Farming the Rock: the Evolution of Commercial Agriculture Around St

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Constituency Allowance 01-Apr-18 to 31-Mar-19

House of Assembly Newfoundland and Labrador Member Accountability and Disclosure Report Constituency Allowance 01-Apr-18 to 31-Mar-19 MICHAEL, LORRAINE, MHA Page: 1 of 1 Summary of Transactions Processed to Date for Fiscal 2018/19 Expenditure Limit (Net of HST): $2,609.00 Transactions Processed as of: 31-Mar-19 Expenditures Processed to Date (Net of HST): $281.05 Funds Available (Net of HST): $2,327.95 Percent of Funds Expended to Date: 10.8% Date Source Document # Vendor Name Expenditure Details Amount 05-Apr-18 MECMS1037289 Seniors NL Description: Dinner with Constituents 35.09 19-Apr-18 MECMS1037289 Bishop Field School Description: dinner with Constituents 46.26 03-Dec-18 MECMS1060515 Belbins Description: Drinks for a Constitueny gathering - Challker Place Community 99.70 Centre 19-Feb-19 MECMS1067054 CSC NL Description: Annual Volunteerism Luncheon 56.14 08-Mar-19 MECMS1067054 PSAC Description: International Womens Day Luncheon 43.86 Period Activity: 281.05 Opening Balance: 0.00 Ending Balance: 281.05 ---- End of Report ---- House of Assembly Newfoundland and Labrador Member Accountability and Disclosure Report Travel & Living Allowances - Intra & Extra-Constituency Travel 01-Apr-18 to 31-Mar-19 MICHAEL, LORRAINE, MHA Page: 1 of 2 Summary of Transactions Processed to Date for Fiscal 2018/19 Expenditure Limit (Net of HST): $5,217.00 Transactions Processed as of: 31-Mar-19 Expenditures Processed to Date (Net of HST): $487.74 Funds Available (Net of HST): $4,729.26 Percent of Funds Expended to Date: 9.3% Date Source Document # Vendor Name Expenditure Details Amount 12-Apr-18 MECMS1037633 I&EConst Priv Vehicle Usage - Description: Confederation Building to Mt Pearl - 11.00 return 13-Apr-18 MECMS1037633 I&EConst Priv Vehicle Usage - Description: Confederation Building - Quidi - Vidi 5.18 - return 17-Apr-18 MECMS1037633 I&EConst Priv Vehicle Usage - Description: Mt. -

Memorial University of Newfoundland International Student Handbook 2016-2017

Memorial University of Newfoundland International Student Handbook 2016-2017 Hello and welcome! The Internationalization Office (IO) provides services to help international students adjust to university life. This guide contains information to help you – from those first few days on campus and throughout your university career. Please drop by our office any time! We are located in Corte Real, Room 1000A. NOTE: The information provided in this handbook is accurate as of June 2016, however, the content is subject to change. Internationalization Office Memorial University of Newfoundland 2016 1 | Page 2016-2017 INTERNATIONAL STUDENT HANDBOOK Welcome to Memorial University! The mission of the Internationalization Office is to coordinate on-campus services for international students in areas such as, but not limited to: settlement, immigration, health insurance, income tax, housing, and social integration. Our staff looks forward to meeting you: Juanita Hennessey is an International Student Advisor responsible for outreach services. Juanita is available to meet with students, one-on-one to discuss personal issues. She also coordinates our weekly social groups: Discussion Group and Coffee Club. Natasha Clark is an International Student Advisor responsible for health insurance and immigration advising. All registered international students are automatically enrolled in a Foreign Health Insurance Plan. As an international student you should understand your mandatory health insurance as well as other options for insurance. As a regulated immigration consultant, Natasha can meet with you to answer questions you have about your temporary immigration status in Canada. Valeri Pilgrim is an International Student Advisor responsible for the Arrivals Program (including Airport Greeter Service) and Off-Campus Housing. -

Quidi Vidi Lake NF022 Site: Newfoundland And

Site: NF022 Quidi Vidi Lake Newfoundland and Labrador Important Bird and Biodiversity Areas of Canada Zones importantes pour la 10 conservation des oiseaux et de la biodiversité du Canada V i r g i n http://www.ibacanada.org /site .jsp?site ID=NF022 i a R i v e r 20 St. John's Legend Légende Ge ne ralize d IBA boundary Lim ite g énérale de la ZICO Quidi Vidi Ex pre ssway or hig hway Autoroute ou route nationale Harbour Re g ional or local road Route rég ionale ou locale Rail line Che m in de fe r U tility corridor Lig ne de transport d'éne rg ie Contour line (m ) Courbe de nive au (m ) NF022 Wate rcourse Rivière ou ruisse au De ciduous fore st (de nse ) Forêt de fe uillus (de nse ) De ciduous fore st (ope n) Forêt de fe uillus (ouve rt) Conife rous fore st (de nse ) Forêt de conifère s (de nse ) Conife rous fore st (ope n) Forêt de conifère s (ouve rt) Mix e dwood fore st (de nse ) Forêt m ix te (de nse ) MIx e dwood fore st (ope n) Forêt m ix te (ouve rt) Shrubland Milie u arbustif We tland Milie u hum ide Othe r fore st / woodland Autre forêt er Grasse s, se dg e s or he rbs Gram m inée s, de care x , d'he rbe s iv Barre n or sparse ly ve g e tate d Dénudé se c ou vég étation clairse m ée 40 s R ie' Ag riculture / ope n country Milie u ag ricole nn Re De ve lope d are a Zone déve loppée Snow / ice Ne ig e / g lace Wate r Eau U nclassifie d Non classifié Topog raphic data / Donnée s topog raphique s © Natural Re source s Canada / © Re ssource s nature lle s Canada Cartog raphic production by Bird Studie s Canada - [email protected] Production cartog raphique par Étude s d'oise aux Canada - [email protected] 30 The IBA Prog ram is an inte rnational conse rvation initiative Le prog ram m e de s ZICO e st une initiative de conse rvation inte rnationale coordinate d by BirdLife Inte rnational. -

Traffic Impact Study Pleasantville Redevelopment St

c Road & Traffic Management nti tla A Traffic Engineering Specialists Traffic Impact Study Pleasantville Redevelopment St. John's, NL Prepared for Tract Consulting Inc. St. John's, NL and Canada Lands Company Limited December 2008 0737 Traffic Impact Study - Pleasantville Redevelopment St. John’s, Newfoundland [This page is intentionally blank] Atlantic Road & Traffic Management December 2008 +fll' nii;:irii tl:':,,.r,,i Phone (902)443-7747 PO Box 25205 Fax (902)443-7747 HALIFAXNS B3M4H4 [email protected] December3 1, 2008 Mr. Neil Dawe, President Tract Consulting lnc. 100 LemarchantRoad St. JohnsNL AIC 2H2 RE: Traffic Impact Study - Pleasantville Redevelopment, St. John's, Newfoundland Dear Mr. Dawe: I am pleasedto provide the final report for the Traffic Impact Study - Pleasuntville Redevelopment - St. John's, Newfoundland. While the Report is basedon a mixed use developmentconcept plan which included 987 residential units and 148,000square feet of commercial space,it is understoodthat the current conceptplan has been revised to include 958 residentialunits and about 62,500 squarefeet of commercial space. Since both residential and commercial land use intensitiesincluded in the current conceptplan are lessthan thoseused in the Traffic Impact Study, the conclusionsand recommendationsincluded in the Report are still consideredto be valid. If you have questions,or require additional information, please contact me by Email or telephone 902-443-7747 . Sincerely: .f .l t! ,l -. ,f .i/ J -ff ..Ji+J'? Flrqt}\rilJ$brOF IVEWFOU *$fl*"d-"*-""-"-'- ,l''"t1"" Ken O'Brien, P. Eng. ffTAITTICROAD ANN TRAFF|( IIIAI*AGETEIIT T6'or@ - ln Newfoundlar:Jand Labrador.-- Permitno. as issueo ov ACEGiuLo,tI6 wltlchis validfor they6ar aoo B- Traffic Impact Study - Pleasantville Redevelopment St. -

Regular Meeting August 24, 2009

August 24th, 2009 The Regular Meeting of the St. John’s Municipal Council was held in the Council Chamber, City Hall, at 4:30 p.m. today. His Worship Mayor O’Keefe presided There were present also Deputy Mayor Ellsworth; Councillors Duff, Colbert, Hickman, Hann, Puddister, Galgay, Coombs, Hanlon and Collins The Chief Commissioner and City Solicitor, the Associate Commissioner/Director of Corporate Services and City Clerk; the Director of Recreation; the Acting Director of Engineering, the Acting Director of Planning, and Manager, Corporate Secretariat were also in attendance. Call to Order and Adoption of the Agenda SJMC2009-08-24/477R It was decided on motion of Councillor Collins; seconded by Councillor Galgay: That the Agenda be adopted as presented with the following additional item: a. Media Release – Holland America’s Maasdam to Return to St. John’s Adoption of Minutes SJMC2009-08/24/478R It was decided on motion of Councillor Duff; seconded by Councillor Hickman: That the Minutes of the August 10th, 2009 meeting be adopted as presented. Resident vs Non Resident Registration Procedures Councillor Duff referred to the above noted item which is contained in the Parks and Recreation Committee Report dated August 13th, 2009, forming part of today’s agenda. The Director of Recreation then outlined for the general public the process with respect to the Recreation Programs Registration changes. When registering for Fall 2009 Recreation Programs residents can register beginning 7 am on Thursday, August 27, - 2 - 2009-08-24 2009. Non residents can register beginning 7 am on Thursday, September 3, 2009. All individuals registering for Fall 2009 Recreation Programs must provide photo identification stating their permanent address. -

Steep Yourself in Inuit Culture This Month

OCTOBER 2016 / ST. JOHN’S / ISSUE 33 PAGE 16 STEEP YOURSELF IN INUIT CULTURE THIS MONTH 2 / OCTOBER 2016 / THE OVERCAST www.katingavik.com A Three-day celebration of Inuit creativity in film, music and visual arts. Performances, screenings, exhibitions and concerts by Inuit artists, tradition- , bearers and their collaborators at venues across St.John s. Many events are free. Performances Demonstrations Pillorikput Inuit Oct 8, The Kirk | 7pm Kakiniq: Inuit Tattooing with Marjorie Tahbone Karrie Obed | Deantha Edmunds | Nain Brass Band Oct 8, Rocket Room | 2pm Inuit Rock Oct 8, The Ship | 10pm Traditional Inuit Games with Dion Metcalfe Twin Flames | IVA | Sun Dogs Oct 8, Rocket Room | noon Nunatsiavut Jam Oct 9, Rocket Room | noon-2PM Exhibits Screenings Arctic Impressions Oct 8 & 9, Rocket Room Sol Oct 9, LSPU Hall | 8pm Inuit Art & Craft Pop-up Sale Sat OcT 8, Innovation Hall Atrium | 12:30pm-2:30pm Inuit docs Oct 8-10, Suncor Energy Hall | Sun Oct 9, Rocket Room | 10am-noon throughout the day (8.30am - 6:00pm) and much more... More than 400 Inuit tradition-bearers, community leaders, researchers and policy-makers gather to exchange knowledge and share Inuit culture. HOSTED BY TH E NUN ATSIAVUT GOVERN MEN T WITH G E N EROUS SUPPORT FROM DISCUSSIONS, ROUNDTABLES & WORKSHOPS: • Inuit culture and language • northern housing and food security OCTO BER 8 FRO M 5 PM TO L A TE • self-determination & resource management 25 LOCATIONS AROUND DOWNTOWN ST. JOHN’S • education • traditional culture in a digital world KEYNOTE SPEAKERS • Natan Obed (Nunatsiavut), President of Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami • Tanya Tagaq (Nunavut), Performance Artist • Joar Nango (Samiland), Architect iNuit blanche is an all-Inuit art crawl through the • Natalia Radunovich (Chukotka), Linguist heart of downtown St. -

St. John's Visitorinformation Centre 17

Admirals' Coast ista Bay nav Baccalieu Trail Bo Bonavista ± Cape Shore Loop Terra Nova Discovery Trail Heritage Run-To Saint-Pierre et Miquelon Irish Loop Port Rexton Trinity Killick Coast Trans Canada Highway y a B Clarenville-Shoal Harbour y it in r T Northern Bay Goobies y Heart's a B n Content o ti p e c n o C Harbour Arnold's Cove Grace Torbay Bell Harbour Cupids Island \!St. John's Mille Brigus Harbour Conception Mount Pearl Breton Bay South y Whitbourne Ba Fortune Argentia Bay Bulls ay Witless Bay y B err ia F nt n ce lo Marystown la e Grand Bank P u q i Fortune M t Burin e Ferryland e r r St. Mary's e St. Lawrence i y P a - B t 's n i Cape St. Mary's ry a a Trepassey M S t. S rry Nova Scotia Fe ssey B pa ay Cape Race re T VIS ICE COUNT # RV RD ST To Bell Island E S T T Middle R O / P R # T I Pond A D A o I R R W P C E 'S A O N Y G I o R B n T N B c H A O e R 50 E D p M IG O O ti E H I o S G D n S T I E A A B N S R R G C a D y E R R S D ou R th Left Pon T WY # St. John's o R H D E R T D U d r T D a H SH S R H T n IT U E R Left To International # s G O O M M V P C R O R a S A AI Y E B R n D T Downtown U G Airport h a A R c d R a L SEY D a H KEL N e R B ig G y hw OL D ve a DS o b ay KIWAN TO r IS N C o ST E S e T T dl o id T City of M MAJOR 'SP AT Oxen Po Pippy H WHIT Mount Pearl nd E ROSE A D L R L Park L P A Y A N P U D S A IP T P IN L 8 1 E 10 ST R D M OU NT S CI OR K D E O NM 'L E O EA V U M A N RY T O A N R V U D E E N T T E 20 D ts S RI i DG F R C E R O IO D E X B P 40 im A L A ST PA L V K DD E C Y O A D y LD R O it P A ENN -

Population and Economy: Geographical Perspectives on Newfoundland in 1732

Document generated on 09/25/2021 1:47 p.m. Newfoundland Studies Population and Economy Geographical Perspectives on Newfoundland in 1732 John Mannion Volume 28, Number 2, Fall 2013 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/nflds28_2art03 See table of contents Publisher(s) Faculty of Arts, Memorial University ISSN 1719-1726 (print) 1715-1430 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Mannion, J. (2013). Population and Economy: Geographical Perspectives on Newfoundland in 1732. Newfoundland Studies, 28(2), 219–265. All rights reserved © Memorial University, 2013 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ Population and Economy: Geographical Perspectives on Newfoundland in 1732 JOHN MANNION On 27 April 1732 the Duke of Newcastle informed the Council of Trade and Plantations in London that the King had approved the appointment of Edward Falkingham as governor of Newfoundland. Falkingham had been a captain in the Royal Navy since 1713, and already had served as a commodore on the Newfoundland station.1 In mid-May 1732 the Admiralty requested and re- ceived copies of Falkingham’s Commission and Instructions, including the traditional “Heads of Inquiry,” a detailed list of questions on the state of the fishery.2 Focusing primarily on the cod economy, the queries also covered a wide range of demographic and social aspects of life on the island, particularly during the summer. -

Year Book and Almanac of Newfoundland

: APPENDIX. (Corrected to Gazette of January 32nd, 1918.) COLONY OF NEWFOUNDLAND-page 17, For Colony, read Dominion. GOVERNMENT HOUSE-page 17. Add—Private Secretary—Lt. Col. H. W. Knox-Niven. Add—Aide-de-Camp—Capt. J. H. Campbell. EXECUTIVE COUNCIL-page 17. For the Executive Council and Departmental Officers, read Hon. W. F. Lloyd, K.C., D.C.L., Prime Minister and Minister of Justice. W. W. Halfyard, Colonial Secretary (acting). M. P. Cashin, Minister of Finance and Customs. J. A. Clift, K.C., Minister of Agriculture and Mines (acting). W. Woodford, Minister of Public Works. J. Crosbie, Minister of Shipping (acting). W. F. Coaker, 1 A. E. Hickman, > Without portfolio. W. J. Ellis, ) Departmental Officers not in Cabinet. John G. Stone, Minister of Marine and Fisheries. John R. Bennett, Minister of Militia (acting.). LEGISLATIVE COXJNCIL-page 17. Add— Ron. W. J. Ellis. HOUSE OF ASSEMBLY—page 19. ^f^^—Clapp, W. M.— St. Barbe. Devereux, R. J. — Placentia and St. Mary's. Goodison, J. R. —Carbonear. Morine, A. B., K.C. — Bonavista. Morris, F. J., K.C— Placentia and St. Mary's. Owi^-Morris, Rt. Hon. Sir E. P., P.O., K.C.M.G.—St: John's West. Prime Minister's Office—page 21. Prime Minister—For Rt. Hon. K. P. Morris, read Hon. W. F. Lloyd, K.C, D.C.L. Colonial Secretary's Office—page 21. Colonial Secretary—For Hon. R. A. Squires, K.C, read Hon. W. W. Halfyard (acting). After A. Mews, J.P., add C.M.G. Agriculture and Mines—page 2(Xi. Minister of Agriculture and Mines—For Hon. -

Quidi Vidi Village Development Plan

FINAL DRAFT FINAL DRAFT FINAL DRAFT FINAL DRAFT Table of Contents CONTEXT ............................................................................................................................................................. 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................................................................................... 2 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................................... 4 SECTION A: DEVELOPMENT PLAN RECOMMENDATIONS A.1 Quidi Vidi Pierwalk ........................................................................................................................ 8 A.2 General Store and Visitor Centre (Eli’s Wharf) ............................................................................ 11 A.3 Neighbourhood Playground ........................................................................................................... 13 A.4 Quidi Vidi Pass Battery .................................................................................................................. 14 A.5 Cascade Park .................................................................................................................................. 15 SECTION B: VILLAGE WIDE INITIATIVES / PLANNING CONSIDERATIONS B.1 Pedestrian Circulation Enhancement and Interpretation .............................................................. 17 B.2 Vehicular Circulation / Parking Opportunities ............................................................................. -

Proposal Public Hearings.Pdf

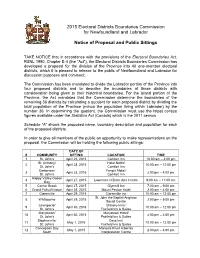

2015 Electoral Districts Boundaries Commission for Newfoundland and Labrador Notice of Proposal and Public Sittings TAKE NOTICE that in accordance with the provisions of the Electoral Boundaries Act, RSNL 1990, Chapter E-4 (the “Act”), the Electoral Districts Boundaries Commission has developed a proposal for the division of the Province into 40 one-member electoral districts, which it is pleased to release to the public of Newfoundland and Labrador for discussion purposes and comment. The Commission has been mandated to divide the Labrador portion of the Province into four proposed districts and to describe the boundaries of those districts with consideration being given to their historical boundaries. For the island portion of the Province, the Act mandates that the Commission determine the boundaries of the remaining 36 districts by calculating a quotient for each proposed district by dividing the total population of the Province (minus the population living within Labrador) by the number 36. In determining the quotient, the Commission must use the latest census figures available under the Statistics Act (Canada) which is the 2011 census. Schedule “A” shows the proposed name, boundary description and population for each of the proposed districts. In order to give all members of the public an opportunity to make representations on the proposal, the Commission will be holding the following public sittings: DATE OF # COMMUNITY SITTING LOCATION TIME 1 St. John’s April 22, 2015 Comfort Inn 10:00 am – 4:00 pm St. Anthony/ Hotel North/ 2 April 23, 2015 10:00 am – 12:00 pm St. John’s Comfort Inn Carbonear/ Fong’s Motel/ 3 April 23, 2015 2:00 pm – 4:00 pm St. -

The Status of Bank Swallow (Riparia Riparia Riparia)

The Status of Bank Swallow (Riparia riparia riparia) in Newfoundland and Labrador Photo by “Myosotis Scorpioides”; from en.wikipedia. Used by permission under Creative Commons Attribution ShareAlike 3.0 License THE SPECIES STATUS ADVISORY COMMITTEE REPORT NO. 23 October 14, 2009 1 RECOMMENDED STATUS Recommended status: Current designation: Not at Risk None Criteria met: None Reasons for designation: Even though populations of this species appear to be experiencing declines in some neighboring jurisdictions, there is insufficient evidence to establish that the species is presently at risk in Newfoundland and Labrador The original version of this report was prepared by Kathrin J. Munro and was subsequently edited by the Species Status Advisory Committee. 2 STATUS REPORT Riparia riparia riparia (Linnaeus, 1758) Bank Swallow; Hirondelle de ravage, Sand Martin Family: Hirundinidae (Swallows) Life Form: Bird (Aves) Systematic/Taxonomic Clarifications: There are three recognized subspecies of Bank Swallow. R. r. riparia (Linnaeus, 1758): Breeds throughout North America, Eurasia, Mediterranean region, and northwestern Africa; winters in Central and South America and Africa (Cramp et al., 1988). R. r. diluta (Sharpe and Wyatt, 1893): Breeds from Siberia and western Mongolia south to eastern Iran, Afghanistan, northern India, and southeastern China. Vagrant to arctic North America and Bermuda (Phillips, 1986). R. r. shelleyi (Sharpe, 1885): Breeds in lower Egypt with winter grounds in northeastern Africa. Riparia riparia riparia is the subject