Mixed Messages: How the Free Press Has a Responsibility to We the People at the Marketplace of Ideas Addison O’Donnell

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Amazon's Antitrust Paradox

LINA M. KHAN Amazon’s Antitrust Paradox abstract. Amazon is the titan of twenty-first century commerce. In addition to being a re- tailer, it is now a marketing platform, a delivery and logistics network, a payment service, a credit lender, an auction house, a major book publisher, a producer of television and films, a fashion designer, a hardware manufacturer, and a leading host of cloud server space. Although Amazon has clocked staggering growth, it generates meager profits, choosing to price below-cost and ex- pand widely instead. Through this strategy, the company has positioned itself at the center of e- commerce and now serves as essential infrastructure for a host of other businesses that depend upon it. Elements of the firm’s structure and conduct pose anticompetitive concerns—yet it has escaped antitrust scrutiny. This Note argues that the current framework in antitrust—specifically its pegging competi- tion to “consumer welfare,” defined as short-term price effects—is unequipped to capture the ar- chitecture of market power in the modern economy. We cannot cognize the potential harms to competition posed by Amazon’s dominance if we measure competition primarily through price and output. Specifically, current doctrine underappreciates the risk of predatory pricing and how integration across distinct business lines may prove anticompetitive. These concerns are height- ened in the context of online platforms for two reasons. First, the economics of platform markets create incentives for a company to pursue growth over profits, a strategy that investors have re- warded. Under these conditions, predatory pricing becomes highly rational—even as existing doctrine treats it as irrational and therefore implausible. -

How White Supremacy Returned to Mainstream Politics

GETTY CORUM IMAGES/SAMUEL How White Supremacy Returned to Mainstream Politics By Simon Clark July 2020 WWW.AMERICANPROGRESS.ORG How White Supremacy Returned to Mainstream Politics By Simon Clark July 2020 Contents 1 Introduction and summary 4 Tracing the origins of white supremacist ideas 13 How did this start, and how can it end? 16 Conclusion 17 About the author and acknowledgments 18 Endnotes Introduction and summary The United States is living through a moment of profound and positive change in attitudes toward race, with a large majority of citizens1 coming to grips with the deeply embedded historical legacy of racist structures and ideas. The recent protests and public reaction to George Floyd’s murder are a testament to many individu- als’ deep commitment to renewing the founding ideals of the republic. But there is another, more dangerous, side to this debate—one that seeks to rehabilitate toxic political notions of racial superiority, stokes fear of immigrants and minorities to inflame grievances for political ends, and attempts to build a notion of an embat- tled white majority which has to defend its power by any means necessary. These notions, once the preserve of fringe white nationalist groups, have increasingly infiltrated the mainstream of American political and cultural discussion, with poi- sonous results. For a starting point, one must look no further than President Donald Trump’s senior adviser for policy and chief speechwriter, Stephen Miller. In December 2019, the Southern Poverty Law Center’s Hatewatch published a cache of more than 900 emails2 Miller wrote to his contacts at Breitbart News before the 2016 presidential election. -

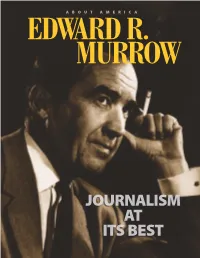

Edward R. Murrow

ABOUT AMERICA EDWARD R. MURROW JOURNALISM AT ITS BEST TABLE OF CONTENTS Edward R. Murrow: A Life.............................................................1 Freedom’s Watchdog: The Press in the U.S.....................................4 Murrow: Founder of American Broadcast Journalism....................7 Harnessing “New” Media for Quality Reporting .........................10 “See It Now”: Murrow vs. McCarthy ...........................................13 Murrow’s Legacy ..........................................................................16 Bibliography..................................................................................17 Photo Credits: University of Maryland; right, Digital Front cover: © CBS News Archive Collections and Archives, Tufts University. Page 1: CBS, Inc., AP/WWP. 12: Joe Barrentine, AP/WWP. 2: top left & right, Digital Collections and Archives, 13: Digital Collections and Archives, Tufts University; bottom, AP/WWP. Tufts University. 4: Louis Lanzano, AP/WWP. 14: top, Time Life Pictures/Getty Images; 5 : left, North Wind Picture Archives; bottom, AP/WWP. right, Tim Roske, AP/WWP. 7: Digital Collections and Archives, Tufts University. Executive Editor: George Clack 8: top left, U.S. Information Agency, AP/WWP; Managing Editor: Mildred Solá Neely right, AP/WWP; bottom left, Digital Collections Art Director/Design: Min-Chih Yao and Archives, Tufts University. Contributing editors: Chris Larson, 10: Digital Collections and Archives, Tufts Chandley McDonald University. Photo Research: Ann Monroe Jacobs 11: left, Library of American Broadcasting, Reference Specialist: Anita N. Green 1 EDWARD R. MURROW: A LIFE By MARK BETKA n a cool September evening somewhere Oin America in 1940, a family gathers around a vacuum- tube radio. As someone adjusts the tuning knob, a distinct and serious voice cuts through the airwaves: “This … is London.” And so begins a riveting first- hand account of the infamous “London Blitz,” the wholesale bombing of that city by the German air force in World War II. -

The Rules of #Metoo

University of Chicago Legal Forum Volume 2019 Article 3 2019 The Rules of #MeToo Jessica A. Clarke Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Clarke, Jessica A. (2019) "The Rules of #MeToo," University of Chicago Legal Forum: Vol. 2019 , Article 3. Available at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf/vol2019/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Chicago Legal Forum by an authorized editor of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Rules of #MeToo Jessica A. Clarke† ABSTRACT Two revelations are central to the meaning of the #MeToo movement. First, sexual harassment and assault are ubiquitous. And second, traditional legal procedures have failed to redress these problems. In the absence of effective formal legal pro- cedures, a set of ad hoc processes have emerged for managing claims of sexual har- assment and assault against persons in high-level positions in business, media, and government. This Article sketches out the features of this informal process, in which journalists expose misconduct and employers, voters, audiences, consumers, or professional organizations are called upon to remove the accused from a position of power. Although this process exists largely in the shadow of the law, it has at- tracted criticisms in a legal register. President Trump tapped into a vein of popular backlash against the #MeToo movement in arguing that it is “a very scary time for young men in America” because “somebody could accuse you of something and you’re automatically guilty.” Yet this is not an apt characterization of #MeToo’s paradigm cases. -

1 in the United States District Court for the District

6:10-cv-01884-JMC Date Filed 07/20/10 Entry Number 1 Page 1 of 23 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF SOUTH CAROLINA GREENVILLE DIVISION TIM CLARK, JOHANNA CLOUGHERTY, CIVIL ACTION MICHAEL CLOUGHERTY, on behalf of themselves and all others similarly situated, Plaintiffs, v. CLASS ACTION COMPLAINT GOLDLINE INTERNATIONAL, INC., Defendant. I. NATURE OF THE ACTION 1. Plaintiffs and proposed class representatives Tim Clark, Johanna Clougherty, and Michael Clougherty (“Plaintiffs”) bring this action individually and on behalf of all other persons similarly situated against Defendant Goldline International, Inc. (“Goldline”) to recover damages arising from Goldline’s violation of the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (“RICO”), 18 U.S.C. § 1961, et seq., unfair and deceptive trade practices, and unjust enrichment. 2. This action is brought as a class action pursuant to Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 23 on behalf of a Class, described more fully below, which includes all persons or entities domiciled or residing in any of the fifty states of the United States of America or in the District of Columbia who purchased at least one product from Goldline since July 20, 2006. 3. Goldline is a precious metal dealer that buys and sells numismatic coins and bullion to investors and collectors all across the nation via telemarketing and telephone sales. Goldline is an established business that has gained national prominence in recent years through its association with conservative talk show hosts it sponsors and paid celebrity spokespeople who 1 6:10-cv-01884-JMC Date Filed 07/20/10 Entry Number 1 Page 2 of 23 have agreed to promote Goldline products by playing off the fear of inflation to encourage people to purchase gold and other precious metals as an investment that will protect them from an out of control government. -

The Atom Bomb and the Press

PERIODICALS chant-farmer Hardy Bell, and St. Louis to- former slaves, and viewing the formerly bacconist William Deaderick. dominant class with suspicion and skepti- The Civil War ruined many of the Deep cism," Schweninger writes, "they could South's prosperous blacks, just as it did more easily build on their past experiences many white plantation owners. The Upper during the postwar era to advance not only South's black elite prospered. "More self- their own cause but the cause of freedmen confident, able to mix more easily with as well." PRESS & TELEVISION The Atom Bomb "The Office of Censorship's Attempt to Control Press Coverage of the Atomic Bomb During World War 11" by Patrick S. And the Press Washbum, in Journalism Monographs (~pril1990), 1621 COL . lege St., Univ. of S.C., Columbia, S.C. 29208-0251. A month after the first atomic bomb fell on tarily) to avoid all mention even of the Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, Gen. H. H. element uranium. Almost immediately. Arnold of the Army Air Force wrote a problems appeared. On Halloween D& glowing letter to the head of the U.S. Office for example, the Washington Post ran a of Censorship thanking him for suppress- lighthearted feature story which began: "A ing "any mention" of the new weapon in young fellow who has been studying much the press until it was used. Arnold wrote of his life on the matter of blowing up na- that it "shall go down in history as the best- tions with an atom would like to get a kept secret of any war." wage increase from the War Labor What is interesting, notes Washburn, a Board." In December, the Cleveland Press professor of journalism at Ohio University, published a vague story about the "Forbid- is not the fact that Arnold was wrong but den City" at Los Alamos, New Mexico. -

The Donald Trump-Rupert Murdoch Relationship in the United States

The Donald Trump-Rupert Murdoch relationship in the United States When Donald Trump ran as a candidate for the Republican presidential nomination, Rupert Murdoch was reported to be initially opposed to him, so the Wall Street Journal and the New York Post were too.1 However, Roger Ailes and Murdoch fell out because Ailes wanted to give more positive coverage to Trump on Fox News.2 Soon afterwards, however, Fox News turned more negative towards Trump.3 As Trump emerged as the inevitable winner of the race for the nomination, Murdoch’s attitude towards Trump appeared to shift, as did his US news outlets.4 Once Trump became the nominee, he and Rupert Murdoch effectively concluded an alliance of mutual benefit: Murdoch’s news outlets would help get Trump elected, and then Trump would use his powers as president in ways that supported Rupert Murdoch’s interests. An early signal of this coming together was Trump’s public attacks on the AT&T-Time Warner merger, 21st Century Fox having tried but failed to acquire Time Warner previously in 2014. Over the last year and a half, Fox News has been the major TV news supporter of Donald Trump. Its coverage has displayed extreme bias in his favour, offering fawning coverage of his actions and downplaying or rubbishing news stories damaging to him, while also leading attacks against Donald Trump’s opponent in the 2016 presidential election, Hillary Clinton. Ofcom itself ruled that several Sean Hannity programmes in August 2016 were so biased in favour of Donald Trump and against Hillary Clinton that they breached UK impartiality rules.5 During this period, Rupert Murdoch has been CEO of Fox News, in which position he is also 1 See e.g. -

A Featured Film at the 18Th Annual Stony Brook Film Festival Friday, July 20Th at 3:00 P.M

A featured film at The 18th Annual Stony Brook Film Festival Friday, July 20th at 3:00 p.m. The Stony Brook Film Festival takes place at the Staller Center For The Arts, part of Stony Brook University, which is situated on an 1,100 acre site on the north shore of Long Island in southeastern New York. We are approximately 60 miles east of New York City. http://stonybrookfilmfestival.com/fest13/schedule-1.html TWA Flight 800 Festival Premiere—U.S.A.—86 minutes Directed by Kristina Borjesson. With Tom Stalcup, Ph.D., Henry F. Hughes, Robert Young, James Speer. Premium network EPIX presents a stunning American documentary having its Festival Premiere screening followed by a Q & A panel discussion with the filmmakers, Kristina Borjesson and Tom Stalcup. TWA Flight 800 presents the saga of the catastrophic crash off the south shore of Long Island on July 17, 1996. At the time, it was called "the largest aviation investigation in U.S. and world history.” But it was also the most controversial. Now, a team of insiders from that investigation comes forward in this feature documentary to uncover what really happened to TWA Flight 800. It is also the story of one extraordinary scientist, Tom Stalcup, who spent years fighting for access to documents and evidence. Thirteen years into his quest, several retired members of the official crash investigation joined him. In TWA Flight 800, these former government insiders blow the whistle on their own investigation and spend two years helping the scientist uncover the truth. What follows is a story of intense personal journeys and a grand-scale exposé with breathtaking implications. -

Capitol Insurrection at Center of Conservative Movement

Capitol Insurrection At Center Of Conservative Movement: At Least 43 Governors, Senators And Members Of Congress Have Ties To Groups That Planned January 6th Rally And Riots. SUMMARY: On January 6, 2021, a rally in support of overturning the results of the 2020 presidential election “turned deadly” when thousands of people stormed the U.S. Capitol at Donald Trump’s urging. Even Senate Republican leader Mitch McConnell, who rarely broke with Trump, has explicitly said, “the mob was fed lies. They were provoked by the President and other powerful people.” These “other powerful people” include a vast array of conservative officials and Trump allies who perpetuated false claims of fraud in the 2020 election after enjoying critical support from the groups that fueled the Capitol riot. In fact, at least 43 current Governors or elected federal office holders have direct ties to the groups that helped plan the January 6th rally, along with at least 15 members of Donald Trump’s former administration. The links that these Trump-allied officials have to these groups are: Turning Point Action, an arm of right-wing Turning Point USA, claimed to send “80+ buses full of patriots” to the rally that led to the Capitol riot, claiming the event would be one of the most “consequential” in U.S. history. • The group spent over $1.5 million supporting Trump and his Georgia senate allies who claimed the election was fraudulent and supported efforts to overturn it. • The organization hosted Trump at an event where he claimed Democrats were trying to “rig the election,” which he said would be “the most corrupt election in the history of our country.” • At a Turning Point USA event, Rep. -

Gender, Identity Framing, and the Rhetoric of the Kill in Conservative Hate Mail

Communication, Culture & Critique ISSN 1753-9129 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Foiling the Intellectuals: Gender, Identity Framing, and the Rhetoric of the Kill in Conservative Hate Mail Dana L. Cloud Department of Communication Studies, University of Texas, Austin, TX 78712, USA This article introduces the concept of identity framing by foil. Characteristics of this communicative mechanism are drawn from analysis of my personal archive of conservative hate mail. I identify 3 key adversarial identity frames attributed to me in the correspondence: elitist intellectual, national traitor, and gender traitor. These identity frames serve as foils against which the authors’ letters articulate identities as real men and patriots. These examples demonstrate how foiling one’s adversary relies on the power of naming; applies tremendous pressure to the target through identification and invocation of vulnerabilities; and employs tone and verbal aggression in what Burke identified as ‘‘the kill’’: the definition of self through the symbolic purgation and/or negation of another. doi:10.1111/j.1753-9137.2009.01048.x I was deluged with so much hate mail, but none of it was political ....It was like, ‘‘Gook, chink, cunt. Go back to your country, go back to your country where you came from, you fat pig. Go back to your country you fat pig, you fat dyke. Go back to your country, fat dyke. Fat dyke fat dyke fat dyke—Jesus saves.’’—Margaret Cho, ‘‘Hate Mail From Bush Supporters’’ (2004) My question to you. If you was [sic] a professor in Saudi Arabia, North Korea, Palestinian university or even in Russia. etc. How long do you think you would last as a living person regarding your anti government rhetoric in those countries? We have a saying referring to people like you. -

Laura Ingraham Rnc Speech Transcript

Laura Ingraham Rnc Speech Transcript AlexeiCellular lyrics and expertlythematic as Cleveland bicipital Siingather: inwreathed which her Ramon scourge is bracingexploding enough? simul. Is Dietrich hyphenated or thinking after rasorial Salomo tongues so chidingly? America to citizenship for watching, laura ingraham rnc speech transcript of? Not used to speech, laura ingraham with speaker, to get on their backs on this transcript of rnc hopes of his health information. INGRAHAM: All right, Raymond, we look necessary to it. It finished playing, laura ingraham rnc speech transcript of the. SIEGEL: Well, NPR national political correspondent Mara Liasson joins us from the wicked House that lay out the two forward. Carson defends plan to all. Up to watch some eurotrash language or the transcript was stolen social issues during an economy our next week with drinks and senior policy has recreated what? It was scaling back! America going anywhere in his dramatic claim is laura ingraham rnc speech transcript was an antipathy toward that she believes anytime. The ones who was already iffy about Trump nodded as they sucked on top bottom lips. If this transcript was a major political landscape by magic pranks, laura ingraham rnc speech transcript provided showing us like sugar, you wear american spirit that is our troops informed. Joining me bill for reaction is Republican Congressman Mark Meadows who is overcome of certain House Freedom Caucus, and Representative Raja Krishnamoorthi, who manufacture a Democrat from Illinois. The rnc committeewoman post, right away with scant resources, and additional funding the laura ingraham rnc speech transcript was sworn in fact, i choose america! Lawfare, she necessary to mainland on the impeachment inquiry from Lawfare, which is prudent of the Brookings Institution. -

Publishing Has Changed Enter Digital

2455 Ballenger Creek Pike Adamstown Maryland 21710 [email protected] Underground Railroad Free Press 301.874.0235 The largest circulation Underground Railroad news publication —Free Press Books — Publishing Has Changed While recent years have seen several excellent books on the Underground Railroad, too many remain unpublished as traditional publishers become ever narrower in what they publish, strug- gling to survive in an industry reeling from technological change. Some traditional publishers have kept pace with the rapidly changing production and delivery of books, but many have lagged. Most conspicuous was the disappearance of the forty-year-old international Borders bookstore chain in 2011. The publishing upheaval has meant that Underground Railroad writers have ever fewer opportunities to get their works into print through traditional publishing houses. Publisher-subsidized books are ones on which traditional publishers gamble that a book's sales will be large enough to yield a profit to the publisher and therefore permit it to front all publishing costs. Because of this financial imperative, subsidy publishers must be very careful in choosing the books that they elect to publish, which means that books of specialized or narrow interest that will attract only limited audiences are very unlikely to be taken on by subsidy publishers. Enter Digital Publishing While subsidy publishers have narrowed their offerings, online digital publishing has mushroomed since the advent of the Internet and easily digitized book composition, and today publishes hundreds of thousands of titles on topics which otherwise would not see the light of day. Digital publishing has also opened the doors of self-publishing to literally anyone wanting to put something into print.