Republic of Niger

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Région De Maradi: Département De Guidan Roumdji

Région de Maradi: Département de Guidan Roumdji Légende Dakoro Ville de Maradi Localité Route principale Mayahi Cours d'eau Guidan Jibi Lac Guidan Tanko Guidan Roumji Département de Guidam Roumdji Twansala Kaloum Route secondaire Doumana Ara Nahatchi Tekwalou Guidan Bizo Doumana Gober Zoumba Kouroungoussa Katouma Gidan KognaoAlbawa Dan Ganga Garin Chala Koudoumous Mekerfi Boussarague Guidan Barmou Doumana Serkin Fawa Modi Ala Serki Tambari Kankan Mala Kouloum Boutey Kongare Alforma Sahin Daka Oubandiada Alfari Gono Nakaora Tamakiera Wanike Malaba Guidan Zaga Dogon Farou Gaoude TambariKatsari Dan Sara Guidan BotieRoundouna Gangala Dan Madatchi Kaellabi Kwagani Kankari Serkin Sae Dan Baochi Katere Moussa Zango Barhe Sarkaki Guidan Malam Gouni Madara Tambarawa Zodey Dadeo Dan Gali Dan Toudou Malamawa Malam Djibo Serkin Achi Dan Malam Maygije Gidan Dombo Karoussa MaykiMakai Chadakori Goulbin KabaDan Nani Kongare Oubandawaki Chala Gadambo Guidan Aska Kankali Takalmawa Guidan Karou Boukoulou Guidan Malam Mayguije Dan Kade Garin AkaoDan Farou Dan Malam Chagalawa Alfourtouk Guidan Roumdji Dan Madatchi Dan Tourke Gidan Nagidi Dan MairiKourouma Guidan MayaBarago Dan Koulou Allah Kabani Garin Maychanou Garin Jari Kandoussa Dan Koyla Kiemro Koagoni TamroroKaola Alhadji Dango Kotoumbi Tchakire Guidan Ara Guigale Guidan Zaourami Batekoliawa Chadakori Awa Kansara Garin KoutoubouKoukanahandi Karandia Garin Nouhou Guidam Roumji Koumchi Sofoa Berni Garin Gado Ara Dan Baraouka Djenia Amalka Kaymou Guidan Achi Tamindawa Kalgo Guidan Kalgo Kouka Dan Wada Bongounji -

Satisfaction Des Besoins En Eau Potable Des Populations Rurales Dans La Région De Tahoua Par La Mobilisation Des Eaux Des Aquifères Profonds

DIRECTION DES ETUDES ET DES SERVICES « PHV-Tahoua » ACADEMIQUES Thème : ETUDE DE REALISATION DES ADDUCTIONS D’EAU POTABLE SIMPLIFIEE DANS LE CADRE DU PROJET D’HYDRAULIQUE VILLAGEOISE DE TAHOUA. PROPOSITION DES VARIANTES TECHNIQUES POUVANT CONTRIBUER A L’OPTIMISATION DES COUTS DE REVIENT DES OUVRAGES. MEMOIRE POUR L’OBTENTION DE DIPLOME DE MASTER D’INGENIERIE EN EAU ET ENVIRONNEMENT Présenté par : KONDO ABDOU Travaux dirigés par : Mr .DENIS ZOUNGRANA Enseignant-UTER GVEA Mr. SALEY OUMAROU Bureau d’études CEH-SIDI MEMBRES DU JURY juin, 2009 Satisfaction des besoins en eau potable des populations rurales dans la région de Tahoua par la mobilisation des eaux des aquifères profonds 2 i. DEDICACES A mon défunt père et A ma défunte mère, qu’ALLAH les couvre de Sa Grâce et de Sa Miséricorde, A ma femme, à qui je souhaite encore une santé de fer et une très longue vie et qui m’a encouragé pour terminer cette étude A mes enfants Hassane, Osseyna et Salima qui ont supporté mon absence durant des années A mon ami et promotionnel Souley O . Maidawa qui s’est occupé de ma famille durant mon absence A Mrs .Aminou M .K et Amadou A. responsables du cabinet AGECRHAU qui m’ont soutenu financièrement et professionnellement A tous les Enseignants (es) et Professeurs qui ont eu à m’enseigner durant tout mon cursus scolaire, depuis le CI A la fondation du 2iE et son personnel A Mr .Mahaman Koubou , qui m’a appuyé durant toute la durée de mes études . A tous ceux et toutes celles qui m’ont soutenu directement ou indirectement A vous tous que j’ai cités, ce travail de mémoire est dédié 3 ii. -

Arrêt N° 012/11/CCT/ME Du 1Er Avril 2011 LE CONSEIL

REPUBLIQUE DU NIGER Fraternité – Travail – Progrès CONSEIL CONSTITUTIONNEL DE TRANSITION Arrêt n° 012/11/CCT/ME du 1er Avril 2011 Le Conseil Constitutionnel de Transition statuant en matière électorale en son audience publique du premier avril deux mil onze tenue au Palais dudit Conseil, a rendu l’arrêt dont la teneur suit : LE CONSEIL Vu la Constitution ; Vu la proclamation du 18 février 2010 ; Vu l’ordonnance n° 2010-01 du 22 février 2010 modifiée portant organisation des pouvoirs publics pendant la période de transition ; Vu l’ordonnance n° 2010-096 du 28 décembre 2010 portant code électoral ; Vu l’ordonnance n° 2010-038 du 12 juin 2010 portant composition, attributions, fonctionnement et procédure à suivre devant le Conseil Constitutionnel de Transition ; Vu le décret n° 2011-121/PCSRD/MISD/AR du 23 février 2011 portant convocation du corps électoral pour le deuxième tour de l’élection présidentielle ; Vu l’arrêt n° 01/10/CCT/ME du 23 novembre 2010 portant validation des candidatures aux élections présidentielles de 2011 ; Vu l’arrêt n° 006/11/CCT/ME du 22 février 2011 portant validation et proclamation des résultats définitifs du scrutin présidentiel 1er tour du 31 janvier 2011 ; Vu la lettre n° 557/P/CENI du 17 mars 2011 du Président de la Commission Electorale Nationale Indépendante transmettant les résultats globaux provisoires du scrutin présidentiel 2ème tour, aux fins de validation et proclamation des résultats définitifs ; Vu l’ordonnance n° 028/PCCT du 17 mars 2011 de Madame le Président du Conseil constitutionnel portant -

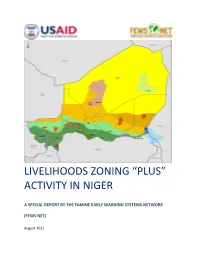

Livelihoods Zoning “Plus” Activity in Niger

LIVELIHOODS ZONING “PLUS” ACTIVITY IN NIGER A SPECIAL REPORT BY THE FAMINE EARLY WARNING SYSTEMS NETWORK (FEWS NET) August 2011 Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Methodology ................................................................................................................................................. 4 National Livelihoods Zones Map ................................................................................................................... 6 Livelihoods Highlights ................................................................................................................................... 7 National Seasonal Calendar .......................................................................................................................... 9 Rural Livelihood Zones Descriptions ........................................................................................................... 11 Zone 1: Northeast Oases: Dates, Salt and Trade ................................................................................... 11 Zone 2: Aïr Massif Irrigated Gardening ................................................................................................ 14 Zone 3 : Transhumant and Nomad Pastoralism .................................................................................... 17 Zone 4: Agropastoral Belt ..................................................................................................................... -

The Inception of a Political Movement for MHM in Niger

The Joint Programme on Gender, Hygiene and Sanitation INFORMATION LETTER NO. 10, JANUARY-JUNE 2017 The inception of a political movement for MHM in Niger Niger has made considerable progress in recent months in promoting sanitation and hygiene for women and girls. Two workshops were held in December by the Ministry of Water and Sanitation, 2016 and February 2017 on the which was chosen by the participants to integration of menstrual hygiene in play a leading role in mobilising decision- national policies and strategies. In his makers on MHM. opening statement, the Minister of Water and Sanitation of Niger, His Excellency Improving cooperation Nigerien Minister Barmou Salifou at the opening of the February 2017 policy workshop. ©REJEA Barmou Salifou, said it was time to break The growing number of actors for MHM the silence on the importance of good must work out how to cooperate more menstrual hygiene and commit to work in effectively. During the two workshops, It is time to favour of integration (of MHM) in public participants agreed to work with elected policies. officials, including those outside Niamey break the silence. (in regions, departments and towns) and Barmou Salifou, High-level officials from various ministries to involve the network of elected female Minister of Water and Sanitation of Niger (water and sanitation, health, education, officials in the implementation of MHM environment) took part in activities led activities. Continued on page 2 Women waiting before the Lab celebrated at Tillabéri Region in Niger, last August 2016 ©WSSCC /Javier Acebal THE JOINT PROGRAMME ON GENDER, HYGIENE AND SANITATION Continued from page 1 They also decided to set up an intersectoral platform to exchange information and created a joint working group from various sectoral ministries to compile an information sheet and promote menstrual hygiene, in order to help integrate MHM in public policies. -

BROCHURE Dainformation SUR LA Décentralisation AU NIGER

REPUBLIQUE DU NIGER MINISTERE DE L’INTERIEUR, DE LA SECURITE PUBLIQUE, DE LA DECENTRALISATION ET DES AFFAIRES COUTUMIERES ET RELIGIEUSES DIRECTION GENERALE DE LA DECENTRALISATION ET DES COLLECTIVITES TERRITORIALES brochure d’INFORMATION SUR LA DÉCENTRALISATION AU NIGER Edition 2015 Imprimerie ALBARKA - Niamey-NIGER Tél. +227 20 72 33 17/38 - 105 - REPUBLIQUE DU NIGER MINISTERE DE L’INTERIEUR, DE LA SECURITE PUBLIQUE, DE LA DECENTRALISATION ET DES AFFAIRES COUTUMIERES ET RELIGIEUSES DIRECTION GENERALE DE LA DECENTRALISATION ET DES COLLECTIVITES TERRITORIALES brochure d’INFORMATION SUR LA DÉCENTRALISATION AU NIGER Edition 2015 - 1 - - 2 - SOMMAIRE Liste des sigles .......................................................................................................... 4 Avant propos ............................................................................................................. 5 Première partie : Généralités sur la Décentralisation au Niger ......................................................... 7 Deuxième partie : Des élections municipales et régionales ............................................................. 21 Troisième partie : A la découverte de la Commune ......................................................................... 25 Quatrième partie : A la découverte de la Région .............................................................................. 53 Cinquième partie : Ressources et autonomie de gestion des collectivités ........................................ 65 Sixième partie : Stratégies et outils -

Stratégie De Développement Rural

République du Niger Comité Interministériel de Pilotage de la Stratégie de Développement Rural Secrétariat Exécutif de la SDR Stratégie de Développement Rural ETUDE POUR LA MISE EN PLACE D’UN DISPOSITIF INTEGRE D’APPUI CONSEIL POUR LE DEVELOPPEMENT RURAL AU NIGER VOLET DIAGNOSTIC DU RÔLE DES ORGANISATIONS PAYSANNES (OP) DANS LE DISPOSITIF ACTUEL D’APPUI CONSEIL Rapport provisoire Juillet 2008 Bureau Nigérien d’Etudes et de Conseil (BUNEC - S.A.R.L.) SOCIÉTÉ À RESPONSABILITÉ LIMITÉE AU CAPITAL DE 10.600.000 FCFA 970, Boulevard Mali Béro-km-2 - BP 13.249 Niamey – NIGER Tél : +227733821 Email : [email protected] Site Internet : www.bunec.com 1 AVERTISSEMENTS A moins que le contexte ne requière une interprétation différente, les termes ci-dessous utilisés dans le rapport ont les significations suivantes : Organisation Rurale (OR) : Toutes les structures organisées en milieu rural si elles sont constituées essentiellement des populations rurales Organisation Paysanne ou Organisation des Producteurs (OP) : Toutes les organisations rurales à caractère associatif jouissant de la personnalité morale (coopératives, groupements, associations ainsi que leurs structures de représentation). Organisation ou structure faîtière: Tout regroupement des OP notamment les Union Fédération, Confédération, associations, réseaux et cadre de concertation. Union : Regroupement d’au moins 2 OP de base, c’est le 1er niveau de structuration des OP. Fédération : C’est un 2ème niveau de structuration des OP qui regroupe très souvent les Unions. Confédération : Regroupement les fédérations des Unions, c’est le 3ème niveau de structuration des OP Membre des OP : Personnes physiques ou morales adhérents à une OP Adhérents : Personnes physiques membres des OP Promoteurs ou structures d’appui ou partenaires : ce sont les services de l’Etat, ONG, Projet ou autres institutions qui apportent des appuis conseil, technique ou financier aux OP. -

I – Prospecting Licence Exploration Licence

Procedure for acquisition of Granting of the exploration licence. I – Prospecting Licence exploration licence One (1) year validity The permit is granted in a maximum of one Granted by the Director of Mines Submission of application to the month from coming into force of the Mining Confers first refusal right for the licence to Minister of Mines and Energy in triple agreement. get exploration licence. copies including: Statues, balance sheet and III-Mining licence accounting statement of the Granting procedure of the prospecting Validity of ten (10) years, renewable licence applicant for the last year ; Minerals for which the licence is for five (5) years until complete requested ; exploitation of deposit; Submission of the application in triple Area of the perimeter requested, Granted by decree of the Council of copies to the Director of Mines, it administrative regions; Ministers; includes: Limits of the perimeter and Confers exclusive right. Statues, balance sheet and accounting geographic points on a 1/200,000 Procedure for acquisition of statement of the applicant for the last year; scale map ; mining licence Object of the prospecting ; Duration of the licence ; General projected working program; Technical and financial capacities; Commitment to submit a half-yearly Commitment on investment; Production of positive feasibility report to the Director of Mines; General program and works study on the perimeter of the Receipt of fees payment schedule; exploration permit; Application evaluation; Copy of any joint-venture Registration of mining company in Granting of the prospecting authorization Receipt of fees payment; terms of Niger Law as specified in the within 30 days from the deposit of the Mining agreement proposal; mining agreement; application date. -

Région De Agadez Pour Usage Humanitaire Uniquement CARTE DE REFERENCE Date De Production : 21 Mars 2018

Niger - Région de Agadez Pour Usage Humanitaire Uniquement CARTE DE REFERENCE Date de production : 21 mars 2018 6°0'0"E 9°0'0"E 12°0'0"E 15°0'0"E Libye Madama " N " 0 ' 0 ° 2 Tchad 2 Djado Inazawa " "Yaba "Tchounouk " Djado ""Tchibarkatene Tchibarkatene " Chirfa Algérie "Sara "Touaret Dan Timni Iferouane " Tchingalene " Tchingalene Tamjit Iferouane " " Tamjit "Amji Temet Taghajit " " Bilma "Siguidine "Intikikitene N " 0 Ourarene Ii " ' 0 " ° 0 Ourarene I 2 "Assamaka Ezazaw Gougaram " Farzakat Tchirawayen " " Dirkou Azatraya Abarkot " Mama Manat " Arlit " "Korira "Tezirzait Tadek Est Tadek Ouest " " "Ifiniyan Tchin Dagar"a " Tch" inkawkane " Etaghass " " " Anouzaghaghane Arso " Taghwaye Tchiwalmass Et Agreroum Agharouss " " Oumaratt " " " " " " " Izayakan Tadekilt " "Aneye Elaglag Ii " Lateye Amizigra " " " " Iferouane Agly Eknawan Emitchouma " " Fares Tchouwoye " " Tagze " "" " " Issawan Tamat " " " Ebidni Tchifirissene " Souloufiet " Awey Kisse " " "Aboughalel Tamgak Tanout-Mollat " Infara " " " Arlit Ezil " Ebourkoum Temedrissou " Ichifa Tadaous " " " Achinouma Gabo Anouzagagan " "Ingall " Wizat " " " " " " " Maghet " Anigaran " "Elabag Zanawey " Temelait Argui Boukoki Ii (Est) " " "" Inwourigan Arakam """ " Carre Nouveau Marche " " " " " " Tamazan I " " " " "" Iko " Barara "" Ziguilaw " Taghait Kerdema Akokan Carre C " Tiliya " Eghighi " " Tirgaf " Eggar " " " " Tagmert " " Tassilim Agorass N'Imi" Iguintar Azangneriss " " " Arag 1 Tarainat " " Agalal " " Agheytom " Chimaindour " " " Madawela Madawela " Wiye " " " " Tamilik Mayat 2 -

Final Evaluation of Imagine Project

FINAL EVALUATION OF IMAGINE PROJECT Consultants: Abagi Sidi Idriss Issa Bawa Mme Abdoul Baki Baraka Adamou Niamey, August 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................................... 6 A. Context of the evaluation .................................................................................................................... 6 B. Objectives of the evaluation................................................................................................................ 6 C. Methodology of the evaluation............................................................................................................ 7 II. PRESENTATION OF THE IMAGINE PROJECT ........................................................................ 8 A. Technical elaboration of the project.................................................................................................... 8 B. Relevance of the IMAGINE project.................................................................................................... 9 C. Project Funding Arrangements.......................................................................................................... 10 III. PROJECT REALIZATIONS AND EFFECTIVENESS............................................................... 12 A. Increase access to education, particularly for girls............................................................................ 12 1) The realizations of component n°1 .............................................................................................. -

«Fichier Electoral Biométrique Au Niger»

«Fichier Electoral Biométrique au Niger» DIFEB, le 16 Août 2019 SOMMAIRE CEV Plan de déploiement Détails Zone 1 Détails Zone 2 Avantages/Limites CEV Centre d’Enrôlement et de Vote CEV: Centre d’Enrôlement et de Vote Notion apparue avec l’introduction de la Biométrie dans le système électoral nigérien. ▪ Avec l’utilisation de matériels sensible (fragile et lourd), difficile de faire de maison en maison pour un recensement, C’est l’emplacement physique où se rendront les populations pour leur inscription sur la Liste Electorale Biométrique (LEB) dans une localité donnée. Pour ne pas désorienter les gens, le CEV servira aussi de lieu de vote pour les élections à venir. Ainsi, le CEV contiendra un ou plusieurs bureaux de vote selon le nombre de personnes enrôlées dans le centre et conformément aux dispositions de création de bureaux de vote (Art 79 code électoral) COLLECTE DES INFORMATIONS SUR LES CEV Création d’une fiche d’identification de CEV; Formation des acteurs locaux (maire ou son représentant, responsable d’état civil) pour le remplissage de la fiche; Remplissage des fiches dans les communes (maire ou son représentant, responsable d’état civil et 3 personnes ressources); Centralisation et traitement des fiches par commune; Validation des CEV avec les acteurs locaux (Traitement des erreurs sur place) Liste définitive par commune NOMBRE DE CEV PAR REGION Région Nombre de CEV AGADEZ 765 TAHOUA 3372 DOSSO 2398 TILLABERY 3742 18 400 DIFFA 912 MARADI 3241 ZINDER 3788 NIAMEY 182 ETRANGER 247 TOTAL 18 647 Plan de Déploiement Plan de Déploiement couvrir tous les 18 647 CEV : Sur une superficie de 1 267 000 km2 Avec une population électorale attendue de 9 751 462 Et 3 500 kits (3000 kits fixes et 500 tablettes) ❖ KIT = Valise d’enrôlement constitués de plusieurs composants (PC ou Tablette, lecteur d’empreintes digitales, appareil photo, capteur de signature, scanner, etc…) Le pays est divisé en 2 zones d’intervention (4 régions chacune) et chaque région en 5 aires. -

Evaluation of the Niger Education and Community Strengthening Progrm

Evaluation of the Niger Education and Community Strengthening Program Design Report First Draft: February 14, 2013 Revised: August 23, 2013 Errata Corrected: October 1, 2014 Revised: June 6, 2016 Emilie Bagby Evan Borkum Anca Dumitrescu Matt Sloan Mathematica Reference Number: Evaluation of the Niger 40038.300 Education and Community Submitted to: Strengthening Program Millennium Challenge Corporation 1099 14th Street NW Suite 700Washington, DC 20005-3550 Design Report Project Officer: Carolyn Perrin First Draft: February 14, 2013 Revised: August 23, 2013 Submitted by: Errata Corrected: October 1, 2014 Mathematica Policy Research 1100 1st Street, NE Revised: June 6, 2016 12th Floor Washington, DC 20002-4221 Telephone: (202) 484-9220 Emilie Bagby Facsimile: (202) 863-1763 Evan Borkum Project Director: Matt Sloan Anca Dumitrescu Matt Sloan Design Report Mathematica Policy Research CONTENTS A. Introduction ............................................................................................................... 1 B. Research Questions ................................................................................................. 3 C. Evaluation Design ..................................................................................................... 5 1. Overview of Design ............................................................................................ 5 2. NECS Random Assignment ............................................................................... 7 3. Estimating Overall Impacts ..............................................................................