Jobs and the Climate Stewardship Act: How Curbing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1971 in the United States Wikipedia 1971 in the United States from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

4/30/2017 1971 in the United States Wikipedia 1971 in the United States From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Events from the year 1971 in the United States. Contents 1 Incumbents 1.1 Federal Government 1.2 Governors 1.3 Lieutenant Governors 2 Events 2.1 January 2.2 February 2.3 March 2.4 April 2.5 May 2.6 June 2.7 July 2.8 August 2.9 September 2.10 October 2.11 November 2.12 December 2.13 Undated 2.14 Ongoing 3 Births 3.1 January 3.2 February 3.3 March 3.4 April 3.5 May 3.6 June 3.7 July 3.8 August 3.9 September 3.10 October 3.11 November 3.12 December 4 Deaths 5 See also 6 References 7 External links Incumbents Federal Government https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1971_in_the_United_States 1/13 4/30/2017 1971 in the United States Wikipedia President: Richard Nixon (RCalifornia) Vice President: Spiro Agnew (RMaryland) Chief Justice: Warren E. Burger (Minnesota) Speaker of the House of Representatives: John William McCormack (DMassachusetts) (until January 3), Carl Albert (DOklahoma) (starting January 21) Senate Majority Leader: Mike Mansfield (DMontana) Congress: 91st (until January 3), 92nd (starting January 3) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1971_in_the_United_States 2/13 4/30/2017 1971 in the United States Wikipedia Governors and Lieutenant Governors Governors Governor of Alabama: Albert Brewer Governor of Maryland: Marvin Mandel (Democratic) (until January 18), George (Democratic) Wallace (Democratic) (starting January 18) Governor of Massachusetts: Francis W. Governor of Alaska: William A. -

Annual Report July 1, 2008-June 30, 2009

ROSE FITZGERALD KENNEDY GREENWAY CONSERVANCY ANNUAL REPORT JULY 1, 2008-JUNE 30, 2009 _______________________________________________________________ CONTENTS: PAGE: Key Accomplishments ………………………………………………………. 1 Summary of Financial Statements …………………………………………. 3 Donors ………………………………………………………………………... 4 Conservancy Staff ………………………………………………………..….. 15 Board of Directors and Leadership Council …………….………………... 16 Audited Financial Statements ……………………………………… Addendum KEY ACCOMPLISHMENTS The Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy Greenway (“the Greenway”) is one of the largest and most important public projects in Boston’s history, and it is just beginning to realize its full potential. A Greenway “district” is emerging, with more cafés, retail stores, entertaining and educational attractions, and new investments in properties adjacent to the Greenway. The Greenway itself is an integral part of this evolution, expressing the best of Boston though horticulture and the arts. As the steward of the Greenway, the Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy Greenway Conservancy (“the Conservancy”) has been working to achieve a shared vision of the Greenway as a physical and civic connector. The Conservancy is proud to present an overview of our accomplishments for the past year in the areas of park operations, public programs, fundraising and support. PARK OPERATIONS Inspired by the life of Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy, the Conservancy’s approach to everything we do blends the practical with the principled. To support public health and maintain the newly restored water quality in Boston Harbor, our park operations staff (five positions) has made a commitment to use methods and products that are environmentally responsible and avoid the use of toxic chemicals. The park maintenance team has grown to include individuals with disabilities, subcontracted from Work, Inc., and soon will incorporate Boston teens and young adults through the Conservancy’s Green and Grow youth workforce development program. -

One Voice United

2015 ANNUAL REPORT ONE VOICE UNITED 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Letter from the ADPAC Chairman On behalf of the American Dental Political Action Committee (ADPAC), I am pleased to present the 2015 Annual Report. Letter from the ADPAC Chairman........................2 Raising Money.............................................................3 ADPAC has four main functions: Receipts....................................................3 Disbursements........................................3 $ ADPAC Philosophy of Giving...................................3 Distributing Contributions – Raise Distribute Political Grassroots 2015 ADPAC Disbursements to money contributions education advocacy Incumbents and Candidates....................................4 All these functions are important, but if we are not raising the money, we are not able to carry on other functions. State Dentist Legislator Tracking...........................6 Because of the generous financial support of our members, we’ve been able to help educate and elect thousands of Dentists in Congress..................................................7 candidates across the country who want to make a difference. Thank you! Grassroots Advocacy................................................8 American Dental Association This report tells a great story about the power of our political engagement efforts. The PAC’s role is to support dentistry, Independent Expenditures (IEs)...........................10 protect your business, advance oral health, empower our members and inspire Congress to act. This -

Éliane Radigue's Collaborative Creative Process William

Imagining Together: Éliane Radigue’s Collaborative Creative Process William Dougherty Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2021 © 2021 William Dougherty All Rights Reserved Abstract Imagining Together: Éliane Radigue’s Collaborative Creative Process William Dougherty This dissertation examines Éliane Radigue’s collaborative compositional practice as an alternative model of creation. Using normative Western classical music mythologies as a backdrop, this dissertation interrogates the ways in which Radigue’s creative practice calls into question traditional understandings of creative agency, authorship, reproduction, performance, and the work concept. Based on extensive interviews with the principal performer-collaborators of Radigue’s early instrumental works, this dissertation retraces the networks and processes of creation—from the first stages of the initiation process to the transmission of the fully formed composition to other instrumentalists. In doing so, I aim to investigate the ways in which Radigue’s unique working method resists capitalist models of commodification and reconfigures the traditional hierarchical relationship between composer, score, and performer. Chapter 1 traces Radigue’s early experiences with collaboration and collective creativity in the male-dominated early electronic music studios of France in the 1950s and 60s. Chapter 2 focuses on the initiation process behind new compositions. Divided into two parts, the first part describes the normative classical music-commissioning model (NCMCM) using contemporary guides for composers and commissioners and my own experiences as an American composer of concert music. The second part examines Radigue’s performer-based commissioning model and illuminates how this initiation process resists power structures of the NCMCM. -

Albert S. Miller Takes Two of His Force As Partners Scotch Labor Day

AH the Newi of SECTION BED DANK and Surrounding Towni Told Fearleisly and Without BU* RED BANK TER ONE Iiaued Wsekly, entered BI Second-Class Mutter at the Pt>Bt- Sill)! rrlption Prlre: On* Year 12.00, VOLUME LIX, NO. 11. o flic a at Red Hank, N. J., urn) >r thi Act of March 8, IS 19. RED BANK, N. J., THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 3, 1936. Six Months, 11.00, Single cop?1. 4c. PAGES 1 TO 12. TAKES PARTNERS Makes Protest Retired Business PASSED ON Albert S. Miller About Insurance And Financial Scotch Labor Day * Before Council Man Passes On Takes Two of His Dennis K. Byrne Tells Rumson Marcus M. Davidson Died Sun- Reunion and Field Officials Municipal Insurance day Morning at His Home of Business Should be Awarded Complications in His 76th Force As Partners on the Pro Rata Basis. Year—Funeral Tuesday. Games at Holmdel Criticism of the manner in which Marcus M. Davidson, one of Red tho insurance business of the Hum-Bank's best known residents, passed Marie C Riordari United Scottish Clans and New Firm Includes His Son, William A. Miller, and eon borough council is handled was away at his homo on Leroy place expressed at the regular meeting of shortly before noon Sunday from a Daughters of Scotia of Benjamin A. Crate—Change Will Not Affect the mayor and council Thursday complication of diseases in his 76th New Postmaster night by Dennis K. Byrne, real es- year. He had been in failing health for several months but his condition New Jersey to Have Big Sales Force or Business Methods. -

Full 2016 Annual Report

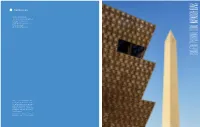

SMITHSONIAN Smithsonian Institution Office of Advancement 1000 Jefferson Drive S.W., 4th floor MRC 035, P.O. Box 37012 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 Phone: 202.633.4300 REPORT ANNUAL 2016 smithsoniancampaign.org Front cover: The National Museum of African American History and Culture, the Smithsonian’s 19th museum, stands on the National Mall adjacent to the Washington Monument. Read about its Sept. 24, 2016, dedication and opening inside this report. View the 2016 Smithsonian annual report, with added content, at si.edu/annualreport. CONTENTS Secretary’s Letter 2 A Moment for the Nation 4 Thought Leaders 12 Endless Discovery 20 You Build It 26 2016 by the Numbers 32 Recognition and Reports 34 View this report online, with added content, at si.edu/annualreport. This year, as every year, was a period of change, innovation and great progress for the Smithsonian. Among many accomplish- ments, we marked an extraordinary milestone, decades in the making: the opening of the National Museum of African American History and Culture. This breathtaking museum gives proper place, now and forever, to a vital part of America’s story. The new museum is a significant com- At the Smithsonian, we ask the biggest ponent of the national Smithsonian questions—Where do we come from? Campaign. In fact, in fiscal 2016 we sur- How do we live together? Where will we passed our ambitious $1.5 billion goal with go from here?—and seek answers from one year still to go. More than 480,000 artists, scientists and historians. Our donors and counting have enabled our sci- scholars are passionate about their work, entists, educators and curators to create as illustrated in these pages. -

Digest of Other White House Announcements December 31, 2010

Administration of Barack H. Obama, 2010 Digest of Other White House Announcements December 31, 2010 The following list includes the President's public schedule and other items of general interest announced by the Office of the Press Secretary and not included elsewhere in this Compilation. January 1 In the morning, in Kailua, HI, the President had an intelligence briefing. January 2 In the morning, the President had an intelligence briefing. January 3 In the evening, the President, Mrs. Obama, and their daughters Sasha and Malia returned to Washington, DC, arriving the following morning. January 4 In the afternoon, the President had an intelligence briefing. Later, in the Oval Office, he met with Homeland Security and Counterterrorism Adviser John O. Brennan to discuss the reviews of terrorist watch list procedures and airport security detection capabilities and counterterrorism efforts. January 5 In the morning, in the Oval Office, the President and Vice President Joe Biden had an intelligence briefing. Later, in the Roosevelt Room, they had an economic briefing. Then, in the Oval Office, he met with his senior advisers. In the afternoon, in the Situation Room, the President and Vice President Biden met with Federal agency and department heads and national security advisers to discuss the reviews of terrorist watch list procedures and airport security detection capabilities, intelligence sharing improvements, and counterterrorism efforts. Later, in the Oval Office, they met with Secretary of Defense Robert M. Gates. Then, also in the Oval Office, they met with House of Representatives and Senate Democratic leaders. January 6 In the morning, in the Oval Office, the President and Vice President Joe Biden had an intelligence briefing followed by an economic briefing. -

Working for Water: Governor Richard F. Kneip and the Oahe Irrigation Project

Copyright © 2009 by the South Dakota State Historical Society. All Rights Reserved. JOHN ANDREWS Working for Water Governor Richard F. Kneip and the Oahe Irrigation Project Richard Francis Kneip—the energetic wholesale dairy equipment salesman from Salem—served as governor of South Dakota from 1971 to 1978. He campaigned against Republican incumbent Frank Farrar in 1970 on a platform that included tax reform and improved manage- ment of state government. Those issues came to define Kneip’s admin- istration. Only the sixth Democrat in the state’s history to hold the of- fice, he led a massive overhaul of the executive branch, reducing the number of departments, boards, and agencies from 160 to just sixteen and creating the cabinet style of government in place today. Kneip was not as successful on tax reform. He spearheaded annual efforts in the legislature to create a state income tax, seeking to reduce a burden on property owners that he believed was unfair. He nearly achieved his goal in 1973, but his plan fell one vote short. As the decade progressed, Kneip dealt with more controversial is- sues. The rise of the American Indian Movement, the takeover of Wounded Knee, and the ongoing discord between Indians and non- Indians is well documented. A less well-known issue, but contentious nonetheless, was the fight over the Oahe Irrigation Project. Kneip sup- ported Oahe and worked closely with South Dakota’s congressional delegation, particularly Senator George McGovern, to keep the proj- ect moving. Opponents, largely small family farmers whose land would be used for pipelines and canals, continued to grow until they played a significant role in determining Oahe policy. -

Dear Sharon Foley Bushor, City Councilor, Ward 1, Kevin Worden

Dear Sharon Foley Bushor, City Councilor, Ward 1, Kevin Worden, City Councilor, Ward 1, Jane Knodell, City Councilor, Ward 2, Max Tracy, City Councilor, Ward 2, Vince Brennan, City Councilor, Ward 3, Rachel Siegel, City Councilor, Ward 3, David Hartnett, City Councilor, Ward 4, Bryan Aubin, City Councilor, Ward 4, Joan Shannon, City Councilor, Ward 5, William "Chip" Mason, City Councilor, Ward 5, Norman Blais, City Councilor, Ward 6, Karen Paul, City Councilor, Ward 6, Tom Ayres, City Councilor, Ward 7, and Paul Decelles, City Councilor, Ward 7, We are pleased to present you with this petition affirming this statement: "We urge the Burlington City Council to support the resolution to bar the basing of F-35 Warplanes at Burlington International Airport. " Attached is a list of individuals who have added their names to this petition, as well as additional comments written by the petition signers themselves. Sincerely, Thomas Grace 1 Richard Knittel Versailles, KY 40383 Oct 7, 2013 Peter M. Armour Putney, VT 05346 Oct 7, 2013 Howard McCoy Centreville, MD 21617 Oct 7, 2013 anamaria bermeo Bellflower, CA 90706 Oct 7, 2013 M. United States 85308-4962 Oct 7, 2013 steve ferguson matthews, NC 28104 Oct 7, 2013 Maria Puglisi Randolph, VT 05060 Oct 7, 2013 Peter Caman Littleton, NH 03561 Oct 7, 2013 Danelle McCombs Santa Barbara, CA 93103 Oct 7, 2013 Lauren Dentzman Lemont, IL 60439 Oct 7, 2013 Caleb Drake Oak Park, IL 60304 Oct 7, 2013 Hilary Best Ashland, OR 97520 Oct 7, 2013 2 The US already has 1,000 military bases throughout the world, another one at Burlington is obscene.