A Case Study of the Proposed Omkareshwar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Forest of Madhya Pradesh

Build Your Own Success Story! FOREST OF MADHYA PRADESH As per the report (ISFR) MP has the largest forest cover in the country followed by Arunachal Pradesh and Chhattisgarh. Forest Cover (Area-wise): Madhya Pradesh> Arunachal Pradesh> Chhattisgarh> Odisha> Maharashtra. Forest Cover (Percentage): Mizoram (85.4%)> Arunachal Pradesh (79.63%)> Meghalaya (76.33%) According to India State of Forest Report the recorded forest area of the state is 94,689 sq. km which is 30.72% of its geographical area. According to Indian state of forest Report (ISFR – 2019) the total forest cover in M.P. increased to 77,482.49 sq km which is 25.14% of the states geographical area. The forest area in MP is increased by 68.49 sq km. The first forest policy of Madhya Pradesh was made in 1952 and the second forest policy was made in 2005. Madhya Pradesh has a total of 925 forest villages of which 98 forest villages are deserted or located in national part and sanctuaries. MP is the first state to nationalise 100% of the forests. Among the districts, Balaghat has the densest forest cover, with 53.44 per cent of its area covered by forests. Ujjain (0.59 per cent) has the least forest cover among the districts In terms of forest canopy density classes: Very dense forest covers an area of 6676 sq km (2.17%) of the geograhical area. Moderately dense forest covers an area of 34, 341 sqkm (11.14% of geograhical area). Open forest covers an area of 36, 465 sq km (11.83% of geographical area) Madhya Pradesh has 0.06 sq km. -

Impact of Climate Change on Water Resources in Madhya Pradesh

Impact of Climate Change on Water Resources in Madhya Pradesh Impact of Climate Change on Water Resources in Madhya Pradesh Impacts of Climate Change on Water Resources in Madhya Pradesh - An Assessment Report This report is prepared under the financial support by Department for International Development (DFID) for the project Strengthening Performance Management in Government (SPMG) being implemented in Madhya Pradesh state of India. SPMG is an initiative of Department for International Development (DFID) to provide assistance to Government of Madhya Pradesh for strengthening planning and governance systems. One of the key focus areas of SPMG is to ensure environmental sustainability and climate compatible development in the state. As part of this initiative, Development Alternatives (DA) is recognized by Government of MP and DFID to provide technical support to Madhya Pradesh State Knowledge Management Centre on Climate Change (SKMCCC), EPCO. DA is assisting SKMCCC in facilitating integration of climate change concerns into departmental activities and plans, through strengthening technical capacities and generating strategic knowledge. Authors Dr. K.P Sudheer, Indian Institute of Technology, Madras Overall Guidance Mr. Anand Kumar, Ms. Harshita Bisht, Ms. Rowena Mathew, Development Alternatives (DA) Shri Ajatshatru Shrivastava, Executive Director, EPCO Mr. Lokendra Thakkar, Coordinator, State Knowledge Management Center on Climate Change, EPCO Acknowledgement We place on record our gratitude to the Department for International Development (DFID) for providing the financial and institutional support to this task and State Knowledge Management Centre on Climate Change (SKMCCC), EPCO, Government of Madhya Pradesh for their strategic guidance. Development Alternatives acknowledge the scientific expertise of Dr. K.P Sudheer from Indian Institute of Technology, Madras, for contributing in developing the impact assessment report. -

Seismic Hazard Estimation for Rani Avanti Bai Sagar Project at Bargi

International Journal of Civil Engineering and Technology (IJCIET) Volume 8, Issue 7, July 2017, pp. 78–87, Article ID: IJCIET_08_07_009 Available online at http:// http://iaeme.com/Home/issue/IJCIET?Volume=8&Issue=7 ISSN Print: 0976-6308 and ISSN Online: 0976-6316 © IAEME Publication Scopus Indexed SEISMIC HAZARD ESTIMATION FOR RANI AVANTI BAI SAGAR PROJECT AT BARGI Rakesh Kumar Grover Associate Professor, Department of Civil Engineering, Jabalpur Engineering College, Jabalpur (M.P.), India Dr. R. K. Tripathi Professor, Department of Civil Engineering, National Institute of Technology, Raipur (C.G.) India Dr. Rajeev Chandak Professor & Head, Deparment of Civil Engineering, Jabalpur Engineering College, Jabalpur (M.P.), India Dr. H. K. Mishra Principal, Indira Gandhi Engineering College, Sagar, (M.P.) India ABSTRACT Rani Avanti Bai Sagar Project at Bargi is a multipurpose project in the state of Madhya Pradesh (India). In this study seismic hazard has been estimated for Bargi Dam site. The probabilistic Seismic Hazard analysis has been used. Effects of all the faults, which can produce earthquake equal to or more than 3.5 Magnitude and those within a radius of 300 Km from the centre of the Masonry Dam has been considered. The past history of earthquakes indicated that a total 82 earthquakes, of magnitude 3.5 or more has been occurred in last 175 years. The maximum magnitude reported within the region of consideration is 6.5 in 1927 at Umaria. Probabilistic approach use these data for hazard Analysis. Results are presented in the form of peak ground acceleration and seismic hazard curves. Key words: Peak Ground Acceleration, Ground Motion, Bargi Dam, Seismic Hazard, Psha Cite this Article: Rakesh Kumar Grover, Dr. -

The Omkareshwar Dam in India : Closing Doors on Peoples' Future

The Omkareshwar Dam in India : Closing Doors on Peoples’ Future Abstract: The Omkareshwar Project is one of 30 large dams to be built in the Narmada Valley and which are being contested by one of India’s strongest grassroots movements. In Spring 2004 MIGA, the World Bank’s Investment Guarantee Agency, turned down an application for Omkareshwar because of “environmental and social concerns”. The project will displace 50,000 small farmers and flood up to 5800 hectars of one of Central India’s last intact natural forests. Construction of the dam was taken up in November 2003, in spite of the fact that no Environmental Impact Asessment and no resettlement plan has been prepared for the project. The project violates a number of national and international standards, including the so-called Equator Principles. Although it has been turned down by Deutsche Bank, several foreign banks and export credit agencies are still considering loan and insurance applications for Omkareshwar. Village Sukwa, Omkareshwar submergence area A number of European private banks and several Export Credit Agencies (ECAs) have been asked to provide support for the highly controversial Omkareshwar Dam Project in India. In November 2003, representatives of the Japan Center for Sustainable Environment and Society (JACSES) and the German environment and human rights NGO Urgewald undertook a fact-finding mission to the Omkareshwar area. The following report is based on data collected during our visit as well as discussions with the project sponsor, affected villagers and a review of all obtainable project documents. The Project and its Sponsor The Omkareshwar Project was conceived in 1965 as an irrigation and power dam to be built in the Central Indian State of Madhya Pradesh. -

Riverine Ecology and Fisheries •

Riverine ecology and fisheries •.. vis-a-vis hydrodynamic alterations: Impacts and remedial measures V. Pathak and R. K. Tyagi Bull. No. - 161 January - 2010 Central Inland Fisheries Research Institute (Indian Council of Agricultural Research) Barrackpore, Kolkata - 700120, West Bengal Riverine ecology and fisheries vis-a-vis hydrodynamic alterations: Impacts and remedial measures v. Pathak and R.K. Tyagi ISSN 0970-616X © 2009 Material contained in this Bulletin may not be reproduced, in any form, without the permission of the publisher Published by : Director, CIFRI,Barrackpore Edited By: Dr. P.K. Katiha Dr. R. K. Manna The Agricultural Economics Section and Project Monitoring and Documentation Cell, CIFRI,Barrackpore ) Printed at Eastern Printing Processor 93, Dakshindari Road, Kolkata - 48 90Vlf/(,/l/vYl/1!/ I!/DCPtCP'f'f (//Yl/d ?vSlIvI!/'I/VMy IContents subjects Page No. Foreword List of tables Hi List of figures Hi Introduction 1 Classification of rivers 1 Ecological status of rivers 4 Himalayan rivers Ganga 4 Ravi 5 Sutlej 5 Beas 5 Brahmaputra 7 Peninsular rivers Mahanadi 7 Godavari 8 Krishna 8 Cauvery 8 Narmada 9 Rate of energy transformation by producers 11 and fish production potential of rivers Fish fauna 13 Himalayan rivers 13 Peninsular rivers 18 90UIP(!/"I/U/1/f!/ f!/Cdyt<Y'F1f O//1/J ?us-/vf!/'I/Uf!/!v suifects Page No. Fishery 23 Himalayan rivers The Indus river system 23 Ganga 24 Brahmaputra 26 Peninsular rivers Mahanadi 27 Godavari 28 Krishna and Cauvery 29 Narmada 29 Tapti 30 Factors influencing fish production from rivers 30 Hydrological regimes 30 Environmental degradation 31 Fishing pressure 32 Conservation measures 34 90vlf/e/l/v/1/l!/ l!/C/{Yt{YfJ'1f (II/1/d fV!Y/vl!/'l/Vl!/!Y IForeword The vast network of Indian rivers and rivulets has been source for rich fish biodiversity, lucrative fishery and provide livelihood to countless riparian fishers. -

Aquatic Phyto-Biodiversity of Bargi Dam Catchment Area at Jabalpur, IJCRR Section: Healthcare Sci

International Journal of Current Research and Review Life Science DOI: 10.7324/IJCRR.2018.1049 Aquatic Phyto-Biodiversity of Bargi Dam Catchment Area at Jabalpur, IJCRR Section: Healthcare Sci. Journal Madhya Pradesh: An Appraisal Impact Factor 4.016 ICV: 71.54 Dharmendra Kumar Parte1, S. D. Upadhyaya2, R. P. Mishra3, C. P. Rahangdale4, Sajad Ahmad Mir5, Anu Mishra6 1Research Scholar at RDVV Jabalpur; 2Prof. and Head Department of Forestry JNKVV Jabalpur, MP, India; 3Prof. at Department of Biological Sciences RDVV Jabalpur; 4SRF, ISRO Project Department of Plant Physiology JNKVV Jabalpur, MP, India; 5Research Scholar at Department of Biological Sciences RDVV Jabalpur; 6JRF at JNKVV Jabalpur, MP, India. ABSTRACT Aim: The study was conducted on Bargi Dam catchment area at Jabalpur district of Madhya Pradesh with the objective of De- termining “The Aquatic species Floristic Composition Diversity and the Vegetation Structure of the Aquatic Plants Communities in the Bargi Dam Catchment Area”. Methodology: Random sampling method was used to collect the vegetation data according to 36 plots of per quadrates 10m x10m size. Results: A total of 119 species belonging to 79 genera and 39 families were recorded during the survey in which emergent 61%, marshy land 21%, free floating 9%, rooted floating 1%, submerged 8% aquatic plants were identified from the Bargi Dam catchment area. Key Words: Wetland, Catchment, Floristic composition, Aquatic plants INTRODUCTION are key components for the well-functioning of wetland eco- system for biological productivity, supporting diverse com- Aquatic ecosystems play an important role in human life. munity of ecosystem by providing lots of goods and services. -

Narmada Control Authority Presentation

National Level Three Day Programme on Best Practices in Water Resources Sector 26-28 October,2017 at APHRDI,Bapatla Narmada Control Authority - Transforming Conflict into Cooperation amongst riparian States by Dr. MUKESH KUMAR SINHA EXECUTIVE MEMBER, NARMADA CONTROL AUTHORITY MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES, RIVER DEVELOPMENT & GANGA REJUVENATION Government of India 1 Narmada River Fifth Largest River Of India Largest West Flowing River River Length - 1312 km (from Amarkantak to Arabian Sea) Catchment Area - 98,000 km2 Mean Annual Rainfall - 1,180 mm Average Annual Run-Off - 41,000 MCM (33.21 MAF) 2 NARMADA RIVER BASIN - 30 Major Projects, 135 Medium Projects and over 3000 Minor Schemes Narmada Main Canal Indira Sagar Dam Bargi Dam Sardar Sarovar Dam Omkareshwar Dam Maheshwar Dam 3 Narmada Water Disputes Tribunal Constituted by Govt. of India under Section 4 of the Inter-State Water Disputes Act, 1956 through notification no. SO 4054 dated 6th October, 1969, to adjudicate the water dispute between the States of Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra and Rajasthan over the use, distribution and control of the waters of the inter-state river Narmada. On 16 August 1978, the Tribunal declared its Award under Section 5(2) read with Section 5(4) of the Inter-State Water Disputes Act, 1956. Thereafter, references were filed by the Union of India and the States of Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra and Rajasthan respectively under Section 5(3) of the Inter-State Water Disputes Act, 1956. These references were heard by the Tribunal and on 7 December 1979 gave its final order. The same was published in the extraordinary Gazette by the Government of India on 12 December 1979. -

Full Case Study (Pdf)

ABSTRACT Case Title: India: A tale of rehabilitation of people displaced due to dam construction (#250) Subtitle: Describes the process of rehabilitating people displaced due to construction of the Bargi Dam, from initial agitations to eventual resolution of conflict. Description The construction of the Bargi Dam (1971-1990) on the river Narmada affected 27432 ha of land and displaced 5,475 families. Initially provision was made only for payment of compensation for land and property. The lack of planning for human problems led eventually to an agitation lasting over several years. On receiving complaints from the affected people the Commissioner of Social Welfare intervened in 1986 and convinced the state to prepare a rehabilitation plan of Rs.100 million (US$ 2 million). Delay and mismanagement, including rehabilitation work in places not affected by the dam, led to the displaced people coming together to form a Union. Demonstrations began in 1992, demanding fishing rights and protesting against the complete filling up of the dam. In 1994, the Chief Minister met the displaced people, accepted responsibility for rehabilitation, and agreed to some of the demands. To speed up the works, a divisional level planning committee was set up which drew up a rehabilitation plan, but its implementation was held up due to delays in obtaining funding. In 1996, violent demonstrations resumed demanding reduction of the reservoir water level. The Chief Secretary visited the affected area, met the Union, and agreed to demands. The cycle of non-implementation, agitation and subsequent agreement to some demands was repeated in 1997. Since then rehabilitation work has been carried out in cooperation between the Union and the government. -

The Sardar Sarovar Dam Project: Selected Documents Level

Chapter 1 The Sardar Sarovar Dam Project: An Overview Philippe Cullet The Sardar Sarovar Project (SSP) is part of a gigantic scheme seeking to build more than 3,000 dams, including 30 big dams, on the river Narmada, a 1,312 km river flowing westwards from Amarkantak in Madhya Pradesh, touching Maharashtra and ending its course in Gujarat. The SSP is a multi-purpose dam and canal system whose primary rationale is to provide irrigation and drinking water. Power generation is another expected benefit. It is the second biggest of the proposed dams on the Narmada, and its canal network is projected to be the largest in the world. The dam is situated in the state of Gujarat, which will derive most of the benefits of the project, but the submergence – 37,533 hectares in total – is primarily affecting the state of MP (55 per cent) and to a much lesser extent the state of Maharashtra. The SSP has been one of the most debated development projects of the past several decades in India and at the international level. It is only one of many similar big projects in the Narmada valley and in India generally but it has acquired a symbolic status in development debates. This is due in part to the complexity of such multi-purpose projects and the multiple positive and negative impacts associated with big dams. This is also due to the specificities of this project, which was first proposed nearly 60 years ago. Firstly, the fact that this project involves four states – Gujarat, MP, Maharashtra and Rajasthan – with the state of Gujarat receiving most of the benefits of the project has repeatedly led to disagreements among the concerned states. -

General-STATIC-BOLT.Pdf

oliveboard Static General Static Facts CLICK HERE TO PREPARE FOR IBPS, SSC, SBI, RAILWAYS & RBI EXAMS IN ONE PLACE Bolt is a series of GK Summary ebooks by Oliveboard for quick revision oliveboard.in www.oliveboard.in Table of Contents International Organizations and their Headquarters ................................................................................................. 3 Organizations and Reports .......................................................................................................................................... 5 Heritage Sites in India .................................................................................................................................................. 7 Important Dams in India ............................................................................................................................................... 8 Rivers and Cities On their Banks In India .................................................................................................................. 10 Important Awards and their Fields ............................................................................................................................ 12 List of Important Ports in India .................................................................................................................................. 12 List of Important Airports in India ............................................................................................................................. 13 List of Important -

Socio- Political and Administrative History of Ancient India (Early Time to 8Th-12Th Century C.E)

DDCE/History (M.A)/SLM/Paper-XII Socio- Political and Administrative History of Ancient India (Early time to 8th-12th Century C.E) By Dr. Binod Bihari Satpathy 0 CONTENT SOCIO- POLITICAL AND ADMINISTRATIVE HISTORY OF ANCIENT INDIA (EARLY TIME TO 8th-12th CENTURIES C.E) Unit.No. Chapter Name Page No Unit-I. Political Condition. 1. The emergence of Rajput: Pratiharas, Art and Architecture. 02-14 2. The Rashtrakutas of Manyakheta: Their role in history, 15-27 Contribution to art and culture. 3. The Pala of Bengal- Polity, Economy and Social conditions. 28-47 Unit-II Other political dynasties of early medieval India. 1. The Somavamsis of Odisha. 48-64 2. Cholas Empire: Local Self Government, Art and Architecture. 65-82 3. Features of Indian Village System, Society, Economy, Art and 83-99 learning in South India. Unit-III. Indian Society in early Medieval Age. 1. Social stratification: Proliferation of castes, Status of women, 100-112 Matrilineal System, Aryanisation of hinterland region. 2. Religion-Bhakti Movements, Saivism, Vaishnavism, Tantricism, 113-128 Islam. 3. Development of Art and Architecture: Evolution of Temple Architecture- Major regional Schools, Sculpture, Bronzes and 129-145 Paintings. Unit-IV. Indian Economy in early medieval age. 1. General review of the economic life: Agrarian and Urban 146-161 Economy. 2. Indian Feudalism: Characteristic, Nature and features. 162-180 Significance. 3. Trade and commerce- Maritime Activities, Spread of Indian 181-199 Culture abroad, Cultural Interaction. 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT It is pleasure to be able to complete this compilation work. containing various aspects of Ancient Indian History. This material is prepared with an objective to familiarize the students of M.A History, DDCE Utkal University on the various aspcets of India’s ancient past. -

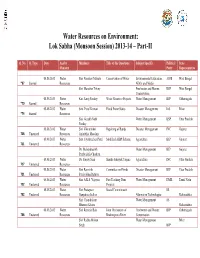

Water Resources on Environment: Lok Sabha (Monsoon Session) 2013-14 – Part-II

Water Resources on Environment: Lok Sabha (Monsoon Session) 2013-14 – Part-II Q. No. Q. Type Date Ans by Members Title of the Questions Subject Specific Political State Ministry Party Representative 08.08.2013 Water Shri Narahari Mahato Conservation of Water Environmental Education, AIFB West Bengal *67 Starred Resources NGOs and Media Shri Manohar Tirkey Freshwater and Marine RSP West Bengal Conservation 08.08.2013 Water Km. Saroj Pandey Water Resource Projects Water Management BJP Chhattisgarh *70 Starred Resources 08.08.2013 Water Smt. Putul Kumari Flood Prone States Disaster Management Ind. Bihar *74 Starred Resources Shri Gorakh Nath Water Management BSP Uttar Pradesh Pandey 08.08.2013 Water Shri Vikrambhai Repairing of Bunds Disaster Management INC Gujarat 708 Unstarred Resources Arjanbhai Maadam 08.08.2013 Water Smt. Jayshreeben Patel Modified AIBP Scheme Agriculture BJP Gujarat 711 Unstarred Resources Dr. Mahendrasinh Water Management BJP Gujarat Pruthvisinh Chauhan 08.08.2013 Water Dr. Sanjay Sinh Sharda Sahayak Yojana Agriculture INC Uttar Pradesh 717 Unstarred Resources 08.08.2013 Water Shri Ramsinh Committee on Floods Disaster Management BJP Uttar Pradesh 721 Unstarred Resources Patalyabhai Rathwa 08.08.2013 Water Shri A.K.S. Vijayan Fast Tracking Dam Water Management DMK Tamil Nadu 722 Unstarred Resources Projects 08.08.2013 Water Shri Prataprao Social Commitment SS 752 Unstarred Resources Ganpatrao Jadhav Alternative Technologies Maharashtra Shri Chandrakant Water Management SS Bhaurao Khaire Maharashtra 08.08.2013 Water