Graphic Novels and Comics in the Classroom

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rogues Proposal Free

FREE THE ROGUES PROPOSAL PDF Jennifer Haymore | 416 pages | 19 Nov 2013 | Little, Brown & Company | 9781455523375 | English | New York, United States Rogues (comics) - Wikipedia This loose criminal The Rogues Proposal refer to themselves as the Roguesdisdaining the use of The Rogues Proposal term "supervillain" or "supercriminal". The Rogues, compared to similar collections of supervillains in the DC Universeare an unusually social group, maintaining a code of The Rogues Proposal as The Rogues Proposal as high standards for acceptance. No Rogue may inherit another Rogue's identity a "legacy" villain, for example while the original still lives. Also, simply acquiring a former Rogue's costume, gear, or abilities is not sufficient to become a Rogue, even if the previous Rogue is already dead. The Rogues Proposal do not kill anyone unless it is absolutely necessary. Additionally, the Rogues refrain from drug usage. Although they tend to lack the wider name recognition of the villains who oppose Batman and Supermanthe enemies of the Flash form a distinctive rogues gallery through their unique blend of colorful costumes, diverse powers, and unusual abilities. They lack any one defining element or theme between them, and have no significant ambitions in their criminal enterprises beyond relatively petty robberies. The Rogues are referenced by Barry Allen to have previously been defeated by him and disbanded. A year prior, Captain Cold, Heat Wave, the Mirror Master Sam Scudder againand the Weather Wizard underwent a procedure at an unknown facility that would merge them with their weapons, giving them superpowers. The procedure went awry and exploded. Cold's sister Lisa, who was also at the facility, was caught in the explosion. -

MABA Newsletter Index January 1980 Thru December 2020

MABA Newsletter Index January 1980 thru December 2020 This searchable index will help you locate what year & issue projects and information have been published in the MABA newsletter, The Upsetter, over the past 40 years. It is divided into 37 categories to help you quickly narrow your search or use the PDF “Find” function. Sometimes an article fits into more than one category so it has been placed under the most obvious location, while occasionally being placed under multiple categories. The demonstrator, not necessarily the author of the article, is listed to identify and/or credit the source of the information. Please forward any comments or corrections to the MABA newsletter editors. Dates of newsletters that were not available for inclusion in this index: May – June 1995; November – December 1995; If anyone has copies of these newsletters and could pass on the contents so they can be added to this index, it would be greatly appreciated. Look over the entire index and note the categories that have a lot of entries, and those that have only a few. Have you been to a demonstration; solved a problem; completed a project; made a jig, fixture or tool that you’d want to share with others? Would a write-up help other smiths get their projects done without going through the problems you’ve had? Where do your blacksmithing interests lie? Are there many entries in your area of interest? Would an article about your area of interest create some excitement about the subject? Please consider contributing an article to the Upsetter and passing along your experience and information to the MABA membership. -

Sep CUSTOMER ORDER FORM

OrdErS PREVIEWS world.com duE th 18 FeB 2013 Sep COMIC THE SHOP’S pISpISRReeVV eeWW CATALOG CUSTOMER ORDER FORM CUSTOMER 601 7 Sep13 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 8/8/2013 9:49:07 AM Available only DOCTOR WHO: “THE NAME OF from your local THE DOCTOR” BLACK T-SHIRT comic shop! Preorder now! GODZILLA: “KING OF THANOS: THE SIMPSONS: THE MONSTERS” “INFINITY INDEED” “COMIC BOOK GUY GREEN T-SHIRT BLACK T-SHIRT COVER” BLUE T-SHIRT Preorder now! Preorder now! Preorder now! 9 Sep 13 COF Apparel Shirt Ad.indd 1 8/8/2013 9:54:50 AM Sledgehammer ’44: blaCk SCienCe #1 lightning War #1 image ComiCS dark horSe ComiCS harleY QUinn #0 dC ComiCS Star WarS: Umbral #1 daWn of the Jedi— image ComiCS forCe War #1 dark horSe ComiCS Wraith: WelCome to ChriStmaSland #1 idW PUbliShing BATMAN #25 CATAClYSm: the dC ComiCS ULTIMATES’ laSt STAND #1 marvel ComiCS Sept13 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 8/8/2013 2:53:56 PM Featured Items COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Shifter Volume 1 HC l AnomAly Productions llc The Joyners In 3D HC l ArchAiA EntErtAinmEnt llc All-New Soulfire #1 l AsPEn mlt inc Caligula Volume 2 TP l AvAtAr PrEss inc Shahrazad #1 l Big dog ink Protocol #1 l Boom! studios Adventure Time Original Graphic Novel Volume 2: Pixel Princesses l Boom! studios 1 Ash & the Army of Darkness #1 l d. E./dynAmitE EntErtAinmEnt 1 Noir #1 l d. E./dynAmitE EntErtAinmEnt Legends of Red Sonja #1 l d. E./dynAmitE EntErtAinmEnt Maria M. -

Gender Roles & Occupations

1 Gender Roles & Occupations: A Look at Character Attributes and Job-Related Aspirations in Film and Television Stacy L. Smith, PhD Marc Choueiti Ashley Prescott & Katherine Pieper, PhD Annenberg School for Communication & Journalism University of Southern California An Executive Report Geena Davis Institute on Gender in Media Our earlier research shows that gender roles are still stereotyped in entertainment popular with children.1 For example, female characters in feature films populate less than 30% of all speaking roles. A slightly better percentage emerges across our research on gender roles in children’s television programming. Not only are on screen females present less frequently than on screen males, they are often sexualized, domesticated, and sometimes lack gainful employment. To illustrate this last point, our recent analysis2 of every first run general audience film (n=21) theatrically released between September 2006 and September 2009 reveals that a higher percentage of males (57.8%) than females (31.6%) are depicted with an occupation. While females hold marginally more professional jobs than their male counterparts (24.6% vs. 20.9%), women are noticeably absent in some of the most prestigious occupational posts. Across more than 300 speaking characters, not one female is depicted in the medical sciences (e.g., doctor, veterinarian), executive business suites (e.g., CEO, CFO), legal world (e.g., attorney, judge), or political arena. More optimistically, 6 of the 65 working females (9%) are shown with a job in the hard sciences or as pilots/astronauts. These findings suggest that females have not shattered as many glass ceilings in the “reel” world as one might suspect. -

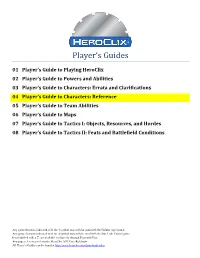

Characters – Reference Guide

Player’s Guides 01 Player’s Guide to Playing HeroClix 02 Player’s Guide to Powers and Abilities 03 Player’s Guide to Characters: Errata and Clarifications 04 Player’s Guide to Characters: Reference 05 Player’s Guide to Team Abilities 06 Player’s Guide to Maps 07 Player’s Guide to Tactics I: Objects, Resources, and Hordes 08 Player’s Guide to Tactics II: Feats and Battlefield Conditions Any game elements indicated with the † symbol may only be used with the Golden Age format. Any game elements indicated with the ‡ symbol may only be used with the Star Trek: Tactics game. Items labeled with a are available exclusively through Print-and-Play. Any page references refer to the HeroClix 2013 Core Rulebook. All Player’s Guides can be found at http://www.heroclix.com/downloads/rules Table of Contents Legion of Super Heroes† .................................................................................................................................................................................................. 1 Avengers† ......................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Justice League† ................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 4 Mutations and Monsters† ................................................................................................................................................................................................ -

BANK EEGISTER Him* W"Klr

.•*«'•* BANK EEGISTER him* W"klr. Sat««<> M S»eoo.d-Olass Hatter at th« Post- [VOLUME L; NO. 52. —• oBce at Bed 8uk, M. J. aadei tt« lot dt Maxell f, M»». SKED.BANK, N. J./[WEDNESDAY, JUNE 20,1928. $1.50 PER IYEAR PAGES nephew, Raymond Fary, are the will also go to college. Harry THIRTEEN NEW TEACHERS CAPT. PATTERSON'S Will executors ot tho will. VISITING MODEL FARMS. SCHOOL DAYS FINISHED. Kruse will attend Rutgers, James A NEW CHIMNEY SWEEP. BOATS LEAVE RED BANK. Mrs. Mary E. VanBrunt of West VanNostrand will go to the Univer- WILL TEACH AT RED HIS WIFE AND HIS BUSINESS Long Branch bequeathed $G0O each ANNUAL TOUR OP MIDDLE- HIGH SCHOOL GRADUATING sity of Pennsylvania and Kileen THE WORK IS NOW DONE BY SEA BIRD AND ALBERTINA IK Walder will enter Simmons college BANK NEXT YEAR. PARTNER GET HIS ESTATE. to thrco grandsons, Clinton Davis, TOWN AGRICULTURE PUPIL3. EXERCISES LAST WEEK, ELECTRICITY. i NEW WATERS. ' ' Irving Davis and Wilbur Davis. The They Left Monday .Morning on a m Boston. S.T.nN.w Teacher. Will ba In,the Mn, Patterson Named »• Executrix sum of $100 was left to her son-in- ThI. Year's Claia Wat the Largatt Anson Hoyt will make a trip The Holland Ftirnace Company Gets They Will be UseTby Grtnam U*aj' <! Junior High School and Six In ih« r—George W. Ogllvie LMVM Estate law, William Davis, and the same . Bu» Trip to Varioui Placet and in tha Hi.torr of the School—Ex- around the world. He will sail as a Contracts to Sweep tha Chimneys Between New York and Midland River Street School—No Changes to Hii Wife—Wills of Other Rw sum was left to Catherine F. -

Winnipesaukee Marine Construction

THURSDAY, MAY 23, 2013 GILFORD, N.H. - FREE First annual Meadows tournament a success BY ERIN PLUMMER cer and Parks and Recre- fun tournament said par- [email protected] ation sports. ticipation was “right where It was a fun day on the The first phase is to lev- we wanted to be” and golf course benefiting play- el out the field, then it will around the target number ing fields, as the first annu- be sodded and an irrigation for the first tournament. al Meadows Golf Tourna- well will be installed. The Meadows Committee ment raised money for the first phase will be the cre- Chair Tim Drew said he first phase of the project. ation of two sodded multi- was happy with how the Golfers of all abilities use fields in addition to im- tournament went, saying gathered at Pheasant Ridge proving the current field as everyone had been so gen- Golf Club on Saturday well as the installation of erous for this great cause. morning for what is expect- an irrigation well. This The tournament was also ed to be the first annual golf phase is anticipated to cost “blessed with beautiful tournament benefiting ren- around $264,000. weather.” ovations and maintenance The tournament drew “We’re already looking of the Meadows athletic around 14 teams with over forward to next year’s tour- complex. 60 people out on the course. nament; even bigger and The Meadows property The four-person scram- better,”said Meadows Com- on Intervale Road was do- ble started around 8:30 a.m. -

A Methodological Guide for Educational Approaches to the European Folk Myths and Legends

Angela ACQUARO, Anthi APOSTOLIDOU, Lavinia ARAMĂ, Carmen-Mihaela BĂJENARU, Anetta BIENIARZ, Danuta BIENIEK, Joanna BRYDA-KŁECZEK, Mariele CARDONE, Sérgio CARLOS, Miguel CARRASQUEIRA, Daniela CERCHEZ, Neluța CHIRICA, Corina- Florentina CIUPALĂ, Florica CONSTANTIN, Mădălina CRAIOVEANU, Simona-Diana CRĂCIUN, Giovanni DAMBRUOSO, Angela DECAROLIS, Sylwia DOBRZAŃSKA, Anamaria DUMITRIU, Bernadetta DUŚ, Urszula DWORZAŃSKA, Alessandra FANIUOLO, Marcin FLORCZAK, Efstathia FRAGKOGIANNI, Ramune GEDMINIENE, Georgia GOGOU, Nazaré GRAÇA, Davide GROSSI, Agata GRUBA, Maria KAISARI, Maria KATRI, Aiste KAVANAUSKAITE LUKSE, Barbara KOCHAN, Jacek LASKA, Vania LIUZZI, Sylvia MASTELLA, Silvia MANEA, Lucia MARTINI, Paola MASCIULLI, Paula MELO, Ewa MICHAŁEK, Vittorio MIRABILE, Sandra MOTUZAITE-JURIENE, Daniela MUNTEANU, Albert MURJAS, Maria João NAIA, Asimina NEGULESCU, Helena OLIVEIRA, Marcin PAJA, Magdalena PĄCZEK, Adina PAVLOVSCHI, Małgorzata PĘKALA, Marioara POPA, Gitana PETRONAITIENE, Rosa PINHO, Monika POŹNIAK, Erminia RUGGIERO, Ewa SKWORZEC, Artur de STERNBERG STOJAŁOWSKI, Annalisa SUSCA, Monika SUROWIEC-KOZŁOWSKA, Magdalena SZELIGA, Marta ŚWIĘTOŃ, Elpiniki TASTANI, Mariusz TOMAKA, Lucian TURCU A METHODOLOGICAL GUIDE FOR EDUCATIONAL APPROACHES TO THE EUROPEAN FOLK MYTHS AND LEGENDS ISBN 978-973-0-34972-6 BRĂILA 2021 Angela ACQUARO, Anthi APOSTOLIDOU, Lavinia ARAMĂ, Carmen-Mihaela BĂJENARU, Anetta BIENIARZ, Danuta BIENIEK, Joanna BRYDA-KŁECZEK, Mariele CARDONE, Sérgio CARLOS, Miguel CARRASQUEIRA, Daniela CERCHEZ, Neluța CHIRICA, Corina- Florentina CIUPALĂ, -

Faneuil Hall Stands at the Eastern Edge of Dock Square (Intersection of Congress and North Streets) in Boston, Massachusetts

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATESDEPARTMEWOF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC Paneuil Hall AND/OR COMMON Paneuil Hall LOCATION STREET & NUMBER Dock Sauare fjlaneuil Hall —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Boston _ VICINITY OF Eighth STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Massachusetts 0? «» RifF-Fnllr A9C HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT X_PUBLIC XoCCUPlEO —AGRICULTURE X.MUSEUM X-BUILDING(S) —PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED ^—COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE _ ENTERTAINMENT _ RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS X.YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED —YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO _ MILITARY XpIHER DUbllC mAATLinir nAl T QOWNER OF PROPERTY NAME City of Boston, Office of the Mayor STREET & NUMBER New City Hall CITY. TOWN STATE Boston VICINITY OF Massachusetts HLOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEOS. ETC Suffolk County Registry of Deeds STREET & NUMBER Suffolk County Court House, Somerset Street CITY. TOWN STATE Boston Massachusetts Q REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Historic American Buildings Survey DATE 1935, 1937 X-FEDERAL _STATE —COUNTY _LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Library of Congress, Division of Prints and Photographs CITY. TOWN " " STATE Washington. D.C. DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE _EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED _UNALTERED X-ORIGINALSITE —GOOD _RUINS X-ALTERED —MOVED DATE- X_FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Faneuil Hall stands at the eastern edge of Dock Square (intersection of Congress and North Streets) in Boston, Massachusetts. -

JUSTICE LEAGUE UNLIMITED Jumpchain CYOA

May/19/2018 – v.2.4 SpyroAnon and KOTOR Anon JUSTICE LEAGUE UNLIMITED JumpChain CYOA Supervillains, criminals, aliens, monsters, robots, magicians, demons, gods, there are countless supernatural threats out there that can't be defeated by any single hero. So what happens when earth faces a threat greater than any single hero can handle? Simple, more than one hero comes to the planet's aid. Seven heroes in fact, and a few more later on. Welcome to the DC Universe, or rather one of the countless universes all bound together in the massive DC multiverse. This particular universe details the animated adventures of Superman, Batman, Wonder Woman, and several other major heroes as they try to defend the world while part of the newly formed Justice League! A team of superheroes dedicated to saving lives and protecting the world against supervillains and extra terrestrial threats. You'll arrive in this world a few hours before a powerful and merciless alien foe invades the earth and triggers a series of events that'll lead to the formation of the Justice League. You have 1000cp to spend of the choices below. Good luck. ._________________________________________________________________________________. Background Everyone has a past, even if that past is no past. Remember these are merely suggestions for a general theme or outline of your history. The exact details are up to you just note that you'll be relatively underwhelming until you gain some notoriety, barring any perks that screw with that anyway. All backgrounds are free. You may keep your current gender or change it at no cost and your starting age can be anywhere from 17 to 40. -

Staying Alive a Survival Manual for the Liberal Arts

STAYING ALIVE A SURVIVAL MANUAL FOR THE LIBERAL ARTS STAYING ALIVE A SURVIVAL MANUAL FOR THE LIBERAL ARTS L.O. Aranye Fradenburg edited by Eileen A. Joy with companion essays by Donna Beth Ellard, Ruth Evans, Eileen A. Joy, Julie Orlemanski, Daniel C. Remein & Michael D. Snediker punctum books ✶ brooklyn, ny STAYING ALIVE: A SURVIVAL MANUAL FOR THE LIBERAL ARTS © L.O. Aranye Fradenburg, 2013. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0 This work is Open Access, which means that you are free to copy, distribute, display, and perform the work as long as you clearly attribute the work to the authors, that you do not use this work for commercial gain in any form whatsoever, and that you in no way alter, transform, or build upon the work outside of its normal use in academ- ic scholarship without express permission of the author and the publisher of this volume. For any reuse or distri- bution, you must make clear to others the license terms of this work. First published in 2013 by punctum books Brooklyn, New York http://punctumbooks.com punctum books is an open-access independent publisher dedicated to radically creative modes of intellectual in- quiry and writing across a whimsical para-humanities as- semblage. punctum indicates thought that pierces and disturbs the wednesdayish, business-as-usual protocols of both the generic university studium and its individual cells or holding tanks. We offer spaces for the imp- orphans of your thought and pen, an ale-serving church for little vagabonds. We also take in strays. ISBN-13: 978-0615906508 ISBN-10: 0615906508 Cover Image: Nauerna — ladder (2010), by Ellen Kooi; with permission of the artist. -

The Viking Seax Knife

The Evolution of Materials in Arms and Armors: The Viking Seax Knife An Interactive Qualifying Project Report Submitted to the Faculty of the WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science By: Connor Morette Luke Proctor Matt Ryder Frederick Wight Date: March 6, 2015 Submitted to: Professor Diana A. Lados Mr. Tom H. Thomsen 1 Table of Contents List of Figures ............................................................................................................................ 4 List of Tables ............................................................................................................................. 6 Authorship .................................................................................................................................. 7 Matt Ryder: ............................................................................................................................. 7 Connor Morette: ..................................................................................................................... 7 Luke Proctor: .......................................................................................................................... 7 Frederick Wight: ..................................................................................................................... 7 1. Abstract .................................................................................................................................. 8 2. Introduction ...........................................................................................................................