The Division and Order of the Psalms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notes on Psalms 2015 Edition Dr

Notes on Psalms 2015 Edition Dr. Thomas L. Constable Introduction TITLE The title of this book in the Hebrew Bible is Tehillim, which means "praise songs." The title adopted by the Septuagint translators for their Greek version was Psalmoi meaning "songs to the accompaniment of a stringed instrument." This Greek word translates the Hebrew word mizmor that occurs in the titles of 57 of the psalms. In time the Greek word psalmoi came to mean "songs of praise" without reference to stringed accompaniment. The English translators transliterated the Greek title resulting in the title "Psalms" in English Bibles. WRITERS The texts of the individual psalms do not usually indicate who wrote them. Psalm 72:20 seems to be an exception, but this verse was probably an early editorial addition, referring to the preceding collection of Davidic psalms, of which Psalm 72 was the last.1 However, some of the titles of the individual psalms do contain information about the writers. The titles occur in English versions after the heading (e.g., "Psalm 1") and before the first verse. They were usually the first verse in the Hebrew Bible. Consequently the numbering of the verses in the Hebrew and English Bibles is often different, the first verse in the Septuagint and English texts usually being the second verse in the Hebrew text, when the psalm has a title. ". there is considerable circumstantial evidence that the psalm titles were later additions."2 However, one should not understand this statement to mean that they are not inspired. As with some of the added and updated material in the historical books, the Holy Spirit evidently led editors to add material that the original writer did not include. -

Psalms Psalm

Cultivate - PSALMS PSALM 126: We now come to the seventh of the "Songs of Ascent," a lovely group of Psalms that God's people would sing and pray together as they journeyed up to Jerusalem. Here in this Psalm they are praying for the day when the Lord would "restore the fortunes" of God's people (vs.1,4). 126 is a prayer for spiritual revival and reawakening. The first half is all happiness and joy, remembering how God answered this prayer once. But now that's just a memory... like a dream. They need to be renewed again. So they call out to God once more: transform, restore, deliver us again. Don't you think this is a prayer that God's people could stand to sing and pray today? Pray it this week. We'll pray it together on Sunday. God is here inviting such prayer; he's even putting the very words in our mouths. PSALM 127: This is now the eighth of the "Songs of Ascent," which God's people would sing on their procession up to the temple. We've seen that Zion / Jerusalem / The House of the Lord are all common themes in these Psalms. But the "house" that Psalm 127 refers to (in v.1) is that of a dwelling for a family. 127 speaks plainly and clearly to our anxiety-ridden thirst for success. How can anything be strong or successful or sufficient or secure... if it does not come from the Lord? Without the blessing of the Lord, our lives will come to nothing. -

Psalms, Hymns, and Spiritual Songs: the Master Musician's Melodies

Psalms, Hymns, and Spiritual Songs: The Master Musician’s Melodies Bereans Sunday School Placerita Baptist Church 2006 by William D. Barrick, Th.D. Professor of OT, The Master’s Seminary Psalm 66 — Universal Praise 1.0 Introducing Psalm 66 y “Within the context of the group of Psalms 56–68, Psalm 66 (along with its companion piece, Ps. 67) offers a fitting litany of universal praise of God for his ‘awesome deeds’ (66:3a) and power.”—Gerald H. Wilson, Psalms Volume 1, NIV Application Commentary (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Zondervan, 2002), 915. y Psalms 66 and 67 are not attributed to any specific author. 9 Psalms 66 and 67 are the only anonymous psalms in Book 2 (Psalms 42–72). 9 The first non-Davidic psalms since Psalm 50. 9 The only anonymous psalms prior to this are Psalms 1, 2, and 33. y “A Song” in the headings of Psalms 62–68 links them together in a group. (See additional similarities among these psalms in the notes on Psalm 65.) y Several commentators (e.g., Perowne, Wilcock) believe that the setting for this psalm might be in the time of Hezekiah. 9 God miraculously delivered Jerusalem from the Assyrians (Isaiah 37). 9 God miraculously healed Hezekiah (Isaiah 38). 9 Hezekiah wrote a psalm then (Isaiah 38:9-20), perhaps he also wrote Psalm 66. 2.0 Reading Psalm 66 (NAU) 66:1 A Song. A Psalm. Shout joyfully to God, all the earth; 66:2 Sing the glory of His name; Make His praise glorious. 66:3 Say to God, “How awesome are Your works! Because of the greatness of Your power Your enemies will give feigned obedience to You. -

The Book of Alternative Services of the Anglican Church of Canada with the Revised Common Lectionary

Alternative Services The Book of Alternative Services of the Anglican Church of Canada with the Revised Common Lectionary Anglican Book Centre Toronto, Canada Copyright © 1985 by the General Synod of the Anglican Church of Canada ABC Publishing, Anglican Book Centre General Synod of the Anglican Church of Canada 80 Hayden Street, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4Y 3G2 [email protected] www.abcpublishing.com All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher. Acknowledgements and copyrights appear on pages 925-928, which constitute a continuation of the copyright page. In the Proper of the Church Year (p. 262ff) the citations from the Revised Common Lectionary (Consultation on Common Texts, 1992) replace those from the Common Lectionary (1983). Fifteenth Printing with Revisions. Manufactured in Canada. Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data Anglican Church of Canada. The book of alternative services of the Anglican Church of Canada. Authorized by the Thirtieth Session of the General Synod of the Anglican Church of Canada, 1983. Prepared by the Doctrine and Worship Committee of the General Synod of the Anglican Church of Canada. ISBN 978-0-919891-27-2 1. Anglican Church of Canada - Liturgy - Texts. I. Anglican Church of Canada. General Synod. II. Anglican Church of Canada. Doctrine and Worship Committee. III. Title. BX5616. A5 1985 -

Psalm 99 and Mark Every Reference to the LORD Speaking I.E

PSALMS - The SONGS Ninety-Nine Exalt and Worship the Holy Reigning LORD at His Holy Hill! READ AND OBSERVE Read through Psalm 99 and mark every reference to the LORD speaking i.e. the mouth of the Lord, instruction of our God, vision of God, declares, etc. Highlight the word or phrase in yellow and then circle all that you have highlighted in red. Words such as testimonies and statutes would be pronouns in this particular instance. Read through Psalm 99 and mark every reference to the Glory of the LORD, or the Name of the LORD. Highlight the word or phrase in light purple and put a yellow box around all that you have highlighted. Read through Psalm 99 and mark every reference to the word exalt with an upward purple cloud around the word. Read through Psalm 99 and mark every reference to the word Holy. Highlight the word or phrase in pink and put a blue box around all that you have highlighted. Read through Psalm 99 and mark every reference to called (when the people are calling on the Name of God) with a blue upward arrow. Read through Psalm 99 and underline every reference to worshiping the LORD in brown. Read through Psalm 99 and mark every reference to righteousness with a blue capital “R+”. Read through Psalm 99 and mark every reference to justice with a purple capital “J”. Read through Psalm 99 and mark every reference to Zion or Jerusalem with a blue capital “Z”. This can include pronouns such as you and sanctuary. -

Weekly Spiritual Fitness Plan” but the Basic Principles of Arrangement Seem to Be David to Provide Music for the Temple Services

Saturday: Psalms 78-82 (continued) Monday: Psalms 48-53 81:7 “I tested you.” This sounds like a curse. Yet it FAITH FULLY FIT Psalm 48 This psalm speaks about God’s people, is but another of God’s blessings. God often takes the church. God’s people are symbolized by Jerusa- something from us and then waits to see how we My Spiritual Fitness Goals for this week: Weekly Spiritual lem, “the city of our God, his holy mountain . will handle the problem. Will we give up on him? Mount Zion.” Jerusalem refers to the physical city Or will we patiently await his intervention? By do- where God lived among his Old Testament people. ing the latter, we are strengthened in our faith, and But it also refers to the church on earth and to the we witness God’s grace. Fitness Plan heavenly, eternal Jerusalem where God will dwell among his people into eternity. 82:1,6 “He gives judgment among the ‘gods.’” The designation gods is used for rulers who were to Introduction & Background 48:2 “Zaphon”—This is another word for Mount represent God and act in his stead and with his to this week’s readings: Hermon, a mountain on Israel’s northern border. It authority on earth. The theme of this psalm is that was three times as high as Mount Zion. Yet Zion they debased this honorific title by injustice and Introduction to the Book of Psalms - Part 3 was just as majestic because the great King lived corruption. “God presides in the great assembly.” within her. -

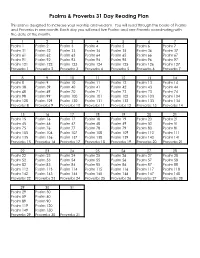

Psalms & Proverbs 31 Day Reading Plan

Psalms & Proverbs 31 Day Reading Plan This plan is designed to increase your worship and wisdom. You will read through the books of Psalms and Proverbs in one month. Each day you will read five Psalms and one Proverb coordinating with the date of the month. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Psalm 1 Psalm 2 Psalm 3 Psalm 4 Psalm 5 Psalm 6 Psalm 7 Psalm 31 Psalm 32 Psalm 33 Psalm 34 Psalm 35 Psalm 36 Psalm 37 Psalm 61 Psalm 62 Psalm 63 Psalm 64 Psalm 65 Psalm 66 Psalm 67 Psalm 91 Psalm 92 Psalm 93 Psalm 94 Psalm 95 Psalm 96 Psalm 97 Psalm 121 Psalm 122 Psalm 123 Psalm 124 Psalm 125 Psalm 126 Psalm 127 Proverbs 1 Proverbs 2 Proverbs 3 Proverbs 4 Proverbs 5 Proverbs 6 Proverbs 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Psalm 8 Psalm 9 Psalm 10 Psalm 11 Psalm 12 Psalm 13 Psalm 14 Psalm 38 Psalm 39 Psalm 40 Psalm 41 Psalm 42 Psalm 43 Psalm 44 Psalm 68 Psalm 69 Psalm 70 Psalm 71 Psalm 72 Psalm 73 Psalm 74 Psalm 98 Psalm 99 Psalm 100 Psalm 101 Psalm 102 Psalm 103 Psalm 104 Psalm 128 Psalm 129 Psalm 130 Psalm 131 Psalm 132 Psalm 133 Psalm 134 Proverbs 8 Proverbs 9 Proverbs 10 Proverbs 11 Proverbs 12 Proverbs 13 Proverbs 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 Psalm 15 Psalm 16 Psalm 17 Psalm 18 Psalm 19 Psalm 20 Psalm 21 Psalm 45 Psalm 46 Psalm 47 Psalm 48 Psalm 49 Psalm 50 Psalm 51 Psalm 75 Psalm 76 Psalm 77 Psalm 78 Psalm 79 Psalm 80 Psalm 81 Psalm 105 Psalm 106 Psalm 107 Psalm 108 Psalm 109 Psalm 110 Psalm 111 Psalm 135 Psalm 136 Psalm 137 Psalm 138 Psalm 139 Psalm 140 Psalm 141 Proverbs 15 Proverbs 16 Proverbs 17 Proverbs 18 Proverbs 19 Proverbs 20 Proverbs 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 Psalm 22 Psalm 23 Psalm 24 Psalm 25 Psalm 26 Psalm 27 Psalm 28 Psalm 52 Psalm 53 Psalm 54 Psalm 55 Psalm 56 Psalm 57 Psalm 58 Psalm 82 Psalm 83 Psalm 84 Psalm 85 Psalm 86 Psalm 87 Psalm 88 Psalm 112 Psalm 113 Psalm 114 Psalm 115 Psalm 116 Psalm 117 Psalm 118 Psalm 142 Psalm 143 Psalm 144 Psalm 145 Psalm 146 Psalm 147 Psalm 148 Proverbs 22 Proverbs 23 Proverbs 24 Proverbs 25 Proverbs 26 Proverbs 27 Proverbs 28 29 30 31 Psalm 29 Psalm 30 Psalm 59 Psalm 60 Psalm 89 Psalm 90 Psalm 119 Psalm 120 Psalm 149 Psalm 150 Proverbs 29 Proverbs 30 Proverbs 31. -

2 Samuel & 1 Chronicles with Associated Psalms

2 Samuel& 1 Chronicles w/Associated Psalms (Part 2 ) -Psalm 22 : The Psalm on the Cross . This anguished prayer of David was on the lips of Jesus at his crucifixion. Jesus’ prayed the psalms on the cross! Also, this is the most quoted psalm in the New Testament. Read this and then pray this the next time you experience anguish. -Psalm 23 : The Shepherd Psalm . Probably the best known psalm among Christians today. -Psalm 24 : The Christmas Processional Psalm . The Christmas Hymn, “Lift Up Your Heads, Yet Might Gates” is based on this psalm; also the 2000 chorus by Charlie Hall, “Give Us Clean Hands.” -Psalm 47 : God the Great King . Several hymns & choruses are based on this short psalmcelebrating God as the Great King over all. Think of “Psalms” as “Worship Hymns/Songs.” -Psalm 68 : Jesus Because of Hesed . Thematically similar to Psalms 24, 47, 132 on the triumphant rule of Israel’s God, with 9 stanzas as a processional liturgy/song: vv.1-3 (procession begins), 4-6 (benevolent God), 7-10 (God in the wilderness [bemidbar]), 11-14 (God in the Canaan conquest), 15-18 (the Lord ascends to Mt. Zion), 19-23 (God’s future victories), 24-27 (procession enters the sanctuary), 28-31 (God subdues enemies), 32-35 (concluding doxology) -Psalm 89 : Davidic Covenant (Part One) . Psalms 89 & 132 along with 2 Samuel 7 & 1 Chronicles 17 focus on God’s covenant with David. This psalm mourns a downfall in the kingdom, but clings to the covenant promises.This psalm also concludes “book 4” of the psalter. -

Wisdom Editing in the Book of Psalms: Vocabulary, Themes, and Structures Steven Dunn Marquette University

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Dissertations (2009 -) Dissertations, Theses, and Professional Projects Wisdom Editing in the Book of Psalms: Vocabulary, Themes, and Structures Steven Dunn Marquette University Recommended Citation Dunn, Steven, "Wisdom Editing in the Book of Psalms: Vocabulary, Themes, and Structures" (2009). Dissertations (2009 -). Paper 13. http://epublications.marquette.edu/dissertations_mu/13 Wisdom Editing in the Book of Psalms: Vocabulary, Themes, and Structures By Steven Dunn, B.A., M.Div. A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School, Marquette University, in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Milwaukee, Wisconsin December 2009 ABSTRACT Wisdom Editing in the Book of Psalms: Vocabulary, Themes, and Structures Steven Dunn, B.A., M.Div. Marquette University, 2009 This study examines the pervasive influence of post-exilic wisdom editors and writers in the shaping of the Psalter by analyzing the use of wisdom elements—vocabulary, themes, rhetorical devices, and parallels with other Ancient Near Eastern wisdom traditions. I begin with an analysis and critique of the most prominent authors on the subject of wisdom in the Psalter, and expand upon previous research as I propose that evidence of wisdom influence is found in psalm titles, the structure of the Psalter, and among the various genres of psalms. I find further evidence of wisdom influence in creation theology, as seen in Psalms 19, 33, 104, and 148, for which parallels are found in other A.N.E. wisdom texts. In essence, in its final form, the entire Psalter reveals the work of scribes and teachers associated with post-exilic wisdom traditions or schools associated with the temple. -

TREASURES of the DEEP: the Unreachable Holiness of God Week 3 PROPS: 10 Commandments in Frame; Hammer; String/Yarn; Flash-A-Card (Moses)

TREASURES OF THE DEEP: The Unreachable Holiness of God Week 3 PROPS: 10 Commandments in Frame; hammer; String/Yarn; Flash-A-Card (Moses) TWO WEEKS AGO: THE DEEP WISDOM OF GOD – WEEK 1 Romans 11:33 O the depth (profound) of the riches both of the wisdom and knowledge of God! how unsearchable (unexplored) are his judgments (decisions), and his ways (roads; paths) past finding out (untraceable; not tracked out)! [SLIDE 2] The Wisdom of Man vs. The Wisdom of God [SLIDE 3] Solomon’s Wisdom ended in Vanity & Jesus’ Wisdom ends in Eternal Life [SLIDE 3] Riches, Works, Success/Fame, Pleasure, Possessions, Wisdom Conclusion: Solomon was looking for FULFILLMENT in LIFE on this EARTH…ANY FULFILLMENT THAT WE FIND ON THIS EARTH WILL BE TEMPORARY…VANITY! Jesus lived his life totally committed to fulfilling the WILL of His Father…therefore, he lived His life with ETERNAL LIFE as the focus! This may seem like foolishness in this life, but, in light of DEATH & ETERNITY, it is the WISDOM of GOD! LAST WEEK: THE PERSISTENT LOVE OF GOD – WEEK 2 Romans 8:39 Nor height, nor depth, nor any other creature, shall be able to separate us from the LOVE OF GOD, which is IN Christ Jesus our Lord. [SLIDE 5] • “separate” - chōrizō (kho-rid'-zo) to place room between, that is, part; reflexively to go away o Matthew 19:6b ...What therefore God hath joined together, let not man put asunder. • MANY THINGS may TRY to separate us from God’s LOVE, but IT CAN’T! If we are IN Jesus Christ, GOD LOVES US! MAN’S HEART OF SIN; THE NEED TO REPENT – turn away from sin and turn to GOD -

Small Group Guide PSALMS 92, 99, & 100 the Church at Brook Hills June 15, 2014 Psalms 92, 99, & 100

Small Group Guide PSALMS 92, 99, & 100 The Church at Brook Hills June 15, 2014 Psalms 92, 99, & 100 Use this resource as a tool to help Christ-followers move forward in their spiritual growth. To do this well requires that the Small Group Leader is building a relationship with the individuals in the small group and has identified where the people are in their relationship with God. Are they Christ- followers? Are they growing in Christ? If so, in what areas do they need to grow further? As disciple- makers, Small Group Leaders shepherd people to know the truth of Scripture, to understand why it matters, and to apply it to their lives. Small Group Leaders come alongside those whom they disciple to discover how loving God, loving each other, and loving those not yet in the Kingdom should shape how they live. The structure of this resource coincides with moving people from knowledge to understanding to application. Utilize this Small Group Guide as a flexible teaching tool to inform your time together and not as a rigid task list. GETTING STARTED Before Small Group Readings for June 16-22 Deuteronomy 21:1-28:19, and Psalm 108:1-119:24 Where We Are In The Story (Deuteronomy) Background of Deuteronomy: Deuteronomy picks up with Moses’ word from the Lord to the Israelites at Mount Horeb at the end of their forty years of wilderness wanderings. Deuteronomy presents the Law (much of what is in Exodus, Leviticus, and Numbers) in a preached format, and it contains three of Moses’ sermons to the people of Israel that both rehearse their history and instruct them in how they are to live as God’s people in the Land of Promise. -

Fr. Lazarus Moore the Septuagint Psalms in English

THE PSALTER Second printing Revised PRINTED IN INDIA AT THE DIOCESAN PRESS, MADRAS — 1971. (First edition, 1966) (Translated by Archimandrite Lazarus Moore) INDEX OF TITLES Psalm The Two Ways: Tree or Dust .......................................................................................... 1 The Messianic Drama: Warnings to Rulers and Nations ........................................... 2 A Psalm of David; when he fled from His Son Absalom ........................................... 3 An Evening Prayer of Trust in God............................................................................... 4 A Morning Prayer for Guidance .................................................................................... 5 A Cry in Anguish of Body and Soul.............................................................................. 6 God the Just Judge Strong and Patient.......................................................................... 7 The Greatness of God and His Love for Men............................................................... 8 Call to Make God Known to the Nations ..................................................................... 9 An Act of Trust ............................................................................................................... 10 The Safety of the Poor and Needy ............................................................................... 11 My Heart Rejoices in Thy Salvation ............................................................................ 12 Unbelief Leads to Universal