Augustine's Confessions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY of AMERICA Doctrina Christiana

THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF AMERICA Doctrina Christiana: Christian Learning in Augustine's De doctrina christiana A DISSERTATION Submitted to the Faculty of the Department of Medieval and Byzantine Studies School of Arts and Sciences Of The Catholic University of America In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree Doctor of Philosophy © Copyright All Rights Reserved By Timothy A. Kearns Washington, D.C. 2014 Doctrina Christiana: Christian Learning in Augustine's De doctrina christiana Timothy A. Kearns, Ph.D. Director: Timothy B. Noone, Ph.D. In the twentieth century, Augustinian scholars were unable to agree on what precisely the De doctrina christiana is about as a work. This dissertation is an attempt to answer that question. I have here employed primarily close reading of the text itself but I have also made extensive efforts to detail the intellectual and social context of Augustine’s work, something that has not been done before for this book. Additionally, I have put to use the theory of textuality as developed by Jorge Gracia. My main conclusions are three: 1. Augustine intends to show how all learned disciplines are subordinated to the study of scripture and how that study of scripture is itself ordered to love. 2. But in what way is that study of scripture ordered to love? It is ordered to love because by means of such study exegetes can make progress toward wisdom for themselves and help their audiences do the same. 3. Exegetes grow in wisdom through such study because the scriptures require them to question themselves and their own values and habits and the values and habits of their culture both by means of what the scriptures directly teach and by how readers should (according to Augustine) go about reading them; a person’s questioning of him or herself is moral inquiry, and moral inquiry rightly carried out builds up love of God and neighbor in the inquirer by reforming those habits and values out of line with the teachings of Christ. -

Healing Through Humility: an Examination of Augustine's Confessions Catherine Maurer [email protected]

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Northern Michigan University: The Commons Northern Michigan University NMU Commons All NMU Master's Theses Student Works 7-2018 Healing through Humility: An Examination of Augustine's Confessions Catherine Maurer [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.nmu.edu/theses Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Catholic Studies Commons, and the Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Maurer, Catherine, "Healing through Humility: An Examination of Augustine's Confessions" (2018). All NMU Master's Theses. 561. https://commons.nmu.edu/theses/561 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at NMU Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in All NMU Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of NMU Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. HEALING THROUGH HUMILITY: AN EXAMINATION OF AUGUSTINE’S CONFESSIONS By Catherine G. Maurer THESIS Submitted to Northern Michigan University In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Office of Graduate Education and Research July 2018 © 2018 Catherine G. Maurer SIGNATURE APPROVAL FORM Healing through Humility: An Examination of Augustine’s Confessions This thesis by Catherine G. Maurer is recommended for approval by the student’s Thesis Committee and Department Head in the Department of English and by the Interim Director of Graduate Education and Research. __________________________________________________________ Committee Chair: Dr. Lynn Domina Date __________________________________________________________ First Reader: Dr. David Wood Date __________________________________________________________ Second Reader (if required): Date __________________________________________________________ Department Head: Dr. -

Saint Joseph's College Guide to Citing Theology Resources in MLA Format

This guide was created by Patricia Sodano Ireland, Ph.D., Director, Theology Programs. Saint Joseph’s College Guide to Citing Theology Resources in MLA format The MLA handbook does not provide precise instructions for citing documents of the Church. The following are guidelines for citations in various formats, e.g., print, web, database, etc. A document may be in multiple formats. Cite accordingly. No matter what the format of the source, there are a few “rules of thumb” when it comes to Catholic Church documents. Most papal and episcopal documents are treated as books, not as letters or chapters. This means they are italicized or underlined, rather than put in quotation marks. Do not use online automatic formatting for Catholic Church documents, such as www.easybib.com, as these treat the following as letters or chapters, which is incorrect. Follow the guidelines, and do it yourself. These include the following: Papal encyclicals Papal decrees Council documents (e.g., Vatican II documents) Apostolic letters Apostolic exhortations Anniversary documents commenting on previous encyclical letters Bishops’ statements Primary works (e.g., works of antiquity through the Middle Ages, such as from Irenaeus, Augustine, Aquinas, etc.) While the Catechism of the Catholic Church is treated as a book, a catechetical document is treated as a chapter and put in quotation marks. An example would be the headings: “The Desire for God.” Catechism of the Catholic Church. With regard to papal documents in print or EBook form, indicate the translation or edition you are using in the bibliography. This is not necessary in the citations. -

The Rhetoric(S) of St. Augustine's Confessions

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Communication Scholarship Communication 2008 The Rhetoric(s) of St. Augustine's Confessions James M. Farrell University of New Hampshire, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/comm_facpub Part of the Christianity Commons, Classical Literature and Philology Commons, Ethics in Religion Commons, History of Christianity Commons, Medieval History Commons, Medieval Studies Commons, and the Rhetoric Commons Recommended Citation James M. Farrell, "The Rhetoric(s) of St. Augustine's Confessions," Augustinian Studies 39:2 (2008), 265-291. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Communication at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Communication Scholarship by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Rhetoric(s) of St. Augustine’s Confessions. James M. Farrell University of New Hampshire Much of the scholarship on Augustine’s Confessions has consigned the discipline of rhetoric to the margins. Rhetoric was Augustine’s “major” in school, and his bread and bacon as a young adult. But in turning to God in the garden at Milan, Augustine also turned away from his profession. Rightly so, the accomplishment of Augustine’s conversion is viewed as a positive development. But the conversion story also structures the whole narrative of the Confessions and thus rhetoric is implicated in that narrative. It is the story of “Latin rhetorician turned Christian bishop.”1 Augustine’s intellectual and disciplinary evolution is mapped over a story of spiritual ascent. -

Knowing Doing

KNOWING OING &D. C S L EWI S I N S TITUTE PROFILE IN FAITH “Servant of the Servants of God” Monica by David B. Calhoun Professor Emeritus of Church History Covenant Theological Seminary, St. Louis, Missouri This article originally appeared in the Fall 2012 issue of Knowing & Doing. ugustine wrote his Confessions when Her name, Monica, probably he was about forty-three years old, had Berber origins. The Berbers A after he had become bishop of Hippo (in were the earliest known inhab- modern-day Algeria). In that autobiographical ac- itants of the western Mediter- count he tells the story of his first thirty-three ranean coast of Africa.7 As for years—his birth, childhood, rebellious youth, am- many coastal Berbers, her cul- bition, travel to Rome and Milan, conversion, his ture was Latin. She was born mother’s joining him in Italy, their time together in into a believing household and Cassiciacum, their return journey south to North brought up in the teachings David B. Calhoun Africa, and his mother’s death en route at Ostia on and practice of the second-cen- the Tiber. Peter Brown writes, “What Augustine tury African church. From her childhood she devel- remembered in the Confessions was his inner life; oped within her own family something of a “saintly” and this inner life is dominated by one figure— reputation. But on one occasion at least she almost lost his mother.”1 it. The story lived on, and, perhaps like all good sto- Augustine wrote Confessions some ten years after ries, improved with the telling. -

St. Augustine on Time

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Vol. 6, No. 6; June 2016 St. Augustine on Time William Alexander Hernandez University of Houston 4800 Calhoun Rd. Houston, TX 77004 United States Abstract In Book XI of the Confessions (397), St. Augustine explores the nature of time. John L. Morrison argues that in Book XI of the Confessions, St. Augustine puts forth a subjective account of time. On this view, time exists within the human mind. I am in considerable agreement with Morrison’s interpretation of the Confession XI. However, I will argue that in On Genesis (388-389), Augustine develops an objective account of time. This means that time is a creature of God and so exists before human consciousness. It seems that Augustine has two accounts of time, one objective and the other subjective. Key Words: Time, God, Augustine, Creation, Phenomenon of Human Consciousness. Introduction In On Genesis (389) and in Book XI of The Confessions (397), St. Augustine explores the nature of time. Augustine writes, “What then is time? If no one asks me, I know; if I want to explain it to a questioner, I do not know” (Augustine 2006, p. 242). Time is a concept that we appear to understand, but once we endeavor to explain time itself, it gives rise to paradoxes. Augustine’s exploration of time is part of his larger reflections on God’s creation of the universe1. Augustine examines time in the context of scriptural interpretation of Genesis and other books of the Old Testament. Consequently, Augustine’s account of time is influenced by the Bible. -

Introduction to De Doctrina Christiana St

Summer Institute Dallas Baptist University in Christian Scholarship Dr. Davey Naugle Introduction to De Doctrina Christiana St. Augustine (354-430) I. Aim and Circumstances 1. Augustine spent half his life in philosophical and rhetorical studies and there is a great deal of the ancient school master and professor in Augustine--a conviction of the importance of detail, devotion to consistency of interpretation, reverence for canonical texts as authorities, esp. Scripture, and to a lesser extent, classic texts from antiquity. Augustine owed a lot to his former training and career. In DDC, the old education and his proposals for a distinctively Christian one meet. It is where the ancient liberal tradition or classical culture meets Christianity and is modified, elevated, and reformed for Christian purposes. 2. The purpose of DDC, on which Augustine worked for some 30 years, is to systematize for the benefit of others, especially young preachers as well as laity, the observations and principles that had become apparent to him in his study of the Bible and to enable readers of it to be their own interpreters. He wishes to provide fundamental instructions so one may pick up the Bible and read it wisely. He wants to help Christians learn from the Bible. 3. The title of the book indicates that it applies to the task of teaching Christianity first to oneself and then to others. It also embraces the basic teachings of Christianity (mere Christianity) which can be drawn from Scripture. See also here his Enchiridion (Handbook). DDC is a guide to the discovery and communication of what is taught in the Bible. -

CATH 370: the Confessions of Saint Augustine 1/9

*Cover of Confessions, trans. Thomas Williams, Hackett Publishing Company, 2019. “I am resolved to make truth in my heart before [God] in my confession, and to make truth in my writing before many witnesses” (Augustine, Confessions 10.1) What does the truth of confession make of Augustine, and what does it make of us, his witnesses? This course charts Augustine’s adaptation of the classical heroic ideal in the Confessions and the role of praise (confession) in the metamorphosis of the Christian hero’s odyssey. CATH 370: The Confessions of Saint Augustine 1/9 CATH 370: TOPICS IN CATHOLIC STUDIES The Confessions of Saint Augustine Winter 2021 Tues. & Thurs.: 2.35 pm-3.55 pm (Virtual/Zoom) Instructor: Pablo Irizar, PhD Email: [email protected] Virtual Office Hours: By appointment only. A. Course Description B. Requirements and Objectives C. Reading & Lecture Schedule D. Course Schedule E. Assignments and Evaluations F. Policies, Rights and Responsibilities G. Selected Bibliography H. Online Resources I. Some Student Wellness Resources A. COURSE DESCRIPTION This course introduces the Confessions of Saint Augustine, a monumental 4th century Christian figure. Augustine famously wrote, ‘I am resolved to make truth in my heart before [God] in my confession, and to make truth in my writing before many witnesses’ (conf. 10.1). What does the truth of confession make of Augustine and what does it make of us, his witnesses? This course charts the (re)making of the classical heroic ideal in the Confessions and the role of praise (confession) in the metamorphosis of the Christian hero. To this end, we shall read Augustine carefully by deploying a comprehensive approach of analysis, according to three axes of interpretation: contextual, intercontextual and systematic. -

Confessions, by Augustine

1 AUGUSTINE: CONFESSIONS Newly translated and edited by ALBERT C. OUTLER, Ph.D., D.D. Updated by Ted Hildebrandt, 2010 Gordon College, Wenham, MA Professor of Theology Perkins School of Theology Southern Methodist University, Dallas, Texas First published MCMLV; Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 55-5021 Printed in the United States of America Creator(s): Augustine, Saint, Bishop of Hippo (345-430) Outler, Albert C. (Translator and Editor) Print Basis: Philadelphia: Westminster Press [1955] (Library of Christian Classics, v. 7) Rights: Public Domain vid. www.ccel.org 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction . 11 I. The Retractations, II, 6 (A.D. 427) . 22 Book One . 24 Chapter 1: . 24 Chapter II: . 25 Chapter III: . 25 Chapter IV: . 26 Chapter V: . 27 Chapter VI: . 28 Chapter VII: . 31 Chapter VIII: . 33 Chapter IX: . 34 Chapter X: . 36 Chapter XI: . 37 Chapter XII: . 39 Chapter XIII: . 39 Chapter XIV: . 41 Chapter XV: . 42 Chapter XVI: . 42 Chapter XVII: . 44 Chapter XVIII: . 45 Chapter XIX: . 47 Notes for Book I: . 48 Book Two . .. 50 Chapter 1: . 50 Chapter II: . 50 Chapter III: . 52 Chapter IV: . 55 Chapter V: . 56 Chapter VI: . 57 Chapter VII: . 59 Chapter VIII: . 60 Chapter IX: . .. 61 3 Chapter X: . 62 Notes for Book II: . 63 Book Three . .. 64 Chapter 1: . 64 Chapter II: . 65 Chapter III: . 67 Chapter IV: . 68 Chapter V: . 69 Chapter VI: . 70 Chapter VII: . 72 Chapter VIII: . 74 Chapter IX: . .. 76 Chapter X: . 77 Chapter XI: . 78 Chapter XII: . 80 Notes for Book III: . 81 Book Four . 83 Chapter 1: . 83 Chapter II: . 84 Chapter III: . -

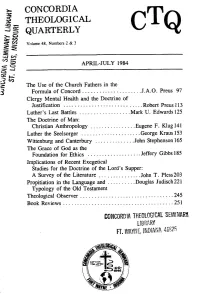

The Use of the Church Fathers in the Formula of Concord

CONCORDIA THEOLOGICAL QUARTERLY Volume 48. Numbers 2 & 3 APRIL-JULY 1984 The Use of the Church Fathers in the Formula of Concord .....................J.A.O. Preus 97 Clergy Mental Health and the Doctrine of Justification ............................Robert Preus 1 13 Luther's Last Battles ..................Mark U. Edwards 125 The Doctrine of Man: Christian Anthropology ................Eugene F. Klug 14 1 Luther the Seelsorger .....................George Kraus 153 Wittenburg and Canterbury ............. .John Stephenson 165 The Grace of God as the Foundation for Ethics ....... ............Jeffery Gibbs 185 Implications of Recent Exegetical Studies for the Doctrine of the Lord's Supper: A Survey of the Literature ... ............John T. Pless 203 Propitiation in the Language and ..........Douglas Judisch 22 1 Typology of the Old Testament Theological Observer .................................245 Book Reviews .......................................251 The Use of the Church Fathers in the Formula of Concord J.A.O. Preus The use of the church fathers in the Formula of Concord reveals the attitude of the writers of the Formula to Scripture and to tradition. The citation of the church fathers by these theologians was not intended to override the great principle of Lutheranism, which was so succinctly stated in the Smalcalci Ar- ticles, "The Word of God shall establish articles of faith, and no one else, not even an angel" (11, 2.15). The writers of the Formula subscribed wholeheartedly to Luther's dictum. But it is also true that the writers of the Formula, as well as the writers of all the other Lutheran Confessions, that is, Luther and Melanchthon, did not look upon themselves as operating in a theological vacuum. -

Encounters with God in Augustine's Confessions

1 The Philosophical Conversion (Book VII) In Book VII of the Confessions, Augustine focuses his attention on the concept of God and considers his need for a mediator. In between, he struggles with the problem of evil and finds the pathway that leads to his intellectual conversion. Though the young philosopher has freed himself from dualism and has become convinced that God is incorruptible, he is still unable to conceive of a spiritual substance or to speak about God except as a being extended in space. Yet after he reads certain books of the Platonists, a vision of God enables him to overcome these problems,1 permits him to make a constructive response to the problem of evil, and helps him under- stand why he needs a mediator between God and the soul. The Neoplatonic vision in which Augustine participates is both an existential and an intellectual episode. From an existential point of view, it allows him to climb a Neoplatonic ladder from the visible to the invisible, see an unchangeable light, respond when God calls out to him from afar, and catch a glimpse of a spiritual substance that stands over against him. From an intellectual perspective, this same experience helps him understand why a spiritual substance cannot be conceived in spa- tiotemporal terms, teaches him that figurative discourse is necessary for making access to it, convinces him that the evil he fears is not a sub- stance, and shows him that corruption is both a privation of the good and a perversion of the will. In this chapter, we begin with the problem of framing an adequate concept of God and turn to Augustine’s struggles with the problem of evil. -

What Luther Learned from the Early Church and the Fathers

Perichoresis Volume 17.4 (2019): 41–56 DOI: 10.2478/perc-2019-0027 THE DAUGHTER OF THE WORD: WHAT LUTHER LEARNED FROM THE EARLY CHURCH AND THE FATHERS GLEN L. THOMPSON* Asia Lutheran Seminary ABSTRACT. All the major sixteenth-century Reformers knew something about the early church and used the early Fathers. As an Augustinian monk and professor of theology, howev- er, Luther’s knowledge and use of the great Father was both deeper and more nuanced. While indebted to Augustine, Luther went further in defining what it meant for theology to be ‘scrip- tural’. He saw history as the interaction of God’s two regimes, and the church of every age as weak and flawed but conquering through the cross of Christ. This led him to a free use of the Fathers without being constrained to always agree with or imitate them. The comfort he re- ceived from the Apostles’ Creed in particular led him to appreciate the early creedal state- ments, and so it was natural for him to use them as models when formulating the new confes- sions required in his own day. The sixteenth-century heritage of written confessions of faith is a heritage under-appreciated but still vital for church bodies today.1 KEYWORDS: Luther, Augustine, Church Fathers, History, Creeds, Confessions Ecclesia enim est filia, nata ex verbo, non est mater verbi. ‘For the Church is the daughter born from the Word; she is not the mother of the Word.’ Luther, Lecture on Genesis 7:17-24 (AE 2: 101; WA 42: 334) In January of 1505, the 21-year old Martin Luther was promoted to Master of Arts at the University of Erfurt.