Chapter 2 CELESTIAL COORDINATE SYSTEMS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scienza E Cultura Universitalia

SCIENZA E CULTURA UNIVERSITALIA Costantino Sigismondi (ed.) ORBE NOVUS Astronomia e Studi Gerbertiani 1 Universitalia SIGISMONDI, Costantino (a cura di) Orbe Novus / Costantino Sigismondi Roma : Universitalia, 2010 158 p. ; 24 cm. – ( Scienza e Cultura ) ISBN … 1. Storia della Scienza. Storia della Chiesa. I. Sigismondi, Costantino. 509 – SCIENZE PURE, TRATTAMENTO STORICO 270 – STORIA DELLA CHIESA In copertina: Imago Gerberti dal medagliere capitolino e scritta ORBE NOVVS nell'epitaffio tombale di Silvestro II a S. Giovanni in Laterano (entrambe le foto sono di Daniela Velestino). Collana diretta da Rosalma Salina Borello e Luca Nicotra Prima edizione: maggio 2010 Universitalia INTRODUZIONE Introduzione Costantino Sigismondi L’edizione del convegno gerbertiano del 2009, in pieno anno internazionale dell’astronomia, si è tenuta nella Basilica di S. Maria degli Angeli e dei Martiri il 12 maggio, e a Seoul presso l’università Sejong l’11 giugno 2009. La scelta della Basilica è dovuta alla presenza della grande meridiana voluta dal papa Clemente XI Albani nel 1700, che ancora funziona e consente di fare misure di valore astrometrico. Il titolo di questi atti, ORBE NOVUS, è preso, come i precedenti, dall’epitaffio tombale di Silvestro II in Laterano, e vuole suggerire il legame con il “De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelestium” di Copernico, sebbene il contesto in cui queste parole sono tratte vuole inquadrare Gerberto nel suo ministero petrino come il nuovo pastore per tutto il mondo: UT FIERET PASTOR TOTO ORBE NOVVS. Elizabeth Cavicchi del Massachussets Institute of Technology, ha riflettuto sulle esperienze di ottica geometrica fatte da Gerberto con i tubi, nel contesto contemporaneo dello sviluppo dell’ottica nel mondo arabo con cui Gerberto era stato in contatto. -

Astrodynamics

Politecnico di Torino SEEDS SpacE Exploration and Development Systems Astrodynamics II Edition 2006 - 07 - Ver. 2.0.1 Author: Guido Colasurdo Dipartimento di Energetica Teacher: Giulio Avanzini Dipartimento di Ingegneria Aeronautica e Spaziale e-mail: [email protected] Contents 1 Two–Body Orbital Mechanics 1 1.1 BirthofAstrodynamics: Kepler’sLaws. ......... 1 1.2 Newton’sLawsofMotion ............................ ... 2 1.3 Newton’s Law of Universal Gravitation . ......... 3 1.4 The n–BodyProblem ................................. 4 1.5 Equation of Motion in the Two-Body Problem . ....... 5 1.6 PotentialEnergy ................................. ... 6 1.7 ConstantsoftheMotion . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .... 7 1.8 TrajectoryEquation .............................. .... 8 1.9 ConicSections ................................... 8 1.10 Relating Energy and Semi-major Axis . ........ 9 2 Two-Dimensional Analysis of Motion 11 2.1 ReferenceFrames................................. 11 2.2 Velocity and acceleration components . ......... 12 2.3 First-Order Scalar Equations of Motion . ......... 12 2.4 PerifocalReferenceFrame . ...... 13 2.5 FlightPathAngle ................................. 14 2.6 EllipticalOrbits................................ ..... 15 2.6.1 Geometry of an Elliptical Orbit . ..... 15 2.6.2 Period of an Elliptical Orbit . ..... 16 2.7 Time–of–Flight on the Elliptical Orbit . .......... 16 2.8 Extensiontohyperbolaandparabola. ........ 18 2.9 Circular and Escape Velocity, Hyperbolic Excess Speed . .............. 18 2.10 CosmicVelocities -

Constructing a Galactic Coordinate System Based on Near-Infrared and Radio Catalogs

A&A 536, A102 (2011) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201116947 & c ESO 2011 Astrophysics Constructing a Galactic coordinate system based on near-infrared and radio catalogs J.-C. Liu1,2,Z.Zhu1,2, and B. Hu3,4 1 Department of astronomy, Nanjing University, Nanjing 210093, PR China e-mail: [jcliu;zhuzi]@nju.edu.cn 2 key Laboratory of Modern Astronomy and Astrophysics (Nanjing University), Ministry of Education, Nanjing 210093, PR China 3 Purple Mountain Observatory, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Nanjing 210008, PR China 4 Graduate School of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, PR China e-mail: [email protected] Received 24 March 2011 / Accepted 13 October 2011 ABSTRACT Context. The definition of the Galactic coordinate system was announced by the IAU Sub-Commission 33b on behalf of the IAU in 1958. An unrigorous transformation was adopted by the Hipparcos group to transform the Galactic coordinate system from the FK4-based B1950.0 system to the FK5-based J2000.0 system or to the International Celestial Reference System (ICRS). For more than 50 years, the definition of the Galactic coordinate system has remained unchanged from this IAU1958 version. On the basis of deep and all-sky catalogs, the position of the Galactic plane can be revised and updated definitions of the Galactic coordinate systems can be proposed. Aims. We re-determine the position of the Galactic plane based on modern large catalogs, such as the Two-Micron All-Sky Survey (2MASS) and the SPECFIND v2.0. This paper also aims to propose a possible definition of the optimal Galactic coordinate system by adopting the ICRS position of the Sgr A* at the Galactic center. -

View and Print This Publication

@ SOUTHWEST FOREST SERVICE Forest and R U. S.DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE P.0. BOX 245, BERKELEY, CALIFORNIA 94701 Experime Computation of times of sunrise, sunset, and twilight in or near mountainous terrain Bill 6. Ryan Times of sunrise and sunset at specific mountain- ous locations often are important influences on for- estry operations. The change of heating of slopes and terrain at sunrise and sunset affects temperature, air density, and wind. The times of the changes in heat- ing are related to the times of reversal of slope and valley flows, surfacing of strong winds aloft, and the USDA Forest Service penetration inland of the sea breeze. The times when Research NO& PSW- 322 these meteorological reactions occur must be known 1977 if we are to predict fire behavior, smolce dispersion and trajectory, fallout patterns of airborne seeding and spraying, and prescribed burn results. ICnowledge of times of different levels of illumination, such as the beginning and ending of twilight, is necessary for scheduling operations or recreational endeavors that require natural light. The times of sunrise, sunset, and twilight at any particular location depend on such factors as latitude, longitude, time of year, elevation, and heights of the surrounding terrain. Use of the tables (such as The 1 Air Almanac1) to determine times is inconvenient Ryan, Bill C. because each table is applicable to only one location. 1977. Computation of times of sunrise, sunset, and hvilight in or near mountainous tersain. USDA Different tables are needed for each location and Forest Serv. Res. Note PSW-322, 4 p. Pacific corrections must then be made to the tables to ac- Southwest Forest and Range Exp. -

Basic Principles of Celestial Navigation James A

Basic principles of celestial navigation James A. Van Allena) Department of Physics and Astronomy, The University of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa 52242 ͑Received 16 January 2004; accepted 10 June 2004͒ Celestial navigation is a technique for determining one’s geographic position by the observation of identified stars, identified planets, the Sun, and the Moon. This subject has a multitude of refinements which, although valuable to a professional navigator, tend to obscure the basic principles. I describe these principles, give an analytical solution of the classical two-star-sight problem without any dependence on prior knowledge of position, and include several examples. Some approximations and simplifications are made in the interest of clarity. © 2004 American Association of Physics Teachers. ͓DOI: 10.1119/1.1778391͔ I. INTRODUCTION longitude ⌳ is between 0° and 360°, although often it is convenient to take the longitude westward of the prime me- Celestial navigation is a technique for determining one’s ridian to be between 0° and Ϫ180°. The longitude of P also geographic position by the observation of identified stars, can be specified by the plane angle in the equatorial plane identified planets, the Sun, and the Moon. Its basic principles whose vertex is at O with one radial line through the point at are a combination of rudimentary astronomical knowledge 1–3 which the meridian through P intersects the equatorial plane and spherical trigonometry. and the other radial line through the point G at which the Anyone who has been on a ship that is remote from any prime meridian intersects the equatorial plane ͑see Fig. -

Constellations with Prominent Stars That Can Be Found Near the Meridian at 10 Pm on January 15

ONSTELLATIONS C Altitude Ruler The rotation of the Earth on its axis causes the stars to rise and set each evening. In addition, the orbit of the Earth around the Sun places different regions of the sky in our Horizon night-time view. The PLANISPHERE is an extremely useful tool for finding stars and 10 constellation in the sky, depicting not only what is currently in the sky but it also allows the 20 prediction of the rising and setting times of various celestial objects. 30 THE LAYOUT OF THE PLANISPHERE 40 50 The outer circumference of the dark blue circular disk (which is called the star wheel) you’ll notice that the wheel is divided into the 12 months, and that each month is divided into 60 individual dates. The star wheel rotates about the brass fastener, which represents the 70 North Celestial Pole. The frame of the planisphere has times along the outer edge. 80 Holding the planisphere on the southern corner you'll see "midnight" at the top. Moving Zenith counterclockwise, notice how the hours progress, through 1 AM, 2 AM, and so on through "noon" at the bottom. The hours then proceed through the afternoon and evening (1 PM, 2 PM, etc.) back toward midnight. Once you have the wheel set properly for the correct time and day, the displayed part represents what you see if you stand with the star and planet locator held directly over your head with the brass fastener toward the north. (Notice that the compass directions are also written on the corners of the frame.) Of course, you don't have to actually stand that way to make use of the Star and Planet Locator--this is just a description to help you understand what is displayed. -

Equatorial and Cartesian Coordinates • Consider the Unit Sphere (“Unit”: I.E

Coordinate Transforms Equatorial and Cartesian Coordinates • Consider the unit sphere (“unit”: i.e. declination the distance from the center of the (δ) sphere to its surface is r = 1) • Then the equatorial coordinates Equator can be transformed into Cartesian coordinates: right ascension (α) – x = cos(α) cos(δ) – y = sin(α) cos(δ) z x – z = sin(δ) y • It can be much easier to use Cartesian coordinates for some manipulations of geometry in the sky Equatorial and Cartesian Coordinates • Consider the unit sphere (“unit”: i.e. the distance y x = Rcosα from the center of the y = Rsinα α R sphere to its surface is r = 1) x Right • Then the equatorial Ascension (α) coordinates can be transformed into Cartesian coordinates: declination (δ) – x = cos(α)cos(δ) z r = 1 – y = sin(α)cos(δ) δ R = rcosδ R – z = sin(δ) z = rsinδ Precession • Because the Earth is not a perfect sphere, it wobbles as it spins around its axis • This effect is known as precession • The equatorial coordinate system relies on the idea that the Earth rotates such that only Right Ascension, and not declination, is a time-dependent coordinate The effects of Precession • Currently, the star Polaris is the North Star (it lies roughly above the Earth’s North Pole at δ = 90oN) • But, over the course of about 26,000 years a variety of different points in the sky will truly be at δ = 90oN • The declination coordinate is time-dependent albeit on very long timescales • A precise astronomical coordinate system must account for this effect Equatorial coordinates and equinoxes • To account -

Earth-Centred Universe

Earth-centred Universe The fixed stars appear on the celestial sphere Earth rotates in one sidereal day The solar day is longer by about 4 minutes → scattered sunlight obscures the stars by day The constellations are historical → learn to recognise: Ursa Major, Ursa Minor, Cassiopeia, Pegasus, Auriga, Gemini, Orion, Taurus Sun’s Motion in the Sky The Sun moves West to East against the background of Stars Stars Stars stars Us Us Us Sun Sun Sun z z z Start 1 sidereal day later 1 solar day later Compared to the stars, the Sun takes on average 3 min 56.5 sec extra to go round once The Sun does not travel quite at a constant speed, making the actual length of a solar day vary throughout the year Pleiades Stars near the Sun Sun Above the atmosphere: stars seen near the Sun by the SOHO probe Shield Sun in Taurus Image: Hyades http://sohowww.nascom.nasa.g ov//data/realtime/javagif/gifs/20 070525_0042_c3.gif Constellations Figures courtesy: K & K From The Beauty of the Heavens by C. F. Blunt (1842) The Celestial Sphere The celestial sphere rotates anti-clockwise looking north → Its fixed points are the north celestial pole and the south celestial pole All the stars on the celestial equator are above the Earth’s equator How high in the sky is the pole star? It is as high as your latitude on the Earth Motion of the Sky (animated ) Courtesy: K & K Pole Star above the Horizon To north celestial pole Zenith The latitude of Northern horizon Aberdeen is the angle at 57º the centre of the Earth A Earth shown in the diagram as 57° 57º Equator Centre The pole star is the same angle above the northern horizon as your latitude. -

Chapter 7 Mapping The

BASICS OF RADIO ASTRONOMY Chapter 7 Mapping the Sky Objectives: When you have completed this chapter, you will be able to describe the terrestrial coordinate system; define and describe the relationship among the terms com- monly used in the “horizon” coordinate system, the “equatorial” coordinate system, the “ecliptic” coordinate system, and the “galactic” coordinate system; and describe the difference between an azimuth-elevation antenna and hour angle-declination antenna. In order to explore the universe, coordinates must be developed to consistently identify the locations of the observer and of the objects being observed in the sky. Because space is observed from Earth, Earth’s coordinate system must be established before space can be mapped. Earth rotates on its axis daily and revolves around the sun annually. These two facts have greatly complicated the history of observing space. However, once known, accu- rate maps of Earth could be made using stars as reference points, since most of the stars’ angular movements in relationship to each other are not readily noticeable during a human lifetime. Although the stars do move with respect to each other, this movement is observable for only a few close stars, using instruments and techniques of great precision and sensitivity. Earth’s Coordinate System A great circle is an imaginary circle on the surface of a sphere whose center is at the center of the sphere. The equator is a great circle. Great circles that pass through both the north and south poles are called meridians, or lines of longitude. For any point on the surface of Earth a meridian can be defined. -

Abd Al-Rahman Al-Sufi and His Book of the Fixed Stars: a Journey of Re-Discovery

ResearchOnline@JCU This file is part of the following reference: Hafez, Ihsan (2010) Abd al-Rahman al-Sufi and his book of the fixed stars: a journey of re-discovery. PhD thesis, James Cook University. Access to this file is available from: http://eprints.jcu.edu.au/28854/ The author has certified to JCU that they have made a reasonable effort to gain permission and acknowledge the owner of any third party copyright material included in this document. If you believe that this is not the case, please contact [email protected] and quote http://eprints.jcu.edu.au/28854/ 5.1 Extant Manuscripts of al-Ṣūfī’s Book Al-Ṣūfī’s ‘Book of the Fixed Stars’ dating from around A.D. 964, is one of the most important medieval Arabic treatises on astronomy. This major work contains an extensive star catalogue, which lists star co-ordinates and magnitude estimates, as well as detailed star charts. Other topics include descriptions of nebulae and Arabic folk astronomy. As I mentioned before, al-Ṣūfī’s work was first translated into Persian by al-Ṭūsī. It was also translated into Spanish in the 13th century during the reign of King Alfonso X. The introductory chapter of al-Ṣūfī’s work was first translated into French by J.J.A. Caussin de Parceval in 1831. However in 1874 it was entirely translated into French again by Hans Karl Frederik Schjellerup, whose work became the main reference used by most modern astronomical historians. In 1956 al-Ṣūfī’s Book of the fixed stars was printed in its original Arabic language in Hyderabad (India) by Dārat al-Ma‘aref al-‘Uthmānīa. -

And Are Lines on Sphere B That Contain Point Q

11-5 Spherical Geometry Name each of the following on sphere B. 3. a triangle SOLUTION: are examples of triangles on sphere B. 1. two lines containing point Q SOLUTION: and are lines on sphere B that contain point Q. ANSWER: 4. two segments on the same great circle SOLUTION: are segments on the same great circle. ANSWER: and 2. a segment containing point L SOLUTION: is a segment on sphere B that contains point L. ANSWER: SPORTS Determine whether figure X on each of the spheres shown is a line in spherical geometry. 5. Refer to the image on Page 829. SOLUTION: Notice that figure X does not go through the pole of ANSWER: the sphere. Therefore, figure X is not a great circle and so not a line in spherical geometry. ANSWER: no eSolutions Manual - Powered by Cognero Page 1 11-5 Spherical Geometry 6. Refer to the image on Page 829. 8. Perpendicular lines intersect at one point. SOLUTION: SOLUTION: Notice that the figure X passes through the center of Perpendicular great circles intersect at two points. the ball and is a great circle, so it is a line in spherical geometry. ANSWER: yes ANSWER: PERSEVERANC Determine whether the Perpendicular great circles intersect at two points. following postulate or property of plane Euclidean geometry has a corresponding Name two lines containing point M, a segment statement in spherical geometry. If so, write the containing point S, and a triangle in each of the corresponding statement. If not, explain your following spheres. reasoning. 7. The points on any line or line segment can be put into one-to-one correspondence with real numbers. -

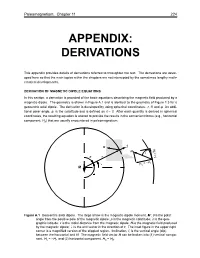

Appendix: Derivations

Paleomagnetism: Chapter 11 224 APPENDIX: DERIVATIONS This appendix provides details of derivations referred to throughout the text. The derivations are devel- oped here so that the main topics within the chapters are not interrupted by the sometimes lengthy math- ematical developments. DERIVATION OF MAGNETIC DIPOLE EQUATIONS In this section, a derivation is provided of the basic equations describing the magnetic field produced by a magnetic dipole. The geometry is shown in Figure A.1 and is identical to the geometry of Figure 1.3 for a geocentric axial dipole. The derivation is developed by using spherical coordinates: r, θ, and φ. An addi- tional polar angle, p, is the colatitude and is defined as π – θ. After each quantity is derived in spherical coordinates, the resulting equation is altered to provide the results in the convenient forms (e.g., horizontal component, Hh) that are usually encountered in paleomagnetism. H ^r H H h I = H p r = –Hr H v M Figure A.1 Geocentric axial dipole. The large arrow is the magnetic dipole moment, M ; θ is the polar angle from the positive pole of the magnetic dipole; p is the magnetic colatitude; λ is the geo- graphic latitude; r is the radial distance from the magnetic dipole; H is the magnetic field produced by the magnetic dipole; rˆ is the unit vector in the direction of r. The inset figure in the upper right corner is a magnified version of the stippled region. Inclination, I, is the vertical angle (dip) between the horizontal and H. The magnetic field vector H can be broken into (1) vertical compo- nent, Hv =–Hr, and (2) horizontal component, Hh = Hθ .