Wilderness and the Paradox of Individual Freedom

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WOMEN'sspring 2016

WOMEN’S Spring 2016 RUGGED HEART CONTENTS 05 OUTERWEAR 13 TOPS 21 BOTTOMS 27 ACCESSORIES Style Number Reference Style # Page # Outerwear WJ130 9 Sandstone Active Jac WJ141 10 Sandstone Sierra Jacket WV001 11 Sandstone Mock Neck Vest 100657 11 Sandstone Berkley Jacket 100815 11 Weathered Duck Wildwood Jacket 101046 12 Zeeland Sandstone Bib Overall 101105 8 Force Equator Jacket New Color 101111 7 Mountrail Jacket New Color 101216 10 Camo Active Jac 101409 7 Cascade Jacket New Color 101586 7 Rockford Windbreaker New Color 101732 10 Sandstone Active Jac / Camo Lined 101983 8 El Paso Utility Vest New 101984 9 El Paso Utility Vest / Camo New 101988 8 El Paso Utility Jacket New 102037 9 Brewster Denim Jacket New Style # Page # Tops 100336 15 Calumet V-Neck T-Shirt New Color 100338 15 Calumet Long-Sleeve Crewneck T-Shirt New Color 100434 14 Force Performance T-Shirt New Color 100438 14 Force Performance Tank New Color 100440 15 Force Performance Quarter-Zip Shirt New Color 100704 18 Clarksburg Zip-Front Sweatshirt New Color 100705 19 Clarksburg Quarter-Zip Sweatshirt New Color 100706 19 Dunlow Sweatshirt 101424 18 Hayward Zip-Front Hoodie New Color 101433 18 Clarksburg Camo Zip-Front Sweatshirt Page 2 www.carhartt.com Carhartt Customer Service 1-800-358-3825 Style Number Reference Style # Page # Tops (Continued) 101539 17 Coleharbor Hoodie New Color 102013 16 Signature T-Shirt New 102036 16 Script Logo T-Shirt New 102058 16 Reagan Henley New 102065 17 Coleharbor Hoodie/Printed New 102066 14 Force Performance T-Shirt / Striped New 102069 19 Huron -

Complete List of Member Benefits (Pdf)

Ohio Farm Bureau members Being an Ohio Farm Bureau member really pays! enjoy these savings As a member you can receive all of these great savings. VISIT US ONLINE AT OFBF.ORG/SAVINGS New Benefits NEW! Equipment Bush Hog Ford Bush Hog and Ohio Farm Bureau have partnered together to offer Farm Bureau members Members receive $500 Ford Bonus Cash a $250 discount off the purchase of a Bush Hog product valued at $5,000 or greater. The on the purchase or lease of qualifying products include select agricultural, landscape and construction implements. The discount Ford trucks. is available through authorized Bush Hog dealers and may be redeemed by providing a current Ohio Farm Bureau membership card and ID number to the dealer at the time of purchase. John Deere Rewards OFBF members receive a free two-year Grasshopper Platinum 1 membership. Through this Grasshopper and Ohio Farm Bureau have partnered together to offer members a 15% savings off MSRP special program, members are eligible to on purchases of new mowers and on accessories and implements if purchased at the time of sale of the receive discounts up to $1,700 off select categories of John Deere mower. Benefits also include freight allowance for shipment to dealer location and free setup. equipment. Caterpillar OFBF members can save up to $5,000 when Travel & Entertainment buying or leasing qualifying equipment. Amusement Park Tickets Choice Hotels Negotiate the best deal with a CAT dealer and then add the Farm Discounted tickets for Dollywood, Newport Aquarium, Receive up to 20% off best available Bureau member incentive to the bottom line. -

The Development and Use of Bib Overalls in the United States, 1856-1945 Ann Revenaugh Hemken Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1993 The development and use of bib overalls in the United States, 1856-1945 Ann Revenaugh Hemken Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the American Material Culture Commons, Fashion Business Commons, Fashion Design Commons, and the Other History Commons Recommended Citation Hemken, Ann Revenaugh, "The development and use of bib overalls in the United States, 1856-1945 " (1993). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 337. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/337 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The development and use of bib overalls in the United States, 1856-1945 by Ann Revenaugh Hemken A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Department: Textiles and Clothing Major: Textiles and Clothing Signatures have been redacted for privacy Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 1993 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES................................................ iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS. • • • • • • . • • • • • • • • • • . • • • . • • • • • • • • • • • • • . • • • • • • • . • •• i v INTRODUCTION -

Tracking Corporate Accountability in the Apparel Industry

Tracking Corporate Accountability in the Apparel Industry Updated August 3, 2015 COMPANY COUNTRY BANGLADESH ACCORD SIGNATORY FACTORY TRANSPARENCY COMPENSATION FOR TAZREEN FIRE VICTIMS COMPENSATION FOR RANA PLAZA VICTIMS BRANDS PARENT COMPANY NEWS/ACTION Cotton on Group Australia Y Designworks Clothing Company Australia Y Republic, Chino Kids Forever New Australia Y Kathmandu Australia K-Mart Australia Australia Y Licensing Essentials Pty Ltd Australia Y Pacific Brands Australia Y Pretty Girl Fashion Group Pty Australia Y Speciality Fashions Australia Australia Y Target Australia Australia Y The Just Group Australia Woolworths Australia Australia Y Fashion Team HandelsgmbH Austria Y Paid some initial relief and C&A Foundation has committed to pay a Linked to Rana Plaza. C&A significant amount of Foundation contributed C&A Belgium Y compensation. $1,000,000 to the Trust Fund. JBC NV Belgium Y Jogilo N.V Belgium Y Malu N.V. Belgium Y Tex Alliance Belgium Y Van Der Erve Belgium Y Brüzer Sportsgear LTD Canada Y Canadian Tire Corporation Ltd Canada Giant Tiger Canada Discloses cities of supplier factories, but not full Anvil, Comfort Colors, Gildan, Gold Toe, Gildan Canada addresses. TM, Secret, Silks, Therapy Plus Contributed an undisclosed amount to the Rana Plaza Trust Hudson’s Bay Company Canada Fund via BRAC USA. IFG Corp. Canada Linked to Rana Plaza. Contributed $3,370,620 to the Loblaw Canada Y Trust Fund. Joe Fresh Lululemon Athletica inc. Canada Bestseller Denmark Y Coop Danmark Denmark Y Dansk Supermarked Denmark Y DK Company Denmark Y FIPO China, FIPOTEX Fashion, FIPOTEX Global, Retailers Europe, FIPO Group Denmark Y Besthouse Europe A/S IC Companys A/S Denmark Y Linked to Rana Plaza. -

MICHIGAN STRATEGIC FUND BOARD DRAFT MEETING AGENDA SEPTEMBER 27, 2016 10:00 Am

MICHIGAN STRATEGIC FUND BOARD DRAFT MEETING AGENDA SEPTEMBER 27, 2016 10:00 am Public comment – Please limit public comment to three (3) minutes Communications A. Consent Agenda Proposed Meeting Minutes – August 23, 2016 Zeeland Bio-Based Products, LLC – Loan Settlement – Christin Armstrong Focus Mold & Machining, Inc. – Tool & Die Recovery Zone Revocation – Dan Parisian CNC Precision Machining, LLC – Tool & Die Recovery Zone Revocation – Dan Parisian Plas-Tech Mold & Design, Inc. – Tool & Die Recovery Zone Revocation – Dan Parisian Downtown Albion Hotel/City of Albion – MCRP/Act 381 Work Plan Re-approval – Mary Kramer 618 South Main LLC/City of Ann Arbor – MCRP Amendment – Mary Kramer River Parc Place II, LLC/City of Manistee – MCRP Amendment – Jennifer Schwanky MSF/MSHDA/MEDC – MOU Amendment – Katharine Czarnecki Carhartt, Inc. – MBDP Grant Amendment – Trevor Friedeberg Suniva – MBDP Grant Amendment – Trevor Friedeberg Inteva – MBDP Amendment – Trevor Friedeberg FEV North America, Inc. – MBDP Grant Amendment – Marcia Gebarowski Fund Allocations: FY17 Allocation of Funds & Administrative Services MOU Renewal – Mark Morante Michigan Translational Research and Commercialization - Allocation of Funds – Denise Graves International Trade & STEP Grant – Allocation & Federal Grant Acceptance – Natalie Chmiko Procurement Technical Assistance Center – FY17 Grant Allocations – Andrea Robach B. Administrative Tool & Die Recovery Zone Policy – Josh Hundt/Christin Armstrong MBDP Program Guidelines Expansion – Josh Hundt Next Michigan Development Corporation Policy Recommendations – Andrea Robach Election of Officers – Mark Morante C. Business Investment a. Entrepreneurship MidMichigan Innovation Center – Business Incubator Grant Assignment – Fred Molnar University Early Stage “Proof of Concept” Fund – Request to Issue RFP – Fred Molnar Angel Capital Development Fund – Request to Issue RFP – Fred Molnar First Capital Fund – Request to Issue RFP – Fred Molnar FY17 Grant Amendments – Fred Molnar b. -

Solo Exhibition by SEEN February 23 – March 24, 2013

solo exhibition by SEEN February 23 – March 24, 2013 Fabien Castanier Gallery is proud to present [UN]SEEN, a solo exhibition by renowned graffiti artist SEEN. As the Godfather of Graffiti, originating from New York, SEEN is one of the most respected and established graffiti artists in the world. It has been 8 years since SEEN’s last solo exhibition on U.S. soil, and [UN]SEEN will mark the return of the legendary artist to America since moving to Europe in 2007. For this solo exhibition, the artist will exhibit never-before-shown abstract paintings created in Paris from 2007- 2012. SEEN, who has built his artistic career on perfecting the graffiti letter, presents exciting new paintings that are a distinct stylistic break from the graffiti work for which he has become known. When he moved to Paris in 2007, SEEN found the necessary time and inspiration to devote to experimentation. Those familiar with SEEN’s work will find this new series signifies his evolution as an artist. However, in true graffiti fashion, every piece is created with spray paint using various techniques that demonstrate the versatility of the spray can. The graffiti style of work – with the form of the letter – is what took off in the general public’s eye for me… I never showed the works that I was really getting into, which were more abstract. I kept that private… all these years I’ve kept it private. – SEEN (Interview with Fabien Castanier, January 2013) SEEN, aka Richard Mirando, was born in 1961 in The Bronx, New York. -

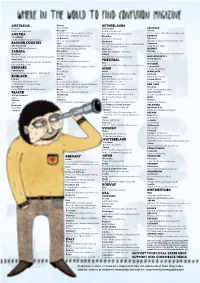

If You Have a Shop, Or Know of a Shop Not on This List, Please Email Their Shop Name, Contact, Address Or Whatever Information You Have To: [email protected]

AUSTRALIA Chelles NETHERLANDS Victoria Cosa Nostra Amsterdam COLORADO Riverslide skatepark Hossegor Rodolfos (rodolfos.nl) Aurora Carhartt Store (48 Avenue Paul Lahary) Denver Skate Shop (thedenvershop.com) AUSTRIA Carhartt Store (Hartenstraat 18) Volcom Store (202 Rue Paul Lahary) Deventer GEORGIA Tirol/Wörgl La Rochelle Norcross Pilotto Skate Shop (pilotto.com) Burnside (burnside.nl) Sirocco (siroccosk8.com) Eindhoven Woody’s Halfpipe (woodyshalfpipe.com) BASQUE COUNTRY Lyon 100% Skateboardshop (100procentskateshop.nl) Savannah San Sebastian Wall Street (wallstreetskateshop.com) Area 51 (area51skatepark.nl) Shut Up and Skate Carhartt Store (C/Garibai, 11) Carhartt Store (8 Rue Lanterne) Nijmegen ILLINOIS Canada Marseilles Waalhalla (waalhalla-centrum.nl) Chicago Montreal XOXO (xoxo-marseille.com) Tilburg Uprise Skate Shop (upriseskateshop.com) Underworld Skateshop (underworld-shop.com) Carhartt (51 Rue Saintes) Kingdom (kingdomskateshop.com) MASSACHUSETTS Vancouver Mâcon Northampton Smartplace (smartplaceskateshop.fr) PORTUGAL Boardroom Anti-Social Shop (antisocialshop.com/skate/) Faro Metz MISSOURI PD’s (skullskates.com) Jump Free Ride Store (Rua Dr. Justino Cúmano) Carhartt Store (C/Cial St Jacques – Cellule) Poplar Bluff DENMARK Nice SPAIN Extreme Boarding Copenhagen Four Wheels Aviles MINNESOTA Carhartt Store (Elmegade 13 – Birkegade 1) Nimes Bobskate (Fernández Balsera, 22, Avilés) Fairbault ENGLAND Tam Tam Barcelona Old School Skaters London Paris Carhartt Store (Carrer del Rec 71) Golden Valley Lovenskate (lovenskate.com) Nozbone -

Bread&&Butter by Zalando 2018 the Program

PRESS RELEASE BREAD&&BUTTER BY ZALANDO BREAD&&BUTTER BY ZALANDO 2018 THE PROGRAM Credit: Bread&&Butter by Zalando BREAD&&BUTTER BY ZALANDO - THE POP-UP OF STYLE AND CULTURE (B&&B) TAKES PLACE FROM 31 AUGUST – 2 SEPTEMBER AT ARENA BERLIN. THE EVENT’S PROGRAM FEATURES: +++ B&&B BRAND POP-UPS +++ 100+ EXCLUSIVE DROPS AND PRE-LAUNCHES BY 40+ INTERNATIONAL BRANDS, ADIDAS ORIGINALS, CARHARTT WIP, CONVERSE, DIESEL, LEVI’S®, MAC COSMETICS, NIKE, PUMA, REEBOK, THE NORTH FACE, TIMBERLAND, VANS, 032C, WEEKDAY, WRANGLER AND MORE. +++ B&&B SHOW POP-UPS +++ HUGO, MAC COSMETICS, ZALANDO AND MORE. +++ B&&B TALKS +++ 032C AND JÉRÔME BOATENG, G-STAR RAW AND JADEN SMITH, INSTAGRAM AND UGLYWORLDWIDE & GULLY GUY LEO, TIMBERLAND AND CHRISTOPHER RAEBURN, MERCEDES-BENZ AND MORE +++ B&&B MUSIC +++ 70+ ARTISTS: EVIAN CHRIST, HAMZA, KITTY CA$H, LUCIANO, PAIGEY CAKEY, PRINCESS NOKIA, SHECK WES, STEFFLON DON, UFO361, YUNG HURN AND MORE. HEAD TO BREADANDBUTTER.COM/SCHEDULE AND @BREADANDBUTTER FOR THE LATEST PROGRAM UPDATES. TICKETS ARE AVAILABLE VIA BREADANDBUTTER/TICKETS, AND CHECK OUT THE HOTTEST PRODUCTS ON BREADANDBUTTER.COM, THE SHOPPING HUB FOR SELECTED STREETWEAR AND EXCLUSIVE DROPS ON ZALANDO ON 31 AUGUST 2018. BERLIN, 2 AUGUST 2018 / From 31 August – 2 September Bread&&Butter by Zalando – The Pop-Up of Style and Culture (B&&B) celebrates its third edition at Arena Berlin. This year the event transforms into eight different B&&B districts for the ultimate urban experience. Here, visitors find 40+ brands, “see now, buy now” shopping options, next level customizations, workshops, Pop-Up shows, panel talks, a fire music line-up, appearances by today's cultural heroes and Berlin’s best street food. -

Facets of Graffiti Art and Street Art Documentation Online: a Domain and Content Analysis Ann Marie Graf University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations May 2018 Facets of Graffiti Art and Street Art Documentation Online: A Domain and Content Analysis Ann Marie Graf University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation Graf, Ann Marie, "Facets of Graffiti Art and Street Art Documentation Online: A Domain and Content Analysis" (2018). Theses and Dissertations. 1809. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/1809 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FACETS OF GRAFFITI ART AND STREET ART DOCUMENTATION ONLINE: A DOMAIN AND CONTENT ANALYSIS by Ann M. Graf A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Information Studies at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee May 2018 ABSTRACT FACETS OF GRAFFITI ART AND STREET ART DOCUMENTATION ONLINE: A DOMAIN AND CONTENT ANALYSIS by Ann M. Graf The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2018 Under the Supervision of Professor Richard P. Smiraglia In this dissertation research I have applied a mixed methods approach to analyze the documentation of street art and graffiti art in online collections. The data for this study comes from the organizational labels used on 241 websites that feature photographs of street art and graffiti art, as well as related textual information provided on these sites and interviews with thirteen of the curators of the sites. -

Motions 9:03 -Cv -80612 -KAM Securities Exchange V

CM/ECF - Live Database - flsd Page 1 of 6 Motions 9:03 -cv -80612 -KAM Securities Exchange v. Lauer, et al CASE CLOSED on 09/22/2009 U.S. District Court Southern District of Florida Notice of Electronic Filing The following transaction was entered by Bane, David on 8/10/2012 at 11:07 AM EDT and filed on 8/10/2012 Case Name: Securities Exchange v. Lauer, et al Case Number: 9:03 -cv -80612 -KAM Filer: Soneet R. Kapila WARNING: CASE CLOSED on 09/22/2009 Document Number: 2633 Docket Text: MOTION for Attorney Fees Thirteenth Interim Application For Allowance And Payment of Compensation And Reimbursement Of Expenses Incurred To Testifying Expert For Receiver For The Period September 1, 2011 Through April 30, 2012 by Soneet R. Kapila. Responses due by 8/27/2012 (Attachments: # (1) Exhibit A, # (2) Exhibit B, # (3) Exhibit C)(Bane, David) 9:03-cv-80612-KAM Notice has been electronically mailed to: Adam Jay Hodkin [email protected], [email protected] Adam M. Moskowitz [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Adrian J. Villaraos [email protected] Andrew Kamensky [email protected] Andrew David Zaron [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Andrew L. Jiranek [email protected] Camilo A Mejia [email protected], [email protected] Carmen Contreras-Martinez [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Christopher E. Martin [email protected], [email protected] Courtney Anne Caprio [email protected], [email protected] Craig -

Modern Mobility Textiles That Are Going Places

TRENDS IN APPAREL + FOOTWEAR DESIGN AND INNOVATION • JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2020 • A FORMULA4 MEDIA PUBLICATION MODERN MOBILITY TEXTILES THAT ARE GOING PLACES textileinsight.com • @textileinsight STROKE of Introducing LYCRA® FitSense™ technology for lightweight, targeted support. A breakthrough innovation that can be printed onto any part of any fabric. Discover more at LYCRA.com LYCRA FitSense EcoMade AO Textile Insight Print Ad x 2.indd 1 10/28/19 8:28 AM ® TEXTILE INSIGHT Editor/Associate Publisher Emily Walzer [email protected] Editorial Director Cara Griffin Art Director Francis Klaess Contributing Editors Suzanne Blecher Kurt Gray Jennifer Ernst Beaudry Kathlyn Swantko Publisher Jeff Nott [email protected] 516-305-4711 Production Brandon Christie 516 305-4710 [email protected] JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2020 Advertising Katie O’Donohue [email protected] 828-244-3043 Sam Selvaggio [email protected] 212-398-5021 Subscriptions: store.formula4media.com One year, $24.00 (U.S. Funds) in the United States. All other countries, $54.00 (U.S. Funds). Formula4Media ® Formula4 Media Publications Footwear Insight Footwear Insight Extra Outdoor Insight Team Insight Team Insight Extra Textile Insight Textile Insight Extra Trend Insight sportstyle PO Box 23-1318, Great Neck , NY 11023 Phone: 516-305-4709 Fax: 516-305-4712 In the Market ...................................................... 6 Footwear ................................................................ 34 www.formula4media.com A roundup of what’s hot for F/W 20; test method for Industry expert Simon Bartold discusses the materials and microfiber shedding debuts; new wools to watch; and more. science behind Nike’s much talked about VaporFly shoes. Textile Insight® is a registered trademark of Formula4 Media, LLC. ©2020 All Technology ...................................................... -

Textile Exchange Member Companies 20190410

Textile Exchange Member Companies Bottega Veneta Burberry 3M China Limited C.L.A.S.S. AATCC (American Association of Textile Chemicals and Colorists) C&A Buying AB Lindex C&A Foundation Acne Studios Canada Goose Adidas Sourcing Ltd. Canopy Planet Aditya Cott Fibre Carhartt, Inc. Aid by Trade Foundation (ABT) Casper Sleep Inc. Akasya Tarim Urun. A.S. Catholic Relief Services (CRS) Aksa Akrilik Kimya Sanayii A.S. | Aksa Acrylic Cathrine Hammel AS Chemical Company ChainPoint Alante Capital Change Agency Alexander McQueen (AMQ) Chang-Ho Fibre Corporation Alterra Pure Chargeurs Wool amelia°williams studio Charles & Keith Anandi Enterprises Chetana Society Anubha Industries Private Limited Chetana-Vikas Appachi Eco-Logic Project Circular Systems SPC Applied DNA Sciences (ADNAS) Clavis Partners, LLC ARC'TERYX Equipment Col&Bri Partners SL Armstrong Spinning Mills (P) Ltd. ColorZen Arvind Limited Columbia Sportswear Company Arvind Limited Farm Project Common Objective Asahi Kasei Corporation Concept III International Ascena Retail Group, Inc. Control Union Certifications ASOS.com COPROEXNIC ATB Costa Rican Investment Promotion Agency (CINDE) Aventura Clothing/Sportif USA CottonConnect Azureland Organic Co., Ltd. Cotton Council International Beechfield Brands Limited Country Road Group Bella Notte Linens Coyuchi, Inc. Bennett and Company Cradle to Cradle Products Innovation Institute Bergman/Rivera SAC CVS (Thailand) Co., Ltd. Bestseller A/S Darlington Fabrics Corporation Better Cotton Initiative (BCI) David Jones | Woolworths Holding Bhuvaneswari Tex Deer Creek Fabrics, Inc. Biocoton (India) Pvt Ltd/Sustainable Cotton Consultancy Delta Galil Industries Ltd. Boll & Branch LLC (Boll and Branch) Desigual Bolt Threads Dhana Inc. Bonobos Diadora S.p.A. Join us! Contact us for more Already a Member? Be part of the Updated April 10, 2019 information about Membership.