The Online Gaming Industry. the Relationship Between Pricing Mechanisms Used by Game Developers and the Online Gaming Communities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Video Games and the Mobilization of Anxiety and Desire

PLAYING THE CRISIS: VIDEO GAMES AND THE MOBILIZATION OF ANXIETY AND DESIRE BY ROBERT MEJIA DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Communications in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2012 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Kent A. Ono, Chair Professor John Nerone Professor Clifford Christians Professor Robert A. Brookey, Northern Illinois University ABSTRACT This is a critical cultural and political economic analysis of the video game as an engine of global anxiety and desire. Attempting to move beyond conventional studies of the video game as a thing-in-itself, relatively self-contained as a textual, ludic, or even technological (in the narrow sense of the word) phenomenon, I propose that gaming has come to operate as an epistemological imperative that extends beyond the site of gaming in itself. Play and pleasure have come to affect sites of culture and the structural formation of various populations beyond those conceived of as belonging to conventional gaming populations: the workplace, consumer experiences, education, warfare, and even the practice of politics itself, amongst other domains. Indeed, the central claim of this dissertation is that the video game operates with the same political and cultural gravity as that ascribed to the prison by Michel Foucault. That is, just as the prison operated as the discursive site wherein the disciplinary imaginary was honed, so too does digital play operate as that discursive site wherein the ludic imperative has emerged. To make this claim, I have had to move beyond the conventional theoretical frameworks utilized in the analysis of video games. -

EA Casual Games Destination Pogo.Com Teams up with Playfirst to Serve up Diner Dash Family Style to Consumers

EA Casual Games Destination Pogo.com Teams up with PlayFirst to Serve up Diner Dash Family Style to Consumers Pogo.com Lends Community and Multiplayer Expertise to Breakthrough Bestseller Diner Dash REDWOOD CITY, Calif., Nov 21, 2008 (BUSINESS WIRE) -- Ditch your desk job and serve up some grub!Electronic Arts Inc. (NASDAQ:ERTS) today announced a collaborative partnership between Pogo.com(TM) and PlayFirst(R) to create a brand new multiplayer Diner Dash(R) experience with downloadable gameDiner Dash Family Style. The game will take the breakthrough best seller Diner Dash and add in community and multiplayer features to allow fans to experience the game in a new social environment. Diner Dash Family Style allows players to play alongside friends and family, chat, and participate in group challenges while helping fan-favorite Flo(TM) grow her fledgling diner into a five-star restaurant. Diner Dash has been a No. 1 hit across major online game portals, mobile and retail, as well as a popular handheld title now including iPhone, since its debut in late 2004. The original game, developed by the award-winning independent studio Gamelab, is now a multi-million dollar brand, spanning multiple sequels and brand extension spinoffs based on the DinerTown (TM) story world. Features: ● Play through 5 restaurants and 50 levels for hours of fresh, fun gameplay. ● 5 different customer types with different personalities to keep players on their toes. ● Players can build their restaurant empire in career mode or see how long they can serve customers in endless mode. ● NEW! Chat with friends and family while connected to the internet. -

10Th IAA FINALISTS ANNOUNCED

10th Annual Interactive Achievement Awards Finalists GAME TITLE PUBLISHER DEVELOPER CREDITS Outstanding Achievement in Animation ANIMATION DIRECTOR LEAD ANIMATOR Gears of War Microsoft Game Studios Epic Games Aaron Herzog & Jay Hosfelt Jerry O'Flaherty Daxter Sony Computer Entertainment ReadyatDawn Art Director: Ru Weerasuriya Jerome de Menou Lego Star Wars II: The Original Trilogy LucasArts Traveller's Tales Jeremy Pardon Jeremy Pardon Rayman Raving Rabbids Ubisoft Ubisoft Montpellier Patrick Bodard Patrick Bodard Fight Night Round 3 Electronic Arts EA Sports Alan Cruz Andy Konieczny Outstanding Achievement in Art Direction VISUAL ART DIRECTOR TECHNICAL ART DIRECTOR Gears of War Microsoft Game Studios Epic Games Jerry O'Flaherty Chris Perna Final Fantasy XII Square Enix Square Enix Akihiko Yoshida Hideo Minaba Call of Duty 3 Activison Treyarch Treyarch Treyarch Tom Clancy's Rainbow Six: Vegas Ubisoft Ubisoft Montreal Olivier Leonardi Jeffrey Giles Viva Piñata Microsoft Game Studios Rare Outstanding Achievement in Soundtrack MUSIC SUPERVISOR Guitar Hero 2 Activision/Red Octane Harmonix Eric Brosius SingStar Rocks! Sony Computer Entertainment SCE London Studio Alex Hackford & Sergio Pimentel FIFA 07 Electronic Arts Electronic Arts Canada Joe Nickolls Marc Ecko's Getting Up Atari The Collective Marc Ecko, Sean "Diddy" Combs Scarface Sierra Entertainment Radical Entertainment Sound Director: Rob Bridgett Outstanding Achievement in Original Music Composition COMPOSER Call of Duty 3 Activison Treyarch Joel Goldsmith LocoRoco Sony Computer -

Winter 2007 Casual Connect Magazine

Winter 2007 casual connect magazine magazine Casual Connect Magazine Playtime, Anytime MSN Games (games.msn.com) hosts more than 13 million players every month. With more than 300 games, MSN Games offers fun and interactive gameplay through free casual single-player and multiplayer games, downloadable games, and premium multiplayer games. Included are titles for all interests, such as word and trivia, puzzlers, action and adventure titles, along with a multitude of card and board games. Our goal is to bring you the ultimate portable gaming experience, whether you’re playing alone or against your friends. Microsoft Casual Games develops, Xbox Live Arcade (xbox.com/livearcade) is your publishes, and distributes web-based destination for endless hours of fun and addictive play! and download games in every major Xbox Live Arcade brings it all to you through Xbox Live, the premier online gaming casual game genre (puzzle, word, card and entertainment network for the Xbox 360 system. More than 18 million Xbox Live and arcade). On a monthly basis, MCG Arcade games have already been downloaded since the launch of the Xbox 360 in reaches more than 120 million global November 2005, garnering accolades from the industry, press and consumers alike. players; that’s more than a third of the Tune in to Xbox Live Arcade every Wednesday around the world for new releases, U.S. population! new game add-ons, and other exciting news and content. There’s something for everyone! Download, try and play now! Download Fun. Anytime. Anywhere. Microsoft Casual Games offers more than 400 games via MSN® Games, Windows Live™ Messenger, Windows Live Messenger Windows® OS Games, and Xbox (msngames.com/messenger) has a 3000 Live® Arcade, providing the ultimate growing base of 200 million users worldwide. -

View / Open Ada02-Casua-Ana-2013

2/18/2021 Casual Games, Time Management, and the Work of Affect - Ada New Media ISSUE NO. 2 Casual Games, Time Management, and the Work of Affect Aubrey Anable Casual games are stupid and they are taking over our lives. This is what a recent New York Times Magazine article concluded. Sam Anderson, the article’s author, writes, “Tetris and its offspring (Angry Birds, Bejeweled, Fruit Ninja, etc.) have colonized our pockets and our brains and shifted the entire economic model of the video-game industry. Today we are living, for better and worse, in a world of stupid games.” [1] The industry classification of “casual games” encompasses several genres—digital puzzle, word, and card games such as Candy Crush Saga, Words with Friends, or Solitaire, and also time management and social games such as Diner Dash and Farmville. These very different games share some basic similarities: they have simple graphics and mechanics, they are usually browser or app-based, and they are free or cost very little to play. Most importantly though, casual games are designed to be played in short bursts of five to ten minutes and then set aside. As such, what makes a game “casual” is that it functions in the ambiguous time and space between the myriad tasks we do on digital devices; between work and domestic obligations; between solitary play and social gaming; and between attention and distraction. Anderson continues, Stupid games…are rarely occasions in themselves. They are designed to push their way through the cracks of other occasions. We play them incidentally, ambivalently, compulsively, almost accidentally. -

2008‐2009 Casual Games White Paper

2008‐2009 Casual Games White Paper A Project of the Casual Games SIG of the IGDA Find out more at www.igda.org/casual Contents Contents .......................................................................................................................................... 2 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 6 Understanding Casual Games ......................................................................................................... 8 The Market for Casual Games ..................................................................................................... 8 Overview of Casual Game Business Models .............................................................................. 10 The Casual Game Audience ....................................................................................................... 14 Global Design Principles ............................................................................................................ 16 Art Style ..................................................................................................................................... 26 Audio in Casual Games .............................................................................................................. 32 Are Writers Needed For Casual Games? ................................................................................... 39 Characters and Narrative ......................................................................................................... -

Nominees Announced for Second Annual Gamehouse Great Game Awards

Nominees Announced for Second Annual GameHouse Great Game Awards ● Winners to be announced at July 19th Awards Ceremony ● Voting for new Players Choice category open through end of June at GameHouse.com ● All voters will be entered to win an all-expense-paid trip to awards show in Seattle SEATTLE - June 18, 2010 - GameHouse®, a division of RealNetworks®, Inc. (Nasdaq: RNWK), today announced the nominees for the second annual GameHouse Great Game Awards™ (GG's). GameHouse introduced the GG's in 2009 as a way to showcase the most talented and creative casual games developers in the industry. Winners of the second annual Great Game Awards will be announced July 19 during an exclusive event held at Experience Music Project in Seattle. Media Sponsors TechFlash and Gamezebo are partnering with GameHouse to present the 2010 GG's, and the judging panel includes representatives from leading independent developers across the casual games industry. The 2010 GG's will feature a new category, Game of the Year - Player's Choice. Voting is open to the public at GameHouse.com/promotions during the month of June, and one lucky voter will be selected at random to win a trip for two to the Great Game Awards ceremony in Seattle on July 19 to present the Player's Choice Award to the winning developer. The winner and their guest will enjoy airfare and hotel accommodations, passes to Casual Connect, the premiere casual games industry event scheduled for July 20 - 22, a $500 cash prize, a $500 donation to their favorite local charity and a one-year complimentary FunPass - GameHouse.com's premium casual games subscription product. -

Getting in the Game

www.nycfuture.org MAY 2008 Getting in the Game The number of companies creating video games in the five boroughs has spiked in recent years, but New York is well behind several other cities in the race to cultivate this fast-growing part of the entertainment industry CONTENTS IntroductIon 3 the number of companies creating video games in the five boroughs has spiked in recent years, but new York this report was written by tara colton and edited by is well behind several other cities in the race to cultivate Jonathan Bowles and david Jason Fischer. roy Abir pro- this fast-growing part of the entertainment industry vided additional research. General support for city Futures is provided by Bernard tHE BIG PIcturE 7 F. and Alva B. Gimbel Foundation, Booth Ferris Founda- once a niche industry marketing to kids and teenagers, tion, deutsche Bank, the F.B. Heron Foundation, Fund for video games are beginning to rival music and movies in popularity and revenues the city of new York, Salesforce Foundation, the Scher- man Foundation, Inc., and unitarian universalist Veatch Program at Shelter rock. noVIcE PLAYEr 8 new York city’s video game sector has enjoyed robust the center for an urban Future is a new York city-based growth in recent years, but remains modest overall think tank dedicated to independent, fact-based research about critical issues affecting new York’s future, including economic development, workforce development, higher orGAnIZEd KAoS 11 education and the arts. For more information or to sign up for our monthly e-mail bulletin, visit www.nycfuture.org. -

Games As Services Final Report

UNIVERSITY OF TAMPERE DEPARTMENT OF INFORMATION STUDIES AND INTERACTIVE MEDIA Games as Services Final Report Sotamaa, Olli & Karppi, Tero (toim.) 2010 Research Reports 2 ISSN 1799-2141 http://www.trim.fi ISBN 978-951-44-8167-3 GAMES AS SERVICES 2 Contents Introduction 3 by Olli Sotamaa RISE OF A SERVICE PARADIGM 1. Understanding the Range of Player Services 10 by Jaakko Stenros & Olli Sotamaa 2. Digital Distribution of Games: the Player’s Perspective 22 by Saara Toivonen & Olli Sotamaa RETHINKING PLAY AND PLAYERS 3. Console Gaming, Player Production and Agency 35 by Olli Sotamaa 4. Internet Connections: Rethinking the Video Game Console Experience 50 by Tero Karppi 5. Methodological Observations From Behind the Decks 56 by Tero Karppi & Olli Sotamaa 6. Achievement Unlocked: Rethinking Gaming Capital 73 by Olli Sotamaa TRANSFORMATIONS IN BUSINESS AND DESIGN 7. Ten Questions for Games Businesses: Rethinking Customer Relationships 83 by Kai Kuikkaniemi, Marko Turpeinen, Kai Huotari & Lassi Seppälä 8. Motivations for C2C Word-of-Mouth Communication During Online Service Use 95 by Kai Huotari 9. Casual Games and Expanded Game Experiences: Design Point of View 105 by Annakaisa Kultima 10. Use of Camera in Mobile Games and Playful Applications 123 by Lassi Seppälä CONTENTS GAMES AS SERVICES 3 Olli Sotamaa Introduction by Olli Sotamaa In May 2010, Bill Mooney laid out the foundations of game studio Zynga’s methods for game development. Mooney is the general manager of FarmVille, the most popular computer game in the world (over 80 million monthly active users in May 2010) and there- fore his insights should not be underestimated. -

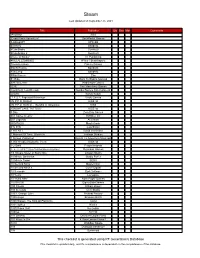

This Checklist Is Generated Using RF Generation's Database This Checklist Is Updated Daily, and It's Completeness Is Dependent on the Completeness of the Database

Steam Last Updated on September 25, 2021 Title Publisher Qty Box Man Comments !AnyWay! SGS !Dead Pixels Adventure! DackPostal Games !LABrpgUP! UPandQ #Archery Bandello #CuteSnake Sunrise9 #CuteSnake 2 Sunrise9 #Have A Sticker VT Publishing #KILLALLZOMBIES 8Floor / Beatshapers #monstercakes Paleno Games #SelfieTennis Bandello #SkiJump Bandello #WarGames Eko $1 Ride Back To Basics Gaming √Letter Kadokawa Games .EXE Two Man Army Games .hack//G.U. Last Recode Bandai Namco Entertainment .projekt Kyrylo Kuzyk .T.E.S.T: Expected Behaviour Veslo Games //N.P.P.D. RUSH// KISS ltd //N.P.P.D. RUSH// - The Milk of Ultraviolet KISS //SNOWFLAKE TATTOO// KISS ltd 0 Day Zero Day Games 001 Game Creator SoftWeir Inc 007 Legends Activision 0RBITALIS Mastertronic 0°N 0°W Colorfiction 1 HIT KILL David Vecchione 1 Moment Of Time: Silentville Jetdogs Studios 1 Screen Platformer Return To Adventure Mountain 1,000 Heads Among the Trees KISS ltd 1-2-Swift Pitaya Network 1... 2... 3... KICK IT! (Drop That Beat Like an Ugly Baby) Dejobaan Games 1/4 Square Meter of Starry Sky Lingtan Studio 10 Minute Barbarian Studio Puffer 10 Minute Tower SEGA 10 Second Ninja Mastertronic 10 Second Ninja X Curve Digital 10 Seconds Zynk Software 10 Years Lionsgate 10 Years After Rock Paper Games 10,000,000 EightyEightGames 100 Chests William Brown 100 Seconds Cien Studio 100% Orange Juice Fruitbat Factory 1000 Amps Brandon Brizzi 1000 Stages: The King Of Platforms ltaoist 1001 Spikes Nicalis 100ft Robot Golf No Goblin 100nya .M.Y.W. 101 Secrets Devolver Digital Films 101 Ways to Die 4 Door Lemon Vision 1 1010 WalkBoy Studio 103 Dystopia Interactive 10k Dynamoid This checklist is generated using RF Generation's Database This checklist is updated daily, and it's completeness is dependent on the completeness of the database. -

Casual Games Market Report 2007 Business and Art of Games for Everyone

Casual Games Market Report 2007 Business and art of games for everyone Cover Illustration from Zen of Sudoku © 2006 Unknown Worlds © 2007 Casual Games Association. See last section for full copyright, trademark and important disclosure information. Table of Contents Welcome Letter from the Director All About Casual 3 What are Casual Games? 5 Online Consumer Profile It has been an exciting year for casual games—not only are more and more people playing, but casual games have become the subject of mainstream news articles and large media companies have become interested in the space with more fervor The Art of Casual than ever. The buzz is not surprising, of course. Many following the industry have known for some time that more people play casual games than any other type of video game. Now in 2007, this fact has become widespread knowledge. In addition, 7 History of Casual Games: 1972 - Present the industry has started to attract new platforms, studios and publishers. What was once an industry centered around PC and 9 Online Content Trends online web games has grown over the past couple of years into emerging casual areas, such as the Xbox LIVE Arcade and the Wii. Inside Casual Right now, the market signs are good for casual games. Luckily the industry has remained stable due in part to casual 19 State of the Industry games being available on a wide range of platforms with the most successful business models encouraging high quality and 22 Casual Game Designers innovative game content. 23 Casual Content Creation The connected casual games industry is a “multi billion dollar industry,” as you will see in detail later in this report – but what 24 How Development Works does that really mean? Ultimately, projections on the total industry size are of little use other than pleasant conversations with 25 Global Market Opportunities relatives. -

Keeping the Promise of Casual Games

Character Cash or Financial Fictions THE ART AND BUSINESS OF STORY DEVELOPMENT IN CASUAL GAMES Kenny Shea Dinkin VP & Creative Director [email protected] Casual Games Summit / Game Developers Conference 08 February 2008 Who am I ? Kenny Shea Dinkin VP and Executive Producer/Creative Director, PlayFirst Inc. • Run PlayFirst’s portfolio of casual, downloadable games like the Diner Dash line, Chocolatier 1 & 2, The Dream Chronicles, Dress Shop Hop, The NightShift Code,, Mystery of Shark Island, Trijinx, Oasis, Plantasia, Doggie Dash, Wedding Dash … What is PlayFirst? What are we gonna talk about today ? I. The Vaudeville Prophecy and “The Promise of Casual Games” Why Casual games have the potential to be the leader in exploring the delivery of narrative in games and unlocking the mass market. II. The Michelangelo Dilemma and the challenge of story integration Why and where we are failing to deliver on the promise. III. The Authenticity Trap and new business models. Why good stories and compelling characters may help us bridge the gap between try/buy and new roads to monetization. Why me? •Former Creative Director at Learning Company/Broderbund overseeing design on a premiere portfolio of interactive brands like Reader Rabbit, ClueFinders, Carmen Sandiego, Oregon Trail, Scooby Doo, more. •12+ years designing/overseeing design on games for non-gamers. • IGDA white paper section contributor on Story and Narrative Nightshift Code 2 Diner Dash and the World of Flo I. The Vaudeville Prophecy and “The Promise of Casual Games” Why Casual games have the potential to be the leader in exploring the delivery of narrative in games and unlocking the mass market.