Treecreeper Species Focus by Mike Toms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Birds of the Phoenix Park, County Dublin: Results of a Repeat Breeding Bird Survey in 2015

The Birds of the Phoenix Park, County Dublin: Results of a Repeat Breeding Bird Survey in 2015 Prepared by Lesley Lewis, Dick Coombes & Olivia Crowe A report commissioned by the Office of Public Works and prepared by BirdWatch Ireland September 2015 Address for correspondence: BirdWatch Ireland, Unit 20 Block D Bullford Business Campus, Kilcoole, Co. Wicklow. Phone: + 353 1 2819878 Email: [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................................ 9 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................. 10 Methods ....................................................................................................................................................... 10 Survey design ...................................................................................................................................... 10 Field methods ..................................................................................................................................... 11 Data analysis & interpretation ........................................................................................................... 12 Results .......................................................................................................................................................... 12 Species diversity and abundance -

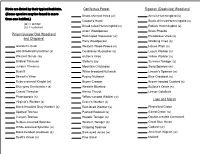

Common Birds of the Prescott Area Nuthatch.Cdr

Birds are listed by their typical habitats. Coniferous Forest Riparian (Creekside) Woodland (Some species may be found in more Sharp-shinned Hawk (w) Anna's Hummingbird (s) than one habitat.) Cooper's Hawk Black-chinned Hummingbird (s) (w) = winter (s) = summer Broad-tailed Hummingbird (s) Rufous Hummingbird (s) Acorn Woodpecker Black Phoebe Pinyon/Juniper/Oak Woodland Red-naped Sapsucker (w) Plumbeous Vireo (s) and Chaparral Hairy Woodpecker Warbling Vireo (s) Gambel's Quail . Western Wood-Pewee (s) House Wren (s) Ash-throated Flycatcher (s) Cordilleran Flycatcher (s) Lucy's Warbler (s) Western Scrub-Jay Hutton's Vireo Yellow Warbler (s) Bridled Titmouse Steller's Jay Summer Tanager (s) Juniper Titmouse . Mountain Chickadee Song Sparrow (w) Bushtit White-breasted Nuthatch Lincoln's Sparrow (w) Bewick's Wren . Pygmy Nuthatch Blue Grosbeak (s) Ruby-crowned Kinglet (w) Brown Creeper Brown-headed Cowbird (s) Blue-gray Gnatcatcher (s) Western Bluebird Bullock's Oriole (s) Crissal Thrasher Hermit Thrush Lesser Goldfinch Phainopepla (s) Yellow-rumped Warbler (w) Lake and Marsh Virginia's Warbler (s) Grace's Warbler (s) Black-throated Gray Warbler (s) Red-faced Warbler (s) Pied-billed Grebe Spotted Towhee Painted Redstart (s) Eared Grebe (w) Canyon Towhee Hepatic Tanager (s) Double-crested Cormorant Rufous-crowned Sparrow Western Tanager (s) Great Blue Heron White-crowned Sparrow (w) Chipping Sparrow Gadwall (w) Black-headed Grosbeak (s) Dark-eyed Junco (w) American Wigeon (w) Scott’s Oriole (s) Pine Siskin Mallard Lake and Marsh (cont.) Varied or Other Habitats Cinnamon Teal (s) Turkey Vulture (s) Common Birds Northern Shoveler (w) Red-tailed Hawk Northern Pintail (w) Rock Pigeon of the Green-winged Teal (w) Eurasian Collared-Dove Prescott Canvasback (w) Mourning Dove Ring-necked Duck (w) Greater Roadrunner Area Lesser Scaup (w) Ladder-backed Woodpecker Bufflehead (w) Northern Flicker Common Merganser (w) Cassin's Kingbird (s) Ruddy Duck (w) Common Raven American Coot Violet-green Swallow (s) . -

Hungary & Transylvania

Although we had many exciting birds, the ‘Bird of the trip’ was Wallcreeper in 2015. (János Oláh) HUNGARY & TRANSYLVANIA 14 – 23 MAY 2015 LEADER: JÁNOS OLÁH Central and Eastern Europe has a great variety of bird species including lots of special ones but at the same time also offers a fantastic variety of different habitats and scenery as well as the long and exciting history of the area. Birdquest has operated tours to Hungary since 1991, being one of the few pioneers to enter the eastern block. The tour itinerary has been changed a few times but nowadays the combination of Hungary and Transylvania seems to be a settled and well established one and offers an amazing list of European birds. This tour is a very good introduction to birders visiting Europe for the first time but also offers some difficult-to-see birds for those who birded the continent before. We had several tour highlights on this recent tour but certainly the displaying Great Bustards, a majestic pair of Eastern Imperial Eagle, the mighty Saker, the handsome Red-footed Falcon, a hunting Peregrine, the shy Capercaillie, the elusive Little Crake and Corncrake, the enigmatic Ural Owl, the declining White-backed Woodpecker, the skulking River and Barred Warblers, a rare Sombre Tit, which was a write-in, the fluty Red-breasted and Collared Flycatchers and the stunning Wallcreeper will be long remembered. We recorded a total of 214 species on this short tour, which is a respectable tally for Europe. Amongst these we had 18 species of raptors, 6 species of owls, 9 species of woodpeckers and 15 species of warblers seen! Our mammal highlight was undoubtedly the superb views of Carpathian Brown Bears of which we saw ten on a single afternoon! 1 BirdQuest Tour Report: Hungary & Transylvania 2015 www.birdquest-tours.com We also had a nice overview of the different habitats of a Carpathian transect from the Great Hungarian Plain through the deciduous woodlands of the Carpathian foothills to the higher conifer-covered mountains. -

PPCO Twist System

A Brown-headed Nuthatch brings food to the nest. Color-coded leg bands enable the authors and their colleagues to discern the curious and potentially complex relationships among the various individuals at Tall Timbers Research Station on the Florida–Georgia line. Photo by © Tara Tanaka. photos by Tara Tanaka Tallahassee, Florida [email protected] 46 BIRDING • FEBRUARY 2016 arblers are gorgeous, jays boisterous, and sparrows elusive, Wbut words like “cute” and “adorable” come to mind when the conversation shifts to Brown-headed Nuthatches. The word “cute” doesn’t appear in the scientifc literature regularly, but science may help to explain its frequent association with nuthatch- es. The large heads and small bodies nuthatches possess have propor- tions similar to those found on young children. Psychologists have found that these proportions conjure up “innate attractive” respons- es among adult humans even when the proportions fall on strange objects (Little 2012). This range-restricted nuthatch associated with southeastern pine- woods has undergone steep declines in recent decades and is listed as a species of special concern in most states in which it breeds (Cox and Widener 2008). The population restricted to Grand Bahama Island appears to be critically endangered (Hayes et al. 2004). Add to these concerns some intriguing biology that includes helpers at the nest, communal winter roosts, seed caching, social grooming, and the use of tools, and you have some scintillating science all bound up in one “cute” and “adorable” package. James -

Best of the Baltic - Bird List - July 2019 Note: *Species Are Listed in Order of First Seeing Them ** H = Heard Only

Best of the Baltic - Bird List - July 2019 Note: *Species are listed in order of first seeing them ** H = Heard Only July 6th 7th 8th 9th 10th 11th 12th 13th 14th 15th 16th 17th Mute Swan Cygnus olor X X X X X X X X Whopper Swan Cygnus cygnus X X X X Greylag Goose Anser anser X X X X X Barnacle Goose Branta leucopsis X X X Tufted Duck Aythya fuligula X X X X Common Eider Somateria mollissima X X X X X X X X Common Goldeneye Bucephala clangula X X X X X X Red-breasted Merganser Mergus serrator X X X X X Great Cormorant Phalacrocorax carbo X X X X X X X X X X Grey Heron Ardea cinerea X X X X X X X X X Western Marsh Harrier Circus aeruginosus X X X X White-tailed Eagle Haliaeetus albicilla X X X X Eurasian Coot Fulica atra X X X X X X X X Eurasian Oystercatcher Haematopus ostralegus X X X X X X X Black-headed Gull Chroicocephalus ridibundus X X X X X X X X X X X X European Herring Gull Larus argentatus X X X X X X X X X X X X Lesser Black-backed Gull Larus fuscus X X X X X X X X X X X X Great Black-backed Gull Larus marinus X X X X X X X X X X X X Common/Mew Gull Larus canus X X X X X X X X X X X X Common Tern Sterna hirundo X X X X X X X X X X X X Arctic Tern Sterna paradisaea X X X X X X X Feral Pigeon ( Rock) Columba livia X X X X X X X X X X X X Common Wood Pigeon Columba palumbus X X X X X X X X X X X Eurasian Collared Dove Streptopelia decaocto X X X Common Swift Apus apus X X X X X X X X X X X X Barn Swallow Hirundo rustica X X X X X X X X X X X Common House Martin Delichon urbicum X X X X X X X X White Wagtail Motacilla alba X X -

The Importance of Landscape Structure for Nest Defence in the Eurasian Treecreeper Certhia Familiaris

Ornis Fennica 84:145–154. 2007 The importance of landscape structure for nest defence in the Eurasian Treecreeper Certhia familiaris Ari Jäntti, Harri Hakkarainen, Markku Kuitunen*, Jukka Suhonen Jäntti, A., Department of Biological and Environmental Science, P. O. Box 35 (YAC), Survontie 9, FI-40014, University of Jyväskylä, Finland Hakkarainen, H., Section of Ecology, Department of Biology, University of Turku, FI- 20014 Turku, Finland Kuitunen, M., Department of Biological and Environmental Science, P.O. Box 35 (YAC), Survontie 9, FI-40014, University of Jyväskylä, Finland. [email protected] (*Cor- responding author) Suhonen, J., Department of Biological and Environmental Science, P. O. Box 35 (YAC), Survontie 9, FI-40014, University of Jyväskylä, Finland. Current address: Section of Ecology, Department of Biology, University of Turku, FI-20014 Turku, Finland Received 19 April 2006, revised 9 August 2007, accepted 20 August 2007 Forest loss and fragmentation induces harmful ecological effects especially for species preferring mature forests. The Eurasian Treecreeper, Certhia familiaris, is highly special- ised in foraging on large tree trunks and can only occasionally forage outside of mature fo- rests. We quantified nest defence behaviour of Treecreeper parents toward a stuffed model of Great Spotted Woodpecker Dendrocopos major in central Finland. We used a Geographical Information System (GIS) to measure the landscape structure within a 200 m radius around the nest. We found that females with more fledged offspring gave alarm calls from farther away from the predator model than did females with fewer fledged off- spring. The alarming distance of females was longer when the forest patch around the nest was larger. -

Downy Woodpecker and White-Breasted Nuthatch Use "Vice" to Open Sunflower Seeds: Is This an Example of Tool Use?

DOWNY WOODPECKER AND WHITE-BREASTED NUTHATCH USE "VICE" TO OPEN SUNFLOWER SEEDS: IS THIS AN EXAMPLE OF TOOL USE? By William E. Davis, Jr. During the past three winters I have watched Downy Woodpeckers and White-breasted Nuthatches using knotholes as "vices" to hold sunflower seeds while shucking them. I have found no direct reference to this behavior for either species, although nuthatches are well-known cachers of food and presumably open cached food items where they are cached. The purpose of this paper is to document this vice-using Behavior and to discuss whether it should Be considered as tool use. On February 2, 1993, I watched a male Downy Woodpecker at my sunflower feeder remove a seed and fly five feet directly to a knothole (hole #1) that was 6.5 feet above the ground in a vertical three-inch stem of the same lilac cluster from which the feeder was suspended. The Downy proceeded to insert the seed into the knothole, which had a hard, flat lower surface (Figure 1), and pound it open and eat the seed. It repeated this procedure five times in three minutes. The woodpecker did not hold the seed with its feet the way chickadees and titmice do when they open sunflower seeds and, in fact, did not touch the seed with its feet at any time. On March 3 I watched the same male Downy (it had a distinctive pattern of red, white, and Black on its nape) make nine trips to hole #1 and sBc trips to a second knothole (hole #2) five feet from the feeder on a nearly horizontal stem 4.5 feet above the ground in the same lilac complex (Figure 2). -

White-Breasted Nuthatch Sitta Carolinensis ILLINOIS RANGE

white-breasted nuthatch Sitta carolinensis Kingdom: Animalia FEATURES Phylum: Chordata The white-breasted nuthatch averages five to six Class: Aves inches in length. It has blue-gray back feathers and Order: Passeriformes white belly feathers. The male has a cap of black feathers while the female has a blue-gray-feathered Family: Sittidae cap. ILLINOIS STATUS common, native BEHAVIORS The white-breasted nuthatch is a common, permanent resident statewide in Illinois. Nesting takes place from April through May. This bird nests in deciduous woodlands in a knothole in a large tree, an old woodpecker hole or a nest box. The nest is placed 15 to 50 feet above the ground. The nest cavity is lined with grasses, hair, rootlets, sticks and other materials. The female builds the nest. She deposits six to nine white eggs with red-brown spots and incubates them for the 12-day incubation period. One brood is raised per year. The white- breasted nuthatch lives in woodlands, parks and orchards. It searches for food by walking down tree trunks head-first. It eats insects, nuts and acorns. ILLINOIS RANGE © Illinois Department of Natural Resources. 2021. Biodiversity of Illinois. Unless otherwise noted, photos and images © Illinois Department of Natural Resources. © Illinois Department of Natural Resources. 2021. Biodiversity of Illinois. Unless otherwise noted, photos and images © Illinois Department of Natural Resources. © Illinois Department of Natural Resources. 2021. Biodiversity of Illinois. Unless otherwise noted, photos and images © Illinois Department of Natural Resources. provided by stevebyland/pond5.com adult Aquatic Habitats bottomland forests Woodland Habitats bottomland forests; coniferous forests; southern Illinois lowlands; upland deciduous forests Prairie and Edge Habitats edge © Illinois Department of Natural Resources. -

Colorado Birds the Colorado Field Ornithologists’ Quarterly

Vol. 50 No. 4 Fall 2016 Colorado Birds The Colorado Field Ornithologists’ Quarterly Stealthy Streptopelias The Hungry Bird—Sun Spiders Separating Brown Creepers Colorado Field Ornithologists PO Box 929, Indian Hills, Colorado 80454 cfobirds.org Colorado Birds (USPS 0446-190) (ISSN 1094-0030) is published quarterly by the Col- orado Field Ornithologists, P.O. Box 929, Indian Hills, CO 80454. Subscriptions are obtained through annual membership dues. Nonprofit postage paid at Louisville, CO. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to Colorado Birds, P.O. Box 929, Indian Hills, CO 80454. Officers and Directors of Colorado Field Ornithologists: Dates indicate end of cur- rent term. An asterisk indicates eligibility for re-election. Terms expire at the annual convention. Officers: President: Doug Faulkner, Arvada, 2017*, [email protected]; Vice Presi- dent: David Gillilan, Littleton, 2017*, [email protected]; Secretary: Chris Owens, Longmont, 2017*, [email protected]; Treasurer: Michael Kiessig, Indian Hills, 2017*, [email protected] Directors: Christy Carello, Golden, 2019; Amber Carver, Littleton, 2018*; Lisa Ed- wards, Palmer Lake, 2017; Ted Floyd, Lafayette, 2017; Gloria Nikolai, Colorado Springs, 2018*; Christian Nunes, Longmont, 2019 Colorado Bird Records Committee: Dates indicate end of current term. An asterisk indicates eligibility to serve another term. Terms expire 12/31. Chair: Mark Peterson, Colorado Springs, 2018*, [email protected] Committee Members: John Drummond, Colorado Springs, 2016; Peter Gent, Boul- der, 2017*; Tony Leukering, Largo, Florida, 2018; Dan Maynard, Denver, 2017*; Bill Schmoker, Longmont, 2016; Kathy Mihm Dunning, Denver, 2018* Past Committee Member: Bill Maynard Colorado Birds Quarterly: Editor: Scott W. Gillihan, [email protected] Staff: Christy Carello, science editor, [email protected]; Debbie Marshall, design and layout, [email protected] Annual Membership Dues (renewable quarterly): General $25; Youth (under 18) $12; Institution $30. -

Thailand Highlights March 9–28, 2019

THAILAND HIGHLIGHTS MARCH 9–28, 2019 Gray Peacock-Pheasant LEADER: DION HOBCROFT LIST COMPILED BY: DION HOBCROFT VICTOR EMANUEL NATURE TOURS, INC. 2525 WALLINGWOOD DRIVE, SUITE 1003 AUSTIN, TEXAS 78746 WWW.VENTBIRD.COM By Dion Hobcroft The stunning male Blue Pitta that came in to one of the wildlife viewing hides at Kaeng Krachan. We returned to the “Land of Smiles” for our annual and as expected very successful tour in what is undoubtedly the most diverse and comfortable country for birding in Southeast Asia. Thailand is fabulous. Up early as is typical, we went to the recently sold off Muang Boran fish ponds—now sadly being drained and filled in. The one surviving pond was still amazing, as we enjoyed great looks at Pallas’s Grasshopper Warbler, Baillon’s Crake, a winter-plumaged Watercock, Black-headed Kingfisher, and a handful of Asian Golden Weavers, although only one male fully colored up. Nearby Bang Poo was packed to the gills with shorebirds, gulls, and fish-eating waterbirds. Amongst the highlights here were Painted Storks, breeding plumaged Greater and Lesser sand-plovers, hundreds of Brown-headed Gulls, primordial Mudskippers, and even more ancient: a mating pair of Siamese Horseshoe Crabs! Beverly spotted the elusive Tiger Shrike coming in to bathe at a sprinkler. A midday stroll around the ruins of the ancient capital of Ayutthya also offered some good birds with Small Minivets, a Eurasian Hoopoe feeding three chicks, and a glowing Coppersmith Barbet creating some “oohs and aahs” from first time Oriental birders, and rightly so. One last stop at a Buddhist temple in limestone hills in Saraburi revealed the Victor Emanuel Nature Tours 2 Thailand Highlights, 2019 highly localized Limestone Wren-Babbler; they were quite timid this year, although finally settled for good looks. -

Multiple Fragmented Habitat-Patch Use in an Urban Breeding Passerine, the Short-Toed Treecreeper

RESEARCH ARTICLE Multiple fragmented habitat-patch use in an urban breeding passerine, the Short-toed Treecreeper Katherine R. S. SnellID*, Rie B. E. Jensen, Troels E. Ortvad, Mikkel Willemoes, Kasper Thorup Center for Macroecology, Evolution and Climate, Natural History Museum of Denmark, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark a1111111111 * [email protected] a1111111111 a1111111111 a1111111111 a1111111111 Abstract Individual responses of wild birds to fragmented habitat have rarely been studied, despite large-scale habitat fragmentation and biodiversity loss resulting from widespread urbanisa- tion. We investigated the spatial ecology of the Short-toed Treecreeper Certhia brachydac- OPEN ACCESS tyla, a tiny, resident, woodland passerine that has recently colonised city parks at the Citation: Snell KRS, Jensen RBE, Ortvad TE, northern extent of its range. High resolution spatiotemporal movements of this obligate tree- Willemoes M, Thorup K (2020) Multiple living species were determined using radio telemetry within the urbanized matrix of city fragmented habitat-patch use in an urban breeding passerine, the Short-toed Treecreeper. PLoS ONE parks in Copenhagen, Denmark. We identified regular edge crossing behaviour, novel in 15(1): e0227731. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal. woodland birds. While low numbers of individuals precluded a comprehensive characterisa- pone.0227731 tion of home range for this population, we were able to describe a consistent behaviour Editor: Jorge RamoÂn LoÂpez-Olvera, Universitat which has consequences for our understanding of animal movement in urban ecosystems. Autònoma de Barcelona, SPAIN We report that treecreepers move freely, and apparently do so regularly, between isolated Received: July 10, 2019 habitat patches. This behaviour is a possible driver of the range expansion in this species Accepted: December 29, 2019 and may contribute to rapid dispersal capabilities in certain avian species, including Short- toed Treecreepers, into northern Europe. -

EUROPEAN BIRDS of CONSERVATION CONCERN Populations, Trends and National Responsibilities

EUROPEAN BIRDS OF CONSERVATION CONCERN Populations, trends and national responsibilities COMPILED BY ANNA STANEVA AND IAN BURFIELD WITH SPONSORSHIP FROM CONTENTS Introduction 4 86 ITALY References 9 89 KOSOVO ALBANIA 10 92 LATVIA ANDORRA 14 95 LIECHTENSTEIN ARMENIA 16 97 LITHUANIA AUSTRIA 19 100 LUXEMBOURG AZERBAIJAN 22 102 MACEDONIA BELARUS 26 105 MALTA BELGIUM 29 107 MOLDOVA BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA 32 110 MONTENEGRO BULGARIA 35 113 NETHERLANDS CROATIA 39 116 NORWAY CYPRUS 42 119 POLAND CZECH REPUBLIC 45 122 PORTUGAL DENMARK 48 125 ROMANIA ESTONIA 51 128 RUSSIA BirdLife Europe and Central Asia is a partnership of 48 national conservation organisations and a leader in bird conservation. Our unique local to global FAROE ISLANDS DENMARK 54 132 SERBIA approach enables us to deliver high impact and long term conservation for the beneit of nature and people. BirdLife Europe and Central Asia is one of FINLAND 56 135 SLOVAKIA the six regional secretariats that compose BirdLife International. Based in Brus- sels, it supports the European and Central Asian Partnership and is present FRANCE 60 138 SLOVENIA in 47 countries including all EU Member States. With more than 4,100 staf in Europe, two million members and tens of thousands of skilled volunteers, GEORGIA 64 141 SPAIN BirdLife Europe and Central Asia, together with its national partners, owns or manages more than 6,000 nature sites totaling 320,000 hectares. GERMANY 67 145 SWEDEN GIBRALTAR UNITED KINGDOM 71 148 SWITZERLAND GREECE 72 151 TURKEY GREENLAND DENMARK 76 155 UKRAINE HUNGARY 78 159 UNITED KINGDOM ICELAND 81 162 European population sizes and trends STICHTING BIRDLIFE EUROPE GRATEFULLY ACKNOWLEDGES FINANCIAL SUPPORT FROM THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION.