4.3. Edinburgh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Edinburgh PDF Map Citywide Website Small

EDINBURGH North One grid square on the map represents approximately Citywide 30 minutes walk. WATER R EAK B W R U R TE H O A A B W R R AK B A E O R B U H R N R U V O O B I T R E N A W A H R R N G Y E A T E S W W E D V A O DRI R HESP B BOUR S R E W A R U H U H S R N C E A ER R P R T O B S S S E SW E O W H U A R Y R E T P L A HE B A C D E To find out more To travel around Other maps SP ERU W S C Royal Forth K T R OS A E S D WA E OA E Y PORT OF LEITH R Yacht Club R E E R R B C O T H A S S ST N L W E T P R U E N while you are in the Edinburgh and go are available to N T E E T GRANTON S S V V A I E A E R H HARBOUR H C D W R E W A N E V ST H N A I city centre: further afield: download: R S BO AND U P R CH RO IP AD O E ROYAL YACHT BRITANNIA L R IMPERIAL DOCK R Gypsy Brae O A Recreation Ground NEWHAVEN D E HARBOUR D Debenhams A NUE TON ROAD N AVE AN A ONT R M PL RFR G PIE EL SI L ES ATE T R PLA V ER WES W S LOWE CE R KNO E R G O RAN S G T E 12 D W R ON D A A NEWHAVEN MAIN RO N AD STREET R Ocean R E TO RIN K RO IV O G N T IT BAN E SH Granton RA R Y TAR T NT O C R S Victoria Terminal S O A ES O E N D E Silverknowes Crescent VIE OCEAN DRIV C W W Primary School E Starbank A N Golf Course D Park B LIN R OSWALL R D IV DRI 12 OAD Park SA E RINE VE CENT 13 L Y A ES P A M N CR RIMR R O O V O RAN T SE BA NEWHAVEN A G E NK RO D AD R C ALE O Forthquarter Park R RNV PORT OF LEITH & A O CK WTH 14 ALBERT DOCK I HA THE SHORE G B P GRANTON H D A A I O LT A Come aboard a floating royal N R W N L O T O O B K D L A W T A O C O R residence or visit the dockside bars Scottish N R N T A N R E E R R Y R S SC I E A EST E D L G W N O R D T D O N N C D D and bistros; steeped in maritime S A L A T E A E I S I A A Government DRI Edinburgh College I A A M K W R L D T P E R R O D PA L O Y D history and strong local identity. -

Transport and Environment Committee

Item 7.15 Transport and Environment Committee 10.00am, Thursday, 20 June 2019 Annual Update on Council Transport Arms Length Companies Executive/routine Executive Wards All Council Commitments N/A 1. Recommendations 1.1 Transport and Environment Committee is asked to: 1.1.1 Note the progress of the three Council arms length companies (Transport for Edinburgh (TfE), Edinburgh Trams Limited (ETL) and Lothian Buses (LB) over the past 12 months; and 1.1.2 Refer this report to Governance Risk and Best Value Committee for noting, as part of the Council’s governance arrangements. Paul Lawrence Executive Director of Place Contact: Paul Lawrence, Executive Director of Place E-mail: [email protected] | Tel: 0131 529 7325 Report Annual Update on the Council Transport Arms Length Companies 2. Executive Summary 2.1 This report sets out the progress made by TfE, ETL and LB over the last 12 months and is reported in line with the Council’s governance arrangements, which require an annual update on performance of arms length organisations. This is the first report on the Transport companies. 3. Background 3.1 On 22 August 2013, in establishing the arrangements for the operation of the new Edinburgh Tram, Council approved the establishment of TfE. This company now holds the Council’s shareholding in both LB and ETL. This shareholding is as follows: 100% of ETL and 91.01% of shares in LB (with the balance owned by East Lothian, West Lothian and Midlothian Councils). 3.2 The most recent update on the three companies was considered by Transport and Environment Committee on 17 January 2016. -

Mcgill University

McGill University Department of Geography MASTER'S THEsrs An Analysis ofthe Feasibilîty of Developing a Network of Residential Outdoor Schools Within the Canadian Biosphere Reserve Association. A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research In partial·fulfillment of the degree of Masters ofArts Subrnittedby: Jaime Alexandra Webbe Geography Student ID No.: 9534115 © Jaime Alexandra Webbe, 2001 Nationallibrary Bibliothèque nationale of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 WellingtQnStreet 395. rue Wellington OttawaON K1A ON4 Ottawa ON K1 A 004 Canada Canada The author has granted a non L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive pennettant àla NationalLibrary ofCanada to Bibliothèque nationale· du Canada de reproduce, lom, distribute or sen reproduire, prêter,•distribuer. ou copies ofthis thesisin microform, vendre des. copies de cette thèSe sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/film,. de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership ofthe L'auteur conseIVe la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neitherthe droit d'auteur qui prot~gecette thèse. thesis nor substantialextracts frOID it Nila thèse ni des extrâits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou· autreIUent reproduits sans son pemnssIOn. autorisation. 0-612-79051-7 Canada Page 2 Table of Contents 1 Introduction 7 1.1 Environmental Education -

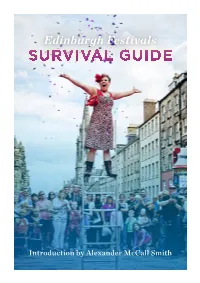

Survival Guide

Edinburgh Festivals SURVIVAL GUIDE Introduction by Alexander McCall Smith INTRODUCTION The original Edinburgh Festival was a wonderful gesture. In 1947, Britain was a dreary and difficult place to live, with the hardships and shortages of the Second World War still very much in evidence. The idea was to promote joyful celebration of the arts that would bring colour and excitement back into daily life. It worked, and the Edinburgh International Festival visitor might find a suitable festival even at the less rapidly became one of the leading arts festivals of obvious times of the year. The Scottish International the world. Edinburgh in the late summer came to be Storytelling Festival, for example, takes place in the synonymous with artistic celebration and sheer joy, shortening days of late October and early November, not just for the people of Edinburgh and Scotland, and, at what might be the coldest, darkest time of the but for everybody. year, there is the remarkable Edinburgh’s Hogmany, But then something rather interesting happened. one of the world’s biggest parties. The Hogmany The city had shown itself to be the ideal place for a celebration and the events that go with it allow many festival, and it was not long before the excitement thousands of people to see the light at the end of and enthusiasm of the International Festival began to winter’s tunnel. spill over into other artistic celebrations. There was How has this happened? At the heart of this the Fringe, the unofficial but highly popular younger is the fact that Edinburgh is, quite simply, one of sibling of the official Festival, but that was just the the most beautiful cities in the world. -

Local Transport Strategy Draft

Contents Executive Summary 1. Introduction 2. Vision and performance 3. Putting our customers first 4. Sustaining a thriving city 5. Protecting our environment 6. Road safety 7. Managing and maintaining our infrastructure 8. Travel planning, travel choices and marketing 9. Active travel 10. Public transport 11. Car and motorcycle travel 12. Car parking 13. Freight 14. Edinburgh’s connectivity 15. Making it happen Appendix 1 – Our indicators Appendix 2 – Plan and programme Appendix 3 – Policy documents Appendix 4 - References 1 Foreword "A developed country is not a place where the poor have cars. It's where the rich use public transport." Enrique Peñalosa, one time mayor of Bogota. The last ten years have seen achievements that Edinburgh can be proud of. We are the only city in Scotland that saw seen walking, cycling and public transport all strengthen their role between the 2001 and 2011 censuses. Edinburgh now boasts the highest share of travel to work in Scotland by each of foot, cycle and bus and the highest share in the UK for bus. We have also bucked Scottish and UK trends in car ownership; despite increasing affluence, a lower percentage of Edinburgh households owned a car in 2011 than 2001. The next five years promise to be an exciting time. We have delivered the first phase of the new Tram line, and can finally enjoy all its benefits. Transport for Edinburgh will be working to deliver increased integration and co-ordination of the wider public transport network. Edinburgh is joining the growing list of progressive UK cities putting people first through applying 20mph speed limits. -

Forest Understory Monitoring Protocols for Stanley Park Ecology Society Vancouver, BC

ER 390 Final Project Report Forest Understory Monitoring Protocols For Stanley Park Ecology Society Vancouver, BC Prepared for Restoration of Natural Systems Program University of Victoria Megan Spencer Student # V00754774 November 2017 Spencer | 1 Table of Contents List of Tables …………………………………………………………………………………….... 2 List of Figures ……………………………………………………………………………………... 2 List of Appendices ………………………………………………………………………………… 2 Abstract ……………………………………………………………………………………………. 3 Acknowledgements ………………………………………………………………………………... 3 1. Introduction ……………………………………………………………………...……. 4 1.1 Goal …………………………………………………………………………... 4 1.2 Objectives ……………………………………………………………………. 4 1.3 Why implement monitoring protocols? …..………………………………... 4 1.4 Citizen science and ecological monitoring ……………………….………… 5 2. Study Area …………………………………………………………………….………. 6 2.1 Overview ………………………………………………………….………….. 6 2.2 First Nations and settler history ………………………………….………… 7 2.3 Modern land-use status ………………………………………….………….. 7 3. Methods …………………………………………………………………….…………. 8 3.1 Site selection and field visits …………….…………………….…………… 8 3.2 Long-term monitoring plots ………………….…………………….…..….. 10 3.3 Pilot surveys ……………………………………………………….….……... 10 4. Results ……………………………………………….………………...……....….…… 11 4.1 Site selection and field visits ………………………….…………......……… 11 4.2 Long-term monitoring plots ………………………………..………....….… 13 4.3 Pilot surveys …………………………………………………………..…..….. 14 5. Discussion ………………………………………………………………………..…..… 15 5.1 Overview and context of results …………………..……………..…..…..… 15 5.2 Statistical -

Muirhouse • Pilton • Ferry Road • Leith • Bridges • Prestonfield • Greendykes

service 14 at a glance... frequency During the day During the day During the day During the Mon-Fri Saturday Sunday evening every every every every 12 15 20 30 mins mins mins mins City Centre bus stops Omni Centre See previous page for City Centre bus stops Whilst we’ve taken every effort in the preparation of this guide, Lothian Buses Ltd cannot accept any liability arising from inaccuracies, amendments or changes. The routes and times shown are for guidance – we would advise customers to check details by calling 0131 555 6363 before travelling. On occasion due to circumstances beyond our control and during special events, our services can be delayed by traffic congestion and diversion. 14 Muirhouse • Pilton • Ferry Road • Leith • Bridges • Prestonfield • Greendykes Muirhouse, Pennywell Place — — — 0552 — — 0617 — — 0637 0649 0700 0713 0724 0735 0747 0759 0811 0823 Pilton, Granton Primary — — — 0558 — — 0623 — — 0643 0655 0706 0719 0731 0742 0754 0806 0818 0830 Goldenacre — — — 0603 — — 0628 — — 0649 0701 0712 0726 0738 0749 0803 0815 0827 0839 Leith Walk (foot) — — — 0610 — — 0635 — — 0658 0710 0721 0738 0750 0802 0816 0828 0840 0852 Elm Row 0518 0538 0558 0615 0626 0634 0640 0654 0701 0705 0717 0728 0745 0757 0809 0823 0835 0847 0859 North Bridge 0522 0542 0602 0619 0630 0638 0644 0658 0705 0709 0721 0733 0751 0803 0815 0829 0841 0853 0905 Friday to Monday Prestonfield Avenue, East End 0531 0551 0611 0628 0639 0648 0654 0708 0715 0719 0734 0746 0806 0818 0830 0844 0856 0908 0920 Greendykes Terminus 0538 0558 0618 0635 0647 0656 0702 -

300 Airport • Gyle • Sighthill • Chesser • Fountainbridge • Surgeons’ Hall • Newington • Cameron Toll

Services X12 & Skylink 400 also serve RBS Gogarburn - see separate timetable leaflets for details. Whilst we’ve taken every effort in the preparation of this guide, Lothian Buses Ltd cannot accept any liability arising from inaccuracies, amendments or changes. The routes and times shown are for guidance – we would advise customers to check details by calling 0131 555 6363 before travelling. On occasion due to circumstances beyond our control and during special events, our services can be delayed by traffic congestion and diversion. 300 Airport • Gyle • Sighthill • Chesser • Fountainbridge • Surgeons’ Hall • Newington • Cameron Toll Edinburgh Airport — — — — 0550 — 0620 — 0650 — 0725 0750 0810 — 0837 0857 0920 0940 1000 Ingliston Park & Ride — — — — 0554 — 0624 — 0655 — 0730 0755 0815 0835 0842 0902 0925 0945 1005 RBS Gogarburn — — — — 0558 — 0628 — 0659 — 0735 0800 0820 0840 0847 0907 0929 0949 1009 Gyle Centre — — — — 0602 — 0632 — 0704 — 0740 0806 0826 0846 0853 0913 0934 0954 1014 Edinburgh Park, Redheughs Ave — — — — 0604 — 0634 — 0707 — 0744 0810 0830 0850 0857 0917 0937 0957 1017 Friday to Monday Sighthill, Napier Uni G G G G 0609 G 0639 0655 0713 0731 0751 0817 0837 0857 0904 0924 0944 1004 1024 Saughton Mains 0419 0449 0519 0549 0612 0627 0642 0659 0717 0736 0756 0822 0842 L 0909 0929 0949 1009 1029 Slateford Station 0423 0453 0523 0553 0617 0632 0647 0704 0722 0743 0803 0830 0850 — 0916 0936 0956 1016 1036 Fountainbridge, Semple St 0431 0501 0531 0601 0625 0640 0656 0716 0735 0801 0821 0848 0908 — 0929 0949 1009 1029 1049 Surgeons’ -

PTA Models of Organisation for Regional Transport Governance

5. Appx 1 Southeast Scotland Transport Partnership PTA models of organisation for regional transport governance Report Project No: 67751 November 16 Transport Research Institute, Edinburgh Napier University, 10 Colinton Rd Edinburgh EH10 5DT [email protected] Prepared by: TR Verified by: RL Approved by: JG Status: Confidential Issue no: 1 Date: 25/11/16 Directory & File Name: Status: Draft v2 Issue no: 1 Date: 25/11/16 C:\Users\tom\Desktop\tom1\r esearch\SEStran rts\2016\SEStran Governance Report Edinburgh Napier University TRI Nov 2016.docx Directory & File Name: C:\Documents and Settings\Tombo\My Documents\proposals\Active travel proposal v2.doc TRI Edinburgh Napier University Report for SEStran on PTA models Table of Contents 1. PURPOSE AND STRUCTURE OF THIS REPORT ................................................................ 2 1.1 PURPOSE .......................................................................................................................... 2 1.2 REPORT STRUCTURE ......................................................................................................... 2 2. DIFFERENT FORMS OF (P)TA .............................................................................................. 2 2.1 WHAT IS A MODEL 3 REGIONAL TRANSPORT PARTNERSHIP AND HOW DOES IT DIFFER FROM WHAT SESTRAN IS NOW? ............................................................................................................... 2 2.2 CAPACITY OF RTPS IN SCOTLAND ..................................................................................... -

400 Airport • Ingliston P&R • Gyle • Wester Hailes • Fairmilehead • Moredun • Royal Infirmary • Fort Kinnaird

Real time information Get real-time departures from your local bus stop: TfEapp.com Live service updates are also available online at www.lothianbuses.co.uk 400 Airport • Ingliston P&R • Gyle • Wester Hailes • Fairmilehead • Moredun • Royal Infirmary • Fort Kinnaird Edinburgh Airport — — — — 0540 0610 0640 0718 0748 0818 0853 0923 0953 1453 1523 1553 1623 1650 Ingliston Park & Ride — — — — 0544 0614 0644 0723 0753 0823 0858 0928 0958 1458 1528 1558 1628 1655 RBS Gogarburn — — — — 0548 0618 0648 0727 0758 0828 0903 0932 1002 1502 1532 1603 1633 1700 Gyle Centre — — — — 0552 0622 0653 0732 0805 0835 0909 0937 1007 1507 1537 1609 1639 1706 then Edinburgh Park, Redheughs Ave G G G G 0554 0624 0655 0734 0807 0837 0911 0939 1009 1509 1539 1612 1642 1709 every Westside Plaza 0428 0458 0523 0543 0605 0635 0707 0748 0821 0851 0924 0951 1021 1521 1554 1632 1702 1729 Friday to Monday Clovenstone 0432 0502 0527 0547 0609 0639 0712 0753 0826 0856 0928 0955 1025 30 1525 1558 1636 1706 1733 Oxgangs Bank 0443 0513 0538 0558 0620 0651 0725 0808 0840 0910 0941 1008 1038 1538 1613 1651 1721 1748 mins Kaimes Crossroads 0450 0520 0545 0605 0627 0700 0734 0818 0849 0919 0949 1016 1046 until 1546 1623 1701 1731 1758 Hyvots Bank 0454 0524 0549 0609 0631 0705 0741 0825 0855 0925 0955 1022 1052 1553 1630 1708 1738 1805 Royal Infirmary 0503 0533 0558 0618 0640 0715 0752 0836 0906 0936 1005 1032 1102 1604 1641 1719 1749 1816 Hay Drive 0509 0539 0604 0624 0646 0721 0758 0842 0912 0942 1011 1038 1108 1611 1648 1726 1756 1823 Fort Kinnaird (west) 0512 0542 0607 0627 -

Map Downtown Vancouver

Tourism Vancouver Official Map Downtown Vancouver 1 To North Shore, Whistler, 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Exclusive Discounts Tourism Vancouver Horseshoe Bay Ferry Visitor Centre Lighthouse Accommodation, Sightseeing, Adventure, Terminal & Pemberton Y 200 Burrard Street, through Highway 99 Stanley Park A Brockton Attractions, Entertainment W at Canada Place Way 99 Bus Exchange Vancouver Point Legend Vancouver N Free Reservation & Information Services Aquarium O Rose S Hours of Operation: I EasyPark located at Brockton Totem Tourism Vancouver Visitor Centre Swimming Pool STANLEY S Garden V all parking areas in T Stanley ParkPark Nine 8:30am to 6:00pm Daily A A Oval Poles N O’Clock Stanley Park L Horse Dawn PARK E Malkin Gun Shopping Areas Cruise Ship Terminal A Y Tours A tourismvancouver.com P Bowl Located inside the Tourism Vancouver Visitor Centre A R Hospital Seabus K Hallelujah C A Point Ferguson U Police Helijet Point S E W SkyTrain Station / Bus Exchange Harbour Flight Centre Downtown Vancouver Index A Vancouver Y Rowing Club Lost HMCS Seaside Greenway (Seawall) Aquabus Ferry ACCOMMODATIONS Lagoon Royal Vancouver Discovery Second One way streets False Creek Ferry Pitch Yacht Club Beach 1A Deadman’s & Putt Hotels Hostels Island EasyPark Parking Boat Charters Harbour 1 Auberge Vancouver Hotel C5 71 C & N Backpackers Hostel E7 W Devonian Harbour Cruises N 2 Barclay Hotel C4 72 Hostelling International - G Tennis E Tennis O Park & Events Courts R 3 Best Western Plus Chateau Granville Vancouver Central E4 Courts V E G D R I I O N A Hotel & Suites & Conference Centre E4 73 Hostelling International - B L A G O S B 79 T COAL 4 Best Western Plus Downtown Vancouver E4 Vancouver Downtown E3 E N T 5 Best Western Plus Sands Hotel C2 74 SameSun Backpacker Lodges - A 81 S 82 HARBOUR L O K C 6 Blue Horizon Hotel C4 Vancouver E4 R L 61 A I P H T 7 The Buchan Hotel B3 75 St. -

Golden Ears Bridge Pile Foundations

Naesgaard, E., Amini, A., Uthayakumar, U.M., and Fellenius, B.H., 2012. "Long piles in thick lacustrine and deltaic deposits. Two Bridge Foundation Case Histories." Full-scale Testing in Foundation Design, M.H. Hussein, R.D. Holtz, K.R. Massarsch, and G.E. Likins, eds., Geotechnical Special Publication 227, 404-421. ASCE GeoInstitute Geo-Congress, Oakland March 25-29, 2012, State of the Art and Practice in Geotechnical Engineering, ASCE, Reston, VA. 404 Long Piles in Thick Lacustrine and Deltaic Deposits. Two Bridge Foundation Case Histories Ernest Naesgaard1), PhD., P.Eng., P.E., M.ASCE Ali Amini2), PhD., P.Eng., Uthaya M. Uthayakumar3), PhD., P.Eng. Bengt H. Fellenius4), Dr.Tech., P.Eng., M.ASCE 1)Naesgaard Geotechnical Ltd., RR1 Site I-38, Bowen Island, BC, V0N 1G0 <[email protected]> 2)Naesgaard Geotechnical Ltd., 2547 Shelley Rd., North Vancouver, BC, V7H 1K1 <[email protected]> 3)EXP Services Inc., 7025 Greenwood St., Burnaby, BC, V5A 1X7 <[email protected]> 4)Consulting Engineer, 2475 Rothesay Avenue, Sidney, BC, V8L 2B9 <[email protected]> ABSTRACT. Two recent bridge projects in British Columbia highlight the importance of having well-instrumented pile loading tests as part of piled foundation design. First case is the 1.5 km long, five-lane W.R. Bennett Bridge in the challenging Okanagan Lake soil profile with soft and loose to medium dense silts and silty sands to depths over 100 m. Five 610-mm diameter open- and closed-toe test piles were driven to 45 m depth. Pile dynamics tests were performed for all five test piles and a static loading test was carried out on the center pile, driven closed-toe.