Unacceptable Harm

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Failure of UN Security Council Resolution 2286 in Preventing Attacks on Healthcare in Syria

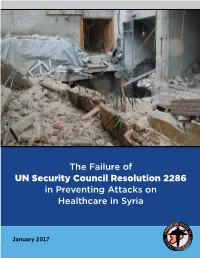

The Failure of UN Security Council Resolution 2286 in Preventing Attacks on Healthcare in Syria January 2017 SYRIAN AMERICAN MEDICAL SOCIETY C1 Contents Acknowledgements C3 Foreword 1 Background 2 Methodology 2 Executive Summary 3 Attacks on Healthcare, June–December 2016 4 Advanced and Unconventional Weaponry 7 All Forms of Medical Facilities and Personnel Targeted 7 Conclusion 8 Appendix: Attacks on Medical Personnel, June–December 2016 9 ABOUT THE SYRIAN AMERICAN MEDICAL SOCIETY The Syrian American Medical Society (SAMS) is a non-profit, non-political, professional and medical relief organization that provides humanitarian assistance to Syrians in need and represents thousands of Syrian American medical professionals in the United States. Founded in 1998 as a professional society, SAMS has evolved to meet the growing needs and challenges of the medical crisis in Syria. Today, SAMS works on the front lines of crisis relief in Syria and neighboring countries to serve the medical needs of millions of Syrians, support doctors and medical professionals, and rebuild healthcare. From establishing field hospitals and training Syrian physicians to advocating at the highest levels of government, SAMS is working to alleviate suffering and save lives. On the cover: Aftermath of an attack on a hospital in Aleppo, October 2016 Design: Sensical Design & Communication C2 The Failure of UN Security Council Resolution 2286 in Preventing Attacks on Healthcare in Syria Acknowledgements None of our work would be made possible without Syria’s doctors, nurses, medical assistants, ambulance drivers, hospital staff, and humanitarian workers. Their inspiring work amidst the most dire of circumstances con- tinues to inspire us to help amplify their voices. -

Victims Assistance Factsheet

FACTSHEETS How to implement victim assistance obligations? UNDER THE MINE BAN TREATY OR THE CONVENTION ON CLUSTER MUNITIONS Concrete actions to improve the quality of life of victims and persons with disabilities VICTIM ASSISTANCE FACTSHEETS INTRODUCTION Assistance to victims of mine/explosive remnants of war (ERW) is an obligation for States Parties to the Mine Ban Treaty (MBT) and the Convention on Cluster Munitions (CCM). The Cartagena Action Plan and the Vientiane Action Plan include specific commitments that States Parties have agreed on to implement their victim assistance (VA) obligations effectively, in particular to improve the quality of life of victims. The United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) provides the most comprehensive framework to address the needs & advances the rights of all persons with disabilities (PwD), including mine/ERW survivors. Regional frameworks on disability and development are also relevant, such as the Incheon Strategy to “Make the Right Real” for Persons with Disability in Asia and the Pacificand the African Decade of Persons with Disabilities. OBJECTIVE OF THESE FACTSHEETS The Victim Assistance Factsheets were developed by Handicap International (HI) as a tool to provide concise information on what victim assistance (VA) is and on how to translate it into concrete actions that have the potential to improve the quality of life of mine/ERW victims and persons with disabilities. The factsheets target States Parties affected by mine/ERW, States Parties in a position to provide assistance, as well as organizations of survivors and other PwD, and other civil society - and international organizations. METHODOLOGY The factsheets build on a review of existing literature on VA, Disability and Inclusive Development, including publications such as the WHO Community-Based Rehabilitation Guidelines, sector and country-specific publications by HI, as well as others by the Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention Implementation Support Unit, the ICRC and other organizations. -

Convention on the Prohibition of the Use, Stockpiling, Production and Transfer of Anti-Personnel Mines and on Their Destruction

The Convention on the Prohibition of the Use, Stockpiling, Production and Transfer of Anti-Personnel Mines and on their Destruction (Also known as the Ottawa Treaty, the Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention and the Mine Ban Treaty) Canada’s ratification of the treaty through domestic legislation was registered upon signature, 3 December 1997. Adoption: The Convention on the Prohibition of the Use, Stockpiling, Production and Transfer of Anti-Personnel Mines and on their Destruction was first open for signature on 3 December 1997. The treaty came into effect on March 1, 1999, six months after forty ratifications were confirmed. Entry into force: 1 March 1999. Number of signatories and ratifications/accessions: As of June 2016, there are 164 State Parties to the Convention, (32 states have not signed and remain outside the treaty, one state (the Marshall Islands) has signed but not ratified. The ratification option closed on 1 March 1999 for states that did not sign by that date. States can still accede to (join) the Treaty. Summary Information The purpose of the convention is to eliminate the humanitarian impact of antipersonnel mines through prohibition of their use, possession, transfer and production. The treaty also obliges signatories to remove mines from the ground and to destroy stockpiles. History An international civil society campaign organized by the International Campaign to Ban Landmines (ICBL) was established in 1992 to advance progress towards a treaty banning landmines. While at first the ICBL was comprised of a handful of non- governmental organizations, it quickly grew to a campaign of more than two thousand groups from around the world. -

Landmine Monitor 2014

Landmine Monitor 2014 Monitoring and Research Committee, ICBL-CMC Governance Board Handicap International Human Rights Watch Mines Action Canada Norwegian People’s Aid Research team leaders ICBL-CMC staff experts I © December 2014 by International Campaign to Ban Landmines – Cluster Munition Coalition (ICBL-CMC). All rights reserved. ISBN: 978-2-8399-1160-3 Cover photograph © Jared Bloch/ICBL-CMC, June 2014 Back cover © Werner Anderson/Norwegian People’s Aid, November 2013 Cover design by Rafael Jiménez Landmine and Cluster Munition Monitor provides research and monitoring for the Cluster Munition Coalition (CMC) and the International Campaign to Ban Landmines (ICBL). For more information visit www.the-monitor.org or email [email protected]. Landmine and Cluster Munition Monitor makes every effort to limit the environmental footprint of reports by pub- lishing all our research reports online. This report is available online at www.the-monitor.org. International Campaign to Ban Landmines The International Campaign to Ban Landmines (ICBL) is committed to the 1997 Mine Ban Treaty (or “Ottawa Conven- tion”) as the best framework for ending the use, production, stockpiling, and transfer of antipersonnel mines and for destroying stockpiles, clearing mined areas, and assisting affected communities. The ICBL calls for universal adherence to the Mine Ban Treaty and its full implementation by all, including: • No more use, production, transfer, and stockpiling of antipersonnel landmines by any actor under any circumstances; • Rapid destruction of all remaining stockpiles of antipersonnel landmines; • More efficient clearance and destruction of all emplaced landmines and explosive remnants of war (ERW); and • Fulfillment of the rights and needs of all landmine and ERW victims. -

United States / Afghanistan

December 2002 Vol. 14, No. 7 (G) UNITED STATES / AFGHANISTAN FATALLY FLAWED: CLUSTER BOMBS AND THEIR USE BY THE UNITED STATES IN AFGHANISTAN Acronyms Used In Report........................................................................................................................................ iii I. SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS.........................................................................................................1 Methodology ..........................................................................................................................................................3 Outline of Report....................................................................................................................................................3 Recommendations ..................................................................................................................................................4 To minimize the humanitarian harm of cluster bombs during strikes ................................................................4 To minimize the aftereffects of cluster bombs ...................................................................................................4 To improve clearance .........................................................................................................................................4 To develop better cluster bomb controls for the future ......................................................................................5 II. WHAT ARE CLUSTER BOMBS?.......................................................................................................................6 -

Cluster Weapons – Military Utility and Alternatives

FFI-rapport/2007/02345 Cluster weapons – military utility and alternatives Ove Dullum Forsvarets forskningsinstitutt/Norwegian Defence Research Establishment (FFI) 1 February 2008 FFI-rapport 2007/02345 Oppdrag 351301 ISBN 978-82-464-1318-1 Keywords Militære operasjoner / Military operations Artilleri / Artillery Flybomber / Aircraft bombs Klasevåpen / Cluster weapons Ammunisjon / Ammunition Approved by Ove Dullum Project manager Jan Ivar Botnan Director of Research Jan Ivar Botnan Director 2 FFI-rapport/2007/02345 English summary This report is made through the sponsorship of the Royal Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Its purpose is to get an overview of the military utility of cluster munitions, and to find to which degree their capacity can be substituted by current conventional weapons or weapons that are on the verge of becoming available. Cluster munition roughly serve three purposes; firstly to defeat soft targets, i e personnel; secondly to defeat armoured of light armoured vehicles; and thirdly to contribute to the suppressive effect, i e to avoid enemy forces to use their weapons without inflicting too much damage upon them. The report seeks to quantify the effect of such munitions and to compare this effect with that of conventional weapons and more modern weapons. The report discusses in some detail how such weapons work and which effect they have against different targets. The fragment effect is the most important one. Other effects are the armour piercing effect, the blast effect, and the incendiary effect. Quantitative descriptions of such effects are usually only found in classified literature. However, this report is exclusively based on unclassified sources. The availability of such sources has been sufficient to get an adequate picture of the effect of such weapons. -

1997 Convention on the Prohibition of Anti-Personnel Mines and on Their Destruction

ADVISORY SERVICE ON INTERNATIONAL HUMANITARIAN LAW ____________________________________ 1997 Convention on the Prohibition of Anti-Personnel Mines and on their Destruction The Convention on the Prohibition of the Use, Stockpiling, Production and Transfer of Anti-personnel Mines and on their Destruction ("the Ottawa treaty") is part of the international response to the widespread suffering caused by anti-personnel mines. The Convention is based on customary rules of international humanitarian law applicable. to all States. These rules prohibit the use of weapons which by their very nature do not discriminate between civilians and combatants or which cause unnecessary suffering or superfluous injury. The Convention was opened for signature in Ottawa on 3 December 1997 and entered into force on 1 March 1999. Why a ban on anti-personnel Which mines are affected by this the entry into force. Pending such mines? treaty? destruction, every effort must be made to identify mined areas and to Anti-personnel mines cannot Anti-personnel mines are designed have them marked, monitored and distinguish between soldiers and to be placed on or near the ground protected by fencing or other means civilians and usually kill or severely and to be "detonated by the to ensure the exclusion of civilians. mutilate their victims. Relatively presence, proximity or contact of a If a State cannot complete the cheap, small and easy to use, they person". It was the understanding of destruction of emplaced mines have proliferated by the tens of the negotiators that "improvised" within 10 years it may request a millions, inflicting untold suffering devices produced by adapting other meeting of the States Parties to and wreaking social and economic munitions to function as anti- extend the deadline and to assist it havoc in dozens of countries personnel mines were also banned in fulfilling this obligation. -

Game of Thrones? – Davos, the Download

Game of Thrones? – Davos, the download Mark Campanale, Tribe Impact Capital Fellow and Founder of the Carbon Tracker Initiative, reports back on his personal take from this year’s Davos. On arriving, you quickly come to understand that the World Economic Forum in Davos isn’t one event, but a series. Focused around the ‘official’ conference, global heads of corporations and governments gather: this is what we see covered on CNN or the BBC news networks. Outside this zone, a much larger muddle of NGO, policymakers and com- mentators gather, fighting for attention of both media and attendees. This parallel Davos is less well known, but is as jam-packed. And this is where I spent my week. The key to making Davos work for you is to learn how to navigate the complex network of parallel events, receptions and dinners. As there is no ‘programme’ to skim through, so working out where to be – and with whom - requires a good network. If fortune shines on you, attending events with just a ‘hotel pass’ (rather than the official ’basic’ at- tendance pass that can cost $50,000) can be and is often thoroughly rewarding. The schedule I created was focused on sustainability, financing the SDGs, climate change, sustainable food systems and yes - inevitably – what block chain will do to turn the world of business and finance on its head. If you like hopping between bars and hotel lobbies and dropping informally into wide ranging but thoughtful discus- sions (often with well-known public figures) then Davos is worth the hassle. -

Mark Malloch Brown Doctor of Laws

Mark Malloch Brown Doctor Of Laws Mark Malloch Brown, as a journalist, political adviser, and World Bank official, you have worked with politicians and executives from across the globe to address the needs of people in developing countries. As administrator of the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) since 1999, you have reformed the UN’s largest agency, raising more than $3 billion a year for programs to promote democracy, fight poverty, protect the environment, and address the impact of HIV/AIDS. Now as UN chief of staff you are helping the secretary- general lead a wide reform effort to modernize the UN. A British citizen, you received an honors degree in history from Cambridge University, and came to the United States to earn a master’s degree in political science from the University of Michigan. In 1977, you began work as a political correspondent for The Economist. You went on to found and edit the Economist Development Report, a monthly chronicle on the aid community and the political economy for development. From 1986 to 1994, you were lead international partner for the Sawyer-Miller Group, a consulting firm, where you advised corporations, governments, and political candidates. In this role, you worked on many campaigns across the developing world, including successfully advising Corazon Aquino when she ran against Ferdinand Marcos for the president of the Philippines. You began working for the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) in 1979. Initially stationed in Thailand, you were in charge of field operations for Cambodian refugees. Later, as deputy chief of the emergency unit in Geneva, you undertook missions in the Horn of Africa and Central America. -

Bower Entrapping Gulliver SS Final No Copyedits

Bower, Adam. 2020. “Entrapping Gulliver: The United States and the Antipersonnel Mine Ban.” Security Studies 29 (1): forthcoming. Accepted for publication 15 August 2019 In 2014, the Obama administration announced that the United States would almost entirely adopt the global ban on antipersonnel mines, despite longstanding military and political opposition. To explain this puzzling outcome, I expand upon recent accounts of rhetorical entrapment in which norm-promoting actors seek to compel change in a target actor by exploiting tensions between the target’s words and actions. Tracing US policy change over the past 25 years, I show how transnational civil society and domestic political elites strategically deployed factual and normative claims to draw US officials into an iterative debate concerning the humanitarian harm of antipersonnel mines. Successive US administrations have sought to mitigate external critique by gradually conceding to the discursive framing of pro-ban advocates without endorsing the international treaty prohibiting the weapons. These rhetorical shifts stimulated a search for alternative technologies and incremental changes to military doctrine, tactics, and procurement that constrained US policy choices culminating in the effective abandonment of antipersonnel mines despite ongoing military operations around the globe. In 2014, the United States announced that it would eliminate antipersonnel (AP) landmines from its military arsenal, with the exception of its ongoing security commitments on the Korean Peninsula.1 President Obama further committed “to continue to work to find ways that would allow us to ultimately comply fully and accede to the Ottawa Convention,” the 1997 international legal instrument eliminating the weapons also known as the Mine Ban Treaty (MBT).2 With these acts, the administration sought to reverse long-standing US opposition to the global landmine prohibition. -

UK Border Agency

UK Border Agency Title Instructions on drafting replies to MPs’ Correspondence Process Drafting of letters to enquiries from MPs’ and their offices 26 30 November Implementation Date November Expiry/Review Date 2009 2008 CONTAINS MANDATORY INSTRUCTIONS For Action Author All Ministerial drafting units within the UK Border Agency For Information Owner To all units in the UK Border Agency Jill Beckingham handling correspondence. Contact Point Processes Affected All processes relating to answering correspondence from Members of Parliament Assumptions Drafters have sufficient knowledge of their subject to accurately answer the questions raised by a Member of Parliament. NOTES 26 November Issued 2008 Version 3.1 Chapter 1 – General Advice on Correspondence Basics of Writing a Letter Letter Structure Addressing the Letter Opening Paragraph Middle Paragraphs Sign-off Enclosures Background Notes Parliamentary Conventions More than one MP has written about the same person Interim replies Requests from MPs for meetings Chapter 2 – Advice on Ministerial Correspondence Signing of Ministerial Letters Drafting for Ministers Annex 2.A – Phil Woolas Template Annex 2.B – Meg Hillier Template Annex 2.C – Home Secretary Template Annex 2.D – Chief Executive Template Annex 2.E – Home Secretary Stop List Chapter 3 – Advice on Official Replies Use of Official Reply Template Drafting Official Replies Signing Official Replies Annex 3.A – Official Reply Template Chapter 4 – Third Party Replies What is a third party? MPs acting on behalf of a relative of an applicant -

Walking Together Or Divided Agenda? Comparing Landmines and Small-Arms Campaigns

Walking Together or Divided Agenda? Comparing Landmines and Small-Arms Campaigns STEFAN BREM & KEN RUTHERFORD* Center for International Studies, Zurich, Switzerland, and Department of Political Science, Southwest Missouri State University, Springfield, MO, USA Introduction UST AS THE 19TH CENTURY closed with the 1899 Hague Peace Confer- ence, where 26 governments were represented, the 20th century ended with Jthe 1999 Hague Appeal for Peace (HAP) Conference, where the delegates represented more than 1,000 nongovernmental organizations (NGOs). The HAP Conference delegates took special pride in the entry into force on 1 March 1999 of the NGO-inspired Ottawa Treaty banning anti-personnel landmines (APMs). During the conference (11–15 May 1999), the International Action Network on Small Arms (IANSA) was launched, a coalition of interna- tional NGOs calling for the prevention of ‘proliferation and unlawful use of light weapons’.1 The IANSA and other NGO campaigns that started in The Hague held up the International Campaign to Ban Landmines (ICBL), a coali- tion of more than 1,300 NGOs from 70 countries, as an example of how to work with medium-sized states on security issues – even in opposition to ma- jor powers, such as the United States, China, and Russia. With the ICBL’s encouragement and support, the Canadian government and other pro-ban states called for the creation of a new regime, to be negotiated outside the consensus-based format of UN multilateral arms control fora. The main distinguishing features of the negotiations begun as a result of this were that they were guided by majority-voting procedures, and NGOs were welcome participants.