Brucella Species

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

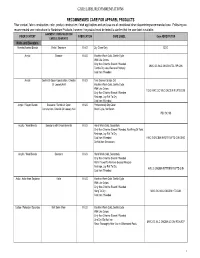

Care Label Recommendations

CARE LABEL RECOMMENDATIONS RECOMMENDED CARE FOR APPAREL PRODUCTS Fiber content, fabric construction, color, product construction, finish applications and end use are all considered when determining recommended care. Following are recommended care instructions for Nordstrom Products, however; the product must be tested to confirm that the care label is suitable. GARMENT/ CONSTRUCTION/ FIBER CONTENT FABRICATION CARE LABEL Care ABREVIATION EMBELLISHMENTS Knits and Sweaters Acetate/Acetate Blends Knits / Sweaters K & S Dry Clean Only DCO Acrylic Sweater K & S Machine Wash Cold, Gentle Cycle With Like Colors Only Non-Chlorine Bleach If Needed MWC GC WLC ONCBIN TDL RP CIIN Tumble Dry Low, Remove Promptly Cool Iron If Needed Acrylic Gentle Or Open Construction, Chenille K & S Turn Garment Inside Out Or Loosely Knit Machine Wash Cold, Gentle Cycle With Like Colors TGIO MWC GC WLC ONCBIN R LFTD CIIN Only Non-Chlorine Bleach If Needed Reshape, Lay Flat To Dry Cool Iron If Needed Acrylic / Rayon Blends Sweaters / Gentle Or Open K & S Professionally Dry Clean Construction, Chenille Or Loosely Knit Short Cycle, No Steam PDC SC NS Acrylic / Wool Blends Sweaters with Embelishments K & S Hand Wash Cold, Separately Only Non-Chlorine Bleach If Needed, No Wring Or Twist Reshape, Lay Flat To Dry Cool Iron If Needed HWC S ONCBIN NWOT R LFTD CIIN DNID Do Not Iron Decoration Acrylic / Wool Blends Sweaters K & S Hand Wash Cold, Separately Only Non-Chlorine Bleach If Needed Roll In Towel To Remove Excess Moisture Reshape, Lay Flat To Dry HWC S ONCBIN RITTREM -

Histopathology and Laboratory Features of Sexually Transmitted Diseases

Histopath & Labs for STIs Endo, Energy and Repro 2017-2018 HISTOPATHOLOGY AND LABORATORY FEATURES OF SEXUALLY TRANSMITTED DISEASES Dominck Cavuoti, D.O. Phone: 469-419-3412 Email: [email protected] LEARNING OBJECTIVES: • Identify the etiologic agents causing pelvic inflammatory disease and the pathologic changes they produce. • Discuss the characteristic clinical and pathologic findings caused by herpes simplex virus (HSV) infections: a. fever blisters b. genital herpes simplex virus infection c. disseminated neonatal HSV • Describe the pathologic changes produced by Treponema pallidum. • Describe the clinical features and pathologic changes produced by Chlamydia trachomatisand Neisseria gonorrhoeae • Describe the clinical and laboratory features of vaginal infections including: Trichomonas, Candida, and bacterial vaginosis. • Describe the clinical and laboratory features of ectoparasite infections PURPOSE OF THE LECTURE: 1. To describe the various agents of sexually transmitted diseases and their disease manifestations 2. To describe the pathologic features associated with STDs 3. To introduce some of the laboratory aspects of STDs TERMS INTRODUCED IN LECTURE: Condyloma lata Disseminated gonococcal infection Gummatous syphilis Lymphogranuloma venereum Pelvic inflammatory disease Rapid Plasma Reagin (RPR) Salpingitis Syphilis/endarteritis obliterans Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) Treponema pallidum particle agglutination (TPPA) Histopath & Labs for STIs Endo, Energy and Repro 2017-2018 MAJOR CONCEPTS EMPHASIZED IN LECTURE I. Syphilis (Will be covered by Dr. Norgard in later lecture). II. Gonorrhea A. Causative agent: Neisseria gonorrhoeae, a Gram negative diplococcus. Humans are the only natural reservoir. Infection is acquired via direct contact with the mucosa of an infected person. The incubation period averages 2-5 days with a range of 1-14 days. -

Care Labelling Guide

Care Labelling Guide This chart is for guidance only and should be read in conjunction with the ACCC Care labelling for Clothing Guide which specifies the mandatory standards for care labelling based on the Australian/New Zealand Standard (AS/NZS) 1957:1998, Textiles—Care labelling with variations and additions made by Consumer Protection Notice No. 25 of 2010. In Australia, care instructions must be permanently attached to articles, be written in English, and be appropriate for the care of the article. Additional symbols may be used to clarify the instructions but symbols alone are not sufficient. As a minimum, laundering instructions include (in order) four symbols: washing, bleaching, drying, and ironing. Drycleaning instructions include one symbol. Professional Wet Cleaning symbols are included for information only as they are not currently recognised in Australia. Washing The washtub symbol tells you how the garment should be washed. The number inside the washtub is the maximum wash temperature. A bar underneath the washtub indicates that the garment should have mild treatment or washed using the Permanent Press setting. Two lines underneath the washtub indicate gentle or delicate treatment. Normal Permanent Press Delicate / Gentle Hand Wash 95°c 70°c 60°c 50°c 40°c 30°c Do Not Wring Do Not Wash Bleaching The triangle symbol gives information about whether it is safe to bleach the garment. Any Bleach (when Only non-chlorine Do Not Bleach needed) bleach (when needed) Drying Tumble Dry - Cycles Normal Permanent Press Delicate / Gentle Do not tumble dry © 2013, Drycleaning Institute of Australia Limited Tumble Dry - Settings Any Heat High Medium Low No Heat / Air Line Dry - Hang to dry Drip Dry Dry Flat In the shade Do not dry Ironing The Iron symbol provides information on how the garment should be ironed. -

Brucella Canis and Public Health Risk İsfendiyar Darbaz , Osman Ergene

DOI: 10.5152/cjms.2019.694 Review Brucella canis and Public Health Risk İsfendiyar Darbaz , Osman Ergene Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Near East University School of Veterinary Medicine, Nicosia, Cyprus ORCID IDs of the authors: İ.D. 0000-0001-5141-8165; O.E. 0000-0002-7607-4044. Cite this article as: Darbaz İ, Ergene O. Brucella Canis and Public Health Risk. Cyprus J Med Sci 2019; 4(1): 52-6. Pregnancy losses in dogs are associated with many types of bacteria. Brucella canis is reported to be one of the most important bacterial species causing pregnancy loss in dogs. Dogs can be infected by 4 out of 6 Brucella species (B. canis, B. abortus, B. melitensis, and B. suis). B. canis is a Gram- negative coccobacillus first isolated by Leland Carmichael and is a cause of infertility in both genders. It causes late abortions in female dogs and epididymitis in male dogs. Generalized lymphadenitis, discospondylitis, and uveitis are shown as the other major symptoms. B. canis infections can easily be formed as a result of the contamination of the oronasal, conjunctival, or vaginal mucosa . Infection can affect all dog breeds and people. While morbidity may be high in infection, mortality has been reported to be low. Most dogs are asymptomatic during infection, and it is difficult to convince their owners that their dogs are sick and should not be used in reproduction. The diagnosis of the disease is quite complex. Serological tests may provide false results or negative results in chronic cases. Therefore, diagnosis should be defined by combining the results of serological studies and bacterial studies to provide the most accurate result. -

Reportable Diseases and Conditions

KINGS COUNTY DEPARTMENT of PUBLIC HEALTH 330 CAMPUS DRIVE, HANFORD, CA 93230 REPORTABLE DISEASES AND CONDITIONS Title 17, California Code of Regulations, §2500, requires that known or suspected cases of any of the diseases or conditions listed below are to be reported to the local health jurisdiction within the specified time frame: REPORT IMMEDIATELY BY PHONE During Business Hours: (559) 852-2579 After Hours: (559) 852-2720 for Immediate Reportable Disease and Conditions Anthrax Escherichia coli: Shiga Toxin producing (STEC), Rabies (Specify Human or Animal) Botulism (Specify Infant, Foodborne, Wound, Other) including E. coli O157:H7 Scrombroid Fish Poisoning Brucellosis, Human Flavivirus Infection of Undetermined Species Shiga Toxin (Detected in Feces) Cholera Foodborne Disease (2 or More Cases) Smallpox (Variola) Ciguatera Fish Poisoning Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome Tularemia, human Dengue Virus Infection Influenza, Novel Strains, Human Viral Hemorrhagic Fever (Crimean-Congo, Ebola, Diphtheria Measles (Rubeola) Lassa, and Marburg Viruses) Domonic Acid Poisoning (Amnesic Shellfish Meningococcal Infections Yellow Fever Poisoning) Novel Virus Infection with Pandemic Potential Zika Virus Infection Paralytic Shellfish Poisoning Plague (Specify Human or Animal) Immediately report the occurrence of any unusual disease OR outbreaks of any disease. REPORT BY PHONE, FAX, MAIL WITHIN ONE (1) WORKING DAY Phone: (559) 852-2579 Fax: (559) 589-0482 Mail: 330 Campus Drive, Hanford 93230 Conditions may also be reported electronically via the California -

Brucellosis Tip Sheet June 2018

BRUCELLOSIS Background Brucellosis is an infectious disease caused by Brucella species such as Brucella melitensis, Brucella abortus, and Brucella suis. People can get the disease when they are in contact with infected animals or animal products contaminated with the bacteria. From 1993 through 2010, the number of brucellosis cases reported in the US ranged from 79 to 139, with an average of 109 cases per year. In 2010, the highest number (56.5%) of brucellosis cases was reported by California, Texas, Arizona, and Florida. Michigan reported four cases that same year (range=0‐10 cases per year). Signs and Symptoms Acute Non‐specific: fever, sweats, malaise, anorexia, headache, pain in muscles, joint, and/or back pain, fatigue Sub‐clinical infections are common Lymphadenopathy (10–20%), splenomegaly (20–30%) Chronic Recurrent fever Arthritis and spondylitis Swelling of the testicle and scrotum area Swelling of the heart (endocarditis) Swelling of the liver and/or spleen Neurologic symptoms (in up to 5% of all cases) Possible focal organ involvement Chronic fatigue Depression Brucellosis in Pregnant Women Brucellosis during pregnancy carries the risk of causing spontaneous abortion, particularly during the first and second trimesters; therefore, women should receive prompt medical treatment with the proper antimicrobials. Incubation Period Highly variable (5 days–6 months) Average onset 2–4 weeks Transmission Ingestion: The most common way to be infected is by eating or drinking unpasteurized/raw dairy products. When sheep, goats, cows, or camels are infected, their milk becomes contaminated with the bacteria. If milk from infected animals is not pasteurized, the infection will be transmitted to people who consume the milk and/or cheese products. -

Catalogue of Bacteria Shapes

We first tried to use the most general shape associated with each genus, which are often consistent across species (spp.) (first choice for shape). If there was documented species variability, either the most common species (second choice for shape) or well known species (third choice for shape) is shown. Corynebacterium: pleomorphic bacilli. Due to their snapping type of division, cells often lie in clusters resembling chinese letters (https://microbewiki.kenyon.edu/index.php/Corynebacterium) Shown is Corynebacterium diphtheriae Figure 1. Stained Corynebacterium cells. The "barred" appearance is due to the presence of polyphosphate inclusions called metachromatic granules. Note also the characteristic "Chinese-letter" arrangement of cells. (http:// textbookofbacteriology.net/diphtheria.html) Lactobacillus: Lactobacilli are rod-shaped, Gram-positive, fermentative, organotrophs. They are usually straight, although they can form spiral or coccobacillary forms under certain conditions. (https://microbewiki.kenyon.edu/index.php/ Lactobacillus) Porphyromonas: A genus of small anaerobic gram-negative nonmotile cocci and usually short rods thatproduce smooth, gray to black pigmented colonies the size of which varies with the species. (http:// medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/Porphyromonas) Shown: Porphyromonas gingivalis Moraxella: Moraxella is a genus of Gram-negative bacteria in the Moraxellaceae family. It is named after the Swiss ophthalmologist Victor Morax. The organisms are short rods, coccobacilli or, as in the case of Moraxella catarrhalis, diplococci in morphology (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moraxella). *This one could be changed to a diplococcus shape because of moraxella catarrhalis, but i think the short rods are fair given the number of other moraxella with them. Jeotgalicoccus: Jeotgalicoccus is a genus of Gram-positive, facultatively anaerobic, and halotolerant to halophilicbacteria. -

Porphyromonas Gingivalis, Strain F0566 Catalog

Product Information Sheet for HM-1141 Porphyromonas gingivalis, Strain F0566 immediately upon arrival. For long-term storage, the vapor phase of a liquid nitrogen freezer is recommended. Freeze- thaw cycles should be avoided. Catalog No. HM-1141 Growth Conditions: For research use only. Not for human use. Media: Supplemented Tryptic Soy broth or equivalent Contributor: Tryptic Soy agar with 5% defibrinated sheep blood or Floyd E. Dewhirst, D.D.S., Ph.D., Senior Member of the Staff, Supplemented Tryptic Soy agar or equivalent Department of Microbiology and Jacques Izard, Assistant Incubation: Member of the Staff, Department of Molecular Genetics, The Temperature: 37°C Forsyth Institute, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA Atmosphere: Anaerobic Propagation: Manufacturer: 1. Keep vial frozen until ready for use, then thaw. BEI Resources 2. Transfer the entire thawed aliquot into a single tube of broth. Product Description: 3. Use several drops of the suspension to inoculate an Bacteria Classification: Porphyromonadaceae, agar slant and/or plate. Porphyromonas 4. Incubate the tube, slant and/or plate at 37°C for 24 to Species: Porphyromonas gingivalis 72 hours. Broth cultures should include shaking. Strain: F0566 Original Source: Porphyromonas gingivalis (P. gingivalis), Citation: strain F0566 was isolated in October 1987 from the tooth Acknowledgment for publications should read “The following of a patient diagnosed with moderate periodontitis in the reagent was obtained through BEI Resources, NIAID, NIH as United States.1 part of the Human Microbiome Project: Porphyromonas Comments: P. gingivalis, strain F0566 (HMP ID 1989) is a gingivalis, Strain F0566, HM-1141.” reference genome for The Human Microbiome Project (HMP). HMP is an initiative to identify and characterize Biosafety Level: 2 human microbial flora. -

Compendium of Veterinary Standard Precautions for Zoonotic Disease Prevention in Veterinary Personnel

Compendium of Veterinary Standard Precautions for Zoonotic Disease Prevention in Veterinary Personnel National Association of State Public Health Veterinarians Veterinary Infection Control Committee 2010 Preface.............................................................................................................................................................. 1405 I. INTRODUCTION................................................................................................................................... 1405 A. OBJECTIVES...................................................................................................................................... 1405 B. BACKGROUND................................................................................................................................. 1405 C. CONSIDERATIONS.......................................................................................................................... 1405 II. ZOONOTIC DISEASE TRANSMISSION................................................................................................ 1406 A. SOURCE ............................................................................................................................................ 1406 B. HOST SUSCEPTIBILITY.................................................................................................................... 1406 C. ROUTES OF TRANSMISSION........................................................................................................... 1406 1. CONTACT TRANSMISSION......................................................................................................... -

Recent Advances in Understanding Immunity Against Brucellosis: Application for Vaccine Development

The Open Veterinary Science Journal, 2010, 4, 101-107 101 Open Access Recent Advances in Understanding Immunity Against Brucellosis: Application for Vaccine Development Sérgio Costa Oliveira*,1, Gilson Costa Macedo1, Leonardo Augusto de Almeida1, Fernanda Souza de Oliveira1, Angel Onãte2, Juliana Cassataro3 and 3 Guillermo Hernán Giambartolomei 1Department of Biochemistry and Immunology, Institute of Biological Sciences, Federal University of Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte-Minas Gerais, Brazil 2Department of Microbiology, Faculty of Biological Sciences, Molecular Immunology Laboratory, Universidad de Concepción, Concepción, Chile 3Instituto de Estudios de la Inmunidad Humoral (CONICET), Facultad de Farmacia y Bioquímica, Universidad de Buenos Aires (UBA), Buenos Aires, Argentina Abstract: Brucellosis is an important zoonotic disease of nearly worldwide distribution. This pathogen causes abortion in cattle and undulant fever, arthritis, endocarditis and meningitis in human. The immune response against B. abortus involves innate and adaptive immunity involving antigen-presenting cells, NK cells and CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. IFN- is a crucial immune component that results from Brucella recognition by host immune receptors such as Toll-like receptors (TLRs) that lead to IL-12 production. Although great efforts to elucidate immunity against Brucella have been employed, the subset of cells and factors involved in host immune response remains not completely understood. Our group and others have been working in an attempt to understand the mechanisms involved in innate responses to Brucella. Understanding the requirements for immune protection can help the design of alternative vaccines that would avoid the drawbacks of currently available vaccines to Brucella. This review discusses recent studies in host immunity to Brucella and new approaches for vaccine development. -

Canid, Hye A, Aardwolf Conservation Assessment and Management Plan (Camp) Canid, Hyena, & Aardwolf

CANID, HYE A, AARDWOLF CONSERVATION ASSESSMENT AND MANAGEMENT PLAN (CAMP) CANID, HYENA, & AARDWOLF CONSERVATION ASSESSMENT AND MANAGEMENT PLAN (CAMP) Final Draft Report Edited by Jack Grisham, Alan West, Onnie Byers and Ulysses Seal ~ Canid Specialist Group EARlliPROMSE FOSSIL RIM A fi>MlY Of CCNSERVA11QN FUNDS A Joint Endeavor of AAZPA IUCN/SSC Canid Specialist Group IUCN/SSC Hyaena Specialist Group IUCN/SSC Captive Breeding Specialist Group CBSG SPECIES SURVIVAL COMMISSION The work of the Captive Breeding Specialist Group is made possible by gellerous colltributiolls from the following members of the CBSG Institutional Conservation Council: Conservators ($10,000 and above) Federation of Zoological Gardens of Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum Claws 'n Paws Australasian Species Management Program Great Britain and Ireland BanhamZoo Darmstadt Zoo Chicago Zoological Society Fort Wayne Zoological Society Copenhagen Zoo Dreher Park Zoo Columbus Zoological Gardens Gladys Porter Zoo Cotswold Wildlife Park Fota Wildlife Park Denver Zoological Gardens Indianapolis Zoological Society Dutch Federation of Zoological Gardens Great Plains Zoo Fossil Rim Wildlife Center Japanese Association of Zoological Parks Erie Zoological Park Hancock House Publisher Friends of Zoo Atlanta and Aquariums Fota Wildlife Park Kew Royal Botanic Gardens Greater Los Angeles Zoo Association Jersey Wildlife Preservation Trust Givskud Zoo Miller Park Zoo International Union of Directors of Lincoln Park Zoo Granby Zoological Society Nagoya Aquarium Zoological Gardens The Living Desert Knoxville Zoo National Audubon Society-Research Metropolitan Toronto Zoo Marwell Zoological Park National Geographic Magazine Ranch Sanctuary Minnesota Zoological Garden Milwaukee County Zoo National Zoological Gardens National Aviary in Pittsburgh New York Zoological Society NOAHS Center of South Africa Parco Faunistico "La To:rbiera" Omaha's Henry Doorly Zoo North of Chester Zoological Society Odense Zoo Potter Park Zoo Saint Louis Zoo Oklahoma City Zoo Orana Park Wildlife Trust Racine Zoological Society Sea World, Inc. -

Francisella Tularensis 6/06 Tularemia Is a Commonly Acquired Laboratory Colony Morphology Infection; All Work on Suspect F

Francisella tularensis 6/06 Tularemia is a commonly acquired laboratory Colony Morphology infection; all work on suspect F. tularensis cultures .Aerobic, fastidious, requires cysteine for growth should be performed at minimum under BSL2 .Grows poorly on Blood Agar (BA) conditions with BSL3 practices. .Chocolate Agar (CA): tiny, grey-white, opaque A colonies, 1-2 mm ≥48hr B .Cysteine Heart Agar (CHA): greenish-blue colonies, 2-4 mm ≥48h .Colonies are butyrous and smooth Gram Stain .Tiny, 0.2–0.7 μm pleomorphic, poorly stained gram-negative coccobacilli .Mostly single cells Growth on BA (A) 48 h, (B) 72 h Biochemical/Test Reactions .Oxidase: Negative A B .Catalase: Weak positive .Urease: Negative Additional Information .Can be misidentified as: Haemophilus influenzae, Actinobacillus spp. by automated ID systems .Infective Dose: 10 colony forming units Biosafety Level 3 agent (once Francisella tularensis is . Growth on CA (A) 48 h, (B) 72 h suspected, work should only be done in a certified Class II Biosafety Cabinet) .Transmission: Inhalation, insect bite, contact with tissues or bodily fluids of infected animals .Contagious: No Acceptable Specimen Types .Tissue biopsy .Whole blood: 5-10 ml blood in EDTA, and/or Inoculated blood culture bottle Swab of lesion in transport media . Gram stain Sentinel Laboratory Rule-Out of Francisella tularensis Oxidase Little to no growth on BA >48 h Small, grey-white opaque colonies on CA after ≥48 h at 35/37ºC Positive Weak Negative Positive Catalase Tiny, pleomorphic, faintly stained, gram-negative coccobacilli (red, round, and random) Perform all additional work in a certified Class II Positive Biosafety Cabinet Weak Negative Positive *Oxidase: Negative Urease *Catalase: Weak positive *Urease: Negative *Oxidase, Catalase, and Urease: Appearances of test results are not agent-specific.