Language Use in Longsight

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Q05a 2011 Census Summary

Ward Summary Factsheet: 2011 Census Q05a • The largest ward is Cheetham with 22,562 residents, smallest is Didsbury West with 12,455 • City Centre Ward has grown 156% since 2001 (highest) followed by Hulme (64%), Cheetham (49%), Ardwick (37%), Gorton South (34%), Ancoats and Clayton (33%), Bradford (29%) and Moss Side (27%). These wards account for over half the city’s growth • Miles Platting and Newton Heath’s population has decreased since 2001(-5%) as has Moston (-0.2%) • 81,000 (16%) Manchester residents arrived in the UK between 2001 and 2011, mostly settling in City Centre ward (33% of ward’s current population), its neighbouring wards and Longsight (30% of current population) • Chorlton Park’s population has grown by 26% but only 8% of its residents are immigrants • Gorton South’s population of children aged 0-4 has increased by 87% since 2001 (13% of ward population) followed by Cheetham (70%), Crumpsall (68%), Charlestown (66%) and Moss Side (60%) • Moss Side, Gorton South, Crumpsall and Cheetham have around 25% more 5-15 year olds than in 2001 whereas Miles Platting and Newton Heath, Woodhouse Park, Moston and Withington have around 20-25% fewer. City Centre continues to have very few children in this age group • 18-24 year olds increased by 288% in City Centre since 2001 adding 6,330 residents to the ward. Ardwick, Hulme, Ancoats and Clayton and Bradford have also grown substantially in this age group • Didsbury West has lost 18-24 aged population (-33%) since 2001, followed by Chorlton (-26%) • City Centre working age population has grown by 192% since 2001. -

Buses Serving North Manchester General Hospital

Buses serving North Manchester General Hospital 52 Salford Shopping City, Broughton, Cheetham Hill, NMGH, Harpurhey, Moston, Newton Heath, Failsworth Tesco Bus Stops Daily service, operated by First Greater Manchester A,C, Pendleton Higher Broughton Cheetham Hill NMG Moston Newton Heath Brookdale Failsworth D,E,F Salford Shopping City McDonalds Crescent Road Hospital Ben Brierley Dean Lane Park Tesco Store 27 16 7 12 21 26 32 ______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ 53 Cheetham Hill, NMGH, Harpurhey, Miles Platting, SportCity, Gorton, Belle Vue, Longsight, Rusholme, Central Manchester Bus Stops Hospitals, Hulme, Old Trafford A,C, Daily service, operated by First Greater Manchester D,E,F Cheetham Hill NMG Harpurhey Sport Gorton Belle Rusholme University Old Trafford Salford Crescent Road Hospital Rochdale Rd City Vue of Manchester Trafford Bar Shopping City 7 7 16 31 35 50 58 68 80 _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ 88=> Circulars, Manchester City Centre, Monsall, Moston, White Moss, Blackley, NMGH, Cheetham Hill, Manchester City Centre 89<= Daily service, operated by First Greater Manchester (Evenings, Sundays and Bank Holidays—JPT) Use these buses and change at Crumpsall Metrolink Station or Cheetham Hill, Cheetham Hill Rd (Bus 135) for Bury. Bus Stops Manchester Central Moston White Blackley Bank Crumpsall NMG Cheetham Manchester -

Service Name Teams /Clinics Referrals Accepted from Age Limits

Criteria for this Additional Referral Referrals Referrals Age limits for this service referral format received Contact numbers Service Name Teams /Clinics accepted from service Residence or GP guidance required by Emails must be nhs.net accounts or CMFT to CMFT email only Address Audiology Audiology Professionals 0-18 years Manchester, CYPS referral Post Tel : 0161 232 4214 or 4215 - Audiology Moss Side Health Centre Newborn Hearing Screening Parents/carers Trafford Salford & form Verbal Telephone Tel : 232 1511 - New Born Screening Monton Street Bury residents Fax Fax : 0161 232 4213 Moss Side Email Text : 0787 098 6792 Manchester M14 4GP E-mail - [email protected] Childrens see below Health 0-16 years Manchester CYPS referral E mail Tel: 0161 248 8501 Longsight Health Centre Community professionals 16- 25 years if complex resident form Verbal Telephone Email: [email protected] Stockport Rd, Longsight , Nursing team Lead professionals needs Letter Post Manchester , M13 0RR other organistaions Families known to service Children's Asthma Service GP 6 months-16 yrs Manchester Email Email Tel : 0161 248 1226 Longsight Health Centre School Nurse resident letter Post Fax : 0161 248 6267 Stockport Rd, Longsight , Health Visitor Asthma Nurse Fax Fax E-mail : [email protected] Manchester , M13 0RR Specialist referral Consultants criteria.doc Practice Nurses CCNT Child 1-16yrs Manchester CYPS referral Email Tel: 741 2030 Charlestown Health Centre, Parent Up to 19 if complex resident or form Post Fax:741 2029 Charlestown Road, Blackley. Children's Continence Service Health Care needs Manchester GP Children's Fax Email : [email protected]. -

Victoria Park, Manchester

A SHORT ACCOUNT OF THE VICTORIA PARK, MANCHESTER. Published by the Park Trust Committee in Commemoration of the Centenary of the Opening of the Park on July 31st, 1837. A SHORT ACCOUNT OF THE VICTORIA PARK, MANCHESTER. Published by the Park Trust Committee in Commemoration of the Centenary of the Opening of the Park on July 31st, 1837. 1. Introductory. 2. Formation of the Victoria Park Company. 3. The Victoria Park Act of 1837. 4. The Preparation of the Park. 5. The Opening Ceremony. 6. The Breakdown of the Victoria Park Company and the Formation of the Victoria Park Trust. 7. General Survey of the Trust’s Work, including Minutes, Accounts, Tolls, Buildings and Rates. 8. Absorption of Rusholme by Manchester, 1885. 9. Troubles over Tolls and Building. 10. Development of the Park ; Roads and later Building. 11. Tramway Controversies, 1902 and 1920. 12. Manchester Corporation Act of 1935. 13. Houses, Institutions and Former Residents. 14. Present Situation. Conclusion. 15. List of Officials of the Park. 16. Victoria Park Trust Committee for 1937. 3 I. Introductory. The Victoria Park, Manchester, had its begin nings, partly in a town-planning scheme, which was far ahead of its time, and for which the City may now well be thankful, and partly as a gamble. Of the gamble more will be said shortly. The name was chosen in the reign of William IV, while the Princess Victoria was heiress presumptive to the throne and evidently in honour of the future Queen. The Park arose out of the desire of certain wealthy inhabitants to reside in a quiet area well away from the bustle of their business in Manchester itself. -

Manchester Migration a Profile of Manchester’S Migration Patterns

Manchester Migration A Profile of Manchester’s migration patterns Elisa Bullen Public Intelligence Performance and Intelligence Chief Executive’s Department Date: March 2015 Version 2015/v1.3 www.manchester.gov.uk Introduction ...................................................................................................................................................3 Manchester’s Migration History ..................................................................................................................... 3 International migration trends ................................................................................................................ 3 Internal migration trends ........................................................................................................................4 Household movement ...................................................................................................................................5 Households moving within a ward ......................................................................................................... 8 Households moving from one Manchester ward to another ................................................................... 9 Long-term International Migration ............................................................................................................... 11 Wards popular with recent movers from abroad .................................................................................. 13 Country of birth ................................................................................................................................... -

School Bus Services in Manchester

Effective 1 September 2020 Burnage Academy for Boys 0900 – 1515 The following bus services run close by - details can be found at www.tfgm.com: Stagecoach service 25 – Stockport, Heaton Norris, Heaton Moor, Chorlton, Stretford, Lostock, Davyhulme Stagecoach service 50 – East Didsbury, Chorlton upon Medlock, Manchester, Pendleton, Salford Quays Stagecoach service 171 – Newton Heath, Clayton, Openshaw, Gorton, Ryder Brow, Levenshulme, East Didsbury, Didsbury Stagecoach service 172 – Newton Heath, Clayton, Openshaw, Gorton, Ryder Brow, Levenshulme, West Didsbury Stagecoach service 197 – Stockport, Heaton Moor, Levenshulme, Longsight, Chorlton upon Medlock, Manchester Additionally specific schoolday only services also serve the school as follows: Stagecoach Service 748 – Gorton, Ryder Brow, Levenshulme Stagecoach Service 749 – Whalley Range, Moss Side, Longsight, Levenshulme Stagecoach Service 751 (PM Only) – Chorlton upon Medlock, Manchester Stagecoach Service 797 (PM Only) – Levenshulme, Longsight, Chorlton upon Medlock, Manchester Gorton / Ryder Brow / Levenshulme Service 748 TfGM Contract: 0443 TfGM Contract: 5089 Minimum Capacity: 90 Minimum Capacity: 52 Operator Code: STG Operator Code: BEV Gorton, Tesco 0820 Burnage Academy 1545 Ryder Brow, Station 0824 Levenshulme, Station 1552 Mount Road/Matthews Lane 0828 Mount Road/Matthews Lane 1558 Levenshulme, Station 0835 Ryder Brow, Station 1601 Burnage Academy 0845 Gorton, Tesco 1609 Service 748 route: From Gorton, Tesco via Garratt Way, Whitwell Way, Knutsford Road, Brookhurst Road, Levenshulme -

Geographies of Diversity in Manchester

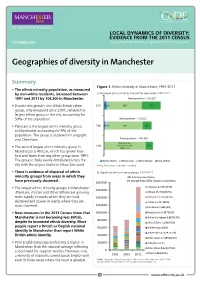

LOCAL DYNAMICS OF DIVERSITY: EVIDENCE FROM THE 2011 CENSUS OCTOBER 2013 Prepared by ESRC Centre on Dynamics of Ethnicity (CoDE) Geographies of diversity in Manchester Summary Figure 1. Ethnic diversity in Manchester, 1991-2011 • The ethnic minority population, as measured by non-white residents, increased between a) Increased ethnic minority share of the population, 1991-2011 1991 and 2011 by 104,300 in Manchester. Total population – 503,127 • Despite this growth, the White British ethnic 2011 5% 2% 59% 33% group, only measured since 2001, remains the largest ethnic group in the city, accounting for 59% of the population. Total population – 422,922 • Pakistani is the largest ethnic minority group 2001 2% 4% 74% 19% in Manchester accounting for 9% of the population. The group is clustered in Longsight and Cheetham. Total population – 432,685 85% (includes 1991 White Other and 15% • The second largest ethnic minority group in White Irish Manchester is African, which has grown four- fold and faster than any other group since 1991. The group is fairly evenly distributed across the White Other White Irish White British Non-White city with the largest cluster in Moss Side ward. Notes: Figures may not add due to rounding. • There is evidence of dispersal of ethnic b) Growth of ethnic minority groups, 1991-2011 minority groups from areas in which they 2011 Census estimates (% change from 2001 shown in brackets): have previously clustered. 180,000 • The largest ethnic minority groups in Manchester Pakistani 42,904 (73%) 160,000 (Pakistani, African and Other White) are growing African 25,718 (254%) more rapidly in wards where they are least 140,000 Chinese 13,539 (142%) clustered and slower in wards where they are Indian 11,417 (80%) 120,000 most clustered. -

Ardwick Exhibition Size 3 MB

-of~6ij disabledlition people GMCDP Introduction: In 2006 Greater Manchester Coalition of Disabled People ran a project to record the experiences and memories of Deaf and Disabled People from Ardwick, Manchester. The history of people's everyday lives is often overlooked when past experiences are recorded. However, the lives of deaf and disabled people are almost totally ignored and largely undocumented. The Ardwick People's History Project aims to change this and the exhibition is part our contribution to that process. The following panels are selected extracts from the interviews we conducted over the summer. Acknowledgement.: Brenda I Harbert, Laa, Sheila, Taddy, C•• , Kenny. and Audrey Additional thanks: Pablck Burke, Brian Kokoruwe and Manchester City Council's Archives and Local Studies Department (photographs reproduced by kind pennission of Manchutar City Council). Further Information From: GMCDP, Aked Close, Ardwick, Manchester M12 4AN Tel: 0161 273 5154 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www. gmcdp.com Funded by: Additional Support from: • • • .. ESF" •• LK : • • • ~ MANCHESTER a EUROPEAN U N ION C ' T Y COU N C i l EU<OpNn SocIoI Fur"d ENG LI SH HERIT AG E Audrey (Born 1951) Regeneration: where I was living , where all the houses were pulled down ... for regeneration ... they built... a block of flats ... called Fort Ardwick ... it didn't work .... they eventually pulled all those flats down and ... built houses there. So really over the last.... thirty five years, you'd gone from bringing house down here to putting up flats to taking them down and another regeneration gone on ... Special Schools: when I was at Thomas' Street School .. -

Healthy Me Healthy Communities Services for Central

0 G A T A N O C COMPILED BY R O G AT N S I MANCHESTER S T BESWICK 5 3 6 A63 MILES 5 ASHTON OLD R A PLATTING OAD Old Abbey Taphouse COMMUNITY GROCER* Hulme Community Hub offering hot meals A57(M) WEST Anson Cabin Project and Anson & necessity deliveries, newsletter, radio GORTON A Ardwick 50 COMMUNITY Childrens ARDWICK Community House (also hosts HMHC Grab & Go) Hulme 6 GORTON GROCER* station & live streaming, befriending service. 7 C Centre H Abbey Hey Lane i COVERDALE h g Park Zion Community h & NEWBANK Providing support and activities for children, o e r A G Resource Centre C COMMUNITY orto r n Contact: Rachele 07905271883 Martenscroft a La l Childrens m 3 GROCER* ne to O b young people and adults of all ages. Centre r 4 Z Arts i d x or Craig 07835166295 n g e fo Road S t r Ardwick Contact: 0161 248 569 or Trinity Sports d Sports Hall [email protected] L Leisure A 4 l o HULME P R A 57A57 y e d Aquarius n o HY [email protected] 6 HULME c S H Centre r a t Moss Side o DY COMMUNITY r d Gorton South Gorton ED e f Leisure Centre 3 t BELLE E Guildhall Close, Manchester Science Park e Active RD GROCER* Childrens Sacred Heart www.ansoncabin.co.uk t R W Lifestyles OA N Centre Childrens a y o Centre Centre Y r t Kath Locke VUE h 1 M15 6SY Centre A Meldon Road, Manchester M13 0TT oss L M a n e Ea A s M t W Whitworth o N u MOSS n K Park t S Gorton Day Centre R R o Moss L ane East O Pakistani a Levenshulme Inspire d SIDE Rusholme Community A N Childrens Moss Side Age UK Centre Food parcels, shopping and prescription P Centre Powerhouse U R Meal deliveries, wellbeing support and p O p LONGSIGHT S e deliveries, and wellbeing support. -

'After Housing Costs' Child Poverty Rate from Highest to Lowest

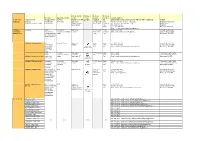

Notes: This spreadsheet ranks wards in Greater Manchester by their 'after housing costs' child poverty rate from highest to lowest. This is done using data published by End Child Poverty in 2019. The data also ranks areas based on the proportion of the population in a ward classified as black and minority ethnic (BAME) in census data. The higher the proportion of people who are BAME in a ward the higher the rank. This data shows that areas with the highest BAME populations in Greater Manchester are often the areas with the highest rates of child poverty. Local Ward GM Child poverty rank GM BAME authority area (after housing costs) rank Oldham Werneth 1 1 Oldham St Mary's 2 6 Oldham Coldhurst 3 3 Manchester Longsight 4 4 Salford Ordsall 5 48 Manchester Cheetham 6 9 Rochdale Central Rochdale 7 10 Manchester Hulme 8 16 Rochdale Milkstone and Deeplish 9 2 Manchester Gorton South 10 17 Rochdale Kingsway 11 23 Salford Broughton 12 47 Bolton Great Lever 13 13 Manchester Rusholme 14 11 Salford Kersal 15 82 Oldham Alexandra 16 25 Oldham Medlock Vale 17 22 Salford Irwell Riverside 18 55 Manchester Crumpsall 19 15 Manchester Ardwick 20 12 Manchester Bradford 21 29 Manchester Miles Platting and Newton Heath 22 52 Tameside St Peter's 23 30 Bolton Rumworth 24 7 Salford Langworthy 25 72 Manchester Gorton North 26 27 Bury Sedgley 27 56 Bolton Harper Green 28 37 Bolton Halliwell 29 20 Manchester Ancoats and Clayton 30 40 Rochdale Smallbridge and Firgrove 31 36 Manchester Levenshulme 32 18 Trafford Clifford 33 8 Manchester Moss Side 34 5 Manchester Fallowfield -

Unit 1-3 Ladybarn House Moseley Road Fallowfield Manchester M14 6ND

Unit 1-3 Ladybarn House Moseley Road Fallowfield Manchester M14 6ND Tel: 0161 275 7682 [email protected] www.manchthesters tdthtudenthomes.com Who we are • We are owned and managed by the University of Manchester and Manchester Metropolitan University • Non-profit • Housing advice to students • A Lan dlord A ccredit a tion Sc heme - Landlords commit to a Code of Standards - Complaints process - Mediate in disputes - Withdraw services and accreditation when code is seriously or continuously breached Our Homes We advertise all our properties at www.mancehsterstudenthomes.com • Range of properties from rooms in private halls to 9 and 10 bed houses • Rent from £40 to £100 per week - depends on location and quality - Sometime utilities included • In all major student areas and elsewhere • Advertising for 2011/12 • ShbtSearch by type, area, si ze and di price • Deal directly with the landlord to arrange viewings and to sign up • NfNo agency fees, accre ditdtdldldthlifdited property and landlord, extra help if something does wrong House Huntinggp Tips • Get your whole group together for each viewing • Get a number of viewings in one ago • Where is the ppproperty ? How do y ou g et there? How long does it take to get from one place to another? • Be very observant • “Buyer Beware” in most cases • Find out as much as you can • Once you sign up its too late • No shortage of 3,4 & 5 bedroom houses • Don’t be afraid to negotiate • Later in the year you may strike a better deal • Explore the city! Manchester: Area by Area 3 Withington 2. -

Roma Community Cohesion Project Evaluation 2012

Roma Community Cohesion Project Evaluation 2012 Roma Community Cohesion Project In January 2007 European Economic Area nationals behaviour in the area. A number of public meetings were The Big Issue in the North grew until, in 2011, 40% of became able to move and reside freely in any held and attended by a vocal section of the community vendors were of Roma origin. EU member state. Around this time, increasing and local ward councillors, where anger was directed The Roma Community Cohesion project worked numbers of Roma (from countries like Romania) at the Roma community. At the same time the Roma in partnership with local organisations, schools, began to settle in a concentrated area of private community were negatively portrayed in a number of Manchester University, Manchester City Council, the rented accommodation in South Gorton. articles in national and local press. Police and health services to: By 2010, Longsight Children’s Centre were working In response, in 2010/11, The Big Issue in the North Trust • Create role models in the Roma community to widen with small numbers of the Roma families and identified provided £50,000 funding for the Roma Community opportunities that many families were living in poverty with issues Cohesion project in the Longsight Children’s Centre. including overcrowding, lack of basic furniture, lack of • Improve access to services by Roma people The Big Issue in the North had already had experience access to health services or training and employment of working Roma people. Opportunities for Roma to earn • Build greater understanding between the Roma advice, and a lack of school places for children.