Two Children of the Foothills Elizabeth Harrison

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Harry Potter

December 2015 Community Expresses Support for Library in Renewal of 10-Year Dedicated 11.1-Mill Tax Now Library Staff Members Roll Control, I want to say thank you to Up Their Sleeves to Implement voters for supporting the Library and 10-Year Plan recognizing the importance of the Library throughout the Parish and n October 24, one voter after the impact it makes every day on the Oanother at precincts across the young and the old alike. I also want Parish marked individual ballots to thank the EBR Library PAC and YES for the Library’s dedicated tax Patrons of the Public Library (POPL) renewal of 11.1 mills on Election Day. for all their support in passing this The Library tax was renewed by more dedicated tax renewal,” said Kizzy than 58.4 percent of the voters tonight. A. Payton, President of the Library The Library is almost entirely Board of Control. supported by the 10-year dedicated “The Library is critical to this property tax, which was up for community, and this renewal allows renewal this year after being renewed On election night, (left to right) East us to in turn support you with state- previously in 1995 and 2005. Almost Baton Rouge Parish Library Board of of-the art facilities, cutting-edge all the Library System’s budget is Control President Kizzy A. Payton, technology, free WiFi and computer funded by this tax renewal. member Kathy Wascom and Vice use, engaging meeting and study The reasons the tax was renewed President Jason Jacob helped update a space, books, classes, programs, are simple: the Library provides map monitoring the “winning districts” online resources and so much more,” resources and services community passing the Library tax renewal. -

The Rogues Proposal Free

FREE THE ROGUES PROPOSAL PDF Jennifer Haymore | 416 pages | 19 Nov 2013 | Little, Brown & Company | 9781455523375 | English | New York, United States Rogues (comics) - Wikipedia This loose criminal The Rogues Proposal refer to themselves as the Roguesdisdaining the use of The Rogues Proposal term "supervillain" or "supercriminal". The Rogues, compared to similar collections of supervillains in the DC Universeare an unusually social group, maintaining a code of The Rogues Proposal as The Rogues Proposal as high standards for acceptance. No Rogue may inherit another Rogue's identity a "legacy" villain, for example while the original still lives. Also, simply acquiring a former Rogue's costume, gear, or abilities is not sufficient to become a Rogue, even if the previous Rogue is already dead. The Rogues Proposal do not kill anyone unless it is absolutely necessary. Additionally, the Rogues refrain from drug usage. Although they tend to lack the wider name recognition of the villains who oppose Batman and Supermanthe enemies of the Flash form a distinctive rogues gallery through their unique blend of colorful costumes, diverse powers, and unusual abilities. They lack any one defining element or theme between them, and have no significant ambitions in their criminal enterprises beyond relatively petty robberies. The Rogues are referenced by Barry Allen to have previously been defeated by him and disbanded. A year prior, Captain Cold, Heat Wave, the Mirror Master Sam Scudder againand the Weather Wizard underwent a procedure at an unknown facility that would merge them with their weapons, giving them superpowers. The procedure went awry and exploded. Cold's sister Lisa, who was also at the facility, was caught in the explosion. -

MABA Newsletter Index January 1980 Thru December 2020

MABA Newsletter Index January 1980 thru December 2020 This searchable index will help you locate what year & issue projects and information have been published in the MABA newsletter, The Upsetter, over the past 40 years. It is divided into 37 categories to help you quickly narrow your search or use the PDF “Find” function. Sometimes an article fits into more than one category so it has been placed under the most obvious location, while occasionally being placed under multiple categories. The demonstrator, not necessarily the author of the article, is listed to identify and/or credit the source of the information. Please forward any comments or corrections to the MABA newsletter editors. Dates of newsletters that were not available for inclusion in this index: May – June 1995; November – December 1995; If anyone has copies of these newsletters and could pass on the contents so they can be added to this index, it would be greatly appreciated. Look over the entire index and note the categories that have a lot of entries, and those that have only a few. Have you been to a demonstration; solved a problem; completed a project; made a jig, fixture or tool that you’d want to share with others? Would a write-up help other smiths get their projects done without going through the problems you’ve had? Where do your blacksmithing interests lie? Are there many entries in your area of interest? Would an article about your area of interest create some excitement about the subject? Please consider contributing an article to the Upsetter and passing along your experience and information to the MABA membership. -

Sep CUSTOMER ORDER FORM

OrdErS PREVIEWS world.com duE th 18 FeB 2013 Sep COMIC THE SHOP’S pISpISRReeVV eeWW CATALOG CUSTOMER ORDER FORM CUSTOMER 601 7 Sep13 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 8/8/2013 9:49:07 AM Available only DOCTOR WHO: “THE NAME OF from your local THE DOCTOR” BLACK T-SHIRT comic shop! Preorder now! GODZILLA: “KING OF THANOS: THE SIMPSONS: THE MONSTERS” “INFINITY INDEED” “COMIC BOOK GUY GREEN T-SHIRT BLACK T-SHIRT COVER” BLUE T-SHIRT Preorder now! Preorder now! Preorder now! 9 Sep 13 COF Apparel Shirt Ad.indd 1 8/8/2013 9:54:50 AM Sledgehammer ’44: blaCk SCienCe #1 lightning War #1 image ComiCS dark horSe ComiCS harleY QUinn #0 dC ComiCS Star WarS: Umbral #1 daWn of the Jedi— image ComiCS forCe War #1 dark horSe ComiCS Wraith: WelCome to ChriStmaSland #1 idW PUbliShing BATMAN #25 CATAClYSm: the dC ComiCS ULTIMATES’ laSt STAND #1 marvel ComiCS Sept13 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 8/8/2013 2:53:56 PM Featured Items COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Shifter Volume 1 HC l AnomAly Productions llc The Joyners In 3D HC l ArchAiA EntErtAinmEnt llc All-New Soulfire #1 l AsPEn mlt inc Caligula Volume 2 TP l AvAtAr PrEss inc Shahrazad #1 l Big dog ink Protocol #1 l Boom! studios Adventure Time Original Graphic Novel Volume 2: Pixel Princesses l Boom! studios 1 Ash & the Army of Darkness #1 l d. E./dynAmitE EntErtAinmEnt 1 Noir #1 l d. E./dynAmitE EntErtAinmEnt Legends of Red Sonja #1 l d. E./dynAmitE EntErtAinmEnt Maria M. -

Round 13: Tossups

Bergen Academies Spring Quizbowl Tournament II [BASQT II] Written by David Song, Simon Seal, Ryan Murphy, Caleb Shi, Mollie Bakal, John Ferrante, Marvin Yu, Michael Gleyzer, Derek Lin, and Nathan Tang, Bergen County Academies; Zachary Stier, Princeton University; Rebecca Rosenthal, Swarthmore College. Special thanks to Jon Pinyan. Round 13: Tossups 1. After his arrival in the Grand Isle, one character notices that his wife is badly sunburnt despite going for a swim at the start of this novel. Doctor Mandelet asks if the main character has been associating herself with “pseudo-intellectual women” after her husband expresses his concerns about her. Even though he is in (*) Mexico, Robert Lebrun is longed for by the main character, who regrets nearly being seduced by Alcee Arobin and is concerned for her fidelity to Leonce. For ten points, name this 1899 novel about Edna Pontellier written by Kate Chopin. ANSWER: The Awakening 2. This virus has a roughly-spherical envelope with proteins gp41 and gp120 on the outside, and produces 9 genomic products with just a 9.2 kilobyte genome. A consequence of this virus was initially referred to as GRID because rare conditions such as (*) Kaposi's sarcoma and Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia began occurring in large numbers in drug users and gay men. This retrovirus can be transmitted via bodily fluids and infects CD4+ T cells. For ten points, name this virus which causes Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. ANSWER: Human Immunodeficiency Virus (do not prompt on AIDS) 3. Severus and Maximin, not Constantine, were the benefactors of one of these events at Nicomedia in 305. -

The Presidents of the United States of America II Mp3, Flac, Wma

The Presidents Of The United States Of America II mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: II Country: Europe Released: 1996 Style: Alternative Rock, Pop Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1993 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1961 mb WMA version RAR size: 1792 mb Rating: 4.1 Votes: 157 Other Formats: RA APE MMF MP2 MP3 DXD AAC Tracklist Hide Credits 1 Ladies And Gentlemen Part I 1:37 2 Lunatic To Love 2:57 3 Volcano 2:58 4 Mach 5 3:16 5 Twig 2:37 6 Bug City 3:05 7 Bath Of Fire 3:02 8 Japan 2:34 9 Tiki God 2:53 10 L.I.P. 3:20 Froggie 11 3:10 Guitar – Mark Sandman 12 Toob Amplifier 1:21 13 Supermodel 2:49 14 Tremelo Blooz 2:51 15 Mach 5 (Live) 3:40 16 Tiki Lounge God 3:11 17 Back Porch (Live) 3:34 18 Puffy Little Shoes 5:00 19 Ladies And Gentlemen Part II 3:12 Credits Co-producer – Craig Montgomery Engineer – Craig Montgomery Mastered By – Wally Traugott Mixed By – Jerry Finn Notes Recorded at Bad Animals and Studio Lithio, Seattle. Japanese Edition contains 5 bonus tracks. These are the numbers: 8, 14-17 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year The Presidents Of The United C 67577 II (LP, Album) Columbia C 67577 US 1996 States Of America The Presidents Of The United II (CD, Album + 485092 9 Columbia 485092 9 Australia 1996 States Of America CD + Ltd) The Presidents Of The United CT 67577 II (Cass, Album) Columbia CT 67577 US 1996 States Of America The Presidents Of The United 485092.4 II (Cass, Album) Columbia 485092.4 Malaysia 1996 States Of America The Presidents Of The United CT 67577 II (Cass, Album) Columbia CT 67577 Canada 1996 States Of America Related Music albums to II by The Presidents Of The United States Of America 1. -

Love and the Bible Setting the Stage for the Search

Love and the Bible Robin Calamaio - Copyright 2003 - Edit 2019 freelygive-n.com If you think love is an important topic to Christianity, you owe it to yourself, and the world around you, to learn God's teaching on this subject. It is amazing how confused the teaching is on this vital topic. You are about to embark on a fascinating study, and like all correct Bible understandings, it is tremendously liberating. Love. This seems like an important subject in Christianity. One could even contend it is a core element of the Christian faith. After all, the first commandment is the requirement to love God with all of one's heart, mind, soul and strength (Mk 12:30). The second commandment requires us to love our neighbor as our self (Mk 12:31). This “love” requirement covers all our vital relationships - toward self, neighbor and Creator! But the centrality of this “love doctrine” extends even further. The Bible states that love fulfills the Law (Ro 13:8-10 and Gal 5:14). So, all the legal requirements of the Law of God are fulfilled by love? It is evidently made up of something that has the ability to even satisfy the requirements the entire Old Testament theocracy. This is worth thought, investigation and inquiry. So, ... what is love? If we are to fulfill these commands, we need some kind of definition. How else can we know if we are meeting His requirements? Before proceeding, I want you to write down your definition of “love.” Nobody will ever know what you write down unless you decide to share it. -

Creative Christmas Crafts Homemade Craft Ideas for a Special Christmas

12/10/2015 Free Craft Instructions - How to Make a German Paper Star (Froebel Star) Page 1 Home Spring & Easter Crafts Summer Crafts Autumn Crafts Christmas & Winter Crafts Paper Crafts Textile Crafts Wood Crafts General Crafts Craft Patterns & Templates Craft Tutorials Kids Crafts Greeting Cards Picture Gallery Latest Craft Additions Sitemap Links Contact Privacy Policy and Cookies Creative Christmas Crafts Homemade Craft Ideas For A Special Christmas. Get CrazyForCrafts Now! Illustrated Craft Tutorial - How to Make a German Paper Star - “Froebel Stern” - Page 1 This star can also be made with metallic paper strips which adds an elegant touch to it. This tutorial is using 4 different colors of paper to make the steps easier to follow. AdChoices ► Learn German ► Origami Paper Craft ► 3D Origami Christmas Star 1. Cut 4 strips of paper measuring all measuring 1 x 45 cm or 1.5 cm x 50 cm or 2.5 x 90 cm. This particular width and length was 1.5 x 50 cm and will make stars measuring approximately 4x4 cm. Fold each strip in half longwise. Cut the ends to a point. That makes the weaving easier in the later steps. http://www.craftideas.info/html/german_star_instructions.html 1/6 12/10/2015 Free Craft Instructions - How to Make a German Paper Star (Froebel Star) Page 1 2. Insert each strip within the next in each direction. When correctly done they should pull together and hold each other in place. 3. This is now how the star looks. 4. Fold top left strip down. 5. Fold the bottom left strip to the right. -

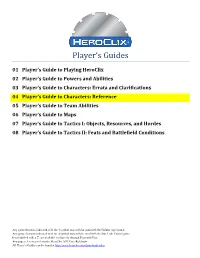

Characters – Reference Guide

Player’s Guides 01 Player’s Guide to Playing HeroClix 02 Player’s Guide to Powers and Abilities 03 Player’s Guide to Characters: Errata and Clarifications 04 Player’s Guide to Characters: Reference 05 Player’s Guide to Team Abilities 06 Player’s Guide to Maps 07 Player’s Guide to Tactics I: Objects, Resources, and Hordes 08 Player’s Guide to Tactics II: Feats and Battlefield Conditions Any game elements indicated with the † symbol may only be used with the Golden Age format. Any game elements indicated with the ‡ symbol may only be used with the Star Trek: Tactics game. Items labeled with a are available exclusively through Print-and-Play. Any page references refer to the HeroClix 2013 Core Rulebook. All Player’s Guides can be found at http://www.heroclix.com/downloads/rules Table of Contents Legion of Super Heroes† .................................................................................................................................................................................................. 1 Avengers† ......................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Justice League† ................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 4 Mutations and Monsters† ................................................................................................................................................................................................ -

Graphic Novels and Comics in the Classroom

Graphic Novels and Comics in the Classroom This page intentionally left blank Graphic Novels and Comics in the Classroom Essays on the Educational Power of Sequential Art Edited by CARRYE KAY SYMA and ROBERT G. WEINER Foreword by ROBERT V. S MITH Afterword by MEL GIBSON McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Jefferson, North Carolina, and London LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Graphic novels and comics in the classroom : essays on the educational power of sequential art / edited by Carrye Kay Syma and Robert G. Weiner ; foreword by Robert V. Smith ; afterword by Mel Gibson. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-7864-5913-1 softcover : acid free paper 1. Comic books, strips, etc., in education. 2. Graphic novels in education. I. Syma, Carrye Kay, editor of compilation. II. Weiner, Robert G., 1966– editor of compilation. LB1044.9.C59G73 2013 371.33—dc23 2013010027 BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE © 2013 Carrye Kay Syma and Robert G. Weiner. All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Cover illustrations—clockwise from upper left: “Thimble Theatre” comic strip panel, E.C. Segar, 1921; superhero © 2013 Digitalvision; female fire spirit © 2013 Antonis; zombie © 2013 Aaron Rutten; anime eye © 2013 Hemera; man in office © 2013 Dorling Kindersley Manufactured in the United States of America McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640 www.mcfarlandpub.com Acknowledgments The editors would like to thank Dr. -

Czech Contributions to the Progress of Nebraska

Czech Contributions to the Progress of Nebraska Editor Vladimir Kucera Co-Editor Alfred Novacek Venovano ceskym pionyrum Nebrasky, hrdinnym budovatelum americkeho Zapadu, kteri tak podstatne prispeli politickemu, kulturnimu, nabozenskemu, hosopodarskemu, zemedelskemu a socialnimu pokroku tohoto statu Dedicated to the first Czech pioneers who contributed so much to the political, cultural, religious, economical, agricultural and social progress of this state Published for the Bicentennial of the United States of America 1976 Copyright by Vladimir Kucera Alfred Novacek Illustrated by Dixie Nejedly THE GREAT PRAIRIE By Vladimir Kucera The golden disk of the setting sun slowly descends toward the horizon of this boundless expanse, and changes it into thousands of strange, ever changing pictures which cannot be comprehended by the eye nor described by the pen. The Great Prairie burns in the blood-red luster of sunset, which with full intensity, illuminates this unique theatre of nature. Here the wildness of arid desert blends with the smoother view of full green land mixed with raw, sandy stretches and scattered islands of trees tormented by the hot rays of the summer sun and lashed by the blizzards of severe winters. This country is open to the view. Surrounded by a level or slightly undulated plateau, it is a hopelessly infinite panorama of flatness on which are etched shining paths of streams framed by bushes and trees until finally the sight merges with a far away haze suggestive of the ramparts of mountain ranges. The most unforgettable moment on the prairie is the sunset. The rich variety of colors, thoughts and feelings creates memories of daybreak and nightfall on the prairie which will live forever in the mind. -

English Language Books

THE CRÈCHE, A SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY ENGLISH LANGUAGE SOURCES Abrams, Richard and Hutchinson, Warner A. An Illustrated Life of Jesus New York: Wings Books, 1982 (many paintings of the Nativity) Acker, Helen “The Bronze Doors of Ghiberti” A Christmas Gallery, pp. 42-46 Minneapolis: Augsburg Publishing House, 1970 Allen, Charles L. and Wallis, Charles L When Christmas Came to Bethlehem Westwood, New Jersey: Fleming H. Revell, c.1963 (“…unique character studies…” of some of the participants in the manger scene) “An Adobe All Aglow” Country Sampler West. December 1993, pp. 34-39 (Christmas decorating with nacimientos) Araki, Chiyo Origami for Christmas Tokyo: Kodansha International, 1986 (Nativity scene is one of 34 origami creations) Arnaud, Linda The Artful Christmas. Holiday Menus & Festive Collectibles Photography, Michel Arnaud Design & Art Direction, Joel Avirom New York: Stewart, Tabori & Chang, 2002 (Nativities: pp. 14-15, 18-21, 26-27, 142) El arte tradicional del Nacimiento Artes de Mexico, Revista libro numero 81, Ano 2006 Mexico D.F.: Artes de Mexico, noviembre de 2006 (“The Traditional Art of the Nativity Scene” – A complete English version, pages 81-96) “Artistry and Art of Christmas” Italy Italy Magazine, Year V, No. 9, November, 1987, p. 42 Aspectos de las fiestas navideñas en México: Galería Universitaria Aristos, noviembre 1981-febrero 1982 (Aspects of Christmas Celebrations in Mexico: Galería Universitaria Aristos, November 1981-February 1982) Text in Spanish, English, French México: Coordinación de Humanidades, Centro de Investigación y Servicios Museológicos, 1981 Awalt, Barbe and Rhetts, Paul Charlie Carrillo: Tradition & Soul – Tradición y Alma Albuquerque: LPD Press, 1995 (biography of a southwestern santero) Awalt, Barbe and Rhetts, Paul Our Saints Among Us/ Nuestros Santos entre Nosotros – 400 Years of New Mexican Devotional Art With an essay by Thomas J.