The Hammer Bottom Hike Supporting Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Godalming Band Newsletter November, 2015

GODALMING BAND NEWSLETTER NOVEMBER, 2015 Dear Readers, I hope you enjoy this issue of the Newsletter about the Bands’ activities. The Youth Band has had an especially active year, as seen below. You will find here information about engagements, achievements, and a comprehensive report on the Senior Band’s recent trip to Joigny, as presented by Dominic Cleal. David Daniels, Editor CHAIRMAN’S MESSAGE Welcome to our Autumn Newsletter. 2015 has been a very busy and different year, especially for the Senior Band. Much of the early part of the year was spent preparing for the regional qualifying contest of the national brass band championships in March and for the Mayor of Waverley’s massed bands charity concert at Charterhouse in April. In addition to our usual summer events including an outdoor concert at King Edward’s School, Witley, much of our time and effort went into preparing for the Senior Band’s visit to Joigny, France in October. This visit was at the invitation of the ‘Harmonie de Joigny’, the wind band of the music academy in our French twin town, to celebrate their 150th anniversary. Now as the festive season approaches our Bands are busy preparing for the numerous local engagements as well as the joint annual Christmas Concert on Saturday 19th December, 2015. Thank you for your continued interest and support. We hope to see you and your friends and family at the United Church in Godalming on the 19th. Ray Pont, Band Chairman 1 A WORD FROM DAVID LOFTUS, YOUTH BAND MD As I write for this newsletter we are rapidly heading towards another very busy Christmas set of engagements. -

THE SERPENT TRAIL11.3Km 7 Miles 1 OFFICIAL GUIDE

SOUTH DOWNS WALKS ST THE SERPENT TRAIL11.3km 7 miles 1 OFFICIAL GUIDE ! HELPFUL HINT NATIONAL PARK The A286 Bell Road is a busy crossing point on the Trail. The A286 Bell Road is a busy crossing point on the Trail. West of Bell Road (A286) take the path that goes up between the houses, then across Marley Hanger and again up between two houses on a tarmac path with hand rail. 1 THE SERPENT TRAIL HOW TO GET THERE From rolling hills to bustling market towns, The name of the Trail reflects the serpentine ON FOOT BY RAIL the South Downs National Park’s (SDNP) shape of the route. Starting with the serpent’s The Greensand Way (running from Ham The train stations of Haslemere, Liss, 2 ‘tongue’ in Haslemere High Street, Surrey; landscapes cover 1,600km of breathtaking Street in Kent to Haslemere in Surrey) Liphook and Petersfield are all close to the views, hidden gems and quintessentially the route leads to the ‘head’ at Black Down, West Sussex and from there the ‘body’ finishes on the opposite side of Haslemere Trail. Visit nationalrail.co.uk to plan English scenery. A rich tapestry of turns west, east and west again along High Street from the start of the Serpent your journey. wildlife, landscapes, tranquillity and visitor the greensand ridges. The trail ‘snakes’ Trail. The Hangers Way (running from attractions, weave together a story of Alton to the Queen Elizabeth Country Park by Liphook, Milland, Fernhurst, Petworth, BY BUS people and place in harmony. in Hampshire) crosses Heath Road Fittleworth, Duncton, Heyshott, Midhurst, Bus services run to Midhurst, Stedham, in Petersfield just along the road from Stedham and Nyewood to finally reach the Trotton, Nyewood, Rogate, Petersfield, Embodying the everyday meeting of history the end of the Serpent Trail on Petersfield serpent’s ‘tail’ at Petersfield in Hampshire. -

Frensham Parish Council

Frensham Parish Council Village Design Statement Contents 1. What is a VDS? 2. Introduction & History 3. Open Spaces & Landscape 4. Buildings – Style & Detail 5. Highways & Byways 6. Sports & rural Pursuits Summary Guidelines & Action Points Double page spread of parish map in the centre of document Appendix: Listed Buildings & Artefacts in Parish 1 What is a Village Design Statement? A Village Design Statement (VDS) highlights the qualities, style, building materials, characteristics and landscape setting of a parish, which are valued by its residents. The background, advice and guidelines given herein should be taken into account by developers, builders and residents before considering development. The development policies for the Frensham Parish area are the “saved Policies” derived from Waverley Borough Council’s Local Plan 2002, (which has now been superseded. It is proposed that the Frensham VDS should be Supplementary Planning Guidance, related to Saved Policy D4 ‘Design and Layout’. Over recent years the Parish Council Planning Committee, seeing very many applications relating to our special area, came to the conclusion that our area has individual and special aspirations that we wish to see incorporated into the planning system. Hopefully this will make the Parish’s aspirations clearer to those submitting applications to the Borough Council and give clear policy guidance. This document cannot be exhaustive but we hope that we have included sufficient detail to indicate what we would like to conserve in our village, and how we would like to see it develop. This VDS is a ‘snapshot’ reflecting the Parish’s views and situation in2008, and may need to be reviewed in the future in line with changing local needs, and new Waverley, regional and national plans and policies. -

Download Brochure

WELCOME to BROADOAKS PAR K — Inspirational homes for An exclusive development of luxurious Built by Ernest Seth-Smith, the striking aspirational lifestyles homes by award winning housebuilders Broadoaks Manor will create the Octagon Developments, Broadoaks Park centrepiece of Broadoaks Park. offers the best of countryside living in Descending from a long-distinguished the heart of West Byfleet, coupled with line of Scottish architects responsible for excellent connections into London. building large areas of Belgravia, from Spread across 25 acres, the gated parkland Eaton Square to Wilton Crescent, Seth-Smith estate offers a mixture of stunning homes designed the mansion and grounds as the ranging from new build 2 bedroom ultimate country retreat. The surrounding apartments and 3 - 6 bedroom houses, lodges and summer houses were added to beautifully restored and converted later over the following 40 years, adding apartments and a mansion house. further gravitas and character to the site. Surrey LIVING at its BEST — Painshill Park, Cobham 18th-century landscaped garden with follies, grottoes, waterwheel and vineyard, plus tearoom. Experience the best of Surrey living at Providing all the necessities, a Waitrose Retail therapy Broadoaks Park, with an excellent range of is located in the village centre, and Guildford’s cobbled High Street is brimming with department stores restaurants, parks and shopping experiences for a wider selection of shops, Woking and and independent boutiques alike, on your doorstep. Guildford town centres are a short drive away. offering one of the best shopping experiences in Surrey. Home to artisan bakeries, fine dining restaurants Opportunities to explore the outdoors are and cosy pubs, West Byfleet offers plenty plentiful, with the idyllic waterways of the of dining with options for all occasions. -

Sailor's Stone and Gibbet Hill Walk

Following in the Sailor’s footsteps Hindhead and Haslemere Area The Hindhead and Haslemere area became popular with authors and th THE HASLEMERE INITIATIVE In order to imagine walking along this path at the time of our artists in the late 19 century, when the railway opened up this part of ‘unknown sailor’, one must block out the sound of the modern A3 Surrey. Haslemere is an attractive old market town nestling near the road and replace it with that of more leisurely transport. Although point where three counties meet. It was described in an early visitor the A3 between Kingston and Petersfield had become a turnpike guide as the ‘fashionable capital of the beautiful Surrey highlands’ in 1758, many people still travelled by foot. The distant conversa- and now lies within the Surrey Hills Area of Outstanding Natural SAILOR’S STONE tions of these travellers would have been accompanied only by the Beauty (AONB). Much of the lovely countryside around this area is occasional trundle of a horse drawn coach, the clopping of hooves now owned by The National Trust. or the bleat of a sheep. Walkers familiar with the exploits of Hindhead Common AND Nicholas Nickleby for example might recall his journey with Smike. Hindhead Common, with over 566ha of heath and woodland, was one Whilst on the way to Godalming the two characters are found on of the first countryside areas acquired by The National Trust and is an the very path you walk now on their way to the memorial at Gibbet exceptional site for heathland restoration. -

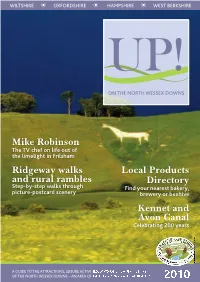

Local Products Directory Kennet and Avon Canal Mike Robinson

WILTSHIRE OXFORDSHIRE HAMPSHIRE WEST BERKSHIRE UP! ON THE NORTH WESSEX DOWNS Mike Robinson The TV chef on life out of the limelight in Frilsham Ridgeway walks Local Products and rural rambles Directory Step-by-step walks through Find your nearest bakery, picture-postcard scenery brewery or beehive Kennet and Avon Canal Celebrating 200 years A GUIDE TO THE ATTRACTIONS, LEISURE ACTIVITIES, WAYS OF LIFE AND HISTORY OF THE NORTH WESSEX DOWNS – AN AREA OF OUTSTANDING NATURAL BEAUTY 2010 For Wining and Dining, indoors or out The Furze Bush Inn provides TheThe FurzeFurze BushBush formal and informal dining come rain or shine. Ball Hill, Near Newbury Welcome Just 2 miles from Wayfarer’s Walk in the elcome to one of the most beautiful, amazing and varied parts of England. The North Wessex village of Ball Hill, The Furze Bush Inn is one Front cover image: Downs was designated an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB) in 1972, which means of Newbury’s longest established ‘Food Pubs’ White Horse, Cherhill. Wit deserves the same protection by law as National Parks like the Lake District. It’s the job of serving Traditional English Bar Meals and an my team and our partners to work with everyone we can to defend, protect and enrich its natural beauty. excellent ‘A La Carte’ menu every lunchtime Part of the attraction of this place is the sheer variety – chances are that even if you’re local there are from Noon until 2.30pm, from 6pm until still discoveries to be made. Exhilarating chalk downs, rolling expanses of wheat and barley under huge 9.30pm in the evening and all day at skies, sparkling chalk streams, quiet river valleys, heaths, commons, pretty villages and historic market weekends and bank holidays towns, ancient forest and more.. -

The Ultra Participant Information Pack

www.surreyhillschallenge.co.uk THE ULTRA PARTICIPANT INFORMATION PACK 23/09/2018 INTRODUCTION www.surreyhillschallenge.co.uk Welcome We are delighted to welcome you to the Surrey Hills Challenge on Sunday 23rd September 2018. You have entered the Ultra, our 60km off road running challenge. The point to point route is from Haslemere to Dorking along the Greensand Way with a 12 hour cut off period. The postcode to find the start is GU27 2AS, and there will be yellow directional signage to help you find us. Parking is free on Sundays and there are a number of car parks to choose from. In the main centre of Haslemere, you can park at the High Street pay and display car park or at the Chestnut Avenue pay and display car park (better for longer periods). If you want to park close to the train station, or park for a long period of time during the day, Tanners Lane and Weydown Road pay and display car parks are close to the station. Itinerary Time Activity 05:30 Doors open at Haslemere Hall, Bridge Rd, Haslemere GU27 2AS 2AS 06:00 Registration opens • Runner registration and bib collection • Finish Line Bag deposit open 06:40 Race brief 06:50 100m walk to start line 07:00 Start of Ultra 19:00 Cut off and race finish at Denbies Wine Estate (London Road, Dorking RH5 6AA) Route Conditions The route mainly follows the Greensand Way, which originates in Haslemere and continues east to Kent. It’s marked with official ‘GW’ and ‘Greensand Way’ signs and will also be marked up by our team with approximately 200 directional fluorescent signs. -

Haslemere-To-Guildford Monster Distance: 33 Km=21 Miles Moderate but Long Walking Region: Surrey Date Written: 15-Mar-2018 Author: Schwebefuss & Co

point your feet on a new path Haslemere-to-Guildford Monster Distance: 33 km=21 miles moderate but long walking Region: Surrey Date written: 15-mar-2018 Author: Schwebefuss & Co. Last update: 14-oct-2020 Refreshments: Haslemere, Hindhead, Tilford, Puttenham, Guildford Maps: Explorer 133 (Haslemere) & 145 (Guildford) Problems, changes? We depend on your feedback: [email protected] Public rights are restricted to printing, copying or distributing this document exactly as seen here, complete and without any cutting or editing. See Principles on main webpage. Heath, moorland, hills, high views, woodland, birch scrub, lakes, river, villages, country towns In Brief This is a monster linear walk from Haslemere to Guildford. It combines five other walks in this series with some short bridging sections. You need to browse, print or download the following additional walks: Hindhead and Blackdown Devil’s Punch Bowl, Lion’s Mouth, Thursley Puttenham Common, Waverley Abbey & Tilford Puttenham and the Welcome Woods Guildford, River Wey, Puttenham, Pilgrims Way Warning! This is a long walk and should not be attempted unless you are physically fit and have back-up support. Boots and covered legs are recommended because of the length of this walk. A walking pole is also recommended. This monster walk is not suitable for a dog. There are no nettles or briars to speak of. The walk begins at Haslemere Railway Station , Surrey, and ends at Guildford Railway Station. Trains run regularly between Haslemere and Guildford and both are on the line from London Waterloo with frequent connections. For details of access by road, see the individual guides. -

"Doubleclick Insert Picture"

Hindhead Guide Price £475,000 Hindhead Guide Price £475,000 17 Hunters Place, Hindhead, GU26 6UY Set in a gated development, a fine three storey town house offering stylish family accommodation within the heart of Hindhead just a few hundred yards from all that Hindhead Commons and the Devil's Punchbowl has to offer, yet a little over a mile to Grayshott Village, the A3 and about three miles to Haslemere Main Line Station (Waterloo in under the hour). • Contemporary stylish living The rear garden is enclosed by panel fencing and laid principally to lawn with the • Close to National Trust Commons afore mentioned terrace overlooking it. Within the development is an enclosed • Gated development communal childrens play area. • Accommodation over three floors • Main bedroom suite ESTATE SERVICE CHARGE • Three further double bedrooms Currently £440.24 pa to cover ground maintenance, electric gates and such like. Open plan ground floor INTERNET CONNECTIVITY: Two car spaces High speed is available within the area Garden & communal children play area Remainder of the NHBC Guarantee LOCAL AUTHORITY Waverley Borough Council Tax Band: E Hindhead is the highest Village in Surrey, best known as the location of the Devils Punch Bowl, a stunning TENURE local beauty spot and a site of scientific interest, notorious in the 18th Century for highwaymen. Freehold In 1786 three men were convicted of the murder of an unknown sailor making his way from London to his ship, and the perpetrators were hung in chains as a warning to others on the EPC RATING: B nearby 'Gibbet Hill', just a short walk from the Punchbowl. -

Fifty Years of Surrey Championship Cricket

Fifty Years of Surrey Championship Cricket History, Memories, Facts and Figures • How it all started • How the League has grown • A League Chairman’s season • How it might look in 2043? • Top performances across fifty years HAVE YOUR EVENT AT THE KIA OVAL 0207 820 5670 SE11 5SS [email protected] events.kiaoval.com Surrey Championship History 1968 - 2018 1968 2018 Fifty Years of Surrey 1968 2018 Championship Cricket ANNIVERSA ANNIVERSA 50TH RY 50TH RY April 2018 PRESIDENT Roland Walton Surrey Championship 50th Anniversary 1968 - 2018 Contents Diary of anniversary activities anD special events . 4 foreworD by peter Murphy (chairMan) . 5 the surrey chaMpionship – Micky stewart . 6 Message froM richarD thoMpson . 7 the beginning - MeMories . 9. presiDent of surrey chaMpionship . 10 reflections anD observations on the 1968 season . 16 sccca - final 1968 tables . 19 the first Match - saturDay May 4th 1968 . 20 ten years of league cricket (1968 - 1977) . 21 the first twenty years - soMe personal MeMories . 24 Message froM Martin bicknell . 27 the history of the surrey chaMpionship 1968 to 1989 . 28 the uMpires panel . 31 the seconD 25 years . 32 restructuring anD the preMier league 1994 - 2005 . 36 the evolution of the surrey chaMpionship . 38 toDay’s ecb perspective of league cricket . 39 norManDy - froM grass roots to the top . 40 Diary of a league chairMan’s season . 43 surrey chaMpionship coMpetition . 46 expansion anD where are they now? . 47 olD grounDs …..….. anD new! . 51 sponsors of the surrey chaMpionship . 55 what Might the league be like in 25 years? . 56 surrey chaMpionship cappeD surrey players . 58 history . -

Brook Farm House Brook, Godalming, Surrey

Brook Farm House Brook, Godalming, Surrey Brook Farm House Brook, Godalming, Surrey Haslemere 4 miles (London Waterloo from 55 minutes), Godalming 5.3 miles, Guildford 9 miles, London 40 miles (All mileages and time are approximate) A beautifully presented former dairy in the heart of one of the best villages in surrey enjoying views over the adjoining Witley Park Estate. Accommodation Double height reception hall | Drawing room | Dining room | Study/family room Kitchen/breakfast room | Utility room | Cloakroom Master bedroom with en suite bathroom 4 Further bedrooms | 2 Further bath/shower rooms (1 en suite) | Eaves storage Double open bay garage with store above Wonderful gardens with terracing, lawns and a wisteria walk In all about 0.86 acres Knight Frank Guildford 2-3 Eastgate Court, High Street, Guildford, Surrey GU1 3DE Tel: +44 1483 617 910 [email protected] knightfrank.co.uk The Location Set in the heart of the village with its attractive cricket ground, village hall and quintessential country pub, Dog and Pheasant, Brook Farm House is ideally located to the north of Haslemere which is a thriving small town with a Waitrose and numerous excellent shops and recreational facilities. The station offers a frequent train service to London Waterloo which takes from 55 minutes whilst there are other stations further up the line including Witley and Farncombe. The countryside surrounding the village is some of the finest in the county and offers many miles of footpaths and bridleways. The A3 can be accessed to the north at Milford providing easy access to the M25, London and both airports. -

Thursley Welcome Pack

Thursley Welcome Pack Thursley Welcome Pack 1.0 Introduction Welcome to our parish! This document is intended to provide you with a brief introduction to the history and the facilities available in our parish. 2.0 Thursley Parish Thursley has a comparatively small population (approx. 600) resident in one of the larger parishes (8 sq. miles) of the 21 in the Borough of Waverley, South West Surrey. The parish runs south from its border with Elstead Parish to the southern edge of the Devil’s Punch Bowl near Hindhead. Many years ago, the parish boundaries of Thursley extended as far as Haslemere, but now they are curtailed. They run around Thursley Common, including Warren Mere, and cut across to Bowlhead Green almost to Brook, then back past Boundless Farm to the Devil’s Punch Bowl. They then continue round the bowl to Pitch Place, down to Truxford and back on to the common again. Thursley Welcome Pack Thursley has a cricket green, a large recreation ground which allows parking and a play area upgraded in 2015 as a result of community funding. It attracts many visitors who come to see the village and the local commons via the extensive footpath and bridleway network. The Greensand Way runs through the parish. Bowlhead Green also has an attractive green, and is more agricultural in character than Thursley. Pitch Place has Hankley Common to the north, the orchards and fruit farms to the south and tracks that lead to Hindhead Common and beyond. In popular myth the name Thursley is of Scandinavian origin, meaning the “sacred grove of Thor”, the Norse god of thunder.