Synaesthetic Dress: Episodes of Sensational Objects in Performance Art, 1955-1975

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Heiser, Jörg. “Do It Again,” Frieze, Issue 94, October 2005

Heiser, Jörg. “Do it Again,” Frieze, Issue 94, October 2005. In conversation with Marina Abramovic Marina Abramovic: Monica, I really like your piece Hausfrau Swinging [1997] – a video that combines sculpture and performance. Have you ever performed this piece yourself? Monica Bonvicini: No, although my mother said, ‘you have to do it, Monica – you have to stand there naked wearing this house’. I replied, ‘I don’t think so’. In the piece a woman has a model of a house on her head and bangs it against a dry-wall corner; it’s related to a Louise Bourgeois drawing from the ‘Femme Maison’ series [Woman House, 1946–7], which I had a copy of in my studio for a long time. I actually first shot a video of myself doing the banging, but I didn’t like the result at all: I was too afraid of getting hurt. So I thought of a friend of mine who is an actor: she has a great, strong body – a little like the woman in the Louise Bourgeois drawing that inspired it – and I knew she would be able to do it the right way. Jörg Heiser: Monica, after you first showed Wall Fuckin’ in 1995 – a video installation that includes a static shot of a naked woman embracing a wall, with her head outside the picture frame – you told me one critic didn’t talk to you for two years because he was upset it wasn’t you. It’s an odd assumption that female artists should only use their own bodies. -

Envisioning Cyborg Hybridity Through Performance Art: a Case Study of Stelarc and His Exploration of Humanity in the Digital Age Cara Hunt

Vassar College Digital Window @ Vassar Senior Capstone Projects 2015 Envisioning Cyborg Hybridity Through Performance Art: A Case Study of Stelarc and His Exploration of Humanity in the Digital Age Cara Hunt Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalwindow.vassar.edu/senior_capstone Recommended Citation Hunt, Cara, "Envisioning Cyborg Hybridity Through Performance Art: A Case Study of Stelarc and His Exploration of Humanity in the Digital Age" (2015). Senior Capstone Projects. Paper 400. This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Window @ Vassar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of Digital Window @ Vassar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Envisioning Cyborg Hybridity Through Performance Art: A Case Study of Stelarc and His Exploration of Humanity in the Digital Age Cara Hunt Advisors: Janet Gray & Ken Livingston Spring 2015 Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a major in the program in Science, Technology, and Society (STS) ABSTRACT In this paper I argue that artistic representation has historically been and continues to be a valuable medium for envisioning new bodily forms and for raising important questions regarding changes in what it means to be human in an era of rapid technological advancement. I make this claim using Stelarc, an eccentric Australian performance artist, as a case study. Stelarc’s artistic exploration of the modern-day cyborg enacts and represents philosophical and ontological concepts such as identity, hybridity, and embodiment that are subject to change in the digital age. In order to arrive at this claim, Chapter 1 will trace the cyborg back to its use in 20th century Dada art. -

Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018

The Journal of Dress History Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018 Front Cover Image: Textile Detail of an Evening Dress, circa 1950s, Maker Unknown, Middlesex University Fashion Collection, London, England, F2021AB. The Middlesex University Fashion Collection comprises approximately 450 garments for women and men, textiles, accessories including hats, shoes, gloves, and more, plus hundreds of haberdashery items including buttons and trimmings, from the nineteenth century to the present day. Browse the Middlesex University Fashion Collection at https://tinyurl.com/middlesex-fashion. The Journal of Dress History Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018 Editor–in–Chief Jennifer Daley Editor Scott Hughes Myerly Proofreader Georgina Chappell Published by The Association of Dress Historians [email protected] www.dresshistorians.org The Journal of Dress History Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018 [email protected] www.dresshistorians.org Copyright © 2018 The Association of Dress Historians ISSN 2515–0995 Online Computer Library Centre (OCLC) accession #988749854 The Journal of Dress History is the academic publication of The Association of Dress Historians through which scholars can articulate original research in a constructive, interdisciplinary, and peer reviewed environment. The Association of Dress Historians supports and promotes the advancement of public knowledge and education in the history of dress and textiles. The Association of Dress Historians (ADH) is Registered Charity #1014876 of The Charity Commission for England and Wales. The Journal of Dress History is copyrighted by the publisher, The Association of Dress Historians, while each published author within the journal holds the copyright to their individual article. The Journal of Dress History is circulated solely for educational purposes, completely free of charge, and not for sale or profit. -

The Hong Kong Polytechnic University Subject Description Form

Form AS 140 The Hong Kong Polytechnic University Subject Description Form Please read the notes at the end of the table carefully before completing the form. Subject Code CBS1A20 Subject Title Self-representation in New Media Credit Value 3 Level 1 Pre-requisite / Exclusion Co-requisite/ GEC1A05W Self-representation in New Media Exclusion GEC1A05 Self-representation in New Media CBS1A20M Self-representation in New Media Objectives This subject aims to examine how the emergence of different new media has mediated the conception and production of the self, identity, and autobiography by visual and verbal means. The complex human conditions behind such self-representation from different cultures will be investigated. Intended Learning Upon completion of the subject, students will be able to: Outcomes (a) enhance students’ literacy skills in reading and writing; (Note 1) (b) identify the mediated personal narratives embedded in different types of self-representation in new media; (c) pinpoint the boundary and difference between mere self-expression and performing/advertising the self in new media; (d) analyze how embodied self-expression in new media has transcended traditional means of communication; (e) evaluate critically the merit and limitation of specific forms of self- representation in new media. Subject Synopsis/ 1. Overview about Interpreting Life Narratives in Different Media (1 Indicative Syllabus lecture) (Note 2) 2. Self-representation in Self-portraiture: Identity Construction (2 lectures) Vermeer, Velasquez, Rembrandt, Kathe Kollwitz, Courbet, Cèzanne, Van Gogh, Toulouse Lautrec, Charlotte Salomon, Picasso, Dali, Magritte, Egon Schiele, Frida Kahlo, Francis Bacon, Orlan, Ana Mendieta, Adrian Piper, Yu Hong, Fang Lijun, & Yue Minjun, Song Dong & Wilson Shieh 3. -

The Inflation of Abstraction | the New Yorker

6/10/2019 The Inflation of Abstraction | The New Yorker The Art World The Inflation of Abstraction The Met’s show of Abstract Expressionism wants to remake the canon. By Peter Schjeldahl December 31, 2018 https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2019/01/07/the-inflation-of-abstraction 1/8 6/10/2019 The Inflation of Abstraction | The New Yorker Mark Rothko’s “No. 3,” from 1953, his peak year of miracles. © 1998 Kate Rothko Prizel & Christopher Rothko / Courtesy ARS he rst room of “Epic Abstraction: Pollock to Herrera,” a wishfully canon- T expanding show of painting and sculpture from the past eight decades, at the Metropolitan Museum, affects like a mighty organ chord. It contains the museum’s two best paintings by Jackson Pollock: “Pasiphaë” (1943), a quaking compaction of https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2019/01/07/the-inflation-of-abstraction 2/8 6/10/2019 The Inflation of Abstraction | The New Yorker mythological elements named for the accursed mother of the Minotaur, and “Autumn Rhythm (Number 30)” (1950), a singing orchestration of drips in black, white, brown, and teal enamel—bluntly material and, inextricably, sublime. There are six Pollock drawings, too, and “Number 7” (1952), one of his late, return-to- guration paintings in mostly black on white, of an indistinct but hieratic head. The adjective “epic” does little enough to honor Pollock’s mid-century glory, which anchors the standard art-historical saga of Abstract Expressionism—“The Triumph of American Painting,” per the title of a 1976 book on the subject by Irving Sandler —as a revolution that stole the former thunder of Paris and set a stratospheric benchmark for subsequent artists. -

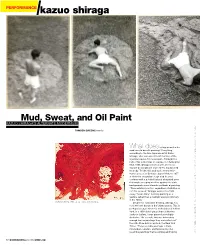

Performance Kazuo Shiraga

PERFORMANCE kazuo shiraga Mud, Sweat, and Oil Paint KAZUO SHIRAGA’S ALTERNATE MODERNIsm. TAMSEN GREENEwords What does rolling around in the mud have to do with painting? Everything, according to the late Japanese artist Kazuo Shiraga, who was a prominent member of the legendary Gutai Art Association. Although the bulk of his output was on canvas, in Challenging Mud, 1955, Shiraga wrestled with a formless mixture of wall plaster and cement that bruised his body. To him, this and such other perfor- mance pieces as Sanbaso-Super Modern, 1957— in which he swayed on stage clad in a red costume with a pointed hat and elongated arms that made sweeping motions against the dark background—were alternate methods of painting. “There exists my action, regardless of whether or not it is secured,” Shiraga wrote in his 1955 essay “Action Only.” Defining painting as a gesture rather than a medium was revolutionary in the 1950s. Chizensei Kirenji, 1961. OIL ON CANVAS, 51¼ X 63¾ IN. Despite his innovative thinking, Shiraga has not been well known in the United States. This is perhaps because when his work debuted in New York, in a 1958 Gutai group show at Martha Jackson Gallery, it was panned as multiply derivative. “As records, they are interesting enough, but as paintings they are ineffectual,” the critic Dore Ashton wrote in the New York Times. “They resemble paintings in Paris, Amsterdam, London, and Mexico City that resemble paintings that resemble paintings by FROM TOP: THREE IMAGES, AMAGASAKI CULTURAL CENTER; VERVOORDT FOUNDATION COLLECTION. OPPOSITE: BOTH IMAGES, AMAGASAKI CULTURAL CENTER 32 MODERN PAINTERS APRIL 2010 ARTINFO.COM Performance stills from Challenging Mud, third execution. -

Vital Series, Mallets

USER MANUAL Produced by Vir2 Instruments 00 Vir2 Instruments is an international team of sound designers, musicians, and programmers who specialize in creating the world’s most advanced virtual instrument libraries. Vir2 is producing the instruments that shape the sound of modern music. 29033 Avenue Sherman, Suite 201 Valencia, CA 91355 Phone:661.295.0761 Web:www.vir2.com 00 MALLETS/ TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 01: INTRODUCTION TO THE LIBRARY 01 INTRODUCTION TO THE LIBRARY TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE CHAPTER 02: REQUIREMENTS AND INSTALLATION 02 SYSTEM REQUIREMENTS INSTALLING IN KONTAKT INSTALLING IN KOMPLETE KONTROL & MASCHINE AUTHORIZING UPDATING CHAPTER 03: USING KONTAKT 05 HOW TO ACCESS THE MALLETS LIBRARY FROM KONTAKT USING KONTAKT IN STANDALONE MODE USING KONTAKT WITH YOUR D.A.W. USING KONTAKT WITH ANOTHER HOST CHAPTER 04: GETTING STARTED WITH MALLETS 09 MALLETS OVERVIEW INSTRUMENT CONTROLS INSTRUMENTS TURNED ON VS INSTRUMENTS TURNED OFF GLOBAL FILTER TUNE ROLLS LFO CONTROLS EFFECTS TECHNICAL SUPPORT, ETC. 13 TECH SUPPORT FULL VERSION OF KONTAKT 5 LICENSE AGREEMENT CREDITS 14 CREDITS CHAPTER 01 01 02 MALLETS/ INTRODUCTION TO THE LIBRARY Thank you for purchasing Mallets. / INTRODUCTION TO THE LIBRARY / INTRODUCTION TO Vir2 Instruments is proud to present the first instrument in our Vital Series, Mallets. Mallets brings users a collection of highly detailed, mallet-based instruments, and places them all in an intuitive instrument for the Kontakt CHAPTER 01 Player. Offering multiple mallet types for the Marimba, Xylophone, Glockenspiel, Tubular Bells, Glass Marimba, Song Bells, Vibraphone, and Crotales, Mallets is extremely versatile. Furthermore, each of the aforementioned instruments are available within one single instance of the instrument, allowing for the layering of each instrument for the exploration of endless tonal color. -

The Performance Art of Marina Abramovic As a Transformational Experience

Psychology, 2018, 9, 1329-1339 http://www.scirp.org/journal/psych ISSN Online: 2152-7199 ISSN Print: 2152-7180 The Performance Art of Marina Abramovic as a Transformational Experience Lília Simões, Maria Consuêlo Passos Department of Postgraduate in Clinical Psychology, Pontifical Catholic University of Pernambuco, Curitiba, Brazil How to cite this paper: Simões, L., & Abstract Passos, M. C. (2018). The Performance Art of Marina Abramovic as a Transformation- Based on issues raised by the autobiographical memoirs of the performing al Experience. Psychology, 9, 1329-1339. artist Marina Abramovic, this article seeks to discuss the transformative po- https://doi.org/10.4236/psych.2018.96081 tential of her work, based on the analysis of six selected performances in Received: April 23, 2018 which the artist uses the body as an object of her art, exploring as a means of Accepted: June 25, 2018 expression of physical limits, exhaustion of the mind and relationship with the Published: June 28, 2018 public. Our objective is to investigate how the artist appropriates the perfor- mance space to discuss through psychoanalytic theory the ritualistic and Copyright © 2018 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc. transformative dimension of her work. Using the field concepts of Antonino This work is licensed under the Creative Ferro and transformational object of Cristopher Bollas. Finally we propose an Commons Attribution International analogy between the space of performance as the analytical field, the perfor- License (CC BY 4.0). mance and the relationship with the public proposing a transformative aes- http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ thetic experience. Open Access Keywords Art, Performance, Field, Transformational, Psychoanalysis 1. -

Selective Analysis of 20Th Century Contemporary Percussion Ensembles Designated for Three Or More Players

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1968 Selective analysis of 20th century contemporary percussion ensembles designated for three or more players Raymond Francis Lindsey The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Lindsey, Raymond Francis, "Selective analysis of 20th century contemporary percussion ensembles designated for three or more players" (1968). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 3513. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/3513 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A SELECTIVE ANALYSIS OF 2 0 ^ CENTURY CONTEMPORARY PERCUSSION ENSEMBLES DESIGNATED FOR THREE OR MORE PLAYERS by Raymond Francis Lindsey B.M* University of Montana 1965 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music University of Montana 1968 Approved by; L L u ' ! JP. 4 . Chairman, Board of Exami4/ers Deah/, Graduate School 1 :: iosa Date UMI Number: EP35093 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. -

Dragon Magazine #217

Issue #217 Vol. XIX, No. 12 May 1995 Publisher TSR, Inc. Associate Publisher Brian Thomsen SPECIAL ATTRACTIONS Editor-in-Chief Boons & Benefits Larry Granato Kim Mohan 10 Compensate your PCs with rewards far more Associate editor valuable than mere cash or jewels. Dale A. Donovan Behind Enemy Lines Phil Masters Fiction editor 18 The PCs are trapped in hostile territory with an Barbara G. Young entire army chasing them. Sounds like fun, doesnt it? Editorial assistant Two Heads are Better than One Joshua Siegel Wolfgang H. Baur 22 Michelle Vuckovich Split the game masters chores between two people. Art director Class Action Peter C. Zelinski Larry W. Smith 26 How about a party of only fighters, thieves, clerics, or mages? Production Renee Ciske Tracey Isler REVIEWS Subscriptions Janet L. Winters Eye of the Monitor Jay & Dee 65 Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery. U.S. advertising Cindy Rick The Role of Books John C. Bunnell 86 Delve into these faerie tales for all ages. U.K. correspondent and U.K. advertising Carolyn Wildman DRAGON® Magazine (ISSN 1062-2101) is published Magazine Marketing, Tavistock Road, West Drayton, monthly by TSR, inc., 201 Sheridan Springs Road, Middlesex UB7 7QE, United Kingdom; telephone: Lake Geneva WI 53147, United States of America. The 0895-444055. postal address for all materials from the United States Subscriptions: Subscription rates via second-class of America and Canada except subscription orders is: mail are as follows: $30 in U.S. funds for 12 issues DRAGON® Magazine, 201 Sheridan Springs Road, sent to an address in the U.S.; $36 in U.S. -

Destabilizing the Sign: the Collage Work of Ellen Gallagher, Wangechi Mutu, and Mickalene Thomas”

“Destabilizing the Sign: The Collage Work of Ellen Gallagher, Wangechi Mutu, and Mickalene Thomas” A Thesis submitted to the Art History Faculty of the College of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning University of Cincinnati In candidacy for the degree of Masters of Arts in Art History Committee Members: Dr. Kimberly Paice (chair) Dr. Morgan Thomas Dr. Susan Aberth April 2013 by: Kara Swami B.A. May 2011, Bard College ABSTRACT This study focuses on the collage work of three living female artists of the African diaspora: Ellen Gallagher (b. 1965), Wangechi Mutu (b. 1972), and Mickalene Thomas (b. 1971). As artists dealing with themes of race and identity, the collage medium provides a site where Gallagher, Mutu, and Thomas communicate ideas about black visibility and representation in our postmodern society. Key in the study is theorizing the semiotic implications in their work, and how these artists employ cultural signs as indicators of identity that are mutable. Ellen Gallagher builds many of her collages on found magazine pages advertising wigs for black women in particular. She defaces the content of these pages by applying abstracted body parts, such as floating eyes and engorged lips, borrowed from black minstrel imagery. Through a process of abstraction and repetition, Gallagher exposes the arbitrariness of the sign—a theory posed by Ferdinand de Sausurre’s semiotic principles—and thereby destabilizes supposed fixity of racial imagery. Wangechi Mutu juxtaposes fragmented images from media sources to construct hybridized figures that are at once beautiful and grotesque. Mutu’s hybrid figures and juxtaposition of disparate images reveal the versatility of the sign and question essentialism. -

The First Gutai Exhibition I N Japan Marks the Dissemination Of

1955a The first Gutai exhibition in Japan marks the dissemination of modernist art through the media and its reinterpretation by artists outside the United States and Europe, also exemplified by the rise of the Neoconcretist group in Brazil. n the fifth issue of the journal Gutai, published in October 1956, painter-his works then were competent yet rather provincial .l this brief statement appeared: 'The US artist jackson Pollock, versions of European postwar abstraction. It is not so much his whom we highly esteemed, has passed away all too early in a road own art as his independence of mind, his defianceof bureaucracy, accident, and we are deeply touched. B. H. Friedman who was close his willingness to seize the opportunity of a clean slate afforded by to him, and who sent us the news of this death, wrote: 'When the historical situation of postwar japan, and his encouragements recently I looked through Pollock's library, I discovered issues two to be as radical as possible that explain the attraction he exerted on and three of Gutai. I was told that Pollock was an enthusiastic artists who were a generation younger. His interest in perfor- disciple of the Gutai, fo r in it he had recognized a vision and a mance and in the theater-the only domain where he was as CD reali� close to his own.' " This last sentence is subject to doubt, to innovative as the other members of Gutai-also played a major U1 0 say the least (was Friedman excessively polite, was his letter tam role in defining the group's activity.