable tool for presenting information as learners are able to benefit from the powerful images being presented before them. The purpose of this study was to identify the value of the use of movies as a teaching tool. This was an exploratory study aimed at identifying characteristics of movie use as an educational device in recreation, parks, and tourism classes. In this study, respondents (n = 67) indicated that the use of movies in the classroom was supported, and the findings of this study suggest that most instructors provided advance preparation activities and reflection activities on the use of movies, and their relationship to the curricular topics. Additionally, future considerations regarding using movies as a teaching tool and the educational value associated with purposeful inclusion of movies into curricular efforts are identified.