The Value of Youth in Major League Baseball

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tigers Make Big Trade, White Sox Win Game 7-4

SPORTS SATURDAY, AUGUST 2, 2014 Tigers make big trade, White Sox win game 7-4 Los Angeles avert three-game series sweep DETROIT: Moises Sierra had four hits, and Jose of last-place teams. The Rockies have lost four of Abreu and Adam Eaton added three apiece to lift five and 11 of 15 overall. Pedro Hernandez (0-1) the Chicago White Sox to a 7-4 victory over the allowed three runs and six hits in 5 2-3 innings in Detroit Tigers on Thursday. The game quickly his first start for Colorado. became a secondary concern in the Motor City Hector Rondon got three outs for his 14th save when the Tigers acquired star left-hander David in 17 opportunities. He retired three straight after Price from Tampa Bay in a three-team deal. Joakim Nolan Arenado and Justin Morneau singled to start Soria (1-4) - another pitcher recently acquired by the ninth. The Cubs made one trade on the non- Detroit - hit Paul Konerko with the bases loaded in waiver deadline day, sending utilityman Emilio the seventh to give the White Sox a 5-4 lead. Abreu Bonifacio, reliever James Russell and cash to extended his hitting streak to 20 games. Ronald Atlanta for catching prospect Victor Caratini. Belisario (4-7) got the win in relief, and Jake Petricka pitched the ninth for his sixth save. BLUE JAYS 6, ASTROS 5 Detroit’s Torii Hunter and JD Martinez hit back-to- Nolan Reimold hit two home runs, including a back homers in the third. tiebreaking solo shot in the ninth, and Toronto ral- lied for a win. -

Administration of Barack Obama, 2011 Remarks Honoring the 2010 World

Administration of Barack Obama, 2011 Remarks Honoring the 2010 World Series Champion San Francisco Giants July 25, 2011 The President. Well, hello, everybody. Have a seat, have a seat. This is a party. Welcome to the White House, and congratulations to the Giants on winning your first World Series title in 56 years. Give that a big round. I want to start by recognizing some very proud Giants fans in the house. We've got Mayor Ed Lee; Lieutenant Governor Gavin Newsom. We have quite a few Members of Congress—I am going to announce one; the Democratic Leader in the House, Nancy Pelosi is here. We've got Senator Dianne Feinstein who is here. And our newest Secretary of Defense and a big Giants fan, Leon Panetta is in the house. I also want to congratulate Bill Neukom and Larry Baer for building such an extraordinary franchise. I want to welcome obviously our very special guest, the "Say Hey Kid," Mr. Willie Mays is in the house. Now, 2 years ago, I invited Willie to ride with me on Air Force One on the way to the All-Star Game in St. Louis. It was an extraordinary trip. Very rarely when I'm on Air Force One am I the second most important guy on there. [Laughter] Everybody was just passing me by—"Can I get you something, Mr. Mays?" [Laughter] What's going on? Willie was also a 23-year-old outfielder the last time the Giants won the World Series, back when the team was in New York. -

Greetings! for the 13,000 Students in Our Programs Nationwide, the Start of Fall Is About More Than Going Back to School. for Ma

Greetings! For the 13,000 students in our programs nationwide, the start of fall is about more than going back to school. For many, it’s the opportunity to reconnect with our counselors and our safe rooms. From preparing for our Domestic Violence Awareness Month campaigns, to partnering with baseball teams (both minor AND major), to celebrating a big milestone, we have so much to share with you. Check out some highlights from Safe At Home! Sneak Peak: DV Awareness Month Planning Every October, Safe At Home commemorates Domestic Violence Awareness Month by holding school-wide awareness campaigns at all of our 15 locations. A group of students – known as peer leaders – will work with the therapist to spread the word throughout their school, using skills like leadership and advocacy that they’ll continue to build throughout the year. This year’s theme is all about those skills, and more. “Your words are your power. How will you use yours?” will encourage students to look to the strengths and power they already possess to be an ally and advocate. We look forward to sharing stories about their campaign activities soon, but in the meantime, check out this beautiful campaign poster made by Safe At Home’s alumni intern, Julissa. Did you know that a gift of just $250 can help us buy the supplies we need for an awareness campaign for one entire school? Visit joetorre.org/donate to make a gift of any size to support our awareness campaigns. Partnership with Minor League Baseball Raises $5000+ Safe At Home partnered with Minor League Baseball for our third annual Domestic Violence Awareness Night campaign this summer. -

Believe: the Story of the 2005 Chicago White Sox" by David J

Believe: The Story of the 2005 Chicago White Sox" By David J. Fletcher, CBM President Posted Sunday, April 12, 2015 Disheartened White Sox fans, who are disappointed by the White Sox slow start in 2015, can find solace in Sunday night’s television premiere of “Believe: The Story of the 2005 Chicago White Sox" that airs on Sunday night April 12th at 7pm on Comcast Sports Net Chicago. Produced by the dynamic CSN Chi- cago team of Sarah Lauch and Ryan Believe: The Story of the 2005 Chicago White Sox will air McGuffey, "Believe" is an emotional on Sunday, Apr. 12 at 7:00pm CT, on Comcast Sportsnet. roller-coaster-ride of a look at a key season in Chicago baseball history that even the casual baseball fan will enjoy because of the story—a star-crossed team cursed by the 1919 Black Sox—erases 88 years of failure and wins the 2005 World Series championship. Lauch and McGuffey deliver an extraordinary historical documentary that includes fresh interviews with all the key participants, except pitcher Mark Buehrle who declined. “Mark respectfully declined multiple interview requests. (He) wanted the focus to be on his current season,” said McGuffey. Lauch did reveal “that Buehrle’s wife saw the film trailer on the Thursday (April 9th) and loved it.” Primetime Emmy & Tony Award winner, current star of Showtime’s acclaimed drama series “Homeland”, and lifelong White Sox fan Mandy Patinkin, narrates the film in an under-stated fashion that retains a hint of his Southside roots and loyalties. The 76 minute-long “Believe” features all of the signature -

Alltime Baseball Champions

ALLTIME BASEBALL CHAMPIONS MAJOR DIVISION Year Champion Head Coach Score Runnerup Site 1914 Orange William Fishback 8 4 Long Beach Poly Occidental College 1915 Hollywood Charles Webster 5 4 Norwalk Harvard Military Academy 1916 Pomona Clint Evans 87 Whittier Pomona HS 1917 San Diego Clarence Price 122 Norwalk Manual Arts HS 1918 San Diego Clarence Price 102 Huntington Park Manual Arts HS 1919 Fullerton L.O. Culp 119 Pasadena Tournament Park, Pasadena 1920 San Diego Ario Schaffer 52 Glendale San Diego HS 1921 San Diego John Perry 145 Los Angeles Lincoln Alhambra HS 1922 Franklin Francis L. Daugherty 10 Pomona Occidental College 1923 San Diego John Perry 121 Covina Fullerton HS 1924 Riverside Ashel Cunningham 63 El Monte Riverside HS 1925 San Bernardino M.P. Renfro 32 Fullerton Fullerton HS 1926 Fullerton 138 Santa Barbara Santa Barbara 1927 Fullerton Stewart Smith 9 0 Alhambra Fullerton HS 1928 San Diego Mike Morrow 30 El Monte El Monte HS 1929 San Diego Mike Morrow 41 Fullerton San Diego HS 1930 San Diego Mike Morrow 80 Cathedral San Diego HS 1931 Colton Norman Frawley 43 Citrus Colton HS 1932 San Diego Mikerow 147 Colton San Diego HS 1933 Santa Maria Kit Carlson 91 San Diego Hoover San Diego HS 1934 Cathedral Myles Regan 63 San Diego Hoover Wrigley Field, Los Angeles 1935 San Diego Mike Morrow 82 Santa Maria San Diego HS 1936 Long Beach Poly Lyle Kinnear 144 Escondido Burcham Field, Long Beach 1937 San Diego Mike Morrow 168 Excelsior San Diego HS 1938 Glendale George Sperry 6 0 Compton Wrigley Field, Los Angeles 1939 San Diego Mike Morrow 30 Long Beach Wilson San Diego HS 1940 Long Beach Wilson Fred Johnson Default (San Diego withdrew) 1941 Santa Barbara Skip W. -

2011 Topps Gypsy Queen Baseball

Hobby 2011 TOPPS GYPSY QUEEN BASEBALL Base Cards 1 Ichiro Suzuki 49 Honus Wagner 97 Stan Musial 2 Roy Halladay 50 Al Kaline 98 Aroldis Chapman 3 Cole Hamels 51 Alex Rodriguez 99 Ozzie Smith 4 Jackie Robinson 52 Carlos Santana 100 Nolan Ryan 5 Tris Speaker 53 Jimmie Foxx 101 Ricky Nolasco 6 Frank Robinson 54 Frank Thomas 102 David Freese 7 Jim Palmer 55 Evan Longoria 103 Clayton Richard 8 Troy Tulowitzki 56 Mat Latos 104 Jorge Posada 9 Scott Rolen 57 David Ortiz 105 Magglio Ordonez 10 Jason Heyward 58 Dale Murphy 106 Lucas Duda 11 Zack Greinke 59 Duke Snider 107 Chris V. Carter 12 Ryan Howard 60 Rogers Hornsby 108 Ben Revere 13 Joey Votto 61 Robin Yount 109 Fred Lewis 14 Brooks Robinson 62 Red Schoendienst 110 Brian Wilson 15 Matt Kemp 63 Jimmie Foxx 111 Peter Bourjos 16 Chris Carpenter 64 Josh Hamilton 112 Coco Crisp 17 Mark Teixeira 65 Babe Ruth 113 Yuniesky Betancourt 18 Christy Mathewson 66 Madison Bumgarner 114 Brett Wallace 19 Jon Lester 67 Dave Winfield 115 Chris Volstad 20 Andre Dawson 68 Gary Carter 116 Todd Helton 21 David Wright 69 Kevin Youkilis 117 Andrew Romine 22 Barry Larkin 70 Rogers Hornsby 118 Jason Bay 23 Johnny Cueto 71 CC Sabathia 119 Danny Espinosa 24 Chipper Jones 72 Justin Morneau 120 Carlos Zambrano 25 Mel Ott 73 Carl Yastrzemski 121 Jose Bautista 26 Adrian Gonzalez 74 Tom Seaver 122 Chris Coghlan 27 Roy Oswalt 75 Albert Pujols 123 Skip Schumaker 28 Tony Gwynn Sr. 76 Felix Hernandez 124 Jeremy Jeffress 2929 TTyy Cobb 77 HHunterunter PPenceence 121255 JaJakeke PPeavyeavy 30 Hanley Ramirez 78 Ryne Sandberg 126 Dallas -

Trevor Bauer

TREVOR BAUER’S CAREER APPEARANCES Trevor Bauer (47) 2009 – Freshman (9-3, 2.99 ERA, 20 games, 10 starts) JUNIOR – RHP – 6-2, 185 – R/R Date Opponent IP H R ER BB SO W/L SV ERA Valencia, Calif. (Hart HS) 2/21 UC Davis* 1.0 0 0 0 0 2 --- 1 0.00 2/22 UC Davis* 4.1 7 3 3 2 6 L 0 5.06 CAREER ACCOLADES 2/27 vs. Rice* 2.2 3 2 1 4 3 L 0 4.50 • 2011 National Player of the Year, Collegiate Baseball • 2011 Pac-10 Pitcher of the Year 3/1 UC Irvine* 2.1 1 0 0 0 0 --- 0 3.48 • 2011, 2010, 2009 All-Pac-10 selection 3/3 Pepperdine* 1.1 1 1 1 1 2 L 0 3.86 • 2010 Baseball America All-America (second team) 3/7 at Oklahoma* 0.2 1 0 0 0 0 --- 0 3.65 • 2010 Collegiate Baseball All-America (second team) 3/11 San Diego State 6.0 2 1 1 3 4 --- 0 2.95 • 2009 Louisville Slugger Freshman Pitcher of the Year 3/11 at East Carolina* 3.2 2 0 0 0 5 W 0 2.45 • 2009 Collegiate Baseball Freshman All-America 3/21 at USC* 4.0 4 2 1 0 3 --- 1 2.42 • 2009 NCBWA Freshman All-America (first team) 3/25 at Pepperdine 8.0 6 2 2 1 8 W 0 2.38 • 2009 Pac-10 Freshman of the Year 3/29 Arizona* 5.1 4 0 0 1 4 W 0 2.06 • Posted a 34-8 career record (32-5 as a starter) 4/3 at Washington State* 0.1 1 2 1 0 0 --- 0 2.27 • 1st on UCLA’s career strikeouts list (460) 4/5 at Washington State 6.2 9 4 4 0 7 W 0 2.72 • 1st on UCLA’s career wins list (34) 4/10 at Stanford 6.0 8 5 4 0 5 W 0 3.10 • 1st on UCLA’s career innings list (373.1) 4/18 Washington 9.0 1 0 0 2 9 W 0 2.64 • 2nd on Pac-10’s career strikeouts list (460) 4/25 Oregon State 8.0 7 2 2 1 7 W 0 2.60 • 2nd on UCLA’s career complete games list (15) 5/2 at Oregon 9.0 6 2 2 4 4 W 0 2.53 • 8th on UCLA’s career ERA list (2.36) • 1st on Pac-10’s single-season strikeouts list (203 in 2011) 5/9 California 9.0 8 4 4 1 10 W 0 2.68 • 8th on Pac-10’s single-season strikeouts list (165 in 2010) 5/16 Cal State Fullerton 9.0 8 5 5 2 8 --- 0 2.90 • 1st on UCLA’s single-season strikeouts list (203 in 2011) 5/23 at Arizona State 9.0 6 4 4 5 5 W 0 2.99 • 2nd on UCLA’s single-season strikeouts list (165 in 2010) TOTAL 20 app. -

Baseball Classics All-Time All-Star Greats Game Team Roster

BASEBALL CLASSICS® ALL-TIME ALL-STAR GREATS GAME TEAM ROSTER Baseball Classics has carefully analyzed and selected the top 400 Major League Baseball players voted to the All-Star team since it's inception in 1933. Incredibly, a total of 20 Cy Young or MVP winners were not voted to the All-Star team, but Baseball Classics included them in this amazing set for you to play. This rare collection of hand-selected superstars player cards are from the finest All-Star season to battle head-to-head across eras featuring 249 position players and 151 pitchers spanning 1933 to 2018! Enjoy endless hours of next generation MLB board game play managing these legendary ballplayers with color-coded player ratings based on years of time-tested algorithms to ensure they perform as they did in their careers. Enjoy Fast, Easy, & Statistically Accurate Baseball Classics next generation game play! Top 400 MLB All-Time All-Star Greats 1933 to present! Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player 1933 Cincinnati Reds Chick Hafey 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Mort Cooper 1957 Milwaukee Braves Warren Spahn 1969 New York Mets Cleon Jones 1933 New York Giants Carl Hubbell 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Enos Slaughter 1957 Washington Senators Roy Sievers 1969 Oakland Athletics Reggie Jackson 1933 New York Yankees Babe Ruth 1943 New York Yankees Spud Chandler 1958 Boston Red Sox Jackie Jensen 1969 Pittsburgh Pirates Matty Alou 1933 New York Yankees Tony Lazzeri 1944 Boston Red Sox Bobby Doerr 1958 Chicago Cubs Ernie Banks 1969 San Francisco Giants Willie McCovey 1933 Philadelphia Athletics Jimmie Foxx 1944 St. -

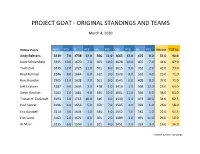

Project Goat - Original Standings and Teams

PROJECT GOAT - ORIGINAL STANDINGS AND TEAMS March 4, 2020 Hitting Points AVG PTS R PTS HR PTS RBI PTS SB PTS Hitting TOTAL Andy Behrens .3219 7.0 1738 12.0 566 11.0 1665 12.0 425 9.0 51.0 94.0 Dave Schoenfield .3295 10.0 1670 7.0 563 10.0 1628 10.0 407 7.0 44.0 87.0 Todd Zola .3339 12.0 1725 11.0 551 8.0 1615 9.0 352 2.0 42.0 73.0 Brad Kullman .3246 8.0 1664 6.0 512 3.0 1579 8.0 362 4.0 29.0 71.0 Ron Shandler .3305 11.0 1628 3.0 561 9.0 1545 6.0 408 8.0 37.0 71.0 Jeff Erickson .3287 9.0 1605 2.0 478 1.0 1410 1.0 508 12.0 25.0 63.0 Steve Gardner .3161 1.0 1681 9.0 596 12.0 1661 11.0 366 5.0 38.0 63.0 Tristan H. Cockcroft .3193 3.0 1713 10.0 546 6.0 1530 5.0 473 10.0 34.0 62.5 Paul Sporer .3196 4.0 1653 5.0 550 7.0 1505 4.0 392 6.0 26.0 58.0 Eric Karabell .3214 5.0 1644 4.0 543 5.0 1552 7.0 342 1.0 22.0 51.5 Eno Sarris .3163 2.0 1671 8.0 504 2.0 1489 3.0 491 11.0 26.0 50.0 AJ Mass .3215 6.0 1599 1.0 521 4.0 1451 2.0 353 3.0 16.0 36.0 *Sorted by final standings Pitching Points W PTS SV PTS K PTS ERA PTS WHIP PTS Pitching TOTAL Andy Behrens 187 11.5 0 1.5 2348 12.0 1.98 9.0 0.90 9.0 43.0 94.0 Dave Schoenfield 187 11.5 0 1.5 2288 11.0 1.95 11.0 0.91 8.0 43.0 87.0 Todd Zola 150 7.0 104 4.0 2154 8.0 2.03 7.0 0.95 5.0 31.0 73.0 Brad Kullman 141 4.5 141 10.5 1941 3.0 1.84 12.0 0.90 12.0 42.0 71.0 Ron Shandler 141 4.5 141 10.5 1886 2.0 1.97 10.0 0.93 7.0 34.0 71.0 Jeff Erickson 151 8.0 112 6.0 2130 6.0 2.01 8.0 0.90 10.0 38.0 63.0 Steve Gardner 147 6.0 105 5.0 2152 7.0 2.06 5.0 0.98 2.0 25.0 63.0 Tristan H. -

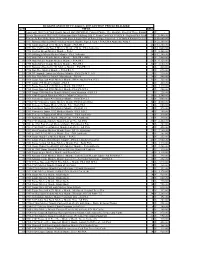

PDF of August 17 Results

HUGGINS AND SCOTT'S August 3, 2017 AUCTION PRICES REALIZED LOT# TITLE BIDS 1 Landmark 1888 New York Giants Joseph Hall IMPERIAL Cabinet Photo - The Absolute Finest of Three Known Examples6 $ [reserve - not met] 2 Newly Discovered 1887 N693 Kalamazoo Bats Pittsburg B.B.C. Team Card PSA VG-EX 4 - Highest PSA Graded &20 One$ 26,400.00of Only Four Known Examples! 3 Extremely Rare Babe Ruth 1939-1943 Signed Sepia Hall of Fame Plaque Postcard - 1 of Only 4 Known! [reserve met]7 $ 60,000.00 4 1951 Bowman Baseball #253 Mickey Mantle Rookie Signed Card – PSA/DNA Authentic Auto 9 57 $ 22,200.00 5 1952 Topps Baseball #311 Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 40 $ 12,300.00 6 1952 Star-Cal Decals Type I Mickey Mantle #70-G - PSA Authentic 33 $ 11,640.00 7 1952 Tip Top Bread Mickey Mantle - PSA 1 28 $ 8,400.00 8 1953-54 Briggs Meats Mickey Mantle - PSA Authentic 24 $ 12,300.00 9 1953 Stahl-Meyer Franks Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 (MK) 29 $ 3,480.00 10 1954 Stahl-Meyer Franks Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 58 $ 9,120.00 11 1955 Stahl-Meyer Franks Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 20 $ 3,600.00 12 1952 Bowman Baseball #101 Mickey Mantle - PSA FR 1.5 6 $ 480.00 13 1954 Dan Dee Mickey Mantle - PSA FR 1.5 15 $ 690.00 14 1954 NY Journal-American Mickey Mantle - PSA EX-MT+ 6.5 19 $ 930.00 15 1958 Yoo-Hoo Mickey Mantle Matchbook - PSA 4 18 $ 840.00 16 1956 Topps Baseball #135 Mickey Mantle (White Back) PSA VG 3 11 $ 360.00 17 1957 Topps #95 Mickey Mantle - PSA 5 6 $ 420.00 18 1958 Topps Baseball #150 Mickey Mantle PSA NM 7 19 $ 1,140.00 19 1968 Topps Baseball #280 Mickey Mantle PSA EX-MT -

The Role of Skill Versus Luck in Poker: Evidence from the World Series of Poker

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES THE ROLE OF SKILL VERSUS LUCK IN POKER: EVIDENCE FROM THE WORLD SERIES OF POKER Steven D. Levitt Thomas J. Miles Working Paper 17023 http://www.nber.org/papers/w17023 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 May 2011 We would like to thank Carter Mundell for truly outstanding research assistance. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2011 by Steven D. Levitt and Thomas J. Miles. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. The Role of Skill Versus Luck in Poker: Evidence from the World Series of Poker Steven D. Levitt and Thomas J. Miles NBER Working Paper No. 17023 May 2011 JEL No. K23,K42 ABSTRACT In determining the legality of online poker – a multibillion dollar industry – courts have relied heavily on the issue of whether or not poker is a game of skill. Using newly available data, we analyze that question by examining the performance in the 2010 World Series of Poker of a group of poker players identified as being highly skilled prior to the start of the events. Those players identified a priori as being highly skilled achieved an average return on investment of over 30 percent, compared to a -15 percent for all other players. -

2010 Topps Baseball Set Checklist

2010 TOPPS BASEBALL SET CHECKLIST 1 Prince Fielder 2 Buster Posey RC 3 Derrek Lee 4 Hanley Ramirez / Pablo Sandoval / Albert Pujols LL 5 Texas Rangers TC 6 Chicago White Sox FH 7 Mickey Mantle 8 Joe Mauer / Ichiro / Derek Jeter LL 9 Tim Lincecum NL CY 10 Clayton Kershaw 11 Orlando Cabrera 12 Doug Davis 13 Melvin Mora 14 Ted Lilly 15 Bobby Abreu 16 Johnny Cueto 17 Dexter Fowler 18 Tim Stauffer 19 Felipe Lopez 20 Tommy Hanson 21 Cristian Guzman 22 Anthony Swarzak 23 Shane Victorino 24 John Maine 25 Adam Jones 26 Zach Duke 27 Lance Berkman / Mike Hampton CC 28 Jonathan Sanchez 29 Aubrey Huff 30 Victor Martinez 31 Jason Grilli 32 Cincinnati Reds TC 33 Adam Moore RC 34 Michael Dunn RC 35 Rick Porcello 36 Tobi Stoner RC 37 Garret Anderson 38 Houston Astros TC 39 Jeff Baker 40 Josh Johnson 41 Los Angeles Dodgers FH 42 Prince Fielder / Ryan Howard / Albert Pujols LL Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© 2019 1 43 Marco Scutaro 44 Howie Kendrick 45 David Hernandez 46 Chad Tracy 47 Brad Penny 48 Joey Votto 49 Jorge De La Rosa 50 Zack Greinke 51 Eric Young Jr 52 Billy Butler 53 Craig Counsell 54 John Lackey 55 Manny Ramirez 56 Andy Pettitte 57 CC Sabathia 58 Kyle Blanks 59 Kevin Gregg 60 David Wright 61 Skip Schumaker 62 Kevin Millwood 63 Josh Bard 64 Drew Stubbs RC 65 Nick Swisher 66 Kyle Phillips RC 67 Matt LaPorta 68 Brandon Inge 69 Kansas City Royals TC 70 Cole Hamels 71 Mike Hampton 72 Milwaukee Brewers FH 73 Adam Wainwright / Chris Carpenter / Jorge De La Ro LL 74 Casey Blake 75 Adrian Gonzalez 76 Joe Saunders 77 Kenshin Kawakami 78 Cesar Izturis 79 Francisco Cordero 80 Tim Lincecum 81 Ryan Theroit 82 Jason Marquis 83 Mark Teahen 84 Nate Robertson 85 Ken Griffey, Jr.