UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, IRVINE the Relevance of Black

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dance Theater of Harlem and a Large-Scale Recycling of Rhythms

dance theater of harlem and a large-scale recycling of rhythms. Moreover, the Stolzoff, Norman C. Wake the Town and Tell the People: Dance- philosophical and political ideals featured in many roots hall Culture in Jamaica. Durham, N.C.: Duke University reggae lyrics were initially replaced by “slackness” themes Press, 2000. that highlighted sex rather than spirituality. The lyrical mike alleyne (2005) shift also coincided with a change in Jamaica’s drug cul- ture from marijuana to cocaine, arguably resulting in the harsher sonic nature of dancehall, which was also referred to as ragga (an abbreviation of ragamuffin), in the mid- Dance Theater of 1980s. The centrality of sexuality in dancehall foregrounded arlem ❚❚❚ H lyrical sentiments widely regarded as being violently ho- mophobic, as evidenced by the controversies surrounding The Dance Theater of Harlem (DTH), a classical dance Buju Banton’s 1992 hit, “Boom Bye Bye.” Alternatively, company, was founded on August 15, 1969, by Arthur some academics argue that these viewpoints are articulat- Mitchell and Karel Shook as the world’s first permanent, ed only in specific Jamaican contexts, and therefore should professional, academy-rooted, predominantly black ballet not receive the reactionary condemnation that dancehall troupe. Mitchell created DTH to address a threefold mis- often appears to impose on homosexuals. While dance- sion of social, educational, and artistic opportunity for the hall’s sexual politics have usually been discussed from a people of Harlem, and to prove that “there are black danc- male perspective, the performances of X-rated female DJs, ers with the physique, temperament and stamina, and ev- such as Lady Saw and Patra, have helped redress the gen- erything else it takes to produce what we call the ‘born’ der balance. -

Five Pioneering Black Ballerinas

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Five Pioneering Black Ballerinas: ‘We Have to Have a Voice’ These early Dance Theater of Harlem stars met weekly on Zoom — to survive the isolation of the pandemic and to reclaim their role in dance history. The 152nd Street Black Ballet Legacy, from left: Marcia Sells, Sheila Rohan, Gayle McKinney-Griffith, Karlya Shelton-Benjamin and Lydia Abarca-Mitchell. By Karen Valby June 17, 2021 Last May, adrift in a suddenly untethered world, five former ballerinas came together to form the 152nd Street Black Ballet Legacy. Every Tuesday afternoon, they logged onto Zoom from around the country to remember their time together performing with Dance Theater of Harlem, feeling that magical turn in early audiences from skepticism to awe. Life as a pioneer, life in a pandemic: They have been friends for over half a century, and have held each other up through far harder times than this last disorienting year. When people reached for all manners of comfort, something to give purpose or a shape to the days, these five women turned to their shared past. In their cozy, rambling weekly Zoom meetings, punctuated by peals of laughter and occasional tears, they revisited the fabulousness of their former lives. With the 2 background of George Floyd’s murder and a pandemic disproportionately affecting the Black community, the women set their sights on tackling another injustice. They wanted to reinscribe the struggles and feats of those early years at Dance Theater of Harlem into a cultural narrative that seems so often to cast Black excellence aside. “There’s been so much of African American history that’s been denied or pushed to the back,” said Karlya Shelton-Benjamin, 64, who first brought the idea of a legacy council to the other women. -

Dance Theatre of Harlem

François Rousseau François DANCE THEATRE OF HARLEM Founders Arthur Mitchell and Karel Shook Artistic Director Virginia Johnson Executive Director Anna Glass Ballet Master Kellye A. Saunders Interim General Manager Melinda Bloom Dance Artists Lindsey Croop, Yinet Fernandez, Alicia Mae Holloway, Alexandra Hutchinson, Daphne Lee, Crystal Serrano, Ingrid Silva, Amanda Smith, Stephanie Rae Williams, Derek Brockington, Da’Von Doane, Dustin James, Choong Hoon Lee, Christopher Charles McDaniel, Anthony Santos, Dylan Santos, Anthony V. Spaulding II Artistic Director Emeritus Arthur Mitchell PROGRAM There will be two intermissions. Friday, March 1 @ 8 PM Saturday, March 2 @ 2 PM Saturday, March 2 @ 8 PM Zellerbach Theatre The 18/19 dance series is presented by Annenberg Center Live and NextMove Dance. Support for Dance Theatre of Harlem’s 2018/2019 professional Company and National Tour activities made possible in part by: Anonymous; The Arnhold Foundation; Bloomberg Philanthropies; The Dauray Fund; Doris Duke Charitable Foundation; Elephant Rock Foundation; Ford Foundation; Ann & Gordon Getty Foundation; Harkness Foundation for Dance; Howard Gilman Foundation; The Dubose & Dorothy Heyward Memorial Fund; The Klein Family Foundation; John L. McHugh Foundation; Margaret T. Morris Foundation; National Endowment for the Arts; New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew M. Cuomo and the New York State Legislature; New England Foundation for the Arts, National Dance Project; Tatiana Piankova Foundation; May and Samuel Rudin -

Black Dance Stories Presents All-New Episodes Featuring Robert

Black Dance Stories Presents All-New Episodes Featuring Robert Garland & Tendayi Kuumba (Apr 8), Amy Hall Garner & Amaniyea Payne (Apr 15), NIC Kay & Alice Sheppard (Apr 22), Christal Brown & Edisa Weeks (Apr 29) Thursdays at 6pm EST View Tonight’s Episode Live on YouTube at 6pm EST Robert Battle and Angie Pittman Episode Available Now (Brooklyn, NY/ March 8, 2021) – Black Dance Stories will present new episodes in April featuring Black dancers, choreographers, movement artists, and creatives who use their work to raise societal issues and strengthen their community. This month the dance series brings together Robert Garland & Tendayi Kuumba (Apr 8), Amy Hall Garner & Amaniyea Payne (Apr 15), NIC Kay & Alice Sheppard (Apr 22), Christal Brown & Edisa Weeks (Apr 29), and Robert Battle & Angie Pittman (Apr 1). The incomparable Robert Garland (Dance Theatre of Harlem) and renaissance woman Tendayi Kuumba (American Utopia) will be guests on an all-new episode of Black Dance Stories tonight, Thursday, April 8 at 6pm EST. Link here. Robert Battle, artistic director of Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, and Angie Pittman, Bessie award- winning dancer, joined the Black Dance Stories community on April 1. In the episode, they talk about (and sing) their favorite hymens, growing up in the church, and the importance of being kind. During the episode, Pittman has a full-circle moment when she shared with Battle her memory of meeting him for the first time and being introduced to his work a decade ago. View April 1st episode here. Conceived and co-created by performer, producer, and dance writer Charmaine Warren, the weekly discussion series showcases and initiates conversations with Black creatives that explore social, historical, and personal issues and highlight the African Diaspora's humanity in the mysterious and celebrated dance world. -

For Immediate Release April 4, 2013

Presented by Dance Affiliates and the Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts For Immediate Release April 4, 2013 Media Contact Sarah Fergus Dance Affiliates—Community Outreach Marketing and Communications Manager Anne-Marie Mulgrew Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts Director, Education & Special Projects 215.573.8537 215.636.9000 ext.110 [email protected] [email protected] Hi-res images available at AnnenbergCenter.org/press. Dance Theatre of Harlem makes its highly anticipated return to the Philadelphia stage Rock School alum and featured dancer in the documentary First Position Michaela DePrince is featured Philadelphia’s Robert Garland continues with the company as Resident Choreographer (Philadelphia, April 4, 2013)—The newly relaunched Dance Theatre of Harlem (DTH) makes its return to the dance world and Philadelphia after an eight-year hiatus with an eclectic mix of new and familiar works that highlight the range and diversity of this legendary company. Among the world’s foremost interpreters of the Balanchine canon, the company has garnered critical acclaim for history-making productions and returns in full force under the artistic direction of founding member and longtime prima ballerina, Virginia Johnson. This production wraps up Dance Celebration’s 30th anniversary season, presented by Dance Affiliates and the Annenberg Center. Performances take place at the Annenberg Center, 3680 Walnut Street, on Thursday, May 16 at 7:30 PM; Friday, May 17 at 8 PM*; Saturday, May 18 at 2 PM and 8 PM; and Sunday, May 19 at 3 PM. Tickets are $20-$75 (prices are subject to change). For tickets or for more information, please visit AnnenbergCenter.org or call 215.898.3900. -

Beyond the Machine 21.0

Beyond the Machine 21.0 The Juilliard School presents Center for Innovation in the Arts Edward Bilous, Founding Director Beyond the Machine 21.0: Emerging Artists and Art Forms New works by composers, VR artists, and performers working with new performance technologies Thursday, May 20, 2021, 7:30pm ET Saturday, May 22, 2021, 2 and 7pm ET Approximate running time: 90 minutes Juilliard’s livestream technology is made possible by a gift in honor of President Emeritus Joseph W. Polisi, building on his legacy of broadening Juilliard’s global reach. Juilliard is committed to the diversity of our community and to fostering an environment that is inclusive, supportive, and welcoming to all. For information on our equity, diversity, inclusion, and belonging efforts, and to see Juilliard's land acknowledgment statement, please visit our website at juilliard.edu. 1 About Emerging Artists and Art Forms The global pandemic has compelled many performing artists to explore new ways of creating using digital technology. However, for students studying at the Center for Innovation in the Arts, working online and in virtual environments is a normal extension of daily classroom activities. This year, the Center for Innovation in the Arts will present three programs featuring new works by Juilliard students and alumni developed in collaboration with artists working in virtual reality, new media, film, and interactive technology. The public program, Emerging Artists and Artforms, is a platform for students who share an interest in experimental art and interdisciplinary collaboration. All the works on this program feature live performances with interactive visual media and sound. -

Mccarter THEATRE CENTER FOUNDERS Arthur Mitchell Karel

McCARTER THEATRE CENTER William W. Lockwood, Jr. Michael S. Rosenberg SPECIAL PROGRAMMING DIRECTOR MANAGING DIRECTOR presents FOUNDERS Arthur Mitchell Karel Shook ARTISTIC DIRECTOR EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Virginia Johnson Anna Glass BALLET MASTER INTERIM GENERAL MANAGER Marie Chong Melinda Bloom DANCE ARTISTS Lindsey Donnell, Yinet Fernandez, Alicia Mae Holloway, Alexandra Hutchinson, Daphne Lee, Crystal Serrano, Ingrid Silva, Amanda Smith, Stephanie Rae Williams, Derek Brockington, Kouadio Davis, Da’Von Doane, Dustin James, Choong Hoon Lee, Christopher McDaniel, Sanford Placide, Anthony Santos, Dylan Santos ARTISTIC DIRECTOR EMERITUS Arthur Mitchell Please join us after this performance for a post-show conversation with Artistic Director Virginia Johnson. SATURDAY, FEBRUARY 8, 2020 The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment of any kind during performances is strictly prohibited. Support for Dance Theatre of Harlem’s 2019/2020 professional Company and National Tour activities made possible in part by: Anonymous, The Arnhold Foundation; Bloomberg Philanthropies, The Dauray Fund; Doris Duke Charitable Foundation; Elephant Rock Foundation; Ford Foundation; Ann & Gordon Getty Foundation; Harkness Foundation for Dance; Howard Gilman Foundation; The Dubose & Dorothy Heyward Memorial Fund; The Klein Family Foundation; John L. McHugh Foundation; Margaret T. Morris Foundation; National Endowment for the Arts, New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew M. Cuomo and the New York State Legislature; New England -

Dance Theatre of Harlem Returns to the Auditorium Theatre November 1820 View in Browser

10/11/2016 Auditorium Theatre Dance Theatre of Harlem Returns to the Auditorium Theatre November 1820 View in browser 50 E Congress Pkwy Lily Oberman Chicago, IL 312.341.2331 (office) | 973.699.5312 (cell) AuditoriumTheatre.org [email protected] Release date: October 11, 2016 Dance Theatre of Harlem Returns to the Auditorium Theatre November 1820 Company presents Midwest premiere of Francesca Harper's System The acclaimed Dance Theatre of Harlem (DTH) gives three performances at the Auditorium Theatre on November 18, 19, and 20 with a program that includes System, a major new work by choreographer Francesca Harper. The work is supported by the New England Foundation for the Arts, and is inspired by the current social, political, and economic climate in the United States. System was choreographed in collaboration with Dance Theatre of Harlem dancers who used their own experiences as people of color for inspiration. DTH Artistic Director Virginia Johnson told the Washington Post that System “addresses social justice issues in the Black Lives Matter era” and is “a very contemporary piece, but also very beautiful and uplifting." A live string quartet performs composer John Adams’ original music for the piece. “Dance Theatre of Harlem’s Midwest premiere of System is relevant, timely, and connected to current events happening around the country, especially right here in Chicago,” says Auditorium Theatre CEO Tania Castroverde Moskalenko. “We are honored to present this powerful work at the Auditorium, and know that it will have an impact on all those who experience it." The company also performs Brahms Variations, a new neoclassical ballet by Dance Theatre of Harlem’s Resident Choreographer Robert Garland set to Johannes Brahms’ “Variations on a Theme by Joseph Haydn,” and Coming Together, the 1991 work by Spanish choreographer Nacho Duato. -

2019-2020 Season Overview JULY 2020

® 2019-2020 Season Overview JULY 2020 Report Summary The following is a report on the gender distribution of choreographers whose works were presented in the 2019-2020 seasons of the fifty largest ballet companies in the United States. Dance Data Project® separates metrics into subsections based on program, length of works (full-length, mixed bill), stage (main stage, non-main stage), company type (main company, second company), and premiere (non-premiere, world premiere). The final section of the report compares gender distributions from the 2018- 2019 Season Overview to the present findings. Sources, limitations, and company are detailed at the end of the report. Introduction The report contains three sections. Section I details the total distribution of male and female choreographic works for the 2019-2020 (or equivalent) season. It also discusses gender distribution within programs, defined as productions made up of full-length or mixed bill works, and within stage and company types. Section II examines the distribution of male and female-choreographed world premieres for the 2019-2020 season, as well as main stage and non-main stage world premieres. Section III compares the present findings to findings from DDP’s 2018-2019 Season Overview. © DDP 2019 Dance DATA 2019 - 2020 Season Overview Project] Primary Findings 2018-2019 2019-2020 Male Female n/a Male Female Both Programs 70% 4% 26% 62% 8% 30% All Works 81% 17% 2% 72% 26% 2% Full-Length Works 88% 8% 4% 83% 12% 5% Mixed Bill Works 79% 19% 2% 69% 30% 1% World Premieres 65% 34% 1% 55% 44% 1% Please note: This figure appears inSection III of the report. -

Michael Langlois

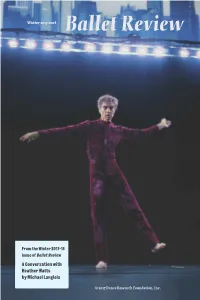

Winter 2 017-2018 B allet Review From the Winter 2017-1 8 issue of Ballet Review A Conversation with Heather Watts by Michael Langlois © 2017 Dance Research Foundation, Inc. 4 New York – Elizabeth McPherson 6 Washington, D.C. – Jay Rogoff 7 Miami – Michael Langlois 8 Toronto – Gary Smith 9 New York – Karen Greenspan 11 Paris – Vincent Le Baron 12 New York – Susanna Sloat 13 San Francisco – Rachel Howard 15 Hong Kong – Kevin Ng 17 New York – Karen Greenspan 19 Havana – Susanna Sloat 46 20 Paris – Vincent Le Baron 22 Jacob’s Pillow – Jay Rogoff 24 Letter to the Editor Ballet Review 45.4 Winter 2017-2018 Lauren Grant 25 Mark Morris: Student Editor and Designer: Marvin Hoshino and Teacher Managing Editor: Joel Lobenthal Roberta Hellman 28 Baranovsky’s Opus Senior Editor: Don Daniels 41 Karen Greenspan Associate Editors: 34 Two English Operas Joel Lobenthal Larry Kaplan Claudia Roth Pierpont Alice Helpern 39 Agon at Sixty Webmaster: Joseph Houseal David S. Weiss 41 Hong Kong Identity Crisis Copy Editor: Naomi Mindlin Michael Langlois Photographers: 46 A Conversation with Tom Brazil 25 Heather Watts Costas Associates: Joseph Houseal Peter Anastos 58 Merce Cunningham: Robert Gres kovic Common Time George Jackson Elizabeth Kendall Daniel Jacobson Paul Parish 70 At New York City Ballet Nancy Reynolds James Sutton Francis Mason David Vaughan Edward Willinger 22 86 Jane Dudley on Graham Sarah C. Woodcock 89 London Reporter – Clement Crisp 94 Music on Disc – George Dorris Cover photograph by Tom Brazil: Merce Cunningham in Grand Central Dances, Dancing in the Streets, Grand Central Terminal, NYC, October 9-10, 1987. -

Houston Ballet 2014-2015 Annual Report

Annual Report 2014 - 2015 BOARD OF TRUSTEES CHAIRMAN Mr. James M. Jordan PRESIDENT Mrs. Phoebe Tudor SECRETARY Mission Statement Mrs. Margaret Alkek Williams OFFICERS Ms. Leticia Loya, VP – Academy Mr. James M. Nicklos, VP – Finance To inspire a lasting love and appreciation for dance through artistic excellence, Mr. Joseph A. Hafner, Jr., VP – Institutional Giving Mr. Daniel M. McClure, VP – Investments exhilarating performances, innovative choreography and Mrs. Becca Cason Thrash, VP – Special Events Mrs. Donald M. Graubart, VP – Trustee Development superb educational programs MEMBERS-AT-LARGE In furtherance of our mission, we are committed to maintaining and enhancing our status as: Ms. Michelle Baden Mrs. F. T. Barr Mrs. Kristy Junco Bradshaw • A classically trained company with a diverse repertory whose range Mrs. J. Patrick Burk Mrs. Lenore K. Burke includes the classics as well as contemporary works. Mrs. Albert Y. Chao Mr. Jesse H. Jones II Mrs. Henry S. May, Jr. • A company that attracts the world’s best dancers and choreographers Mr. Richard K. McGee and provides them with an environment where they can thrive and Mrs. Michael Mithoff Mr. Michael S. Parmet further develop the art form. Mrs. Carroll Robertson Ray Mr. Karl S. Stern Mr. Nicholas L. Swyka • An international company that is accessible to broad and growing local, Mrs. Allison Thacker national, and international audiences. Mrs. Oscar S. Wyatt, Jr. TRUSTEES • A company with a world-class Academy that provides first rate Mrs. Kristen Andreasen Mrs. Richard E. Fant Hon. Mica Mosbacher Mr. Cecil H. Arnim III Mrs. Claire S. Farley Ms. Beth Muecke instruction for professional dancers and meaningful programs for non- Mrs. -

Black-Ballerina-Discussion-Guide.Pdf

1 WHAT’S MISSING? A STUDY AND DISCUSSION GUIDE FOR BLACK BALLERINA What’s Missing? The documentary film BLACK BALLERINA tells the story of several black women from different generations who fell in love with ballet. Six decades ago, Joan Myers Brown, Delores Browne, and Raven Wilkinson faced racism in their pursuit of careers in classical ballet. Today, young dancers of color continue to face formidable challenges breaking into the overwhelmingly white world of ballet. Moving back and forth in time, this lyrical, character-driven film presents a fresh discussion about race, inclusion, and opportunity across all sectors of American society. ___________________ WHAT IS CLASSICAL BALLET? What is known today as classical ballet began in the “...When a disgruntled military attempted at royal courts of France and developed through the noble houses one point to install a monarchy with George of the Italian Renaissance. In the 15th century, noblemen and Washington as king, he fiercely resisted.” women attended lavish dinners, especially wedding celebrations, Wilf Hey, “George Washington: The Man where dancing and music created elaborate spectacles. Dancing Who Would Not Be King,” 2000 masters taught the steps to the nobility and the court participated in the performances. In the 16th century, Catherine de Medici— an Italian noblewoman, wife of King Henry II of France, and a great patron of the arts—began to fund ballet in the French court. A century later, King Louis XIV helped to popularize and standardize the new art form. A devoted dancer, he performed many roles. His love of ballet led to its development from a party activity for members of the court to becoming a practice requiring disciplined professional training.