An Analysis of the Compositional Practices of Ornette Coleman As Demonstrated in His Small Group Recordings During the 1970S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Original Works Festival 2009 Program Two

NEW ORIGINAL WORKS FESTIVAL 2009 PROGRAM TWO July 30 – August 1, 2009 8:30pm presented by REDCAT Roy and Edna Disney/CalArts Theater California Institute of the Arts NOW FESTIVAL 2009: PROGRAM TWO NEW ORIGINAL WORKS FESTIVAL 2009 UPCOMING PERFORMANCES August 6 – August 8 : Program Three 1 CAROLE KIM W/ OGURI, ALEX CLINE AND DAN CLUCAS: N Zackary Drucker / Mariana Marroquin / Wu Ingrid Tsang: PIG direction and video installation: Carole Kim Meg Wolfe: Watch Her (Not Know It Now) dance: Oguri Lauren Weedman: Off percussion: Alex Cline winds: Dan Clucas live-feed video: Adam Levine and Moses Hacmon lighting design: Chris Kuhl I. Reflect --he vanishes Into the skin of water... ...And leaves me with my arms full of nothing But water and the memory of an image? ...The one I loved should be let live. He should live on after me, blameless.’ [Tales from Ovid, Hughes] II. Hall of Mirrors The black mirror is a surface, but this surface is also a depth. This specular catastrophe, prefigured by the myth of Narcissus, is inseparable from a process that renders the gaze opaque. [The Claude Glass: Use and Meaning of the Black Mirror in Western Art, Arnaud Maillet] III. Syphon IV. Shade This mirror creates, as it were, a hole in the wall, a door into the realm of the dead. But it also constitutes an epiphany, since the divinity is seen in all its glory and clarity. [Maillet] Improvising … hinges on one’s ability to synchronize intention and action and to maintain a keen awareness of, sensitivity to, and connection with the evolving group dynamics and experiences. -

Wavelength (December 1981)

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO Wavelength Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies 12-1981 Wavelength (December 1981) Connie Atkinson University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/wavelength Recommended Citation Wavelength (December 1981) 14 https://scholarworks.uno.edu/wavelength/14 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies at ScholarWorks@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wavelength by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ML I .~jq Lc. Coli. Easy Christmas Shopping Send a year's worth of New Orleans music. to your friends. Send $10 for each subscription to Wavelength, P.O. Box 15667, New Orleans, LA 10115 ·--------------------------------------------------r-----------------------------------------------------· Name ___ Name Address Address City, State, Zip ___ City, State, Zip ---- Gift From Gift From ISSUE NO. 14 • DECEMBER 1981 SONYA JBL "I'm not sure, but I'm almost positive, that all music came from New Orleans. " meets West to bring you the Ernie K-Doe, 1979 East best in high-fideUty reproduction. Features What's Old? What's New ..... 12 Vinyl Junkie . ............... 13 Inflation In Music Business ..... 14 Reggae .............. .. ...... 15 New New Orleans Releases ..... 17 Jed Palmer .................. 2 3 A Night At Jed's ............. 25 Mr. Google Eyes . ............. 26 Toots . ..................... 35 AFO ....................... 37 Wavelength Band Guide . ...... 39 Columns Letters ............. ....... .. 7 Top20 ....................... 9 December ................ ... 11 Books ...................... 47 Rare Record ........... ...... 48 Jazz ....... .... ............. 49 Reviews ..................... 51 Classifieds ................... 61 Last Page ................... 62 Cover illustration by Skip Bolen. Publlsller, Patrick Berry. Editor, Connie Atkinson. -

A Conversation with Petra Haden by Frank Goodman (Puremusic.Com, 1/2009)

A Conversation with Petra Haden by Frank Goodman (Puremusic.com, 1/2009) A short while back, we interviewed a fascinating accordionist, music-oriented photographer, and image and scene maker in Portland named Alicia J. Rose, aka Miss Murgatroid. She'd taken very compelling photos of several bands we'd covered (Sophe Lux and Boy Eats Drum Machine come to mind), and then we stumbled on to her signature accordion work, which often involved multiple effects pedals. Her best known CD was one she'd woven with her friend and musical partner Petra Haden. Although you might know Petra as a member of the Decemberists, or as one of Charlie Haden's daughters (the legendary jazz bassist), or the guest soloist in any of many bands (including the recent Foo Fighters tour), she is still and deservedly best known for her a capella version of the entire Sell Out record by The Who. (She later cut a record with Bill Frisell that happens to be rather divine, called simply Petra Haden and Bill Frisell.) But the Petra project that ignited our conversation was Hearts and Daggers, the long awaited and satisfying reunion with Miss Murgatroid. Some sounds are best heard before described, and you'll find the customary links to those audio clips along the way. We're sure you'll find Petra's words interesting, as we certainly did. And thanks to Miss Murgatroid, aka Alicia J. Rose, who led us here. Puremusic: Let's talk first about this recent release with Miss Murgatroid, Hearts and Daggers. We like that a lot. -

Johnny O'neal

OCTOBER 2017—ISSUE 186 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM BOBDOROUGH from bebop to schoolhouse VOCALS ISSUE JOHNNY JEN RUTH BETTY O’NEAL SHYU PRICE ROCHÉ Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East OCTOBER 2017—ISSUE 186 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 NEw York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : JOHNNY O’NEAL 6 by alex henderson [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : JEN SHYU 7 by suzanne lorge General Inquiries: [email protected] ON The Cover : BOB DOROUGH 8 by marilyn lester Advertising: [email protected] Encore : ruth price by andy vélez Calendar: 10 [email protected] VOXNews: Lest We Forget : betty rochÉ 10 by ori dagan [email protected] LAbel Spotlight : southport by alex henderson US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or VOXNEwS 11 by suzanne lorge money order to the address above or email [email protected] obituaries Staff Writers 12 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Fred Bouchard, Festival Report Stuart Broomer, Robert Bush, 13 Thomas Conrad, Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Phil Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, special feature 14 by andrey henkin Anders Griffen, Tyran Grillo, Alex Henderson, Robert Iannapollo, Matthew Kassel, Marilyn Lester, CD ReviewS 16 Suzanne Lorge, Mark Keresman, Marc Medwin, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, Miscellany 41 John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Andrew Vélez, Scott Yanow Event Calendar Contributing Writers 42 Brian Charette, Ori Dagan, George Kanzler, Jim Motavalli “Think before you speak.” It’s something we teach to our children early on, a most basic lesson for living in a society. -

Cobham Bellson.Sell.4

Pre-order date: Feb. 20, 2007 DVD NEW RELEASES Street date: Mar. 6, 2007 TIMELESS JAZZ LEGENDS from V.I.E.W. GIL EVANS AND HIS ORCHESTRA GIL EVANS View DVD #2301 – List Price $19.98 Gil Evans, one of the most notable arrangers and composers of the 20th century, with Randy and Michael Brecker, lent his conducting talents to jazz great Miles Davis (creating the landmark Billy Cobham, Lew Soloff, Birth of Cool) and played with the “Who’s Who” of jazz history. From collab- Herb Geller, Howard Johnson orating with Charlie Parker and Cannonball Adderley, to Art Blakey and Gerry and Mike Manieri Mulligan, Evans’ name is synonymous with jazz excellence. In this exclusive concert performance on DVD, Gil Evans leads an all-star band, which includes Randy and Michael Brecker, Billy Cobham, Lew Soloff and Mike Manieri. Song selections include Hotel Me, Stone Free, Here Comes de Honey Man, DVD BONUS FEATURES Friday the 13th and more. ➤ Gil Evans Biography ➤ Michael Brecker Biography “Yes, he definitely is the best.” –Miles Davis ➤ Randy Brecker Biography ➤ Billy Cobham Biography 57 minutes plus Multiple Bonus Features ➤ Gil Goldstein Biography VIEW DVD #2301 $19.98 VIEW VHS #1301 $19.98 ➤ Howard Johnson Biography ➤ Mike Manieri Biography ➤ Lew Soloff Biography ISBN 0-8030-2301-4 ➤ Instant Access to Songs and Solos “Yes, he definitely is the best.” –Miles Davis ➤ Digitally Re-mastered Audio and Video ➤ Dolby Stereo Audio 0 33909 23019 3 ➤ DVD Recommendations 40 YEARS OF MJQ View DVD #2350 – List Price $19.98 The distinguished Modern Jazz Quartet traces its origins to the irrepressibly YEARS OF flamboyant Dizzy Gillespie and his brazzy, shouting bebop big band. -

Drums • Bobby Bradford - Trumpet • James Newton - Flute • David Murray - Tenor Sax • Roberto Miranda - Bass

1975 May 17 - Stanley Crouch Black Music Infinity Outdoors, afternoon, color snapshots. • Stanley Crouch - drums • Bobby Bradford - trumpet • James Newton - flute • David Murray - tenor sax • Roberto Miranda - bass June or July - John Carter Ensemble at Rudolph's Fine Arts Center (owner Rudolph Porter)Rudolph's Fine Art Center, 3320 West 50th Street (50th at Crenshaw) • John Carter — soprano sax & clarinet • Stanley Carter — bass • William Jeffrey — drums 1976 June 1 - John Fahey at The Lighthouse December 15 - WARNE MARSH PHOTO Shoot in his studio (a detached garage converted to a music studio) 1490 N. Mar Vista, Pasadena CA afternoon December 23 - Dexter Gordon at The Lighthouse 1976 June 21 – John Carter Ensemble at the Speakeasy, Santa Monica Blvd (just west of LaCienega) (first jazz photos with my new Fujica ST701 SLR camera) • John Carter — clarinet & soprano sax • Roberto Miranda — bass • Stanley Carter — bass • William Jeffrey — drums • Melba Joyce — vocals (Bobby Bradford's first wife) June 26 - Art Ensemble of Chicago Studio Z, on Slauson in South Central L.A. (in those days we called the area Watts) 2nd-floor artists studio. AEC + John Carter, clarinet sat in (I recorded this on cassette) Rassul Siddik, trumpet June 24 - AEC played 3 nights June 24-26 artist David Hammond's Studio Z shots of visitors (didn't play) Bobby Bradford, Tylon Barea (drummer, graphic artist), Rudolph Porter July 2 - Frank Lowe Quartet Century City Playhouse. • Frank Lowe — tenor sax • Butch Morris - drums; bass? • James Newton — cornet, violin; • Tylon Barea -- flute, sitting in (guest) July 7 - John Lee Hooker Calif State University Fullerton • w/Ron Thompson, guitar August 7 - James Newton Quartet w/guest John Carter Century City Playhouse September 5 - opening show at The Little Big Horn, 34 N. -

The Titles Below Are Being Released for Record Store

THE TITLES BELOW ARE BEING RELEASED FOR RECORD STORE DAY (v.2.2 updated 4-01) ARTISTA TITOLO FORMATO LABEL LA DONNA IL SOGNO & IL GRANDE ¢ 883 2LP PICTURE WARNER INCUBO ¢ ACID MOTHERS TEMPLE NAM MYO HO REN GE KYO LP SPACE AGE ¢ AL GREEN GREEN IS BLUES LP FAT POSSUM ¢ ALESSANDRO ALESSANDRONI RITMO DELL’INDUSTRIA N°2 LP BTF ¢ ALFREDO LINARES Y SU SONORA YO TRAIGO BOOGALOO LP VAMPISOUL LIVE FROM THE APOLLO THEATRE ¢ ALICE COOPER 2LP WARNER GLASGOW, FEB 19, 1982 SOUNDS LIKE A MELODY (GRANT & KELLY ¢ ALPHAVILLE REMIX BY BLANK & JONES X GOLD & 12" WARNER LLOYD) HERITAGE II:DEMOS ALTERNATIVE TAKES ¢ AMERICA LP WARNER 1971-1976 ¢ ANDREA SENATORE HÉRITAGE LP ONDE / ITER-RESEARCH ¢ ANDREW GOLD SOMETHING NEW: UNREALISED GOLD LP WARNER ¢ ANNIHILATOR TRIPLE THREAT UNPLUGGED LP WARNER ¢ ANOUSHKA SHANKAR LOVE LETTERS LP UNIVERSAL ¢ ARCHERS OF LOAF RALEIGH DAYS 7" MERGE ¢ ARTICOLO 31 LA RICONQUISTA DEL FORUM 2LP COLORATO BMG ¢ ASHA PUTHLI ASHA PUTHLI LP MR. BONGO ¢ AWESOME DRE YOU CAN'T HOLD ME BACK LP BLOCGLOBAL ¢ BAIN REMIXES 12'' PICTURE CIMBARECORD ¢ BAND OF PAIN A CLOCKWORK ORANGE LP DIRTER ¢ BARDO POND ON THE ELLIPSE LP FIRE ¢ BARRY DRANSFIELD BARRY DRANSFIELD LP GLASS MODERN ¢ BARRY HAY & JB MEIJERS THE ARTONE SESSION 10" MUSIC ON VINYL ¢ BASTILLE ALL THIS BAD BLOOD 2LP UNIVERSAL ¢ BATMOBILE BIG BAT A GO-GO 7'' COLORATO MUSIC ON VINYL I MISTICI DELL'OCCIDENTE (10° ¢ BAUSTELLE LP WARNER ANNIVERSARIO) ¢ BECK UNEVENTFUL DAYS (ST. VINCENT REMIX) 7" UNIVERSAL GRANDPAW WOULD (25TH ANNIVERSARY ¢ BEN LEE 2LP COLORATO LIGHTNING ROD DELUXE) ¢ BEN WATT WITH ROBERT WYATT SUMMER INTO WINTER 12'' CHERRY RED ¢ BERT JANSCH LIVE IN ITALY LP EARTH ¢ BIFFY CLYRO MODERNS 7'' COLORATO WARNER ¢ BLACK ARK PLAYERS GUIDANCE 12'' PICTURE VP GOOD TO GO ¢ BLACK LIPS FEAT. -

Roberto Miranda Dewey Johnson

ENCORE played all those instruments and he taught those taught me.” instruments to me and my brother. One of the Miranda recalls that he made his first recording at ROBERTO favorite memories I have of my life is watching my age 21 with pianist Larry Nash and drummer Woody parents dance to Latin music. Man! That still is an “Sonship” Theus, who were both just 16 at the time. incredible memory.” The name of the album was The Beginning and it also Years later in school, his brother played percussion featured saxophonists Herman Riley and Pony MIRANDA in concert band and Miranda asked for a trumpet. All Poindexter and trumpeter Luis Gasca (who, under those chairs were taken, he was told, so he requested contract elsewhere, used a pseudonym). The drummer by anders griffen a guitar, but was told that was not a band instrument. became a dear friend and was instrumental in Miranda They did need bass players, however, so that’s when he ending up on a record with Charles Lloyd (Waves, Bassist Roberto Miranda has been on many musical first played bass but gave it up after the semester. The A&M, 1972), even though, as it was happening, adventures, performing and recording with his brothers had formed a band together in which Louis Miranda didn’t even know he was being recorded. mentors—Horace Tapscott, John Carter and Bobby played drum set and Roberto played congas. As “Sonship Theus was a very close friend of mine. Bradford and later, Kenny Burrell—as well as artists teenagers they started a social club and held dances. -

The Evolution of Ornette Coleman's Music And

DANCING IN HIS HEAD: THE EVOLUTION OF ORNETTE COLEMAN’S MUSIC AND COMPOSITIONAL PHILOSOPHY by Nathan A. Frink B.A. Nazareth College of Rochester, 2009 M.A. University of Pittsburgh, 2012 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2016 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH THE KENNETH P. DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Nathan A. Frink It was defended on November 16, 2015 and approved by Lawrence Glasco, PhD, Professor, History Adriana Helbig, PhD, Associate Professor, Music Matthew Rosenblum, PhD, Professor, Music Dissertation Advisor: Eric Moe, PhD, Professor, Music ii DANCING IN HIS HEAD: THE EVOLUTION OF ORNETTE COLEMAN’S MUSIC AND COMPOSITIONAL PHILOSOPHY Nathan A. Frink, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2016 Copyright © by Nathan A. Frink 2016 iii DANCING IN HIS HEAD: THE EVOLUTION OF ORNETTE COLEMAN’S MUSIC AND COMPOSITIONAL PHILOSOPHY Nathan A. Frink, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2016 Ornette Coleman (1930-2015) is frequently referred to as not only a great visionary in jazz music but as also the father of the jazz avant-garde movement. As such, his work has been a topic of discussion for nearly five decades among jazz theorists, musicians, scholars and aficionados. While this music was once controversial and divisive, it eventually found a wealth of supporters within the artistic community and has been incorporated into the jazz narrative and canon. Coleman’s musical practices found their greatest acceptance among the following generations of improvisers who embraced the message of “free jazz” as a natural evolution in style. -

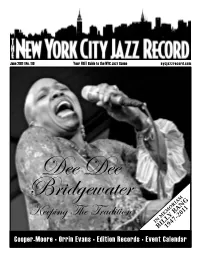

Keeping the Tradition Y B 2 7- in MEMO4 BILL19 Cooper-Moore • Orrin Evans • Edition Records • Event Calendar

June 2011 | No. 110 Your FREE Guide to the NYC Jazz Scene nycjazzrecord.com Dee Dee Bridgewater RIAM ANG1 01 Keeping The Tradition Y B 2 7- IN MEMO4 BILL19 Cooper-Moore • Orrin Evans • Edition Records • Event Calendar It’s always a fascinating process choosing coverage each month. We’d like to think that in a highly partisan modern world, we actually live up to the credo: “We New York@Night Report, You Decide”. No segment of jazz or improvised music or avant garde or 4 whatever you call it is overlooked, since only as a full quilt can we keep out the cold of commercialism. Interview: Cooper-Moore Sometimes it is more difficult, especially during the bleak winter months, to 6 by Kurt Gottschalk put together a good mixture of feature subjects but we quickly forget about that when June rolls around. It’s an embarrassment of riches, really, this first month of Artist Feature: Orrin Evans summer. Just like everyone pulls out shorts and skirts and sandals and flipflops, 7 by Terrell Holmes the city unleashes concert after concert, festival after festival. This month we have the Vision Fest; a mini-iteration of the Festival of New Trumpet Music (FONT); the On The Cover: Dee Dee Bridgewater inaugural Blue Note Jazz Festival taking place at the titular club as well as other 9 by Marcia Hillman city venues; the always-overwhelming Undead Jazz Festival, this year expanded to four days, two boroughs and ten venues and the 4th annual Red Hook Jazz Encore: Lest We Forget: Festival in sight of the Statue of Liberty. -

Stylistic Evolution of Jazz Drummer Ed Blackwell: the Cultural Intersection of New Orleans and West Africa

STYLISTIC EVOLUTION OF JAZZ DRUMMER ED BLACKWELL: THE CULTURAL INTERSECTION OF NEW ORLEANS AND WEST AFRICA David J. Schmalenberger Research Project submitted to the College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Percussion/World Music Philip Faini, Chair Russell Dean, Ph.D. David Taddie, Ph.D. Christopher Wilkinson, Ph.D. Paschal Younge, Ed.D. Division of Music Morgantown, West Virginia 2000 Keywords: Jazz, Drumset, Blackwell, New Orleans Copyright 2000 David J. Schmalenberger ABSTRACT Stylistic Evolution of Jazz Drummer Ed Blackwell: The Cultural Intersection of New Orleans and West Africa David J. Schmalenberger The two primary functions of a jazz drummer are to maintain a consistent pulse and to support the soloists within the musical group. Throughout the twentieth century, jazz drummers have found creative ways to fulfill or challenge these roles. In the case of Bebop, for example, pioneers Kenny Clarke and Max Roach forged a new drumming style in the 1940’s that was markedly more independent technically, as well as more lyrical in both time-keeping and soloing. The stylistic innovations of Clarke and Roach also helped foster a new attitude: the acceptance of drummers as thoughtful, sensitive musical artists. These developments paved the way for the next generation of jazz drummers, one that would further challenge conventional musical roles in the post-Hard Bop era. One of Max Roach’s most faithful disciples was the New Orleans-born drummer Edward Joseph “Boogie” Blackwell (1929-1992). Ed Blackwell’s playing style at the beginning of his career in the late 1940’s was predominantly influenced by Bebop and the drumming vocabulary of Max Roach. -

Jazz Piano Handbook

LISTENING Listening to master musicians is an essential part of the learning process. While there is no substitute for experiencing live music, recordings are the great textbooks for students of jazz. So, I encourage you to listen to recordings between classes, in the car, or when doing chores. In addition, focused listening, without distraction, can help you understand jazz music at a deeper level and will contribute to your overall development. Who to Listen To There are hundreds of great jazz recordings, and it can be difficult for students to know where to start. Today, you can listen to a lot of great music through services such as youtube, Pandora, and Spotify. Many libraries also have wonderful jazz collections. In addition, concerts and television appearances from classic jazz groups are now available on DVD. By their nature, lists of essential jazz recordings are somewhat arbitrary and generally incomplete; the list below is no exception. However, as a reference, I have assembled this list of some of the great jazz rhythm sections and important horn players. They are listed below in rough chronological order. Important Rhythm Sections • Count Basie/Walter Page/Jo Jones/Freddie Green (guitar) – This unit is the model for modern rhythm sections. They swing whether they are playing loud or soft. Some more modern Basie rhythm sections can be heard on Atomic Basie and Frankly Speaking. • Bud Powell/Charlie Mingus/Max Roach – This is the quintessential bebop rhythm section. A great recording featuring Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie is The Quintet: Jazz at Massey Hall. • Modern Jazz Quartet – John Lewis/Percy Heath/Connie Kay/Milt Jackson (vibes) – This quartet performed together for decades.