2012-05-09 Respondents Objection and Response to Trust Petition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mayors, Parish President Share Hopes for 2021

Today Tonight HIGH LOW Teche Action Jim Bradshaw: Steamer Was 57 38 Clinic staff receive Sucked Right Out of the Forecast COVID vaccine, River Wednesday Sunny, high near 57. Joe Guzzardi: Tight Asylum Calm wind becoming hold blood drive northwest around 5 Rules Protect the Homeland mph. Wednesday Night PAGE 6 PAGE 4 Mostly clear, with a low around 38. Calm wind. Franklin, Louisiana ‘The Voice of the Teche’ $1.00 10 Pages Volume 138, No. 8 © 2021, LSN Publishing Co., LLC Wednesday, January 13, 2021 http://www.stmarynow.com Mayors, Parish President share hopes for 2021 By CASEY COLLIER The Banner-Tribune With 2020 still freshly in America’s rearview, and its trap- pings perhaps still a bit sour on our tongues, local leaders in St. Mary Parish have already said that they intend to utilize 2021 to foster hope and progress in the parish. Franklin Mayor Eugene Foulcard mused, “In reflecting on the progress we made during 2020, we are hoping for brighter things in 2021. “With the funding we got from the parish government, we are looking to embark on overlaying a few streets, which should hopefully begin sometime around Jan. 11-14.” He said the project will include “some of the worst of the worst” streets in town, including: Elm Street, King Street, Blakesley Street, 10th Street, West Adams Street, the intersec- tion of West Adams at West Ibert Street, and the removal of the rail crossing near the former St. Mary Iron Works. He continued, “Hopefully we can continue in some of the first St. -

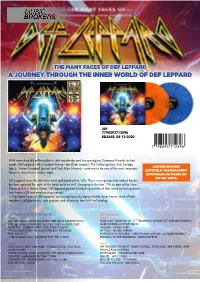

A Journey Through the Inner World of Def Leppard

THE MANY FACES OF DEF LEPPARD A JOURNEY THROUGH THE INNER WORLD OF DEF LEPPARD 2LP 7798093712896 RELEASE: 04-12-2020 With more than 65 million albums sold worldwide and two prestigious Diamond Awards to their credit, Def Leppard with its current line-up –Joe Elliott (vocals), Phil Collen (guitar), Rick Savage LIMITED EDITION (bass), Vivian Campbell (guitar) and Rick Allen (drums)— continue to be one of the most important GATEFOLD TRANSPARENT forces in rock music.n many ways, ORANGE/BLUE MARBLED 180 GR. VINYL Def Leppard were the definitive hard rock band of the ‘80s. There were groups that rocked harder, but few captured the spirit of the times quite as well. Emerging in the late ‘70s as part of the New Wave of British Heavy Metal, Def Leppard gained a following outside of that scene by toning down their heavy riffs and emphasizing melody. In The Many Faces of Def Leppard, we are going to dig deep into the lesser known work of their members, collaborations, side projects and of course, their hit-filled catalog. LP1 - THE MANY FACES OF DEF LEPPARD LP2 - THE SONGS Side A Side A ALL JOIN HANDS - ROADHOUSE FEAT. PETE WILLIS & FRANK NOON POUR SOME SUGAR ON ME - LEE THOMPSON, JOHNNY DEE, RICHARD KENDRICK, I WILL BE THERE - GOMAGOG FEAT. PETE WILLIS & JANICK GERS MARKO PUKKILA & HOWIE SIMON DOIN’ FINE - CARMINE APPICE FEAT. VIVIAN CAMPBELL HYSTERIA - DANIEL FLORES ON A LONELY ROAD - THE FROG & THE RICK VITO BAND LET IT GO - WICKED GARDEN FEAT. JOE ELLIOTT ROCK ROCK TIL YOU DROP - CHRIS POLAND, JOE VIERS & RICHARD KENDRICK OVER MY DEAD BODY - MAN RAZE FEAT. -

D:\Teora\Radu\R\Pdf\Ghid Pop Rock\Prefata.Vp

DedicaÆie: Lui Vlad Månescu PREFAæÅ Lucrarea de faÆå cuprinde câteva sute de biografii çi discografii ale unor artiçti çi trupe care au abordat diverse stiluri çi genuri muzicale, ca pop, rock, blues, soul, jaz çi altele. Cartea este dedicatå celor care doresc så-çi facå o idee despre muzica çi activitatea celor mai cunoscuÆi artiçti, mai noi çi mai vechi, de la începutul secolului çi pânå în zilele noastre. Totodatå am inclus çi un capitol de termeni muzicali la care cititorul poate apela pentru a înÆelege anumite cuvinte sau expresii care nu îi sunt familiare. Fårå a se dori o lucrare foarte complexå, aceastå micå enciclopedie oferå date esenÆiale din biografia celor mai cunoscuÆi artiçti çi trupe, låsând loc lucrårilor specializate pe un anumit gen sau stil muzical så dezvolte çi så aprofundeze ceea ce am încercat så conturez în câteva rânduri. Discografia fiecårui artist sau trupå cuprinde albumele apårute de la începutul activitåÆii çi pânå în prezent, sau, de la caz la caz, pânå la data desfiinÆårii trupei sau abandonårii carierei. Am numit disc de platinå sau aur acele albume care s-au vândut într-un anumit numår de exemplare (diferit de la Æarå la Æarå, vezi capitolul TERMENI MUZICALI) care le-au adus acest statut. Totodatå, am inclus çi o serie de LP-uri BEST OF sau GREATEST HITS apårute la casele de discuri din întreaga lume. De aceea veÆi observa cå discografia unui artist sau a unei trupe cuprinde mai multe albume decât au apårut în timpul vieÆii sau activitåÆii acestora (vezi Jimi Hendrix, de exemplu) çi asta pentru cå industria muzicalå çi magnaÆii acesteia çi-au protejat contractele çi investiÆiile iniÆiale cât mai mult posibil, profitând la maximum de numele artiçtilor çi trupelor lor. -

Waysted Vices Mp3, Flac, Wma

Waysted Vices mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Vices Country: US Released: 1983 Style: Hard Rock, Heavy Metal MP3 version RAR size: 1707 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1759 mb WMA version RAR size: 1490 mb Rating: 4.8 Votes: 646 Other Formats: VOC AA AAC MIDI MP4 DMF MMF Tracklist Hide Credits A1 Love Loaded 3:51 A2 Women In Chains 4:10 A3 Sleazy 4:18 A4 Night Of The Wolf 5:22 B1 Toy With The Passion 4:00 B2 Right From The Start 5:31 B3 Hot Love 4:18 B4 All Belongs To You 3:30 Somebody To Love B5 3:01 Written-By – G. Slick* Companies, etc. Copyright (c) – Chrysalis Records Ltd. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Chrysalis Records Ltd. Published By – Chrysalis Records Ltd. Published By – Rondor Music (London) Ltd. Produced For – Smoothside Ltd. Recorded At – Moor Hall Studios Recorded At – Parkgate Studios Mixed At – Maison Rouge Mixed At – The Town House Mastered At – Cutting Room Credits Bass – Pete Way Design – John Pasche Drums – Frank Noon Engineer [Assistant] – Dave Chapman Lead Guitar, Backing Vocals – Ronnie Kayfield Management – Part Rock Management Ltd* Management [Agency Representation North America] – Bill Elson Management [Agency Representation UK And Europe] – John Jackson Mastered By [Vinyl] – OR* Mixed By – Paul Raymond , Pete Way Other [Assistant Engineers ] – Aldo, Leigh And Alan Photography By – John Shaw Producer, Engineer, Mixed By – Mick Glossop Rhythm Guitar, Keyboards, Backing Vocals – Paul Raymond Set Designer – Paul Baker Vocals – Fin* Notes ℗ & © 1983 Chrysalis Records Ltd. Made in Sweden Barcode -

Rock Candy Magazine

MOSCOW MUSIC PEACE FESTIVAL STRICTLY OLD SCHOOL BADGES MÖTLEY CRÜE’S LAME CANCELLATION EXCUSE OLD SCHOOL BADGES MÖTLEY CRÜE’S LAME CANCELLATION STRICTLY FESTIVAL MUSIC PEACE MOSCOW COLLECTORS REMASTERED ISSUE EDITIONS & RELOADED 2 OUT NOW June–July 2017 £9.99 HARD, SWEET & STICKY LILLIAN AXE - ‘S/T’ LILLIAN AXE - ‘LOVE+WAR’ WARRANT - ‘CHERRY PIE’ WARRANT - ‘DIRTY ROTTEN FILTHY MOTHER’S FINEST - ‘IRON AGE’ STINKING RICH’ ROCK CANDY MAG ISSUE 2 JUNE – JULY 2017 ISSUE 2 JUNE – JULY MAG CANDY ROCK MAHOGANY RUSH - ‘LIVE’ FRANK MARINO - ‘WHAT’S NEXT’ FRANK MARINO FRANK MARINO - ‘JUGGERNAUT’ CREED - ‘S/T’ SURVIVOR ‘THE POWER OF ROCK AND ROLL’ ‘EYE OF THE TIGER’ KING KOBRA - ‘READY TO STRIKE’ KING KOBRA 707 - ‘S/T’ 707 - ‘THE SECOND ALBUM’ 707 - ‘MEGAFORCE’ OUTLAWS - ‘PLAYIN’ TO WIN’ ‘THRILL OF A LIFETIME’ “IT WAS LOUD – LIKE A FACTORY!” LOUD “IT WAS SAMMY HAGAR SALTY DOG TYKETTO - ‘DON’T COME EASY’ KICK AXE - ‘VICES’ KICK AXE KICK AXE - ‘ROCK THE WORLD’ ‘ALL NIGHT LONG’ ‘EVERY DOG HAS IT’S DAY’ ‘WELCOME TO THE CLUB’ NYMPHS -’S/T’ RTZ - ‘RETURN TO ZERO’ WARTHCHILD AMERICA GIRL - ‘SHEER GREED’ GIRL - ‘WASTED YOUTH’ LOVE/HATE ‘CLIMBIN’ THE WALLS’ ‘BLACKOUT IN THE RED ROOM’ MAIDEN ‘84 BEHIND THE SCENES ON THE LEGENDARY POLAND TOUR TARGET - ‘S/T’ TARGET - ‘CAPTURED’ MAYDAY - ‘S/T’ MAYDAY - ‘REVENGE’ BAD BOY - ‘THE BAND THAT BAD BOY - ‘BACK TO BACK’ MILWAUKEE MADE FAMOUS’ COMING SOON BAD ENGLISH - ‘S/T’ JETBOY - ‘FEEL THE SHAKE’ DOKKEN STONE FURY ALANNAH MILES - ‘S/T’ ‘BEAST FROM THE EAST’ ‘BURNS LIKE A STAR’ www.rockcandyrecords.com / [email protected] -

Rdr 360 Classics Manual

WARNING Before playing this game, read the Xbox 360® console, Xbox 360 Kinect® Sensor, and accessory manuals for important safety and health information. www.xbox.com/support. Important Health Warning: Photosensitive Seizures A very small percentage of people may experience a seizure when exposed to certain visual images, including flashing lights or patterns that may appear in video games. Even people with no history of seizures or epilepsy may have an undiagnosed condition that can cause “photosensitive epileptic seizures” while watching video games. Symptoms can include light-headedness, altered vision, eye or face twitching, jerking or shaking of arms or legs, disorientation, confusion, momentary loss of awareness, and loss of consciousness or convulsions that can lead to injury from falling down or striking nearby objects. Immediately stop playing and consult a doctor if you experience any of these symptoms. Parents, watch for or ask children about these symptoms—children and teenagers are more likely to experience these seizures. The risk may be reduced by being farther from the screen; using a smaller screen; playing in a well-lit room, and not playing when drowsy or fatigued. If you or any relatives have a history of seizures or epilepsy, consult a doctor before playing. STORY Game Controls ..................02 JOHN MARSTON WAS A FORMER GANG HEADS UP DISPLAY................04 MEMBER WHO REAPPRAISED HIS LIFE MULTIPLAYER ......................06 and resolved to put his past behind him to settle down with his young TRAVEL ...............................09 family. As Marston changed, so JOURNAL ............................. 10 did the landscape. The federal government set its sights on bringing FAME AND Honour ..................11 their law to the whole country by any LAW ENFORCEMENT ............. -

1 in the United States District

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF PENNSYLVANIA DAVID HOLT II, : CIVIL ACTION Plaintiff, : : v. : : COMMONWEALTH OF : NO. 10-5510 PENNSYLVANIA, et al., : Defendants. : MEMORANDUM OPINION DAVID R. STRAWBRIDGE UNITED STATES MAGISTRATE JUDGE August 19, 2015 David Holt II (alternately “Holt” or “Plaintiff”), an African American male and a Pennsylvania State Police (“PSP”) Sergeant, filed this action against the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the PSP, retired Captain Steven Johnson (“Johnson”), retired Lieutenant Gerald Brahl (“Brahl”), retired Captain Kathy Jo Winterbottom (“Winterbottom”), and Lieutenant Kristal Turner–Childs (“Turner-Childs”); (collectively the “Defendants”). Through this lawsuit, he raised Fourteenth Amendment equal protection and First Amendment retaliation claims against the individual Defendants under 42 U.S.C. § 1983 (“Section 1983”). He also brought aiding and abetting discrimination and retaliation claims against the individual defendants under the Pennsylvania Human Relations Act, 43 Pa. Cons. Stat. § 951, et seq. (“PHRA”), and discrimination and retaliation claims against the PSP under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e, et seq., (“Title VII”). The case was initially tried before a jury in October and November of 2013. Following Defendants’ Fed. R. Civ. P. 50(a) motion, we entered judgment in favor of Turner-Childs and dismissed her from the case. We also granted 1 judgment as a matter of law under Fed. R. Civ. P. 50(a) in favor of Winterbottom and Brahl on the PHRA claims and in favor of the PSP on the Title VII claims, as they concerned the acts of those two officers. The remaining claims under Title VII and the PHRA against the PSP and Johnson and under Section 1983 equal protection and retaliation against Brahl and Winterbottom were presented to the jury. -

THE LINCOLN ECHO Fort Smith, AR PERMIT#240

PRESORTED STANDARD U.S. POSTAGE PAID THE LINCOLN ECHO Fort Smith, AR PERMIT#240 We Report the NEWS. You Interpret It. Website www.thelincolnecho.com MARCH 2014 Volume 23 Issue 12 P.O. BOX 771 Fort Smith, Arkansas 72902 50 CENTS ADAM WEBSTER HONORED Baridi Nkokheli, City of Fort Smith director of sanitation, conducts a Bass Reeves presentation at a Black History Month event held at The Fort Smith Noon Exchange Club honored another the 188th Fighter Wing headquarters auditorium Feb. 9, 2014. Be- outstanding volunteer at their 72nd Annual Golden Deeds cause of his resemblance to the former U.S. Marshal and Van Buren, Banquet on February 7, at Fianna Hills Country Club. Ark., native Reeves, Nkokheli often re-enacts the character of Reeves The Book of Golden Deeds Award, recognizes dedicated in presentations around the area. volunteers who give endless hours of their time and talents Baridi is also very active in community activities giving youth the toward making their communities better places to live. opportunity to make positive contributions to their development. The 2013 Golden Deeds recipient honored at the Golden Deeds Banquet was Adam Webster. Adam has been a volunteer football coach at the Fort Smith Boys & Girls Club for the past 40 years. During the past 36 consecutive seasons, he has coached the McDonalds midget league team at the Evans Boys & Girls Club. One of his former players at the club, Gus Malzahn, was recently awarded the Fort Smith Boys & Girls Club with a $20,000 cash award. This gift was presented to the Club on behalf of Coach Malzahn and Liberty Mutual. -

Alues Are Forcing German Retreat

VOL LVII.-- NO. Ill rtWieH, CONNj TUEIDAY MAY llj J91S TEN PAGE3 PRICE TWO CENTS The Bulletin's Circulation in Norwich is Double That o y Other Paper, and Its Total Circulation Is the Largest In Connecticut in Proportion to the City's Population Cu Paragraphs Lusitania Deaths Germany Regrets Condensed Telegrams Course United ALUES ARE FORCING Geven More Bodies Pound, ' Prisoner In Bins Sing prison crowd- Cork, May XI. 8,03 a. m, Seven ed the prison auditorium to hear bodies frem the Ltislt&nia were Henry Ford fepg&k. landed at Baltimore last evening from Wilful Murder Lossof Americans States Will Pursue a patrol beat, One million persons are expected to visit tbe Atlantis fleet during lta ten-da- y Japanese Cruiser Refloated. stay at New York. GERMAN RETREAT Toklo, May 10. The Japanese ACCORDING TO VERDICT RE- DESPATCH RECEIVED PROM FOR- INTIMATED BY PRESIDENT IB cruleer Asama, which ran ashore on Italy will begin restrictions on the the coast of Lower California on Feb- TURNED BY CORONER'S JURY. EIGN OFFICE. Importations of cotton from ship- PHILADELPHIA SPEECH. ruary 4, has been accordi- ments leaving foreign porta on May ng1 to official announcement made 10. here. The Asama will probably be docked TO REMAIN AT PEACE A Strong Movement Made Against the Enemy With and repaired at San Francisco. AN APPALLING CRIME ACT OF RETALIATION Fifty Inmates of the Connecticut re- formatory, taken from the first grade, Or. DoPage Identifies Body of His were out to work at road building Wife. Heavy Reinforcements Contrary to International Law Against British Government for Plao-in- g yesterday But Seek to Convince Germany Thai Queenstown, May 10. -

Ellsworth American, a Newspaper Action Creating Is No Excuse for Tbe Both Kinds of Expenditures for Indigent Per- Large Plain Deceased

Cl)e CUstoorfl) American* l\ ii. IVS™ T*“1 ELLSWORTH, Wednesday jjou. Maine, afternoon, December 13,1911. 1 t,» ajt”;( no. so. HVHHMBCMIHIig, | LOCAL AFFAIRS. lain, Laura Curtis; conductor, Minnie &bbrrtttmmta. Stevens; guard, Mary Jordan; delegate, Nellie NEW ADVERTISEMENTS THI8 WEEK. Royal; alternate, Minnie Stevens. The N.rrT 0 Aa.tln A Co—Furniture end under- kindergarten class of the Methodist taking. Sunday school is having a sale of home- E G Moore—Druggist. made and Are You Ellsworth Foundry & Machine Works-Au- candy fancy articles in the Hesitating tomobiles. Methodist vestry this afternoon. A UNION TRUST Ellsworth Greenhouse. COMPANY chicken Monaghan’s dancing school. supper will be served at 6 o’clock, A I f OF ELLSWORTH have hundreds of who will vouch for Richardson—Closiug-out sale. followed by a social. I \\rE patrons Probate notice—Frank P Wood, et ale. Franklin: Acadia Royal Arch chapter will hold a our accu the which wo afford * acy, security, deposit- C E Dwelley—Notice. special meeting next Tuesday evening, OFFICERS John A. ors, and tl> completeness of the services we per- Pbnorscot: when Deputy Grand High Priest Charles Peters, President Hbnby W. Cushman, Vi$e* President Benny U. Treasurer f foi th m. Non-resident tax notice. B. Davis, of Watervilie, will pay his offi- Higgins, M. Oaixekt, '1 righaij form Sorrbnto: cial visit. Supper will be served at 8.30. Non-resident tax If we render valuable service to notice. There will be work in the R. A. DIRECTORS others, why Bucksport: degree. John of not to you? Bucksport NRt’l Bank—Statement.