Jack Waddell's Heritage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Constituency: Newry and Armagh

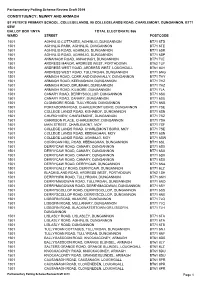

Parliamentary Polling Scheme Review Draft 2019 CONSTITUENCY: NEWRY AND ARMAGH ST PETER'S PRIMARY SCHOOL, COLLEGELANDS, 90 COLLEGELANDS ROAD, CHARLEMONT, DUNGANNON, BT71 6SW BALLOT BOX 1/NYA TOTAL ELECTORATE 966 WARD STREET POSTCODE 1501 AGHINLIG COTTAGES, AGHINLIG, DUNGANNON BT71 6TD 1501 AGHINLIG PARK, AGHINLIG, DUNGANNON BT71 6TE 1501 AGHINLIG ROAD, AGHINLIG, DUNGANNON BT71 6SR 1501 AGHINLIG ROAD, AGHINLIG, DUNGANNON BT71 6SP 1501 ANNAHAGH ROAD, ANNAHAGH, DUNGANNON BT71 7JE 1501 ARDRESS MANOR, ARDRESS WEST, PORTADOWN BT62 1UF 1501 ARDRESS WEST ROAD, ARDRESS WEST, LOUGHGALL BT61 8LH 1501 ARDRESS WEST ROAD, TULLYROAN, DUNGANNON BT71 6NG 1501 ARMAGH ROAD, CORR AND DUNAVALLY, DUNGANNON BT71 7HY 1501 ARMAGH ROAD, KEENAGHAN, DUNGANNON BT71 7HZ 1501 ARMAGH ROAD, DRUMARN, DUNGANNON BT71 7HZ 1501 ARMAGH ROAD, KILMORE, DUNGANNON BT71 7JA 1501 CANARY ROAD, DERRYSCOLLOP, DUNGANNON BT71 6SU 1501 CANARY ROAD, CANARY, DUNGANNON BT71 6SU 1501 CLONMORE ROAD, TULLYROAN, DUNGANNON BT71 6NB 1501 PORTADOWN ROAD, CHARLEMONT BORO, DUNGANNON BT71 7SE 1501 COLLEGE LANDS ROAD, KISHABOY, DUNGANNON BT71 6SN 1501 CHURCHVIEW, CHARLEMONT, DUNGANNON BT71 7SZ 1501 GARRISON PLACE, CHARLEMONT, DUNGANNON BT71 7SA 1501 MAIN STREET, CHARLEMONT, MOY BT71 7SF 1501 COLLEGE LANDS ROAD, CHARLEMONT BORO, MOY BT71 7SE 1501 COLLEGE LANDS ROAD, KEENAGHAN, MOY BT71 6SN 1501 COLLEGE LANDS ROAD, AGHINLIG, MOY BT71 6SW 1501 CORRIGAN HILL ROAD, KEENAGHAN, DUNGANNON BT71 6SL 1501 DERRYCAW ROAD, CANARY, DUNGANNON BT71 6SX 1501 DERRYCAW ROAD, CANARY, DUNGANNON BT71 6SX 1501 DERRYCAW ROAD, -

Regional Addresses

Northern Ireland Flock Address Tel. No. Mr Jonathan Aiken ZXJ 82 Corbally Road Carnew Dromore Co Down, N Ireland BT25 2EX 07703 436008 07759 334562 Messrs J & D Anderson XSR 14 Ballyclough Road Bushmills N Ireland BT57 8TU 07920 861551 - David Mr Glenn Baird VAB 37 Aghavilly Road Amagh Co. Armagh BT60 3JN 07745 643968 Mr Gareth Beacom VCT 89 Castle Manor Kesh Co. Fermanagh N. Ireland BT93 1RZ 07754 053835 Mr Derek Bell YTX 58 Fegarron Road Cookstown Co Tyrone Northern Ireland BT80 9QS 07514 272410 Mr James Bell VDY 25 Lisnalinchy Road Ballyclare Co. Antrim BT39 9PA 07738 474516 Mr Bryan Berry WZ Berry Farms 41 Tullyraine Road Banbridge Co Down Northern Ireland BT32 4PR 02840 662767 Mr Benjamin Bingham WLY 36 Tullycorker Road Augher Co Tyrone N. Ireland BT77 0DJ 07871 509405 Messrs G & J Booth PQ 82 Ballymaguire Road Stewartstown, Co Tyrone N.Ireland, BT71 5NQ 07919 940281 John Brown & Sons YNT Beechlodge 12 Clay Road Banbridge Co Down Northern Ireland BT32 5JX 07933 980833 Messrs Alister & Colin Browne XWA 120 Seacon Road Ballymoney Co Antrim N Ireland BT53 6PZ 07710 320888 Mr James Broyan VAT 116 Ballintempo Road Cornacully Belcoo Co. Farmanagh BT39 5BF 07955 204011 Robin & Mark Cairns VHD 11 Tullymore Road Poyntzpass Newry Co. Down BT35 6QP 07783 676268 07452 886940 - Jim Mrs D Christie & Mr J Bell ZHV 38 Ballynichol Road Comber Newtownards N. Ireland BT23 5NW 07532 660560 - Trevor Mr N Clarke VHK 148 Snowhill Road Maguiresbridge BT94 4SJ 07895 030710 - Richard Mr Sidney Corbett ZWV 50 Drumsallagh Road Banbridge Co Down N Ireland BT32 3NS 07747 836683 Mr John Cousins WMP 147 Ballynoe Road Downpatrick Co Down Northern Ireland BT30 8AR 07849 576196 Mr Wesley Cousins XRK 76 Botera Upper Road Omagh Co Tyrone N Ireland BT78 5LH 07718 301061 Mrs Linda & Mr Brian Cowan VGD 17 Owenskerry Lane Fivemiletown Co. -

Aptart 1982-84 - Exhibition Histories Pdf, Epub, Ebook

ANTI-SHOWS: VOLUME 8 : APTART 1982-84 - EXHIBITION HISTORIES PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Alexandra Danilova | 256 pages | 26 Sep 2017 | Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther Konig,Germany | 9783960980230 | English | Germany Anti-Shows: Volume 8 : Aptart 1982-84 - Exhibition Histories PDF Book Yale University Press, New York. M ag h Ar m century resulting in Hullavill. In Stock. A Life in Art. In respect to monetary loss, the flood was the most disastrous in the history of the basin. Learning by teaching evidence-based strategies to enhance learning in the classroom David Duran and Keith Topping. Robinson, Coragh. During the report year, December 1, , to November 30, , precipitation and runoff varied from below average to above average in the Delaware River Basin. We used VT events with 16, P- and 16, S-wave arrival time phases recorded by 6 stations for the tomographic inversion. Bookworks, London. Government Printing Office, , Occasional Papers, Form Content, London. Toop, David Sinister resonance: the mediumship of the listener. TEH, David ed. Hamilton son ot the Rev. Ediciones UDP, Santiago. These sections contain articles…. The study area encompassed square miles and was bounded to the north by the Atlantic Ocean, to the south by the southern extension of the limestone units, to the west by the Rio Grande de Arecibo, and to the east by the Rio Grande de Manati pls. I us eu m -6Thomas Dawson, Esq. Begum, Lipi and Dasgupta, Rohit K. Bl:ethen Peter Luster Thos. Aesthetic Practice after Autonomy. Granary Books. Royal Academy. Some eu M us eu m us nt C y the General Synod or Ulster a plan tor the education or ag h M students designed for the ministry, a treatise printed in ou rm ag ou four years after his arrival in the city he Sllbnitted to us eu m y ou nt M Later, in , C ou nt y instrumental in obtaining an augmentation or the Ar m he was ag h an address from the Presbytery of Armagh. -

THE BELFAST GAZETTE, SEPTEMBER 30, 1938. Gagh, Corporation, Drumadd, Drumarg, TIRANNY BARONY

334 THE BELFAST GAZETTE, SEPTEMBER 30, 1938. gagh, Corporation, Drumadd, Drumarg, TIRANNY BARONY. or Downs, Drumcote, Legarhil], Long- Eglish Parish (part of). stone, Lurgyvallen, Parkmore, or Demesne, .Tullyargle, Tullyelmer, Ballybrocky, Garvaghy, Lisbane, Lis- Tullylost, Tullymore, Tullvworgle, down, Tullyneagh, Tullysaran. Tyross, or Legagilly, Umgola. Clonfeacle Parish (part of). Ballytroddan, Creaghan. PORTADOWN PETTY SESSIONS Derrynoose Parish (part of). DISTRICT. Lisdrumbrughas, Maghery Kilcrany. Eglish Parish. (As constituted by an Order made on 5th August, 1938, under Section 10 of the Aughrafin, Ballaghy, Ballybrolly, Bally- Summary Jurisdiction and Criminal doo, Ballymartrim Etra, B'allymartrim Justice Act (N.L), 1935). Otra, Ballyscandal, Bracknagh, Clogh- fin, Creeveroe, Cullentragh, Drumbee, ONEILLAND, EAST, BARONY. Knockagraffy, Lisadian, Navan, Tam- laght, Terraskane, Tirgarriff, Tonnagh, Seagoe Parish (part of). Tray, Tullynichol. Ballydonaghy, Ballygargan, Ballyhan- Grange Parish (part of). non, Ballymacrandal, Ballynaghy, Bo- combra, Breagh, Carrick, Derryvore, Aghanore, Allistragh, Aughnacloy, Drumlisnagrilly, Drumnacanvy, Eden- Ballymackillmurry, Cabragh, Cargana- derry, Hacknahay, Kernan, Killyco- muck, Carrickaloughran, Carricktrod- main, Knock, Knocknamuckly, Levagh- dan, Drumcarn, Drumsill, Grangemore, ery, Lisnisky, Lylo, Seagoe, Lower; Killylyn, Lisdonwilly, Moneycree, Seagoe, Upper; Tarsan. Mullynure, Teeraw, Tullyard, TuIIy- garran. ONEILLAND, WEST, BARONY. Lisnadill Parish. Drumcree Parish (part of). Aghavilly, -

1951 Census Armagh County Report

GOVERNMENT OF NORTHERN IRELAND CENSUS OF POPULATION OF NORTHERN IRELAND 1951 County of Armagh Printed & presented pursuant to 14 & 15 Geo. 6, Ch. 6 BELFAST : HER MAJESTY'S STATIONERY OFFICE 1954 PRICE 7s M NET GOVERNMENT OF NORTHERN IRELAND CENSUS OF POPULATION OF NORTHERN ffiELAND 1951 County of Armagh Printed & presented pursuant to 14 & 15 Geo. 6, Ch. 6 BELFAST ; HER MAJESTY'S STATIONERY OFFICE 1954 PREFACE Three censuses of population have been taken since the Governinent of Northern Ireland was established. The first enumeration took place in 1926 and incorporated questions relating to occupation and industry, orphanhood and infirmities. The second enumeration made in 1937 was of m^ore limited scope and was intended to bridge the gap between the census of 1926 and the census which it was proposed to take in 1941, but which had to be abandoned owing to the outbreak of war. The census taken as at mid night of 8th-9th April, 1951, forms the basis of this report and like that in 1926 questions were asked as to the occupations and industries of the population. The length of time required to process the data collected at an enumeration before it can be presented in the ultimate reports is necessarily considerable. In order to meet immediate requirements, however, two Preliminary Reports on the 1951 census were published. The first of these gave the population figures by administrative areas and towns and villages, and by Counties and County Boroughs according to religious profession. The Second Report, which was restricted to Counties and County Boroughs, gave the population by age groups. -

002114 After the Loss of a Baby.Pdf

Maternal and Child Program After the Loss of a Baby What’s Inside: Dear Family, The staff at HRH wish to extend our condolences to you Grieving the Loss of your Baby .......................2 and your family on the loss of your baby. Collecting Keepsakes .........................................2 At this extremely difficult time, you may find it hard to cope, both practically and emotionally. You will probably The Role of Spiritual Care .................................3 have many questions. Arranging your Baby’s Care .............................3 We would like to share information that other parents Telling Your Child(ren) about the Baby ........5 found helpful. This booklet contains information that can help you understand what happens next and deal Grandparents Grieve Too ..................................6 openly with the physical and emotional changes you will Caring for Yourself ...............................................6 experience. We also encourage you to speak to us with any other questions you may have at any time. Appendix A. Resources for Coping Please feel free to take this booklet home, along with any with Grief ................................................................8 keepsakes of your baby. You may not be ready to read the Appendix B. Funeral Homes ...........................9 booklet now. However, as you start to heal, you may find that your feelings change in time. Appendix C. Cemeteries ................................13 Notes ......................................................................14 If you have questions or need help, please talk with your health care providers: Doctor: Tel: ____________________________________________ Social Worker: Tel: ____________________________________________ Chaplain/ Tel: Spiritual Care Provider: ____________________________________________ Child Life Specialist: Tel: ____________________________________________ Form # 002114 © 2015_06 REV 2015_11 www.hrh.ca Grieving the Loss of your Baby What can I do? Grief is the normal response that you go through • See, hold or touch your baby. -

UHF4/94/15 Whitlock Report Tirnascobe Often Spelt Ternascobe

UHF4/94/15 Whitlock Report Tirnascobe often spelt Ternascobe in the local records is a townland of 538 acres. Both Tirnascobe and Altaturk townlands are now in the parish of Kildarton. Before 1836 at which date the parish boundaries were re-organised, Tirnasobe was in the parish of Armagh and Allaturk was in the parish of Loughgall. Both townlands belonged to the Estate of the Rt Hon. the Earl of Charlemont. Maps accompany this report which may help the client, the parishes of Kildarton, Armagh and Loughgall are found in the north• west section of County Armagh. The client's suppositions concerning her family proved to be true, confirmed, by a baptism found in the Armagh Church of Ireland registers. r. If" 15 March 1812 Gregory son of John and Susannah Whitelock. No place of residence ~~.; '1:> birthis named.of theirThefirstregisterschild. Wewerenotedsearchedany recordsuntil 1818,for thecoveringsurnamea 20Gregory.year periodAccordingfrom theto the client the names Gregory and Susanna appear in the family at a later date. The families place of residence is given as Altaturk, previously in the parish of Loughgall. The Tithe Applotment Book 1830 for the parish of Loughgall lists a John Whiteford \_~\~~ Legavillyin the townlandleasing 20of Mullinasilleyacres, 3 roods,having10 perches.11 acres, 2 roods and a Morris Whitelock in Several miscellaneous estate records for the area were looked at two and references ~ \?l:- to Whitlocks found. Nicholas Whitlock of Loughgall is a churchwarden of Armagh Cathedral in 1798 where John and Susanna Whitlocks children were baptised. The other reference is found in a rental dated 1721-24 for the Manor of Castle Dillon property of the Hon. -

EONI-REP-223 - Streets - Streets Allocated to a Polling Station by Area Local Council Elections: 02/05/2019

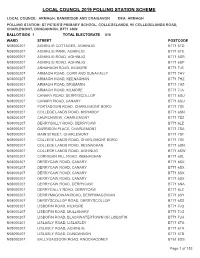

EONI-REP-223 - Streets - Streets allocated to a Polling Station by Area Local Council Elections: 02/05/2019 LOCAL COUNCIL: ARMAGH, BANBRIDGE AND CRAIGAVON DEA: ARMAGH ST PETER'S PRIMARY SCHOOL, COLLEGELANDS, 90 COLLEGELANDS ROAD, CHARLEMONT, DUNGANNON, BT71 6SW BALLOT BOX 1/AR TOTAL ELECTORATE 810 WARD STREET POSTCODE N08000207 AGHINLIG COTTAGES, AGHINLIG, DUNGANNON BT71 6TD N08000207 AGHINLIG PARK, AGHINLIG, DUNGANNON BT71 6TE N08000207 AGHINLIG ROAD, AGHINLIG, DUNGANNON BT71 6SR N08000207 AGHINLIG ROAD, AGHINLIG, DUNGANNON BT71 6SP N08000207 ANNAHAGH ROAD, KILMORE, DUNGANNON BT71 7JE N08000207 ARMAGH ROAD, CORR AND DUNAVALLY, DUNGANNON BT71 7HY N08000207 ARMAGH ROAD, KEENAGHAN, DUNGANNON BT71 7HZ N08000207 ARMAGH ROAD, DRUMARN, DUNGANNON BT71 7HZ N08000207 ARMAGH ROAD, KILMORE, DUNGANNON BT71 7JA N08000207 CANARY ROAD, DERRYSCOLLOP, DUNGANNON BT71 6SU N08000207 CANARY ROAD, CANARY, DUNGANNON BT71 6SU N08000207 PORTADOWN ROAD, CHARLEMONT BORO, DUNGANNON BT71 7SE N08000207 COLLEGE LANDS ROAD, KISHABOY, DUNGANNON BT71 6SN N08000207 CHURCHVIEW, CHARLEMONT, DUNGANNON BT71 7SZ N08000207 DERRYGALLY ROAD, DERRYCAW, DUNGANNON BT71 6LZ N08000207 GARRISON PLACE, CHARLEMONT, DUNGANNON BT71 7SA N08000207 MAIN STREET, CHARLEMONT, MOY BT71 7SF N08000207 COLLEGE LANDS ROAD, CHARLEMONT BORO, MOY BT71 7SE N08000207 COLLEGE LANDS ROAD, KEENAGHAN, MOY BT71 6SN N08000207 COLLEGE LANDS ROAD, AGHINLIG, MOY BT71 6SW N08000207 CORRIGAN HILL ROAD, KEENAGHAN, DUNGANNON BT71 6SL N08000207 DERRYCAW ROAD, CANARY, DUNGANNON BT71 6SX N08000207 DERRYCAW ROAD, CANARY, -

The Humber River: the 10-Year Monitoring Report for the Canadian Heritage Rivers System October 2009 Lower Humber Valley, Toronto, TRCA, 2008

THE HUMBER RIVER: THE 10-YEAR MONITORING REPORT FOR THE CANADIAN HERITAGE RIVERS SYSTEM October 2009 Lower Humber Valley, Toronto, TRCA, 2008 THE HUMBER CHALLENGE Our challenge is to protect and enhance the Humber River watershed as a vital and healthy ecosystem where we live, work and play in harmony with the natural environment. GUIDING PRINCIPLES To achieve a healthy watershed, we should: • Increase awareness of the watershed’s resources • Protect the Humber River as a continuing source of clean water • Celebrate, regenerate, and preserve our natural, historical and cultural heritage • Increase community stewardship and take individual responsibility for the health of the Humber River • Establish linkages and promote partnerships among communities • Build a strong watershed economy based on ecological health, and • Promote the watershed as a destination of choice for recreation and tourism The Humber River: The 10-Year Monitoring Report for the Canadian Heritage Rivers System i FRAGMENT: THE VALLEY Like a sweet wine flowing from the glass, the Humber of my boyhood years! First the stretch of the river valley as I knew it best, running south from Dundas Street to my beloved stone marvel of the Old Mill Bridge, a scant mile to the south, not forgetting to count a quarter-mile jog to the east halfway down to heighten the wonderment. What force of ten million years’ cunning erosion, the relentless path of an awkward giant carving out for himself great steps one by one as he strides on and on, thirsty now for a great cold draught of Lake Ontario water! What sheer-climbing cliffs with the history of planet Earth carved in each layer of shale reaching up a hundred feet from the shining valley floor, the littered rocks of the river …. -

Local Council 2019 Polling Station Scheme

LOCAL COUNCIL 2019 POLLING STATION SCHEME LOCAL COUNCIL: ARMAGH, BANBRIDGE AND CRAIGAVON DEA: ARMAGH POLLING STATION: ST PETER'S PRIMARY SCHOOL, COLLEGELANDS, 90 COLLEGELANDS ROAD, CHARLEMONT, DUNGANNON, BT71 6SW BALLOT BOX 1 TOTAL ELECTORATE 816 WARD STREET POSTCODE N08000207AGHINLIG COTTAGES, AGHINLIG BT71 6TD N08000207AGHINLIG PARK, AGHINLIG BT71 6TE N08000207AGHINLIG ROAD, AGHINLIG BT71 6SR N08000207AGHINLIG ROAD, AGHINLIG BT71 6SP N08000207ANNAHAGH ROAD, KILMORE BT71 7JE N08000207ARMAGH ROAD, CORR AND DUNAVALLY BT71 7HY N08000207ARMAGH ROAD, KEENAGHAN BT71 7HZ N08000207ARMAGH ROAD, DRUMARN BT71 7HZ N08000207ARMAGH ROAD, KILMORE BT71 7JA N08000207CANARY ROAD, DERRYSCOLLOP BT71 6SU N08000207CANARY ROAD, CANARY BT71 6SU N08000207PORTADOWN ROAD, CHARLEMONT BORO BT71 7SE N08000207COLLEGE LANDS ROAD, KISHABOY BT71 6SN N08000207CHURCHVIEW, CHARLEMONT BT71 7SZ N08000207DERRYGALLY ROAD, DERRYCAW BT71 6LZ N08000207GARRISON PLACE, CHARLEMONT BT71 7SA N08000207MAIN STREET, CHARLEMONT BT71 7SF N08000207COLLEGE LANDS ROAD, CHARLEMONT BORO BT71 7SE N08000207COLLEGE LANDS ROAD, KEENAGHAN BT71 6SN N08000207COLLEGE LANDS ROAD, AGHINLIG BT71 6SW N08000207CORRIGAN HILL ROAD, KEENAGHAN BT71 6SL N08000207DERRYCAW ROAD, CANARY BT71 6SX N08000207DERRYCAW ROAD, CANARY BT71 6SX N08000207DERRYCAW ROAD, CANARY BT71 6SX N08000207DERRYCAW ROAD, CANARY BT71 6SX N08000207DERRYCAW ROAD, DERRYCAW BT71 6NA N08000207DERRYGALLY ROAD, DERRYCAW BT71 6LZ N08000207DERRYMAGOWAN ROAD, DERRYMAGOWAN BT71 6SY N08000207DERRYSCOLLOP ROAD, DERRYSCOLLOP BT71 6SS N08000207LISBOFIN -

Polling Station Scheme Review - Local Council

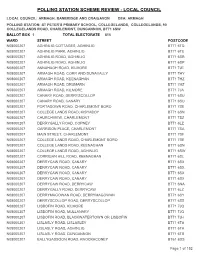

POLLING STATION SCHEME REVIEW - LOCAL COUNCIL LOCAL COUNCIL: ARMAGH, BANBRIDGE AND CRAIGAVON DEA: ARMAGH POLLING STATION: ST PETER'S PRIMARY SCHOOL, COLLEGELANDS, COLLEGELANDS, 90 COLLEGELANDS ROAD, CHARLEMONT, DUNGANNON, BT71 6SW BALLOT BOX 1 TOTAL ELECTORATE 815 WARD STREET POSTCODE N08000207AGHINLIG COTTAGES, AGHINLIG BT71 6TD N08000207AGHINLIG PARK, AGHINLIG BT71 6TE N08000207AGHINLIG ROAD, AGHINLIG BT71 6SR N08000207AGHINLIG ROAD, AGHINLIG BT71 6SP N08000207ANNAHAGH ROAD, KILMORE BT71 7JE N08000207ARMAGH ROAD, CORR AND DUNAVALLY BT71 7HY N08000207ARMAGH ROAD, KEENAGHAN BT71 7HZ N08000207ARMAGH ROAD, DRUMARN BT71 7HZ N08000207ARMAGH ROAD, KILMORE BT71 7JA N08000207CANARY ROAD, DERRYSCOLLOP BT71 6SU N08000207CANARY ROAD, CANARY BT71 6SU N08000207PORTADOWN ROAD, CHARLEMONT BORO BT71 7SE N08000207COLLEGE LANDS ROAD, KISHABOY BT71 6SN N08000207CHURCHVIEW, CHARLEMONT BT71 7SZ N08000207DERRYGALLY ROAD, COPNEY BT71 6LZ N08000207GARRISON PLACE, CHARLEMONT BT71 7SA N08000207MAIN STREET, CHARLEMONT BT71 7SF N08000207COLLEGE LANDS ROAD, CHARLEMONT BORO BT71 7SE N08000207COLLEGE LANDS ROAD, KEENAGHAN BT71 6SN N08000207COLLEGE LANDS ROAD, AGHINLIG BT71 6SW N08000207CORRIGAN HILL ROAD, KEENAGHAN BT71 6SL N08000207DERRYCAW ROAD, CANARY BT71 6SX N08000207DERRYCAW ROAD, CANARY BT71 6SX N08000207DERRYCAW ROAD, CANARY BT71 6SX N08000207DERRYCAW ROAD, CANARY BT71 6SX N08000207DERRYCAW ROAD, DERRYCAW BT71 6NA N08000207DERRYGALLY ROAD, DERRYCAW BT71 6LZ N08000207DERRYMAGOWAN ROAD, DERRYMAGOWAN BT71 6SY N08000207DERRYSCOLLOP ROAD, DERRYSCOLLOP BT71 6SS -

Irish Local Names Explained

iiiiiiiiiiiSi^SSSSiSSSSiSS^-^SSsS^^^ QiaM.^-hl IRISH <^ LOCAL NAMES EXPLAINED. P. W. JOYCE, LL.D., M.R.I.A. Cpiallam cimceall na po&la. iiEW EDITION} DUBLIN: M. H. GILL & SON, 50, UPPEE SACKYILLE STREET. LONDON : WHITTAKER & CO. ; SIMPKIN, MARSHALL & CO. EDINBURGH : JOHN MENZIES & CO. 31. n. OTLL AKD SON, PEINTKES, DvBLI.f^ • o . PREFACE. 1 HAVE condensed into this little volume a consi- derable part of the local etymologies contained in " The Origin and History of Irish Names of Places." 1 have generally selected those names that are best known through the country, and I have thought it better to arrange them in alpha- betical order. The book has been written in the hope that it may prove useful, and perhaps not uninteresting, to those who are anxious for information on the subject, but who have not the opportunity of perusing the larger volume. Soon after the appearance of "The Origin and History of Irish Names of Places," I received from correspondents in various parts of Ireland communications more or less valuable on the topo- graphy, legends, or antiquities of their respective localities. I take this opportunity of soliciting further information from those who are able to give it, and who are anxious to assist in the advancement of Irish literature. IRISH LOCAL NAMES EXPLATKED. THE PROCESS OF ANGLICISING. 1. Systematic Changes. Irish prommciation preserved. —In anglicising Irish names, the leading general rule is, that the present forms are derived from the ancient Irish, as they were spoken, not as they were written. Those who first committed them to writing, aimed at preserving the original pronunciation, by representing it as nearly as they were able in English letters.