The Shakespeare Code Reveals the Story of Codes Concealed in the Works of Shakespeare and Other Writers of His Time

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1925-1926 Baconiana No 68-71.Pdf

m ■ lilSl « / , . t ! i■ i J l Vol. XVIII. Third Series. Comprising March & Dec. 1925, April & Dec., 1926. BACONIAN A -A ^Periodical ^ttagazine 1 5 [ T ) ) l l 7 LONDON: > GAY & HANCOCK, Limited, \ 12 AND 13, HENRIETTA ST., STRAND, W .C. I927 ‘ ’ Therefore we shall make our judgment upon the things themselves as they give light one to another and, as we can, dig Truth out of the mine.”—Francis Bacon r '■ CONTENTS. MARCH, 1925. page. The 364th Anniversary Dinner 1 Who was Shakespeare ? 10 The Eternal Controversy about Shakespeare 15 Shakespeare’s ‘ 'Augmentations’'. 18 An Historical Sketch of Canonbury Tower. 26 Shakespeare—Bacon’s Happy Youthful Life 37 ' 'Notions are the Soul of Words’' 43 Cambridge University and Shakespeare 52 Reports of Meetings 55 Sir Thomas More Again .. 60 George Gascoigne 04 Book Notes, Notes, etc. 67 DECEMBER, 1925. Biographers of Bacon 73 Bacon the Expert on Religious Foundations S3 ‘ ‘Composita Solvantur’ ’ . 90 Notes on Anthony Bacon’s Passports of 1586 93 The Shadow of Bacon’s Mind 105 Who Wrote the “Shakespeare” play, Henry VIII ? 117 Shakespeare and the Inns of Court 127 Book Notices 133 Correspondence .. 134 Notes and Notices 140 APRIL, 1926. Introduction to the Tercentenary Number r45 Introduction by Sir John A. Cockburn M7 The “Manes Verulamiani’' (in Latin and English), with Notes 157 Bacon and Seats of Learning 203 Francis Bacon and Gray’s Inn 212 Bacon and the Drama 217 Bacon as a Poet 227 Bacon on Himself 230 Bacon’s Friends and Critics 237 Bacon in the Shadow 259 Bacon as a Cryptographer 267 Appendix 269 Pallas Athene 272 Book Notices, Notes, etc. -

Henry Neville and the Shakespeare Code Free

FREE HENRY NEVILLE AND THE SHAKESPEARE CODE PDF Brenda James | 380 pages | 30 Apr 2008 | Music for Strings | 9781905424054 | English | Bognor Regis, United Kingdom [PDF] secrets of the sonnets shakespeare s code eBook Uh-oh, it looks like your Internet Explorer Henry Neville and the Shakespeare Code out of date. For a better shopping experience, please upgrade now. Javascript is not enabled in your browser. Enabling JavaScript in your browser will allow you to experience all the features of our site. Learn how to enable JavaScript on your Henry Neville and the Shakespeare Code. Home 1 Books 2. Henry Neville and the Shakespeare Code to Wishlist. Sign in to Purchase Instantly. Members save with free shipping everyday! See details. Overview Sir Henry Neville - the true author of Shakespeare's works - the discovery that Henry Neville and the Shakespeare Code a sensation in the literary world. Shakespeare historian, Brenda James, always felt that the dedication to the sonnets may have contained a code - but for what purpose? How could it be cracked? When her research led to a little-known code breaking technique, she did not suspect that this would reveal a year old secret - the name of the real author. This book outlines James' investigation and previously unpublished material: code breaking, the discovery of forgotten documents and years of detailed research and analysis. Her journey unravels the mysteries behind the sonnets and explains some of the most obscure references in the plays. Find out why Sir Henry's authorship remained undiscovered for almost four centuries. Product Details. Related Searches. This coloring book is for the beginner and experienced colorist of any age and includes 25 designs Henry Neville and the Shakespeare Code from simple to complex. -

1935 Baconiana No 83

VoL XXII. No. 83 (Third Series.) Price 2/6 net BACONIANA OCTOBER, 1935. CONTENTS. PAGE. The Bacon Society's Annual Dinner - - - - 49 The Bacon-Marlowe Problem. By Bertram G. Theobald, B.A. - - - - - ' - 58 The Gallup Decipher. By C.L'Estrange Ewen - 60 Joseph Addison and Francis Bacon. By Alicia A. Leith - - - - - - - - - - - 80 Typographical Mistakes in Shakespeare. By Howard Bridgewater - - - - - - - - 87 Was " William Shake-speare" the Creator of the Rituals of Freemasonry? By Wor. Bro. Alfred Dodd - : - - - - - - - - - - 95 Francis Bacon—Patriot. By D. Gomes da Silva - - 102 Mrs. Elizabeth Wells Gallup (In Memoriam). By HenrySeymour - - - - - 7 106 A Calendar of the Inner Temple Records - - 110 I Bacon Society Lectures and Discussions - - Ill Jonson Talks - 112 Book Notice 115 Correspondence 116 Notes and Notices 117 LONDON: THE BACON SOCIETY INCORPORATED 47, GORDON SQUARE, W.C.l. The Bacon Society (incorporated). 47 GORDON SQUARE, LONDON, W.C.i The objects of the Society are expressed in the Memorandum of Association to be:— 1. To encourage the study of the works of Francis Bacon as philosopher, lawyer, statesman and poet; also his character, genius and life; his influence on his own and succeeding times and the tendencies and results of his writings. 2. To encourage the general study of the evidence in favour of his authorship of the plays commonly ascribed to Shakspcre, and to investigate his connection with other works of the period. Annual Subscription. For Members who receive, without further payment, two copies of Baconiana (the Society's Magazine) and are entitled to vote at the Annual General Meeting, one guinea. For Associates, who receive one copy, half-a-guinea. -

Decoding Shakespeare: the Bard As

DECODING SHAKESPEARE: THE BARD AS POET OR POLITICIAN? by R.V. Young In recent years the most notable trend in Shakespeare studies has been the investigation of the playwright’s Catholic religious orientation and the exposition of its significance for the interpretation of his plays and poems. This trend may have reached its culmination with the publication in 2004 of Richard Wilson’s Secret Shakespeare: Studies in theatre, religion and resistance and Clare Asquith’s Shadowplay: The Hidden Beliefs and Coded Politics of William Shakespeare in the following year. Both of these books assert unequivocally not only that Shakespeare was reared a Catholic and remained so throughout his life, but also that his Catholic Recusancy shaped his career as a poet and dramatist to such an extent that his works may be read as an encoded account of the tribulations and dissident activities of the English Recusant community under Queen Elizabeth and during early years of King James’s reign. In Asquith’s words, the aim is to overturn Shakespeare’s image as “a writer so outstanding that the politics of his time are irrelevant, even distracting.” “Instead of diminishing Shakespeare’s work,” she maintains, “awareness of the shadowed language deepens it, adding a cutting edge of contemporary reference to the famously universal plays and giving them an often acutely poignant hidden context” (xiv-xv). Writing in a New Historicist mode, Richard Wilson is even more explicit about dismantling the longstanding image of Shakespeare as the Bard of universal human significance: Like the film [Shakespeare in Love], the construction of a 2 Shakespeare in love with Protestant empire serves the ideological function of annexing the plays to the dominant Anglo-Saxon discourses of populism and individualism, and so to globalisation and American hegemony. -

Mask and Persona: Creating the Bard for Bardcom

Persona Studies 2019, vol. 5, no. 2 MASK AND PERSONA: CREATING THE BARD FOR BARDCOM PETER HOLLAND ABSTRACT This article explores a number of perspectives on the creation of very different Shakespeares as personas by first examining the celebration of the 400th anniversary of his death in Stratford-upon-Avon in April 2016 and Shake, Mr Shakespeare, a remarkable Roy Mack 1936 Warner Brothers short. From there it moves on to consider the brief appearance of Shakespeare in the time-travel comedy Blackadder: Back and Forth, in ‘The Shakespeare Code’ episode of Doctor Who and in the off-Broadway musical Something Rotten!, before examining the work of Ben Elton in his screenplay for All Is True and in the seemingly unlikely success of Upstart Crow, the BBC sitcom with Shakespeare as the lead character, which has so far completed three six-episode series and three Christmas specials. The article is concerned with the multiple masks of the sequence of personas that create these Shakespeares, from Shakespeare as perhaps the epitome of the celebrity author to Shakespeare as a sitcom Dad. KEY WORDS Shakespeare, Mask, Celebrity, Comedy, Sitcom, Afterlife WHERE ISS SHAKESPEARE? In Act 2 of Emlyn Williams’ The Corn is Green (1938), a semi-autobiographical narrative of how education saved a bright Welsh boy from the mines and sent him to Oxford University, the end of a class in Miss Moffat’s new school leaves behind on stage Old Tom, “an elderly, distinguished- looking, grey-bearded peasant” (Williams 1995, p. 34), and Miss Ronberry, now one of Miss Moffat’s teachers. -

1925-1926 Baconiana No 68-71

■ j- I Vol. XVIII. Third Series. Comprising March & Dec. 1925, April & Dec., 1926. BACONIANA 'A ^periodical ^Magazine 5 I ) ) I LONDON: 1 GAY & HANCOCK, Limited, I 12 AND 13, HENRIETTA ST., STRAND, W.C. I927 ► “ Therefore we shall make our judgment upon the things themselves as they give light one to another and, as we can, dig Truth out of the mine ' ’—Francis Bacon <%■ 1 % * - ■ ■ CONTENTS. MARCH, 1925. PAGE. The 364th Anniversary Dinner I Who was Shakespeare ? .. IO The Eternal Controversy about Shakespeare 15 Shakespeare’s ' 'Augmentations’'. 18 An Historical Sketch of Canonbury Tower. 26 Shakespeare—Bacon’s Happy Youthful Life 37 ' ‘Notions are the Soul of Words’ ’ 43 Cambridge University and Shakespeare 52 Reports of Meetings 55 Sir Thomas More Again .. 60 George Gascoigne 04 Book Notes, Notes, etc. .. 67 DECEMBER, 1925. Biographers of Bacon 73 Bacon the Expert on Religious Foundations 83 ' 'Composita Solvantur’ ’ .. 90 Notes on Anthony Bacon’s Passports of 1586 93 The Shadow of Bacon’s Mind 105 Who Wrote the “Shakespeare” play, Henry VIII? 117 Shakespeare and the Inns of Court 127 Book Notices 133 Correspondence .. 134 Notes and Notices 140 APRIL, 1926. Introduction to the Tercentenary Number .. 145 Introduction by Sir John A. Cockburn 147 The “Manes Verulamiani” (in Latin and English), with Notes 157 Bacon and Seats of Learning 203 Francis Bacon and Gray’s Inn 212 Bacon and the Drama 217 Bacon as a Poet.. 227 Bacon on Himself 230 Bacon’s Friends and Critics 237 Bacon in the Shadow 259 Bacon as a Cryptographer 267 Appendix 269 Pallas Athene .. 272 Book Notices, Notes, etc. -

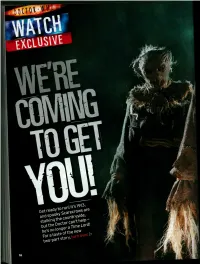

T 1913, I ^ * I No Longer A

XCLUSW-t 1913, ^ * I i no longer a • ' *• • *:• i li • r> . DOCTOR WHO Saturdays BBi DOCTOR WHO CONFIDENTIAL Saturdays THE FINAL STRAW "I'd say this is the scariest creature so far," says Ken Hosking (Scarecrow, far left) - and as a veteran monster-performer, he's well placed to know. "But it only takes about 20 minutes to put on, so it's not one of the more complicated costumes." "It's comfortable to wear because it's soft, not rigid, so you can do lots of action in it," adds Ruari Mears (Scarecrow, centre). "But when you start exerting yourself, ventilation becomes an issue. We've been given breathing ^W exercises by the choreographer." S M" %ff"r^. i*j$L "We breathe in for eight •'1 '~^?um-- seconds, breathe out for eight, breathe in for five, breathe out for F£A 'a eight - that sort of thing," adds •a jfl FJ«L ! 1 Hosking, "just generally varying 1 \ your breathing to slow it down •r~~.' . kd x 3 P \ iff/ consciously, so you don't panic " "*f»pr i and hyperventilate. But it's not f" ^' *^*^ as physically arduous as some of the other monsters have been." Maybe Scarecrow Hosking got -V off lightly - "You didn't have to run up that blooming country lane!" // Mears retorts. For exclusive video clips from our Scarecrow photo shoot, visit www.radiotimes.com/ doctor-who-scarecrows - The Doctor is forced ho regenerator Russell T Davies has flagged this two-parter as "a very human... but he different sort of a story", W isn't safe at all" and he isn't wrong. -

TH256-15 Adapting Shakespeare for Performance

TH256-15 Adapting Shakespeare for Performance 21/22 Department Theatre and Performance Studies Level Undergraduate Level 2 Module leader Ronan Hatfull Credit value 15 Module duration 10 weeks Assessment 100% coursework Study location University of Warwick main campus, Coventry Description Introductory description Adapting Shakespeare for Peformance is a practice-based module that invites students to engage in the adaptation process and produce their own creative responses to the plays of William Shakespeare. This module will challenge students to produce their own interpretation of plays which have helped shape how adaptation is received and practiced. An intrinsic part of Shakespeare’s legacy is the adaptation of his work on stage, page and screen. Shakespeare himself was a consummate adapter, drawing on pre-existing literary and theatrical materials and re-working these for his audiences, for whom his plays were a form of popular entertainment. How is Shakespeare reconceptualised in the context of popular culture and what methods do modern artists use to render his work accessible? This module will challenge the perception of what can be perceived as an adaptation of Shakespeare and each 180-minute workshop will involve practical exploration of different media, including poetry, prose, film, television and theatre. Students will be asked to create a three-minute mini-adaptation/pitch in response to each week’s material and asked to present this at the following seminar. Using this accumulative creative material and case studies as models, the module will culminate with the creation of group adaptations, which will be rehearsed in Weeks 8 and 9 and presented during Week 10. -

The Shakespeare Code in Psalm 46, a Meditation on Shakespeare's Name

July 2016 VOL XXIV, Issue 7, Number 279 Editor: Klaus J. Gerken European Editor: Mois Benarroch Contributing Editor: Jack R. Wesdorp Previous Associate Editors: Igal Koshevoy; Evan Light; Pedro Sena; Oswald Le Winter; Heather Ferguson; Patrick White ISSN 1480-6401 INTRODUCTION Jorge Etcheverry Arcaya Acorn At Orion (Ottawa 1986) CONTENTS Alberto Quero COMING BACK Allan Johnston Song Conversation en Route How to Speak to the Dead Sestina: At A Party Reason and Love Christie-Luke Jones URBAN FOX A CONVOLUTED NIGHTMARE OSLO ae reiff The Shakespeare Code in Psalm 46, a Meditation on Shakespeare's Name SIMON PERCHIK Not yet finished melting :the sun * Again The Times, spread-eagle * Lower and lower this fan * Appearing and disappearing, this gate * These graves listen to you Bruce Wise 5 Tennos Odin's Runic Rhyme by Lars U. Ice Bedew The Vector of the Swan by Sea Curlew Ibed At the City Bus Stop by Bruc "Diesel" Awe The Older Man and the Kid by Rudi E. Welec, "Abs" O, Let the Gods by Luis de Cawebre Mark Young geographies: Puerto Padre Snow Pony seems to trust her A line from James Taylor Superbowl Serendipity Michael Lee Johnson I Regret Grinder, but, No Remorse Ball Jar Old Men Walk Funny Cut Through Thickness (V2) POST SCRIPTUM Jorge Etchverry Arcaya Contract Jorge Etcheverry Arcaya Acorn At Orion (Ottawa 1986) Coughing red faced his eyes a mere line interrupting Marta Flamingo (she was the first reader of the evening) and everybody looked tense waiting for the next cough sure to come Then it was his turn and he started talking about birds more specifically, crows The man was sick everybody could see that sick and drunk At last he said something that I wouldn't try to write in an indirect style He was going to die soon and we had to trust him It was nothing And the host tried to "make light" of things and no one budged an eyelash you could have heard a pin drop I went out alone and he was drinking, seated on the porch. -

Doctor Who and the Politics of Casting Lorna Jowett, University

Doctor Who and the politics of casting Lorna Jowett, University of Northampton Abstract: This article argues that while long-running science fiction series Doctor Who (1963-89; 1996; 2005-) has started to address a lack of diversity in its casting, there are still significant imbalances. Characters appearing in single episodes are more likely to be colourblind cast than recurring and major characters, particularly the title character. This is problematic for the BBC as a public service broadcaster but is also indicative of larger inequalities in the television industry. Examining various examples of actors cast in Doctor Who, including Pearl Mackie who plays companion Bill Potts, the article argues that while steady progress is being made – in the series and in the industry – colourblind casting often comes into tension with commercial interests and more risk-averse decision-making. Keywords: colourblind casting, television industry, actors, inequality, diversity, race, LGBTQ+ 1 Doctor Who and the politics of casting Lorna Jowett The Britain I come from is the most successful, diverse, multicultural country on earth. But here’s my point: you wouldn’t know it if you turned on the TV. Too many of our creative decision-makers share the same background. They decide which stories get told, and those stories decide how Britain is viewed. (Idris Elba 2016) If anyone watches Bill and she makes them feel that there is more of a place for them then that’s fantastic. I remember not seeing people that looked like me on TV when I was little. My mum would shout: ‘Pearl! Come and see. -

Maids and Masters: the Distribution of Power in Doctor Who Series Three

Maids and Masters: The Distribution of Power in Doctor Who Series Three Courtney Stoker is a cisgendered white woman living in the United States. After getting her M.A. in English, she started working as an adjunct instructor to pay for her writing habit. Her research and writing focus on feminism, science fiction and fan studies. She is a bit of an expert on cosplay as a fan practice, particularly femme cosplay in the Doctor Who fan community, and has been interviewed on the subject at io9 and the now- defunct The Sexist. She recently started Doctor Her, a group feminist Doctor Who fan blog (www.doctorher.com). What’s so compelling about the Doctor? Why do so many different kinds of people jump in the TARDIS to travel with him? Is it his boyish SERIES charm, his goodness, his sense of humor? I would argue that for most of the companions in the new series, the most attractive part of the Time Lord is his power. To convince Rose to leave her life for adventure, the ninth Doctor expands on the power he has: “Did I mention that it travels in time?” Later, Martha says to the 3 crowd in the tenement in Last of the Time Lords, “I know what he can do.” That’s her vote of confidence for the Doctor, how she convinces the people of the Doctor’s importance: what he can do, not how good or brave he is. The adventure the Doctor offers his companion is insepara- ble from his power, from his ability to manipulate space and time, from his ability to threaten and fight enemies unimaginably evil and power- ful. -

Much Ado About Nothing

SI Nov. Dec 11_SI new design masters 9/27/11 12:43 PM Page 38 Much Ado about Nothing Anti-Stratfordians start with the answer they want and work backward to the evidence—the opposite of good science and scholarship. They reverse the standards of objective inquiry, replacing them with pseudoscience and pseudohistory. ould a mere commoner have been the greatest and most admired play- wright of the English language? In- Cdeed, could a “near-illiterate” have amassed the “encyclopedic” knowledge that fills page after page of plays and poetry attrib- uted to William Shakespeare of Stratford- upon-Avon? Those known as “anti-Strat - fordians” insist the works were penned by another, one more worthy in their estima- tion, as part of an elaborate conspiracy that may even involve secret messages en- crypted in the text. Now, there are serious, scholarly questions relating to Shakespeare’s authorship, as I learned while doing graduate work at the University of Kentucky and teaching an under- graduate course, Survey of English Literature. For a chapter of my dissertation, I investigated the questioned attribution of the play Pericles to see whether it was a collaborative effort (as some scholars suspected, seeing a disparity in style be- tween the first portion, acts I and II, and the remainder) or—as I found, taking an innovative approach—entirely written by Shakespeare (see Nickell 1987, 82–108). How- ever, such literary analysis is quite different from the efforts of the anti-Stratfordians, who are mostly nonacademics and, according to one critic (Keller 2009, 1–9), “pseudo-scholars.” SI Nov.