Martin Luther King, Jr. Day Writing Awards Carnegie Mellon University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Franklin Park Grouping

FINAL PARISH GROUPINGS Vicariate One 1 Bellevue/Emsworth/ Franklin Park Grouping Parish Grouping Administrator: • Assumption of the Blessed Father John Bachkay Virgin Mary Senior Parochial Vicar: • St. John Neumann Father Kenneth Keene • Sacred Heart Parochial Vicar: Father David Green School: Deacon: Northside Catholic School (NHCRES) Deacon Richard Caruso Mass Attendance = 2,600 Maximum Number of Masses: 9 Category: B Etna/Glenshaw/ Millvale Grouping Parish Grouping Administrator: • All Saints Father James Gretz • St. Bonaventure Senior Parochial Vicar: • Holy Spirit Father James Mazurek • St. Nicholas Parochial Vicar: Father Miroslaw Stelmaszczyk School: In Residence: Blessed Trinity Academy (NHCRES) Father Gerald Lutz Deacons: Mass Attendance = 2,450 Deacon Stephen Byers Maximum Number of Masses: 9 Deacon Stephen Kisak Category: C Deacon Charles Rhoads Allison Park/Glenshaw Grouping Parish Grouping Administrator: • St. Mary of the Assumption Father Timothy Whalen • St. Ursula Parochial Vicar: Father Ernest Strzelinski School: Parish Chaplains: Blessed Trinity Academy (NHCRES) Father Joseph Luisi Father John McKenna Mass Attendance = 2,150 Deacons: Maximum Number of Masses: 9 Deacon Francis Dadowski, Jr. Category: C Deacon Richard Ernst Observatory Hill/Perrysville/ Ross/West View Grouping Parish Grouping Administrator: Father John Rushofsky • St. Athanasius Senior Parochial Vicar: • Incarnation of the Lord Father Michael Maranowski Parochial Vicar: • St. Sebastian Father Michael Zavage • St. Teresa of Avila Parish Chaplain: Father James Dolan Institutional Chaplain/Tribunal Consultant: School: Father William Dorner Holy Cross Academy (NHCRES) In Residence: Father Leroy DiPietro Father Innocent Onuah Mass Attendance = 4,150 Deacons: Deacon Richard Cessar Maximum Number of Masses: 10 Deacon Gary Comer Category: B Deacon Robert Koslosky Deacon William Palamara, Jr. Deacon David Witter North Side Grouping Parish Grouping Moderator Team Ministry: • St. -

Allderdice 2409 Shady Avenue Pittsburgh, PA 15217 412-422-4851 • Go Through Oakmont And/Or Verona to Washington Boulevard •

Allderdice 2409 Shady Avenue Pittsburgh, PA 15217 412-422-4851 • Go through Oakmont and/or Verona to Washington Boulevard • Right turn onto Washington Boulevard • Follow onto 5 th Avenue at Penn Avenue • Left onto Shady Avenue at Pittsburgh Center for the ARTS • Turn left onto Forward Avenue • Turn left onto Beechwood Avenue • Turn right onto English Lane • Follow to parking lot – field at top of stairs Apollo-Ridge 1825 State Route 56 Spring Church, PA 15685 724-478-6000 – 724-478-9775 (Fax) From Route 28: • Get of 366 Tarentum Bridge • Cross the bridge following 366 • Take Route 56 East towards Leechburg • Follow Route 56 East through Vandergrift • Cross Vandergrift Bridge, follow Route 56 East into Apollo (after crossing the bridge, turn right) • Turn left at light in Apollo, football stadium is ½ mile on the left Aquinas Academy 2308 West Hardies Road Gibsonia, PA 15044 724-444-0722 Aquinas Academy (Dolan Field) From Turnpike Exit 39: • Exit I-76, Pennsylvania Turnpike via ramp at Exit 30 PA 8 to Pittsburgh/Butler • Keep right at the fork in the ramp • Bear right on PA-8, William Flynn Hwy and go north for 500 feet staying in the left lane (there will be alight and a BP station on your left) • Turn left at the light onto West Hardies Road and go west for 2.0 miles (the school will be on your left just past St. Catherine of Sweden Church • The field is behind the school Avonworth 304 Josephs Lane Pittsburgh, PA 15237 412-847-0942 / 412-366-7603 (Fax) High School Gym – Girls’ JV & Varsity Volleyball Middle School Gym – 7/8th Grade Girls’ Basketball Lenzner Field – Varsity, JV, 7/8 th Football; Varsity, JV Girls’ & Boys’ Soccer High School Field (behind building) – 7/8 Soccer, Boys & Girls Ohio Township Community Park – Varsity Cross Country High School Gym, Middle School Gym, Lenzner Field and High School Field From the North: Take 79 South to 279S exiting at the Camp Horne Road Exit. -

Our Advertisers Get Results. So Can You

OUR ADVERTISERS GET RESULTS. SO CAN YOU. Serving Allegheny, Beaver, Butler, Washington HERE ARE SOME OF OUR LONG-TIME and Westmoreland Counties ADVERTISERS. YOU MAY RECOGNIZE THEM. Glossy Wrap - Back Cover, Inside Front & Inside Back Achieva PA Virtual Altimate Air Penn State COVER Aquinas Academy Pittsburgh Ballet 1/2 H Camp Deer Creek Pittsburgh Zoo FULL PAGE Carlow University Pittsburgh Children’s Museum Carnegie Science Center Pittsburgh Cultural Trust COVER Carnegie Museums PPG Place 1/2 H Community Day School River Pediatric Therapies Duquesne University St. Edmunds Ellis School Shady Side Academy Interior Newsprint Pages Giant Eagle Sewickley Academy Gymkhana TEIS 1/2 H PPG Place Tendercare 1/3 SQUARE Highmark UPMC 1/3 Kentucky Avenue School Urban Pathways verticle Kiski School Vincentian Academy 1/3 SQUARE 1/6 V 1/6 H Knowledge Learning Montessori Center Academy Magee Hospital Western PA Montessori 1/12 1/12 Mercy Hospital Western PA School for Deaf PA Cyber Winchester Thurston We love Pittsburgh Parent: “Pittsburgh Parent Magazine reaches our target clientele and working with staff there has always been an easy and pleasant experience! Over the years, we’ve enjoyed great success with promotional programs and coupons in Pittsburgh Parent Magazine.” — Liza Barbour, Gymkhana Gymnastics “Working with Pittsburgh Parent Magazine gives ACHIEVA the opportunity to reach parents throughout the Pittsburgh region. As a non-profit, ACHIEVA has to be selective in where we use our advertising dollars. Through Pittsburgh Parent ACHIEVA has confidence that our Early Intervention services are targeting the proper market.” — Danielle Parson-Rush, ACHIEVA “I have advertised with Pittsburgh Parent through the Pittsburgh Cultural Trust for the Citizens Bank Children’s Theater Series, EQT Children’s Theater Festival and PNC Broadway Across America Series. -

September 2008

THE DUQUESNE U NIVERSI T Y SEPTEMBER 2008 Smoking Policy Changes Meet the Freshmen Deep Thoughts Tune in Fridays Learn about the new smoking policy Gain insights into the incoming fresh- Science, philosophy and faith con- WQED-FM will be broadcasting at Duquesne in the Q&A. Page 2 man class. Page 5 verge at the first Pascal Day event. Duquesne music events on Friday Page 12 evenings. Page 13 Duquesne Moves into First Tier of Ranking U.S. News & World Report’s annual commend our faculty, staff and adminis- first-ever, Board-approved 2003-2008 The annual U.S. News & World Report ranking of America’s Best Colleges, trators for setting and meeting such high strategic plan, with the ultimate goal rankings evaluate universities on the which was released in August, has moved standards and for the extraordinary and of entering the first ranks of American basis of 15 different qualities, including Duquesne University into the top tier of pervasive focus on our mission.” Catholic higher education. peer assessment, graduation and reten- national universities. Under Dougherty’s leadership, the Other notable Catholic universities tion, class size, student/faculty ratio, “This ranking is another indepen- University has achieved record-breaking in the top national tier include Ford- selectivity, SAT/ACT scores, freshman dent confirmation of the commitment enrollment and has attracted the most ham, Marquette, St. Louis, Dayton, San retention, alumni giving, financial re- of the entire Duquesne community to academically talented students in its Diego, San Francisco, Chicago’s Loy- sources and other categories. academic excellence,” said Dr. Charles history. -

2019-20 Atlantic 10 Commissioner's Honor Roll

2019-20 Atlantic 10 Commissioner’s Honor Roll Name Sport Year Hometown Previous School Major DAVIDSON Alexa Abele Women's Tennis Senior Lakewood Ranch, FL Sycamore High School Economics Natalie Abernathy Women's Cross Country/Track & Field First Year Student Land O Lakes, FL Land O Lakes High School Undecided Cameron Abernethy Men's Soccer First Year Student Cary, NC Cary Academy Undecided Alex Ackerman Men's Cross Country/Track & Field Sophomore Princeton, NJ Princeton High School Computer Science Sophia Ackerman Women's Track & Field Sophomore Fort Myers, FL Canterbury School Undecided Nico Agosta Men's Cross Country/Track & Field Sophomore Harvard, MA F W Parker Essential School Undecided Lauryn Albold Women's Volleyball Sophomore Saint Augustine, FL Allen D Nease High School Psychology Emma Alitz Women's Soccer Junior Charlottesville, VA James I Oneill High School Psychology Mateo Alzate-Rodrigo Men's Soccer Sophomore Huntington, NY Huntington High School Undecided Dylan Ameres Men's Indoor Track First Year Student Quogue, NY Chaminade High School Undecided Iain Anderson Men's Cross Country/Track & Field Junior Helena, MT Helena High School English Bryce Anthony Men's Indoor Track First Year Student Greensboro, NC Ragsdale High School Undecided Shayne Antolini Women's Lacrosse Senior Babylon, NY Babylon Jr Sr High School Political Science Chloe Appleby Women's Field Hockey Sophomore Charlotte, NC Providence Day School English Lauren Arkell Women's Lacrosse Sophomore Brentwood, NH Phillips Exeter Academy Physics Sam Armas Women's Tennis -

Schools Eligible to Receive Opportunity Scholarship Students In

Schools Eligible to Receive Opportunity Scholarship Students in the 2015-16 School Year For additional details about any of the schools listed, please refer to the contact information provided. Additional information about the Opportunity Scholarship Tax Credit Program can be found on the Pennsylvania Department of Community and Economic Development's website at www.newpa.com/ostc. Designation (Public/ County School Name Contact Address Phone Number Email Address Tuition and Fees for the 2014-15 School Year Nonpublic) Adams County Christian Norma Coates, 1865 Biglerville Rd., Elementary school tuition - $4,680 (K-6); High school Adams Academy Nonpublic Secretary Gettysburg, PA 17325 717-334-6793 [email protected] tuition - $4,992 (7-12) Registration fee- $150 Mrs. Patricia Foltz, 316 North St., Tuition - $3,125 (Catholic); $4,200 (Non-Catholic); Adams Annunciation B.V.M. Nonpublic Principal McSherrytown, PA 17344 717-637-3135 [email protected] Registration fee - $75 140 S Oxford Ave., Maureen C. Thiec, McSherrystown, PA Adams Delone Catholic High School Nonpublic Ed.D., Principal 17344 717-637-5969 [email protected] Tuition - $5,400 (Catholic); $7,080 (Non-Catholic) Karen L. Trout, 3185 York Rd., Adams Freedom Christian Schools Nonpublic Principal Gettysburg, PA 17325 717-624-3884 [email protected] $3,240 Gettysburg Seventh-Day Marian E. Baker, 1493 Biglerville Rd., Adams Adventist Church School Nonpublic Principal Gettysburg, PA 17325 717-338-1031 [email protected] Tuition for kindergarten - $3,800; Registration fee - $325 Donna Hoffman, 101 N Peter St., New Adams Immaculate Conception Nonpublic Principal Oxford, PA 17350 717-624-2061 [email protected] Tuition - $2,900 (Catholic); $4,700 (Non-Catholic) Crystal Noel, 55 Basicila Rd., Hanover, Adams Sacred Heart Nonpublic Principal PA 17331 717-632-8715 [email protected] Tuition - $2,875 (Catholic); $3,950 (Non-Catholic) Rebecca Sieg, 465 Table Rock Rd., Adams St. -

2019 Website Print Advertising Sheet

OUR ADVERTISERS GET RESULTS. SO CAN YOU. Serving Allegheny, Beaver, Butler, Washington HERE ARE SOME OF OUR LONG-TIME and Westmoreland Counties ADVERTISERS. YOU MAY RECOGNIZE THEM. Glossy Wrap - Back Cover, Inside Front & Inside Back Achieva PA Virtual Altimate Air Penn State COVER FULL PAGE Aquinas Academy Pittsburgh Ballet 1/2 H Camp Deer Creek Pittsburgh Zoo Carlow University Pittsburgh Children’s Museum Carnegie Science Center Pittsburgh Cultural Trust COVER Carnegie Mellon University PPG Place 1/2 H Carnegie Museums River Pediatric Therapies Community Day School St. Edmunds Duquesne University Shady Side Academy Interior Newsprint Pages Giant Eagle Sewickley Academy Gold Fish Swim School TEIS Gymkhana Tendercare 1/4 1/2 H 1/3 SQUARE PPG Place UPMC 1/3 Highmark Urban Pathways verticle Kentucky Avenue School Vincentian Academy 1/3 SQUARE 1/6 V 1/6 H Knowledge Learning Montessori Center Academy Magee Hospital Western PA Montessori 1/12 1/12 Mercy Hospital Western PA School for Deaf PA Cyber Weirton Medical Center We love Pittsburgh Parent: “Pittsburgh Parent Magazine reaches our target clientele and working with staff there has always been an easy and pleasant experience! Over the years, we’ve enjoyed great success with promotional programs and coupons in Pittsburgh Parent Magazine.” — Liza Barbour, Gymkhana Gymnastics “Working with Pittsburgh Parent Magazine gives ACHIEVA the opportunity to reach parents throughout the Pittsburgh region. As a non-profit, ACHIEVA has to be selective in where we use our advertising dollars. Through Pittsburgh Parent ACHIEVA has confidence that our Early Intervention services are targeting the proper market.” — Danielle Parson-Rush, ACHIEVA “I have advertised with Pittsburgh Parent through the Pittsburgh Cultural Trust for the Citizens Bank Children’s Theater Series, EQT Children’s Theater Festival and PNC Broadway Across America Series. -

309 Church Road Athletic Office Bethel Park, PA 15102 412-854-8548

309 Church Road Athletic Office Bethel Park, PA 15102 412-854-8548 All directions are to the High School facilities unless otherwise noted. These directions are for reference purposes only and as roads and landmarks change these directions may vary from the time of print. School addresses have been included if you are using a GPS or Online direction service to help insure accuracy. Please check with each individual school to confirm directions and any potential construction or location changes. In your travels, if you notice any discrepancies in these directions, please contact the athletic office so that we may update our records to better assist Black Hawk Fans in the future. Thank you! A ALBERT GALLATIN RD 5 Box 175 A Uniontown, PA 15401 724-564-2024 Route 51 South to the outskirts of Uniontown. Look for the shopping center and make a right onto 119 South. Take 119 by pass. Exit onto 119 south and then turn right at the exit. You will still be on Route 119. Go five miles until you come to a crossroads (There will be a small coal company on the left) - make a right at the crossroads and slow down because you want to make the first sharp left. The school will be less than a minute away. Jr. High School Route 51 south to Rt. 119 south. Go to Smithfield at light and turn right on route 166 south to the junior high school. (TAYLOR) ALDERDICE 2409 Shady Avenue Pittsburgh, PA 15217 412-422-4800 Take Lebanon Church Road to 885 to Streets Run Road through Homestead to the High Level Bridge. -

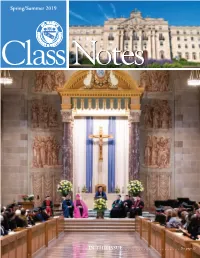

Class Notes Spring/Summer 2019 Dr

Spring/Summer 2019 Class NNootteess IN THIS ISSUE . See page 27 Faculty News School of Theology Faculty, Graduation 2019 This year, Fr. Phillip J. Brown, P.S.S. pub - Recent Revisions to the Catechism. Also in March Fr. Brown was in lished two articles: “Prescription and the Washington, DC attending the Anniversary Celebration of the Usefulness of Time” in A Service Beyond All Election of Pope Francis at the Apostolic Nunciature. In late Recompense: Studies Offered in Honor of Msgr. March, Fr. Brown attended the annual meeting of the St. Thomas Thomas J. Green CUA Press and “The Right of More Society of Maryland Board of Trustees in which he was re- Defense and Due Process: Fulcrum of Justice, elected to serve on the Board of Trustees. In April, Fr. Brown Heart of the Law” Studia Canonica 52/2 (2018). attended a conference on the Role of Lawyers in the Clergy Fr. Brown, an active member of the St. Thomas Abuse Crisis at Georgetown University Law Center in More Society and the Canon Law Society of America, participat - Washington, DC. At the conclusion of the academic year Fr. ed in several board meetings this year as well as representing St. Brown attending the Biennial Sulpician Provincial Retreat in Mary’s at the National Association of Catholic Theological Seattle, Washington. On a monthly basis, Fr. Brown continues Schools annual meeting in Chicago, IL from September 27-29. to attend meetings as a Chaplain for Teams of Our Lady. St. Mary’s was honored to host the annual St. Thomas More Society Red Mass and Award Dinner in October and St. -

Allegheny County

Allegheny County: Avonworth School District Avonworth High School Avonworth Elementary School Baldwin Whitehall W Robert Paynter Elementary School Harrison Middle School Baldwin Senior High School Beattie Career and Technology Center Carlynton School District Carnegie Elementary School Carlynton Junior Senior High School Chartiers Valley School District Chartiers Valley Primary School Chartiers Valley Intermediate School Cornell School District Cornell School Deer Lakes East Union Intermediate School Deer Lakes High School Eden Christian Academy Elizabeth Forward School District William Penn Elementary School Elizabeth Forward Middle School Fox Chapel Area School District Fox Chapel Area High School Gateway School District Dr. Cleveland Steward Jr. Elementary School Moss Side Middle School Hampton Township School District Central Elementary School Poff Elementary School Wyland Elementary School Hampton High School Highlands School District Highlands Middle School Hillcrest Christian Academy Imani Christian Academy Keystone Oaks School District Dormont Elementary School Fred Aiken Elementary School Myrtle Elementary School McKeesport Area School District Centennial Elementary School Montour School District David E Williams Middle School Montour High School Moon Area School District Bon Meade Elementary School J A Allard Elementary School J H Brooks Elementary School Richard J Hyde Elementary School McCormick Elementary School Moon Area High School Mt. Lebanon School District Mt. Lebanon High School North Allegheny School District North -

Elite Top 100 April 17Th, 2019 2 · WEDNESDAY, APRIL 17, 2019 TRIB TOTAL MEDIA Meet the Judges

Outstanding YOung Citizen Elite Top 100 April 17th, 2019 2 · WEDNESDAY, APRIL 17, 2019 TRIB TOTAL MEDIA Meet the Judges As past president of her local Rotary Club, Kary officer for the Annual Fund Letter from Milan was the youngest individual and only the at Saint Vincent College in fourth female to hold this position in the club’s Latrobe. She earned a Bach- near 100-year history. As Kary has advanced elor of Arts degree from at the Rotary International district and zone lev- Saint Vincent and received the president els, central to her success in this organization, the college’s Alumna of Dis- and life, has been her whole-hearted belief in tinction Award. Molly earned the organization’s commit- an MBA from Seton Hill The Trib Total Media is remarkable. They are ment to service and credo, University. She is involved Outstanding Young Citizen leaders in not only their “Service Above Self.” Kary, with several community organizations and is a Awards Program is a long- schools but their commu- who has 18 years of experi- recipient of the Westmoreland County Win- standing tradition and one nities, as well. ence in higher education, ners’ Circle Community Service Award. Molly that I look forward to each We are honored to have the nonprofit sector, and presently serves on the Mental Health America year. the opportunity to give corporate communication Southwestern Pennsylvania Board of Directors. This year, we received them the recognition they within the Greater Pitts- She is a past president of the MHA Board and 489 outstanding nomina- deserve. -

A Tour of the Vatican Library

Catholic Higher Education: Its Origins in the United States and Western Pennsylvania Michael T. Rizzi, Ed.D. Higher education is one of the most visible ministries of the chians. In doing so, he planted the seeds of what would eventually Catholic Church in the United States. There are over 200 Amer- become the Diocese of Pittsburgh. ican Catholic colleges and universities, nine of which are located in Western Pennsylvania. Although many of these institutions Since the Council of Trent in the sixteenth century, Catholics today are modern, comprehensive universities, their origins were have always operated some schools specifically to train clergy and frequently much humbler, and they often came into existence only others to educate the public.3 This was as true in the United States by overcoming major challenges and obstacles. as it was in Europe. Seminaries like St. Mary’s were seen first and foremost as a support system for the Church and were kept The story of Catholic higher education in America is a fasci- separate from colleges like Georgetown that served lay students.4 nating one, and the Pittsburgh area played a significant role in Whereas Protestants founded schools like Yale and Princeton to its development. Western Pennsylvania’s Catholic colleges were train ministers,5 Catholics were more likely to view their colleges typical in many ways, but also played an important role in shaping as a community resource, designed primarily to provide access to the Church’s approach to higher education nationally. This article education. Although it would have been more financially efficient will discuss the early history of Catholic higher education in the to educate both laypeople and seminarians on a single campus, this United States, especially as it influenced (and was influenced by) generally happened only in places where Catholics lacked the re- the Pittsburgh region.