Hurricane Andres Tropical Cyclone Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Climatology, Variability, and Return Periods of Tropical Cyclone Strikes in the Northeastern and Central Pacific Ab Sins Nicholas S

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School March 2019 Climatology, Variability, and Return Periods of Tropical Cyclone Strikes in the Northeastern and Central Pacific aB sins Nicholas S. Grondin Louisiana State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Climate Commons, Meteorology Commons, and the Physical and Environmental Geography Commons Recommended Citation Grondin, Nicholas S., "Climatology, Variability, and Return Periods of Tropical Cyclone Strikes in the Northeastern and Central Pacific asinB s" (2019). LSU Master's Theses. 4864. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/4864 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CLIMATOLOGY, VARIABILITY, AND RETURN PERIODS OF TROPICAL CYCLONE STRIKES IN THE NORTHEASTERN AND CENTRAL PACIFIC BASINS A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in The Department of Geography and Anthropology by Nicholas S. Grondin B.S. Meteorology, University of South Alabama, 2016 May 2019 Dedication This thesis is dedicated to my family, especially mom, Mim and Pop, for their love and encouragement every step of the way. This thesis is dedicated to my friends and fraternity brothers, especially Dillon, Sarah, Clay, and Courtney, for their friendship and support. This thesis is dedicated to all of my teachers and college professors, especially Mrs. -

WMO Statement on the Status of the Global Climate in 2009

WMO statement on the status of the global climate in 2009 WMO-No. 1055 WMO-No. 1055 © World Meteorological Organization, 2010 The right of publication in print, electronic and any other form and in any language is reserved by WMO. Short extracts from WMO publications may be reproduced without authorization, provided that the complete source is clearly indicated. Editorial correspondence and requests to publish, reproduce or translate this publication in part or in whole should be addressed to: Chair, Publications Board World Meteorological Organization (WMO) 7 bis, avenue de la Paix Tel.: +41 (0) 22 730 84 03 P.O. Box 2300 Fax: +41 (0) 22 730 80 40 CH-1211 Geneva 2, Switzerland E-mail: [email protected] ISBN 978-92-63-11055-8 WMO in collaboration with Members issues since 1993 annual statements on the status of the global climate. This publication was issued in collaboration with the Hadley Centre of the UK Meteorological Office and the Climatic Research Unit, University of East Anglia, United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland; and the National Climatic Data Center, the National Environmental Satellite, Data, and Information Service, and the National Weather Service of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the Goddard Institute for Space Studies operated by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), and the National Snow and Ice Data Center, United States of America. Other contributors are the National Meteorological and Hydrological Services of Algeria, Argentina, Australia, Brazil, -

Border Climate Summary

%RUGHU&OLPDWH6XPPDU\ 5HVXPHQGHO&OLPDGHOD)URQWHUD ,VVXHG)HEUXDU\ Tree Rings and the Monsoon in the Southwestern U.S. B" D#$%&' G(%))%$, S*+,,' ,) G&- To better grasp ,-(#.+" #$/ D&0&',.1&$2 #$/ T+& the full range of L#3,(#2,(" ,) T(&&-R%$- R&4&#(*+, spatial and tem- U$%0&(4%2" ,) A(%5,$# poral variabil- ity that is pos- 6e monsoon is a major component of sible under natu- southwestern North America’s climate ral (non-human) regime and arguably one of the most conditions, re- anticipated regional climate events of searchers at the the year, delivering varying doses of life- University of Ar- giving rains to the U.S.-Mexico border re- izona are study- (: /: (: /: (: (: /: gion each summer. On average, the mon- ing the long- Dry Dry Dry soon brings three-fourths of northwestern term climate Wet Wet Wet Wet Winter Winter Winter Winter Mexico’s annual rainfall and up to half of history of the Summer Summer Summer Pre-Monson? Pre-Monsoon? the annual rain in the U.S. Southwest. monsoon using Dry Summer annual growth Figure 1. This photomicrograph illustrates a sequence of four Douglas- !r tree rings (1871–1874) from southwestern New Mexico. Each annual Variability in monsoon rainfall in time rings from long- growth ring is composed of light-colored earlywood (EW) and dark-colored and location increases northward with lived, moisture- latewood (LW). Both 1871 and 1872 contain intra-annual density variations distance from the “core region” in west- stressed trees. known as “false rings,” which are probably related to reduced soil moisture ern and northwestern Mexico and is in the May–June pre-monsoon period. -

Tropical Cyclone Characterization Via Nocturnal Low-Light Visible Illumination

TROPICAL CYCLONE CHARACTERIZATION VIA NOCTURNAL LOW-LIGHT VISIBLE ILLUMINATION JEFFREY D. HAWKINS, JEREMY E. SOlbRIG, STEVEN D. MIllER, MELINDA SURRATT, THOMAS F. LEE, RICHARD L. BANKERT, AND KIM RICHARDSON Nighttime visible digital data from the Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) have the potential to complement the current infrared imagery standard-bearer in monitoring global tropical cyclone characteristics. he Suomi National Polar-Orbiting Partnership (IR) passive radiometer, whose special ability to sense (SNPP) satellite was launched on 28 October 2011 extremely low levels of light in the 500–900-nm T and placed into a sun-synchronous afternoon bandpass provides a unique opportunity to exploit polar orbit (1330 local time ascending node with a nighttime visible signals for nighttime environmental corresponding nocturnal 0130 local time descending characterization (Lee et al. 2006; Miller et al. 2013). The node). SNPP carries a day–night band (DNB) sensor as improved capabilities hold potentially high relevance to part of the Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite the nocturnal monitoring and characterization of tropi- (VIIRS). The DNB is a visible (VIS)–near-infrared cal cyclones (TC) within the world’s oceanic basins. Accurately detecting TC structure (rainband organization, eyewall characterization, surface cir- a a culation center location, and intensity) in near–real AFFILIATIONS: HAWKINS, SURRATT, LEE, BANKERT, AND RICHARDSON—Naval Research Laboratory, Marine Meteorology time typically is problematic owing to 1) a scarcity Division, Monterey, California; SOlbRIG AND MIllER—Cooperative of in situ observations, 2) the spatial and temporal Institute for Research of the Atmosphere, Fort Collins, Colorado scales involved, and 3) the storm’s potential for rapid a Retired intensity (RI; >30 kt in 24 h; 1 kt = 0.51 m s–1) changes. -

ANNUAL SUMMARY Eastern North Pacific Hurricane Season of 2009

VOLUME 139 MONTHLY WEATHER REVIEW JUNE 2011 ANNUAL SUMMARY Eastern North Pacific Hurricane Season of 2009 TODD B. KIMBERLAIN AND MICHAEL J. BRENNAN NOAA/NWS/NCEP National Hurricane Center, Miami, Florida (Manuscript received 10 May 2010, in final form 10 September 2010) ABSTRACT The 2009 eastern North Pacific hurricane season had near normal activity, with a total of 17 named storms, of which seven became hurricanes and four became major hurricanes. One hurricane and one tropical storm made landfall in Mexico, directly causing four deaths in that country along with moderate to severe property damage. Another cyclone that remained offshore caused an additional direct death in Mexico. On average, the National Hurricane Center track forecasts in the eastern North Pacific for 2009 were quite skillful. 1. Introduction Jimena and Rick made landfall in Mexico this season, the latter as a tropical storm. Hurricane Andres also After two quieter-than-average hurricane seasons, affected Mexico as it passed offshore of that nation’s tropical cyclone (TC) activity in the eastern North Pa- southern coast. Tropical Storm Patricia briefly threat- cific basin1 during 2009 (Fig. 1; Table 1) was near nor- ened the southern tip of the Baja California peninsula mal. A total of 17 tropical storms developed, of which before weakening. seven became hurricanes and four became major hur- A parameter routinely used to gauge the overall ac- ricanes [maximum 1-min 10-m winds greater than 96 kt tivity of a season is the ‘‘accumulated cyclone energy’’ (1 kt 5 0.5144 m s21), corresponding to category 3 or (ACE) index (Bell et al. -

The Demise of a Tropical Coastal Lagoon As Breeding Habitat for Ground-Nesting Waterbirds: Unintended, but Anticipated Consequences of Development

Coastal Management ISSN: 0892-0753 (Print) 1521-0421 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ucmg20 The Demise of a Tropical Coastal Lagoon as Breeding Habitat for Ground-Nesting Waterbirds: Unintended, but Anticipated Consequences of Development Eric Mellink & Mónica E. Riojas-López To cite this article: Eric Mellink & Mónica E. Riojas-López (2017) The Demise of a Tropical Coastal Lagoon as Breeding Habitat for Ground-Nesting Waterbirds: Unintended, but Anticipated Consequences of Development, Coastal Management, 45:3, 253-269, DOI: 10.1080/08920753.2017.1303766 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/08920753.2017.1303766 View supplementary material Published online: 14 Apr 2017. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 45 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ucmg20 COASTAL MANAGEMENT 2017, VOL. 45, NO. 3, 253–269 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08920753.2017.1303766 The Demise of a Tropical Coastal Lagoon as Breeding Habitat for Ground-Nesting Waterbirds: Unintended, but Anticipated Consequences of Development Eric Mellinka and Monica E. Riojas-Lopez b aDepartamento de Biologıa de la Conservacion, Centro de Investigacion Cientıfica y de Educacion Superior de Ensenada, Ensenada, Baja California, Mexico; bDepartamento de Ecologıa, CUCBA, Universidad de Guadalajara, Zapopan, Jalisco, Mexico ABSTRACT KEYWORDS Laguna Cuyutlan (Colima, Mexico), an Important Bird Area, used to conservation; Laguna provide breeding habitat for ground-nesting waterbirds. During 2014 Cuyutlan; Laridae; Mexico and 2015, nesting efforts of laughing gull, black skimmer, and royal, gull-billed and Forster’s terns failed almost completely due to inundation, while least terns and snowy plovers fared the same during 2014. -

HURRICANE BLANCA (EP022015) 31 May – 9 June 2015

NATIONAL HURRICANE CENTER TROPICAL CYCLONE REPORT HURRICANE BLANCA (EP022015) 31 May – 9 June 2015 Richard J. Pasch and David P. Roberts National Hurricane Center 30 November 2015 GOES-15 VISIBLE SATELLITE IMAGE OF HURRICANE BLANCA AT 1500 UTC 3 JUNE 2015, NEAR ITS PEAK INTENSITY OF 125 KT. IMAGE COURTESY OF NAVAL RESEARCH LABORATORY. Blanca was a category 4 hurricane (on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale) that later made landfall on the Baja California peninsula of Mexico as a tropical storm. It was the earliest second hurricane and the earliest second major hurricane of the season in the eastern North Pacific basin, as well as the earliest landfall on record of a tropical storm on the Baja California peninsula since reasonably accurate records began in the early 1970s. Hurricane Blanca 2 Hurricane Blanca 31 MAY – 9 JUNE 2015 SYNOPTIC HISTORY Blanca appears to have originated from a tropical wave that crossed Central America on 26 May. Over the next few days, the wave moved slowly westward to the south of Central America and Mexico with limited associated shower activity until 30 May, when deep convection increased and became consolidated a few hundred miles south of Acapulco, Mexico. This development trend continued, and by 1200 UTC 31 May the cloud pattern became sufficiently well organized to designate the formation of a tropical depression centered about 320 n mi south-southwest of Acapulco. The “best track” chart of the tropical cyclone’s path is given in Fig. 1, with the wind and pressure histories shown in Figs. 2 and 3, respectively. -

2021 National Hurricane Operations Plan

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE/ National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration OFFICE OF THE FEDERAL COORDINATOR FOR METEOROLOGICAL SERVICES AND SUPPORTING RESEARCH National Hurricane Operations Plan FCM-P12-2021 Washington, DC May 2021 Hurricane Epsilon, courtesy of NOAA. FEDERAL COORDINATOR FOR METEOROLOGICAL SERVICES AND SUPPORTING RESEARCH 1325 East-West Highway, SSMC2 Silver Spring, Maryland 20910 301-628-0112 NATIONAL HURRICANE OPERATIONS PLAN FCM-P12-2021 Washington, D.C. May 2021 CHANGE AND REVIEW LOG Use this page to record changes and notices of reviews. Change Page Numbers Date Posted Initials Number (mm/dd/yyyy) 1. D-1, F-17, L-1 5/21/2021 EEM 2. 3-5, 5-1, 5-7, 5-11, 5-12, 5- 6/7/2021 EEM 18, G-2, G-3, G-10, G-24 3. 4. 5. Changes are indicated by a vertical line in the margin next to the change or by shading and strikeouts. No. Review Date Comments Initials (mm/dd/yyyy) 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. iv NATIONAL HURRICANE OPERATIONS PLAN TABLE OF CONTENTS CHANGE AND REVIEW LOG ................................................................................................... iv LIST OF FIGURES ....................................................................................................................... xi LIST OF TABLES ....................................................................................................................... xiii CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................ 1-1 1.1 General. ................................................................................................................................. -

National Hurricane Operations Plan FCM-P12-2010

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE/ National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration OFFICE OF THE FEDERAL COORDINATOR FOR METEOROLOGICAL SERVICES AND SUPPORTING RESEARCH National Hurricane Operations Plan FCM-P12-2010 Hurricane Bill - 19 August 2009 Washington, DC May 2010 THE FEDERAL COMMITTEE FOR METEOROLOGICAL SERVICES AND SUPPORTING RESEARCH (FCMSSR) DR. JANE LUBCHENCO DR. RANDOLPH LYON Chairman, Department of Commerce Office of Management and Budget MS. SHERE ABBOTT MS. VICTORIA COX Office of Science and Technology Policy Department of Transportation DR. RAYMOND MOTHA MR. EDWARD CONNOR (Acting) Department of Agriculture Federal Emergency Management Agency Department of Homeland Security DR. JOHN (JACK) L. HAYES Department of Commerce DR. EDWARD WEILER National Aeronautics and Space MR. ALAN SHAFFER Administration Department of Defense DR. TIM KILLEEN DR. ANNA PALMISANO National Science Foundation Department of Energy MR. PAUL MISENCIK MR. KEVIN (SPANKY) KIRSCH National Transportation Safety Board Science and Technology Directorate Department of Homeland Security MR. JAMES LYONS U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission DR. HERBERT FROST Department of the Interior DR. LAWRENCE REITER Environmental Protection Agency MR. KENNETH HODGKINS Department of State MR. SAMUEL P. WILLIAMSON Federal Coordinator MR. MICHAEL BABCOCK, Secretariat Office of the Federal Coordinator for Meteorological Services and Supporting Research THE INTERDEPARTMENTAL COMMITTEE FOR METEOROLOGICAL SERVICES AND SUPPORTING RESEARCH (ICMSSR) MR. SAMUEL P. WILLIAMSON, Chairman MR. BARRY SCOTT Federal Coordinator Federal Aviation Administration Department of Transportation MR. THOMAS PUTERBAUGH Department of Agriculture DR. JONATHAN M. BERKSON United States Coast Guard DR. JOHN (JACK) L. HAYES Department of Homeland Security Department of Commerce DR. DEBORAH LAWRENCE RADM DAVID TITLEY, USN Department of State United States Navy Department of Defense DR. -

Border Climate Summary Resumen Del Clima De La Frontera Issued: February 18, 2010 Tree Rings and the Monsoon in the Southwestern U.S

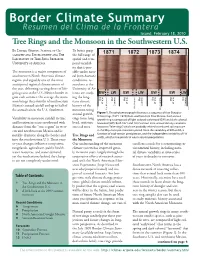

Border Climate Summary Resumen del Clima de la Frontera Issued: February 18, 2010 Tree Rings and the Monsoon in the Southwestern U.S. By Daniel Griffin, School of Ge- To better grasp ography and Development and The the full range of 1871 1872 1873 1874 Laboratory of Tree-Ring Research, spatial and tem- University of Arizona poral variabil- ity that is pos- The monsoon is a major component of sible under natu- southwestern North America’s climate ral (non-human) regime and arguably one of the most conditions, re- anticipated regional climate events of searchers at the the year, delivering varying doses of life- University of Ar- giving rains to the U.S.-Mexico border re- izona are study- EW LW EW LW EW EW LW gion each summer. On average, the mon- ing the long- Dry Dry Dry soon brings three-fourths of northwestern term climate Wet Wet Wet Wet Winter Winter Winter Winter Mexico’s annual rainfall and up to half of history of the Summer Summer Summer Pre-Monson? Pre-Monsoon? the annual rain in the U.S. Southwest. monsoon using Dry Summer annual growth Figure 1. This photomicrograph illustrates a sequence of four Douglas- fir tree rings (1871–1874) from southwestern New Mexico. Each annual Variability in monsoon rainfall in time rings from long- growth ring is composed of light-colored earlywood (EW) and dark-colored and location increases northward with lived, moisture- latewood (LW). Both 1871 and 1872 contain intra-annual density variations distance from the “core region” in west- stressed trees. known as “false rings,” which are probably related to reduced soil moisture ern and northwestern Mexico and is in the May–June pre-monsoon period. -

National Hurricane Operations Plan

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE/ National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration OFFICE OF THE FEDERAL COORDINATOR FOR METEOROLOGICAL SERVICES AND SUPPORTING RESEARCH National Hurricane Operations Plan FCM-P12-2001 Washington, DC Hurricane Keith - 1 October 2000 May 2001 THE FEDERAL COMMITTEE FOR METEOROLOGICAL SERVICES AND SUPPORTING RESEARCH (FCMSSR) MR. SCOTT B. GUDES, Chairman MR. MONTE BELGER Department of Commerce Department of Transportation DR. ROSINA BIERBAUM MS. MARGARET LAWLESS (Acting) Office of Science and Technology Policy Federal Emergency Management Agency DR. RAYMOND MOTHA DR. GHASSEM R. ASRAR Department of Agriculture National Aeronautics and Space Administration MR. JOHN J. KELLY, JR. Department of Commerce DR. MARGARET S. LEINEN National Science Foundation CAPT FRANK GARCIA, USN Department of Defense MR. PAUL MISENCIK National Transportation Safety Board DR. ARISTIDES PATRINOS Department of Energy MR. ROY P. ZIMMERMAN U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission DR. ROBERT M. HIRSCH Department of the Interior DR. JOEL SCHERAGA (Acting) Environmental Protection Agency MR. RALPH BRAIBANTI Department of State MR. SAMUEL P. WILLIAMSON Federal Coordinator MR. RANDOLPH LYON Office of Management and Budget MR. JAMES B. HARRISON, Executive Secretary Office of the Federal Coordinator for Meteorological Services and Supporting Research THE INTERDEPARTMENTAL COMMITTEE FOR METEOROLOGICAL SERVICES AND SUPPORTING RESEARCH (ICMSSR) MR. SAMUEL P. WILLIAMSON, Chairman DR. JONATHAN M. BERKSON Federal Coordinator United States Coast Guard Department of Transportation DR. RAYMOND MOTHA Department of Agriculture DR. JOEL SCHERAGA (Acting) Environmental Protection Agency MR. JOHN E. JONES, JR. Department of Commerce MR. JOHN GAMBEL Federal Emergency Management Agency CAPT FRANK GARCIA, USN Department of Defense DR. RAMESH KAKAR National Aeronautics and Space MR. -

REVIEW Eastern North Pacific Hurricane Season of 2009

VOLUME 139 MONTHLY WEATHER REVIEW JUNE 2011 REVIEW Eastern North Pacific Hurricane Season of 2009 TODD B. KIMBERLAIN AND MICHAEL J. BRENNAN NOAA/NWS/NCEP National Hurricane Center, Miami, Florida (Manuscript received 10 May 2010, in final form 10 September 2010) ABSTRACT The 2009 eastern North Pacific hurricane season had near normal activity, with a total of 17 named storms, of which seven became hurricanes and four became major hurricanes. One hurricane and one tropical storm made landfall in Mexico, directly causing four deaths in that country along with moderate to severe property damage. Another cyclone that remained offshore caused an additional direct death in Mexico. On average, the National Hurricane Center track forecasts in the eastern North Pacific for 2009 were quite skillful. 1. Introduction Jimena and Rick made landfall in Mexico this season, the latter as a tropical storm. Hurricane Andres also After two quieter-than-average hurricane seasons, affected Mexico as it passed offshore of that nation’s tropical cyclone (TC) activity in the eastern North Pa- southern coast. Tropical Storm Patricia briefly threat- cific basin1 during 2009 (Fig. 1; Table 1) was near nor- ened the southern tip of the Baja California peninsula mal. A total of 17 tropical storms developed, of which before weakening. seven became hurricanes and four became major hur- A parameter routinely used to gauge the overall ac- ricanes [maximum 1-min 10-m winds greater than 96 kt tivity of a season is the ‘‘accumulated cyclone energy’’ (1 kt 5 0.5144 m s21), corresponding to category 3 or (ACE) index (Bell et al.