Orca.Cf.Ac.Uk/114269

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Application Dossier for the Proposed Black Country Global Geopark

Application Dossier For the Proposed Black Country Global Geopark Page 7 Application Dossier For the Proposed Black Country Global Geopark A5 Application contact person The application contact person is Graham Worton. He can be contacted at the address given below. Dudley Museum and Art Gallery Telephone ; 0044 (0) 1384 815575 St James Road Fax; 0044 (0) 1384 815576 Dudley West Midlands Email; [email protected] England DY1 1HP Web Presence http://www.dudley.gov.uk/see-and-do/museums/dudley-museum-art-gallery/ http://www.blackcountrygeopark.org.uk/ and http://geologymatters.org.uk/ B. Geological Heritage B1 General geological description of the proposed Geopark The Black Country is situated in the centre of England adjacent to the city of Birmingham in the West Midlands (Figure. 1 page 2) .The current proposed geopark headquarters is Dudley Museum and Art Gallery which has the office of the geopark coordinator and hosts spectacular geological collections of local fossils. The geological galleries were opened by Charles Lapworth (founder of the Ordovician System) in 1912 and the museum carries out annual programmes of geological activities, exhibitions and events (see accompanying supporting information disc for additional detail). The museum now hosts a Black Country Geopark Project information point where the latest information about activities in the geopark area and information to support a visit to the geopark can be found. Figure. 7 A view across Stone Street Square Dudley to the Geopark Headquarters at Dudley Museum and Art Gallery For its size, the Black Country has some of the most diverse geology anywhere in the world. -

Ludlow, Silurian) Positive Carbon Isotope Excursion in the Type Ludlow Area, Shropshire, England?

At what stratigraphical level is the mid Ludfordian (Ludlow, Silurian) positive carbon isotope excursion in the type Ludlow area, Shropshire, England? DAVID K. LOYDELL & JIØÍ FRÝDA The balance of evidence suggests that the mid Ludfordian positive carbon isotope excursion (CIE) commences in the Ludlow area, England in the uppermost Upper Whitcliffe Formation, with the excursion continuing into at least the Platyschisma Shale Member of the overlying Downton Castle Sandstone Formation. The Ludlow Bone Bed Member, at the base of the Downton Castle Sandstone Formation has previously been considered to be of Přídolí age. Conodont and 13 thelodont evidence, however, are consistent with the mid Ludfordian age proposed here. New δ Corg data are presented from Weir Quarry, W of Ludlow, showing a pronounced positive excursion commencing in the uppermost Upper Whitcliffe Formation, in strata with a palynologically very strong marine influence. Elsewhere in the world, the mid Ludfordian positive CIE is associated with major facies changes indicated shallowing; the lithofacies evidence from the Ludlow area is consistent with this. There appears not to be a major stratigraphical break at the base of the Ludlow Bone Bed Member. • Key words: Silurian, Ludlow, carbon isotopes, conodonts, chitinozoans, thelodonts, stratigraphy. LOYDELL, D.K. & FRÝDA, J. 2011. At what stratigraphical level is the mid Ludfordian (Ludlow, Silurian) positive car- bon isotope excursion in the type Ludlow area, Shropshire, England? Bulletin of Geosciences 86(2), 197–208 (5 figures, 2 tables). Czech Geological Survey, Prague. ISSN 1214-1119. Manuscript received January 17, 2011; accepted in re- vised form March 28, 2011; published online April 13, 2011; issued June 20, 2011. -

Limestone Pavements: Or on Paper Is a Matter for Debate

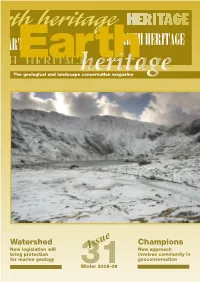

e Watershed ssu Champions New legislation will I New approach bring protection involves community in for marine geology 31 geoconservation Winter 2008-09 People power is the key On other pages Geology and Geodiversity are often daunting subjects for people. Geoconservationists Outcrops – pp 3-5 can gain much wider public support and enthusiasm for the subjects by drawing back Inspirations for education – p6 the technical veil that shrouds them. Education and community working are two of the Champion idea – p8 most effective tools, and reports in Earth Heritage 31 show we are using them adeptly. What better way to protect sites than letting local communities adopt them (p8)? How Exemplary collaboration uncovers better to enthuse and engage children than to create free Powerpoint presentations for new information – p10 their teachers – on imagination-grabbing subjects like Plate Tectonics, the Ice Age, Rock art – Dinosaurs, Volcanoes and Climate Change (p7)? How better to explain the origins of captive or our landscape than through a free, web-based service that integrates cultural, free historical, habitat, visual and geological information in a GIS-based system (p16)? range? – p12 Protection of geological heritage is always at the forefront of our agenda. Big opportunities are provided by the Marine and Coastal Access Act (expected to become Co-ordination in action – p14 law in the summer; p3) and National Indicator 197 (p13). The legal proceedings concerning the Pakefield to Easton Bavents SSSI in Suffolk (p4) have received LANDMAP: Joined-up widespread but sometimes inaccurate media coverage. This landmark case has thinking makes vital potentially massive implications for how we conserve coastal Earth Science SSSI. -

Devonian As a Time of Major Innovation in Plants and Their Communities

1 Back to the Beginnings: The Silurian- 2 Devonian as a Time of Major Innovation 15 3 in Plants and Their Communities 4 Patricia G. Gensel, Ian Glasspool, Robert A. Gastaldo, 5 Milan Libertin, and Jiří Kvaček 6 Abstract Silurian, with the Early Silurian Cooksonia barrandei 31 7 Massive changes in terrestrial paleoecology occurred dur- from central Europe representing the earliest vascular 32 8 ing the Devonian. This period saw the evolution of both plant known, to date. This plant had minute bifurcating 33 9 seed plants (e.g., Elkinsia and Moresnetia), fully lami- aerial axes terminating in expanded sporangia. Dispersed 34 10 nate∗ leaves and wood. Wood evolved independently in microfossils (spores and phytodebris) in continental and 35AU2 11 different plant groups during the Middle Devonian (arbo- coastal marine sediments provide the earliest evidence for 36 12 rescent lycopsids, cladoxylopsids, and progymnosperms) land plants, which are first reported from the Early 37 13 resulting in the evolution of the tree habit at this time Ordovician. 38 14 (Givetian, Gilboa forest, USA) and of various growth and 15 architectural configurations. By the end of the Devonian, 16 30-m-tall trees were distributed worldwide. Prior to the 17 appearance of a tree canopy habit, other early plant groups 15.1 Introduction 39 18 (trimerophytes) that colonized the planet’s landscapes 19 were of smaller stature attaining heights of a few meters Patricia G. Gensel and Milan Libertin 40 20 with a dense, three-dimensional array of thin lateral 21 branches functioning as “leaves”. Laminate leaves, as we We are now approaching the end of our journey to vegetated 41 AU3 22 now know them today, appeared, independently, at differ- landscapes that certainly are unfamiliar even to paleontolo- 42 23 ent times in the Devonian. -

Newsletter No. 266 April 2021

NewsletterNewsletter No.No. 266266 AprilApril 20212021 Contents: Future Programme 2 Committee Other Societies and Events 3 Chairman Editorial 5 Graham Worton Annual General Meeting 6 Vice Chairman Andrew Harrison GeoconservationUK 8 Hon Treasurer Hello from another new BCGS member 9 Alan Clewlow Matt's Maps No.2 - Sedgley Beacon & Hon Secretary Coseley Cutting 9 Position vacant Field Secretary My Involvement with Wren's Nest 13 Andrew Harrison BCGS Poet in Residence, R. M. Francis 16 Meetings Secretary Keith Elder Mike's Musings No.31: Getting a Taste for Geology 16 Newsletter Editor Julie Schroder Social Media To find out more about this image - read on! Peter Purewal Robyn Amos Webmaster John Schroder Other Member Bob Bucki Copy date for the next Newsletter is Tuesday 1 June Newsletter No. 266 The Black Country Geological Society April 2021 Position vacant Andy Harrison, Julie Schroder, Honorary Secretary, Field Secretary, Newsletter Editor, 42 Billesley Lane, Moseley, ☎ [email protected] 07973 330706 Birmingham, B13 9QS. [email protected] ☎ 0121 449 2407 [email protected] For enquiries about field and geoconservation meetings please contact the Field Secretary. To submit items for the Newsletter please contact the Newsletter Editor. For all other business and enquiries please contact the Honorary Secretary. For more information see our website: bcgs.info, YouTube, Twitter: @BCGeoSoc and Facebook. Future Programme Indoor meetings are normally held in the Abbey Room at the Dudley Archives, Tipton Road, Dudley, DY1 4SQ, 7.30 for 8.00 o'clock start unless stated otherwise. The same timing applies to the current programme of online 'Zoom' meetings. Visitors are welcome to attend BCGS events. -

Earth Matters the Newsletter of the Geology Section of the Woolhope Naturalists’Field Club the Geology Section Is an Affiliate Member of the Geologists’ Association

Earth Matters The Newsletter of the Geology Section of the Woolhope Naturalists’Field Club The Geology Section is an Affiliate Member of the Geologists’ Association. No. 7 December 2010 The Woolhope Naturalists’ Field Club is a Registered Charity, No. 521000 MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIRMAN CONTENTS NCE again, I can say that we've had a good year Oand this despite some very wintery weather that Message from the Chairman ........................... 1 set in just when some of us were beginning fieldwork on an EHT programme. However, I want to digress Geology Section Programme .......................... 2 from the Herefordshire scene and look further afield. Last year I recalled Iain Stewart's remarks at the GA Editor’s Note ................................................... 2 Dinner in 2008. Iain gave an up beat and optimistic speech but things seem not to be working out quite Subscriptions ................................................... 2 so well as he anticipated. I refer to the current eco- nomic downturn; to the effects this is already having Annual General Meeting .................................. 2 on geology and geoconservation; and the likely out- come. We in the WGS may not appear to be greatly On-Line Geology Maps from BGS ................. 2 affected, possibly as individuals, but more certainly as a group of like-minded persons with a common ‘A Weekend in West Wales - September 2010’ interest. Unfortunately, this cannot be said for pro- by Gerry Calderbank .............................. 3 fessional geologists. Recent years have seen a steady decline in the universities, with geology departments ‘Meeting Reports, 2009-10’ either closing or the geological content subsumed by Geoff Steel and John Payne ............. 6 into other departments. -

University of Groningen Fish Microfossils from the Upper Silurian

University of Groningen Fish microfossils from the Upper Silurian Öved Sandstone Formation, Skåne, southern Sweden Vergoossen, Johannes Marie Josephus IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2003 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Vergoossen, J. M. J. (2003). Fish microfossils from the Upper Silurian Öved Sandstone Formation, Skåne, southern Sweden. s.n. Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 23-09-2021 123 FISH MICROFOSSILS FROM THE UPPER SILURIAN ÖVED SANDSTONE FORMATION, SKÅNE, SOUTHERN SWEDEN. Chapter 6 Observations on the correlation of microvertebrate faunas from the Upper Silurian Öved Sandstone Formation. Published in: J. Satkunas, J., J. Lazauskiene (Eds.): “The Fifth Baltic Stratigraphic Conference, Basin Stratigraphy - Modern Methods and Problems”, September 22-27, 2002, Vilnius, Lithuania: Extended Abstracts: 222-224. -

Shropshire Building Stone Atlas

STRATEGIC STONE STUDY A Building Stone Atlas of Shropshire Published May 2012 Derived from BGS digital geological mapping at 1:625,000 scale, British Geological Survey © Shropshire Bedrock Geology NERC. All rights reserved Click on this link to visit Shropshire’s geology and its contribution to known building stones, stone structures and building stone quarries (Opens in new window http://maps.bgs.ac.uk/buildingstone?County=Shropshire ) Shropshire Strategic Stone Study 1 Introduction The presence of a wide range of lithologies within an area also meant that several different Many areas of Britain are characterised by their stone types were liable to occur in a single indigenous building stones, for example the building. Nowhere is this better exemplified Jurassic LIMESTONE of the Cotswolds, the than in the Stretton Valley, where a number FLINT of the CHALK downlands of ‘The South- of different lithologies are brought into close East’, the granite of Dartmoor, and the gritstone proximity along the Church Stretton Fault Zone. of ‘The North’. But look at a vernacular St. Laurence’s Church in Church Stretton is a architecture map of Britain and the chances are case in point (see p.3). it will show Shropshire (along with Cheshire to the north and Herefordshire to the south) as “black and white” or timber-framed country. In practice, for pre-mid C19 buildings, stone constructions are more common than timber- framed ones in several parts of the county. This is not the general perception, however, because there is no single characteristic stone. Instead, one sees extensive use of local stone mirroring the considerable variety of different rock types cropping out across the county. -

Archetypally Siluro-Devonian Ichnofauna in the Cowie Formation

Proceedings of the Geologists’ Association 128 (2017) 815–828 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Proceedings of the Geologists’ Association journa l homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/pgeola Archetypally Siluro-Devonian ichnofauna in the Cowie Formation, Scotland: implications for the myriapod fossil record and Highland Boundary Fault Movement Anthony P. Shillito*, Neil S. Davies Department of Earth Sciences, University of Cambridge, Downing Street, Cambridge CB2 3EQ, United Kingdom A R T I C L E I N F O A B S T R A C T Article history: Received 2 March 2017 The Cowie Formation of the Stonehaven Group is the lithostratigraphically oldest unit of the Old Red Received in revised form 4 August 2017 Sandstone in Scotland. A reliable determination of the formation’s age has implications for the arthropod Accepted 7 August 2017 fossil record (as it contains the world’s oldest known fossils of air-breathing myriapoda), the unit’s burial Available online 6 September 2017 history, and constraints on the timing of the movement of the regionally significant Highland Boundary Fault. Previous studies, utilising different dating techniques, have provided conflicting ages for the unit: Keywords: middle Silurian (late Wenlock), based on palynomorph biostratigraphy; or Early Devonian (Lochkovian– Silurian Pragian), from U-Pb dating of tuffs. Here we report a previously undescribed non-marine trace fossil Devonian assemblage that has implications for the age of the Cowie Formation when it is compared with other Non-marine Siluro-Devonian formations worldwide. The trace fossil assemblage is a low diversity ichnofauna of Fluvial Taenidium Arenicolites isp., Taenidium barretti and rare comma-shaped impressions, in addition to sporadic Arenicolites bioturbated layers and sedimentary surface textures of a possible microbial origin. -

English Nature Research Report

Natural Arca: 76. Shropshire Hills Geological Significance: Outstanding (provisional) ~ __ ~ General geological character: The Shropshire I Iills Natural Area is a classic area for geology and contains inany sites of International importance. Many of the pioneering geological investigations were carried out in south Shropshirc and Series names such as Wenlock and 1,udlow define internationally accepted periods of' gcological time. The south-eastern corner of the Natural Area is coincident with the River 'I'eme; from hcrc the area stretches north-westwards encompassing Ludlow, thc Clee Hills, Wcnlock Edge, Longmynd, Stipcrstones, the Shelve Inlicr and a tract of land east of i,ong Mountain and Welshpool. The varied topography is a reflection of the diverse underlying geology. Generally south Shropshire is formed of relatively hard, rcsistant rocks (between 300 to 700 Ma) but the variety of the geology is such that each 'hill ~iiass'has its own distinctive feature, froiii the gaunt crags of the Stiperstoncs and the Longinynd Plateau to the spcclacular ridgc and valc country around Wenlock Edge. Clee I Iills and Stiperstones form the highest ground in the area attaining heights in excess of 530m AOD. 'I'lie geological structure of the Natural Area is dominated by two NG-SW trcnding faults; the Pontesford Linley Fault ('PLP - which borders the Shelve inlier and Imngmynd) and the Church Stretton Fault ('CSF' - which separates the Longmynd from Ordoviciaii-Silurraii strata of thc Caer Caradoc-Wenlock Kdge region). The oldest rocks in thc area are latc I'recambrian (Uriconian) age, approximatcly 600 to 6.50 Ma, and comprise a series of thick lavas (rhyolites, andcsitcs and basalts) and volcanic ashes (tuffs). -

Number 13 March 2016 Price £5.00

Number 13 March 2016 Price £5.00 AGM 2016 May 21st - Alabaster from the Cardiff area Leader: Mike Statham (with Jana Horák & Steve Howe). To comply with our constitution we need to elect (or Meet: 10.30 am, Cardiff Bay Barrage car park, Penarth re-elect) offcers at the 2016 AGM. The key posts are Portway, CF64 1TT, grid ref. ST 190 724. listed below. Tim Palmer would like to stand down This is trip will explore the occurrence and use of alabaster as Field Secretary, so we require nominations for this deposits that Mike has been researching (see article). post. Other offcers are willing to stand again but this This is a joint meeting with the South Wales Geologists’ does not preclude members from standing. If there are Association. more than two candidates for any post we will hold June 18th. - Haverfordwest, Part II. an election at the AGM. Please let me know if you Leaders: Robin Sheldrake, John Shipton & Jana Horák. wish to stand or require any further information. The Meet: 11.00 am in the small car park at the entrance closing date for nominations is 8th April 2016. Please to Fortunes Frolic, on the east bank of the Cleddau send them to ([email protected]). downstream (south) from the railway embankment. Coming from Carmarthen, this is the frst exit left off Current offcers the Salutation Square roundabout (County Hall is the Chair: Dr John Davies second). Secretary: Dr Jana Horak Continuation of the 2014 excursion (see Newsletter 11). Treasurer: Andrew Haycock th Field Recorder: John Shipton July 9 - Neath Abbey (postponed from 2015) Leader: Tim Palmer Field Secretary: vacant Meet: 11.00 at the entrance to the abbey. -

The Building Stones of Ludlow: a Walk Through the Town

ISSN 1750-855X (Print) ISSN 1750-8568 (Online) The building stones of Ludlow: a walk through the town 1 Michael Rosenbaum ROSENBAUM, M.S. (2007). The building stones of Ludlow: a walk through the town. Proceedings of the Shropshire Geological Society, 12, 5-38. The buildings in the centre of Ludlow reveal the geology of south Shropshire, reflecting both the availability of suitable stone and the changing fashions and technologies of using it. This ranges from the local, somewhat friable, grey calcareous siltstone of Whitcliffe, through the stronger yellow, red and purple sandstones of late Silurian age, to the Carboniferous dolerite intrusions of the Clee Hills to the east. A number of glaciers almost met in late Quaternary times, bringing with them a wide variety of sand and gravel, some of which has been employed in the town. Improved bulk transport from Georgian times onwards (canals, then railways and latterly roads) has enabled use to be made of better quality stone sourced from more distant quarries. 1Ludlow, UK. E-mail: [email protected] Geological maps of the area have been available in published form for some time, the earliest 1. GEOLOGICAL SETTING being in 1832 (Wright & Wright). Their The bedrock geology of Ludlow is evolution chart the development of geological predominantly Silurian in age, deposited some science in general as well as knowledge 420 million years ago. The dome-shaped hill of concerning the local structure and stratigraphy Whitcliffe Common that overlooks the town in particular, yet significant uncertainties still (Figure 1), rising into Mortimer Forest to the remain. Copyright restrictions prevent their west, is the result of an upfold in these rocks, reproduction here, but the interested reader is effectively demonstrating an anticline.