Registry Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Addendum No. 3(4)

( 1 ) No. 3 (4).] (Sixth Parliament - Second Session) ADDENDUM TO THE ORDER BOOK No. 3 OF PARLIAMENT Issued on Friday, June 15, 2007 NOTICES OF MOTIONS FOR WHICH NO DATES HAVE BEEN FIXED P.43/’07. Hon. Lakshman Kiriella Hon. Lakshman Senewiratne Hon. Dayasiri Jayasekara Hon. Palitha Range Bandara,— Select Committee of Parliament to look into and recommend steps to be taken to prevent the recent increasing of the abductions of persons— Whereas abductions appear to have become a common daily occurrence in Colombo; And whereas abductions are now taking place in Mahanuwara; And whereas many of these abductions are taking place in broad daylight; And whereas over a hundred persons have been abducted in the past two years alone; And whereas the motives behind these abductions appear to be both political and criminal (extortion of money); And whereas the law enforcement machinery has not taken meaningful steps to prevent these abductions or trace the abductees after the event; And whereas very often the abductees turn up as corpses; And whereas the Police have not been able to trace the killers of the Member of Parliament Mr. N. Raviraj killed in Colombo in broad daylight on a busy city highway; And whereas as recently as June 2007 two Red Cross members (Katikesu Chandramohan and Sinnarasa Shanmugalingam) were abducted from the Fort Railway Station in the presence of hundreds of commuters and two days later their corpses turned up in the Ratnapura District; ( 2 ) And whereas a fear psychosis in gripping the nation and spreading panic and alarm -

Minutes of Parliament Present

(Ninth Parliament - First Session) No. 62.] MINUTES OF PARLIAMENT Thursday, March 25, 2021 at 10.00 a.m. PRESENT : Hon. Mahinda Yapa Abeywardana, Speaker Hon. Angajan Ramanathan, Deputy Chairperson of Committees Hon. Mahinda Amaraweera, Minister of Environment Hon. Dullas Alahapperuma, Minister of Power Hon. Mahindananda Aluthgamage, Minister of Agriculture Hon. Udaya Gammanpila, Minister of Energy Hon. Dinesh Gunawardena, Minister of Foreign and Leader of the House of Parliament Hon. (Dr.) Bandula Gunawardana, Minister of Trade Hon. Janaka Bandara Thennakoon, Minister of Public Services, Provincial Councils & Local Government Hon. Nimal Siripala de Silva, Minister of Labour Hon. Vasudeva Nanayakkara, Minister of Water Supply Hon. (Dr.) Ramesh Pathirana, Minister of Plantation Hon. Johnston Fernando, Minister of Highways and Chief Government Whip Hon. Prasanna Ranatunga, Minister of Tourism Hon. C. B. Rathnayake, Minister of Wildlife & Forest Conservation Hon. Chamal Rajapaksa, Minister of Irrigation and State Minister of National Security & Disaster Management and State Minister of Home Affairs Hon. Gamini Lokuge, Minister of Transport Hon. Wimal Weerawansa, Minister of Industries Hon. (Dr.) Sarath Weerasekera, Minister of Public Security Hon. M .U. M. Ali Sabry, Minister of Justice Hon. (Dr.) (Mrs.) Seetha Arambepola, State Minister of Skills Development, Vocational Education, Research and Innovation Hon. Lasantha Alagiyawanna, State Minister of Co-operative Services, Marketing Development and Consumer Protection ( 2 ) M. No. 62 Hon. Ajith Nivard Cabraal, State Minister of Money & Capital Market and State Enterprise Reforms Hon. (Dr.) Nalaka Godahewa, State Minister of Urban Development, Coast Conservation, Waste Disposal and Community Cleanliness Hon. D. V. Chanaka, State Minister of Aviation and Export Zones Development Hon. Sisira Jayakody, State Minister of Indigenous Medicine Promotion, Rural and Ayurvedic Hospitals Development and Community Health Hon. -

Minutes of Parliament Present

(Eighth Parliament - First Session) No. 134. ] MINUTES OF PARLIAMENT Tuesday, December 06, 2016 at 9.30 a. m. PRESENT : Hon. Karu Jayasuriya, Speaker Hon. Thilanga Sumathipala, Deputy Speaker and Chairman of Committees Hon. Ranil Wickremesinghe, Prime Minister and Minister of National Policies and Economic Affairs Hon. (Mrs.) Thalatha Atukorale, Minister of Foreign Employment Hon. Wajira Abeywardana, Minister of Home Affairs Hon. John Amaratunga, Minister of Tourism Development and Christian Religious Affairs and Minister of Lands Hon. Mahinda Amaraweera, Minister of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources Development Hon. (Dr.) Sarath Amunugama, Minister of Special Assignment Hon. Gayantha Karunatileka, Minister of Parliamentary Reforms and Mass Media and Chief Government Whip Hon. Ravi Karunanayake, Minister of Finance Hon. Akila Viraj Kariyawasam, Minister of Education Hon. Lakshman Kiriella, Minister of Higher Education and Highways and Leader of the House of Parliament Hon. Mano Ganesan, Minister of National Co-existence, Dialogue and Official Languages Hon. Daya Gamage, Minister of Primary Industries Hon. Dayasiri Jayasekara, Minister of Sports Hon. Nimal Siripala de Silva, Minister of Transport and Civil Aviation Hon. Palany Thigambaram, Minister of Hill Country New Villages, Infrastructure and Community Development Hon. Duminda Dissanayake, Minister of Agriculture Hon. Navin Dissanayake, Minister of Plantation Industries Hon. S. B. Dissanayake, Minister of Social Empowerment and Welfare ( 2 ) M. No. 134 Hon. S. B. Nawinne, Minister of Internal Affairs, Wayamba Development and Cultural Affairs Hon. Gamini Jayawickrama Perera, Minister of Sustainable Development and Wildlife Hon. Harin Fernando, Minister of Telecommunication and Digital Infrastructure Hon. A. D. Susil Premajayantha, Minister of Science, Technology and Research Hon. Sajith Premadasa, Minister of Housing and Construction Hon. -

Preferential Votes

DN page 6 SATURDAY, AUGUST 8, 2020 GENERAL ELECTION PREFERENTIAL VOTES Samagi Jana Balawegaya (SJB) Duminda Dissanayake 75,535 COLOMBO DISTRICT H. Nandasena 53,618 Rohini Kumari Kavirathna 27,587 K.P.S Kumarasiri 49,030 Sri Lanka Podujana Peramuna (SLPP) Rajitha Aluvihare 27,171 Wasantha Aluwihare 25,989 Samagi Jana Balawegaya (SJB) Dhaya Nandasiri 17,216 Ibrahim Mohammed Shifnas 13,518 Ishaq Rahman 49,290 Sarath Weerasekara Thissa Bandara Herath 9,224 Rohana Bandara Wijesundara 39,520 328,092 Maithiri Dosan 5,856 Suppaiya Yogaraj 4,900 Wimal Weerawansa 267, 084 DIGAMADULLA DISTRICT Udaya Gammanpila 136, 331 Sri Lanka Podujana Peramuna (SLPP) Wijeyadasa Rajapakshe 120, 626 PUTTALAM DISTRICT Bandula Gunawardena 101, 644 Pradeep Undugoda 91, 958 Sri Lanka Podujana Peramuna (SLPP) Wimalaweera Dissanayake 63,594 Samagi Jana Balawegaya (SJB) Sanath Nishantha Perera Sajith Premadasa 305, 744 80,082 S.M. Marikkar 96,916 D. Weerasinghe 56,006 Mujibur Rahman 87, 589 Thilak Rajapaksha 54,203 Harsha de Silva 82, 845 Piyankara Jayaratne 74,425 Patali Champika Ranawaka 65, 574 Arundika Fernando 70,892 Mano Ganesan 62, 091 Chinthaka Amal Mayadunne 46,058 Samagi Jana Balawegaya (SJB) Ashoka Priyantha 41,612 Mohomed Haris 36,850 Mohomed Faizal 29,423 BADULLA DISTRICT Samagi Jana Balawegaya (SJB) Sri Lanka Podujana Peramuna (SLPP) Hector Appuhamy 34,127 National Congress (NC) Niroshan Perera 31,636 Athaulla Ahamed 35,697 Nimal Siripala de Silva Muslim National Alliance (MNA) All Ceylon Makkal Congress (ACMC) 141, 901 Abdul Ali Sabry 33,509 Mohomed Mushraf -

Accommodating Minorities Into Sri Lanka's Post-Civil War State

E-ISSN 2281-4612 Academic Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies Vol 9 No 6 November 2020 ISSN 2281-3993 www.richtmann.org . Research Article © 2020 Fazil et.al.. This is an open access article licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) Accommodating Minorities into Sri Lanka’s Post-Civil War State System: Government Initiatives and Their Failure Mansoor Mohamed Fazil1* Mohamed Anifa Mohamed Fowsar1 Vimalasiri Kamalasiri1 Thaharadeen Fathima Sajeetha1 Mohamed Bazeer Safna Sakki1 1Department of Political Science, Faculty of Arts and Culture, South Eastern University of Sri Lanka, University Park, Oluvil, Sri Lanka *Corresponding Author DOI: https://doi.org/10.36941/ajis-2020-0132 Abstract Many observers view the defeat of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) in May 2009 as a significant turning point in the protracted ethnic conflict that was troubling Sri Lanka. The armed struggle and the consequences of war have encouraged the state and society to address the group rights of ethnic minorities and move forward towards state reconstitution. The Tamil minority and international community expect that the Government of Sri Lanka (GOSL) must introduce inclusive policies as a solution to the ethnic conflict. They believe the state should take measures to avoid another major contestation through the lessons learned from the civil war. The study is a qualitative analysis based on text analysis. In this backdrop, this paper examines the attempts made for the inclusion of minorities into the state system in post-civil war Sri Lanka, which would contribute to finding a resolution to the ethnic conflict. -

Minutes of Parliament Present

(Ninth Parliament - First Session) No. 59.] MINUTES OF PARLIAMENT Wednesday, March 10, 2021 at 10.00 a.m. PRESENT : Hon. Mahinda Yapa Abeywardana, Speaker Hon. Ranjith Siyambalapitiya, Deputy Speaker and the Chair of Committees Hon. Angajan Ramanathan, Deputy Chairperson of Committees Hon. Mahinda Rajapaksa, Prime Minister and Minister of Finance, Minister of Buddhasasana, Religious & Cultural Affairs and Minister of Urban Development & Housing Hon. Mahinda Amaraweera, Minister of Environment Hon. Mahindananda Aluthgamage, Minister of Agriculture Hon. Udaya Gammanpila, Minister of Energy Hon. Dinesh Gunawardena, Minister of Foreign and Leader of the House of Parliament Hon. (Dr.) Bandula Gunawardana, Minister of Trade Hon. S. M. Chandrasena, Minister of Lands Hon. Janaka Bandara Thennakoon, Minister of Public Services, Provincial Councils & Local Government Hon. Nimal Siripala de Silva, Minister of Labour Hon. (Prof.) G. L. Peiris, Minister of Education Hon. Johnston Fernando, Minister of Highways and Chief Government Whip Hon. Prasanna Ranatunga, Minister of Tourism Hon. Keheliya Rambukwella, Minister of Mass Media Hon. Chamal Rajapaksa, Minister of Irrigation and State Minister of National Security & Disaster Management and State Minister of Home Affairs Hon. Gamini Lokuge, Minister of Transport Hon. (Mrs.) Pavithradevi Wanniarachchi, Minister of Health Hon. (Dr.) Sarath Weerasekera, Minister of Public Security Hon. M .U. M. Ali Sabry, Minister of Justice Hon. (Dr.) (Mrs.) Seetha Arambepola, State Minister of Skills Development, Vocational Education, Research and Innovation ( 2 ) M. No. 59 Hon. Lasantha Alagiyawanna, State Minister of Co-operative Services, Marketing Development and Consumer Protection Hon. Ajith Nivard Cabraal, State Minister of Money & Capital Market and State Enterprise Reforms Hon. (Dr.) Nalaka Godahewa, State Minister of Urban Development, Coast Conservation, Waste Disposal and Community Cleanliness Hon. -

Minutes of Parliament for 23.01.2020

(Eighth Parliament - Fourth Session ) No . 7. ]]] MINUTES OF PARLIAMENT Thursday, January 23, 2020 at 10.30 a.m. PRESENT ::: Hon. J. M. Ananda Kumarasiri, Deputy Speaker and the Chair of Committees Hon. Mahinda Amaraweera, Minister of Transport Service Management and Minister of Power & Energy Hon. Dinesh Gunawardena, Minister of Foreign Relations and Minister of Skills Development, Employment and Labour Relations and Leader of the House of Parliament Hon. S. M. Chandrasena, Minister of Environment and Wildlife Resources and Minister of Lands & Land Development Hon. (Dr.) Ramesh Pathirana, Minister of Plantation Industries and Export Agriculture Hon. Johnston Fernando, Minister of Roads and Highways and Minister of Ports & Shipping and Chief Government Whip Hon. Prasanna Ranatunga, Minister of Industrial Export and Investment Promotion and Minister of Tourism and Civil Aviation Hon. Mahinda Yapa Abeywardena, State Minister of Irrigation and Rural Development Hon. Lasantha Alagiyawanna, State Minister of Public Management and Accounting Hon. Mahindananda Aluthgamage, State Minister of Power Hon. Duminda Dissanayake, State Minister of Youth Affairs Hon. S. B. Dissanayake, State Minister of Lands and Land Development Hon. Wimalaweera Dissanayaka, State Minister of Wildlife Resources Hon. Vasudeva Nanayakkara, State Minister of Water Supply Facilities Hon. Susantha Punchinilame, State Minister of Small & Medium Enterprise Development Hon. A. D. Susil Premajayantha, State Minister of International Co -operation Hon. Tharaka Balasuriya, State Minister of Social Security Hon. C. B. Rathnayake, State Minister of Railway Services Hon. Nimal Lanza, State Minister of Community Development ( 2 ) M. No. 7 Hon. Gamini Lokuge, State Minister of Urban Development Hon. Janaka Wakkumbura, State Minister of Export Agriculture Hon. Vidura Wickramanayaka, State Minister of Agriculture Hon. -

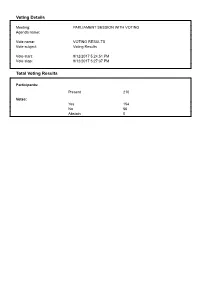

Voting Details Total Voting Results

Voting Details Meeting: PARLIAMENT SESSION WITH VOTING Agenda name: Vote name: VOTING RESULTS Vote subject: Voting Results Vote start: 9/12/2017 5:24:51 PM Vote stop: 9/12/2017 5:27:37 PM Total Voting Results Participants: Present 210 Votes: Yes 154 No 56 Abstain 0 Individual Voting Results GOVERNMENT SIDE G 001. Mangala Samaraweera Yes G 002. S.B. Dissanayake Yes G 003. Nimal Siripala de Silva Yes G 004. Gamini Jayawickrama Perera Yes G 005. John Amaratunga Yes G 006. Lakshman Kiriella Yes G 007. Ranil Wickremesinghe Yes G 009. Gayantha Karunatileka Yes G 010. W.D.J. Senewiratne Yes G 011. Sarath Amunugama Yes G 012. Rauff Hakeem Yes G 013. Rajitha Senaratne Yes G 014. Rishad Bathiudeen Yes G 015. Kabir Hashim Yes G 016. Sajith Premadasa Yes G 017. Malik Samarawickrama Yes G 018. Mano Ganesan Yes G 019. Anura Priyadharshana Yapa Yes G 020. Ven. Athuraliye Rathana Thero Yes G 021. Thilanga Sumathipala Yes G 022. A.D. Susil Premajayantha Yes G 023.Tilak Marapana Yes G 024. Mahinda Samarasinghe Yes G 025. Wajira Abeywardana Yes G 026. S.B. Nawinne Yes G 028. Patali Champika Ranawaka Yes G 029. Mahinda Amaraweera Yes G 030. Navin Dissanayake Yes G 031. Ranjith Siyambalapitiya Yes G 032. Duminda Dissanayake Yes G 033. Wijith Wijayamuni Zoysa Yes G 034. P. Harrison Yes G 035. R.M. Ranjith Madduma Bandara Yes G 036. Arjuna Ranatunga Yes G 037. Palany Thigambaram Yes G 038. Chandrani Bandara Yes G 039. Thalatha Atukorale Yes G 040. Akila Viraj Kariyawasam Yes G 041. -

[email protected] Hon. Prime Minister Ranil Wickramasinghe PM

Via email - [email protected] Hon. Prime Minister Ranil Wickramasinghe PM Office 58, Sir Earnest De Silva Mawatha, Colombo 07. Dear Sir, Demand for arrest of monks who resorted to violence against Rohingya refugees using hate speech We do not intend going into details of the violent and inhuman protest on 26 September (2017) led by Buddhist monks against Rohingya refugees who were sheltered in a 'safehouse' in Mt.Lavinia by the Colombo office of the UNHCR. An incident, we are certain you are well briefed about. This racially motivated violent incident brought international disrepute and proved the government is uncertain in stopping such hate mongering violent protests when led by Buddhist monks. Except for Ministers Mangala Samaraweera and Rajitha Senaratne who in their personal capacities, were very vocal in condemning the extremist Buddhist monks and their violent racist thuggery, followed by Minister Mano Ganesan, we are yet to see the government officially and with authority intervening in clearing doubts on the Rohingya refugee issue, the anti-Muslim extremist groups have been campaigning on distorted and warped information of their own creation. The belated statement made by the Secretary, Ministry for Law and Order on 28 September, is only a vague, face saving attempt. He says 03 investigating police teams have been deployed while the Acting IGP said investigations are handed over to the Colombo Crime Division (CCD). We are aware how 04 such teams were deployed to arrest the Bodu Bala Sena (BBS) leader Galagodaatte Gnanasara thero, while his lawyer submitted a medical certificate to Courts for his inability to be present. -

From: MANO GANESAN

From the office of Mano GANESAN Leader of Western People’s Front Convener of Civil Monitoring Commission President of Democratic Worker’s Congress Member of Parliament for Colombo District Fax +94112435961 Email: [email protected] Post Box 803 Colombo SRI LANKA . Essence of speech made by Mano Ganesan MP in Parliament during the debate of the extension of emergency on 06th May , 2008 (Thank you Mr. Deputy Speaker.) I was fortunate to listen to Jatika Hela Urumaya’s Ven. Metananda Thero. Hon Member of Parliament Ven. Thero spoke about the prevailing situation at Madu church in Mannar. He started by saying that Madu Church was once a Buddhist temple later became a Hindu temple. He claimed that the Portuguese demolished the Hindu temple and built this Madu church. Now the Bishop of Mannar Rev. Rayappu Joseph has called both the government and the LTTE to agree to the proposal of making the Madu church and environment to be declared as a peace zone. Ven. Thero is calling the Bishop wrong. We wish to very categorically state that Ven. Thero is making matters worse based on Buddhist fundamentalism. It is further making matters worse and amount to opening up a war front between the Buddhist and Catholics. I can explain. We have very often heard many frequent voices from the government benches , from the JHU , from the southern polity , from the international community calling upon the Tamil people to ‘advice’ the LTTE to change it’s course from violence to democracy. Yes , it is correct. The interests of the people should prevail over any organisation or government. -

Minutes of Parliament for 21.05.2019

(Eighth Parliament - Third Session ) No . 61 . ] MINUTES OF PARLIAMENT Tuesday, May 21, 2019 at 1.00 p. m. PRESENT ::: Hon. Karu Jayasuriya, Speaker Hon. J. M. Ananda Kumarasiri, Deputy Speaker and the Chair of Committees Hon. Selvam Adaikkalanathan, Deputy Chairperson of Committees Hon. Ranil Wickremesinghe, Prime Minister and Minister of National Policies, Economic Affairs, Resettlement & Rehabilitation, Northern Province Development and Youth Affairs Hon. (Mrs.) Thalatha Atukorale, Minister of Justice & Prison Reforms Hon. Wajira Abeywardana, Minister of Internal & Home Affairs and Provincial Councils & Local Government Hon. John Amaratunga, Minister of Tourism Development, Wildlife and Christian Religious Affairs Hon. Gayantha Karunatileka, Minister of Lands and Parliamentary Reforms and Chief Government Whip Hon. Ravi Karunanayake, Minister of Power, Energy and Business Development Hon. Akila Viraj Kariyawasam, Minister of Education Hon. Lakshman Kiriella, Minister of Public Enterprise, Kandyan Heritage and Kandy Development and Leader of the House of Parliament Hon. Mano Ganesan, Minister of National Integration, Official Languages, Social Progress and Hindu Religious Affairs Hon. Daya Gamage, Minister of Primary Industries and Social Empowerment Hon. Gamini Jayawickrama Perera, Minister of Buddhasasana & Wayamba Development Hon. Harin Fernando, Minister of Telecommunication, Foreign Employment and Sports Hon. Sajith Premadasa, Minister of Housing, Construction and Cultural Affairs Hon. (Mrs.) Chandrani Bandara, Minister of Women & Child Affairs and Dry Zone Development Hon. R. M. Ranjith Madduma Bandara, Minister of Public Administration & Disaster Management ( 2 ) M. No. 61 Hon. Rishad Bathiudeen, Minister of Industry & Commerce, Resettlement of Protracted Displaced Persons, Co -operative Development and Vocational Training & Skills Development Hon. Tilak Marapana, Minister of Foreign Affairs Hon. Sagala Ratnayaka, Minister of Ports & Shipping and Southern Development Hon. -

In the Supreme Court of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA In the matter of an application under and in terms of Articles 17 and 126 of the Constitution of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka Ranjith Madduma Bandara, 31/3 Kandawatte Terrace, Nugegoda PETITIONER SC FR Application No.-: _____ /2020 -VS- 1. (a) Attorney General, Attorney General’s Department, Hulftsdorp, Colombo 12. 1. (b) Attorney General, Attorney General’s Department, Hulftsdorp, Colombo 12. 2. Mahinda Deshapriya, Chairman 3. N. J. Abeysekera, Member 4. Ratnajeevan Hoole, Member 2nd – 4th Respondents all of, Election Commission, Sarana Mawatha, Rajagiriya RESPONDENTS On this 5th day of May 2020 Page 1 of 31 TO: HIS LORDSHIP THE CHIEF JUSTICE AND THEIR LORDSHIPS THE OTHER HONOURABLE JUDGES OF THE SUPREME COURT OF THE DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA The Petition of the Petitioner above named appearing by Dinesh Vidanapathirana his registered Attorney-at-Law, states as follows; THE PETITIONER 1. The Petitioner is: (a) a citizen of Sri Lanka, (b) a Member of the Eighth Parliament of Sri Lanka, and (c) the General Secretary of the Samagi Jana Balawegaya, a Registered Political Party, which tendered Nomination Forms for all 22 Districts of Sri Lanka, for the Parliamentary Elections 2020. 2. The Petitioner makes this Application in his own right and in the public interest, with the objective of safeguarding the rights and interests of the general public of Sri Lanka and securing due respect, regard for and adherence to the Rule of Law, the Constitution, which is the supreme law of the land, and with a view to protecting the fundamental rights required to be respected, secured and advanced as morefully set out, hereinafter.