The Evolution of the Modern Clarinet: 1800-1850

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Evolution of the Clarinet and Its Effect on Compositions Written for the Instrument

Columbus State University CSU ePress Theses and Dissertations Student Publications 5-2016 The Evolution of the Clarinet and Its Effect on Compositions Written for the Instrument Victoria A. Hargrove Follow this and additional works at: https://csuepress.columbusstate.edu/theses_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Hargrove, Victoria A., "The Evolution of the Clarinet and Its Effect on Compositions Written for the Instrument" (2016). Theses and Dissertations. 236. https://csuepress.columbusstate.edu/theses_dissertations/236 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Publications at CSU ePress. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CSU ePress. THE EVOLUTION OF THE CLARINET AND ITS EFFECT ON COMPOSITIONS WRITTEN FOR THE INSTRUMENT Victoria A. Hargrove COLUMBUS STATE UNIVERSITY THE EVOLUTION OF THE CLARINET AND ITS EFFECT ON COMPOSITIONS WRITTEN FOR THE INSTRUMENT A THESIS SUBMITTED TO HONORS COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE HONORS IN THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF MUSIC SCHWOB SCHOOL OF MUSIC COLLEGE OF THE ARTS BY VICTORIA A. HARGROVE THE EVOLUTION OF THE CLARINET AND ITS EFFECT ON COMPOSITIONS WRITTEN FOR THE INSTRUMENT By Victoria A. Hargrove A Thesis Submitted to the HONORS COLLEGE In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Honors in the Degree of BACHELOR OF MUSIC PERFORMANCE COLLEGE OF THE ARTS Thesis Advisor Date ^ It, Committee Member U/oCWV arcJc\jL uu? t Date Dr. Susan Tomkiewicz A Honors College Dean ABSTRACT The purpose of this lecture recital was to reflect upon the rapid mechanical progression of the clarinet, a fairly new instrument to the musical world and how these quick changes effected the way composers were writing music for the instrument. -

2019 Preview Notes • Week Two • Persons Auditorium

2019 Preview Notes • Week Two • Persons Auditorium Saturday, July 20 at 8:00pm Flute Quartet in D Major, K. 285 (1777-78) Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Born January 27, 1756 • Died December 5, 1791 Duration: approx. 15 minutes Last Marlboro performance: 2011 When Mozart was just a few years younger than the junior participants in this group, he travelled throughout Europe with his mother in search of employment. While in Mannheim on his way to Paris, he met a Dutch merchant named Willem van Britten Dejong who happened to be an amateur flute player. Dejong, who had made his fortune in India, was happy to commission three concertos and three quartets for his instrument. Mozart, who needed the funds, was happy to accept. However, he only completed the quartets and two concertos (one a transcription of a previously-composed oboe concerto) by the time he left Mannheim. What he did write, though, charmingly showcases the flute. In this quartet, that instrument takes the lead throughout a buoyant Allegro beginning, a delicate Adagio accompanied by sparkling plucking from the strings, and a boisterous but well-balanced Rondo conclusion. Participants: Giorgio Consolati, flute; Hiroko Yajima, violin; Jordan Bak, viola; Alexander Hersh, cello Octet (2004) Jörg Widmann Born June 19, 1973 • In residence 2008, 2019 Duration: approx. 30 minutes Marlboro Premiere Though Widmann’s Octet features frequent microtones, he admits that the piece is “almost throughout, a tonal piece,” which was “risky to write in 2004.” The instrumentation suggests a clear connection to Schubert’s genre-making octet, and the piece’s central third movement, which is titled Lied ohne Worte, is a plangent nod to the composer who wrote so many Lieder over the course of his short life. -

Musik-Katalog Bassetthorn Bassettklarinette

Musik-Katalog für Bassetthorn (3604 Werke) und Bassettklarinette (189 Werke) von Thomas Graß und Dietrich Demus Stand vom 31.Mai 2020 Ergänzungen und Berichtigungen des Katalogs aus dem Sachbuch: „Das Bassetthorn. Seine Entwicklung und seine Musik“, 2. Aufl. 2004, Hrsg. T. Grass und D. Demus, BOD, ISBN 3-8311-4411-7. [email protected] [email protected] Formatierung und Druckherstellung: Michael Baasner 1 Inhaltsverzeichnis 1. Konzerte mit Solo-Bassetthorn 5 1.1 Solo für ein oder mehrere Bassetthörner und Orchester oder Sinfonisches Blasorchester ........5 1.2 Werke mit Solo-Bassetthorn, weiteren Solo-Instrumenten oder Singstimme und Orchester oder Blasorchester, auch Sinfonie Concertanti .........................................................................13 1.3 Historische Bearbeitungen für Bassetthorn und fälschlich oder fraglich dem Bassetthorn zugeschriebene Solowerke mit Orchester .................................................................................18 2 Kammermusik 19 2.1 Bassetthorn Solo ........................................................................................................................19 Duos 24 2.2 Bassetthorn und Klavier / Cembalo / Orgel / Vibraphon / elektronische Musik / Tape ..............24 2.3 Zwei Bassetthörner ....................................................................................................................34 2.4 Bassetthorn und ein anderes Instrument / Singstimme .............................................................37 2.5 Bassetthorn und Gitarre -

Overture to Oberon Composed from 1825-26 Carl Maria Von Weber Born in Eutin, Germany, November 18, 1786 Died in London, June 5

OVERTURE TO OBERON COMPOSED FROM 1825-26 CARL MARIA VON WEBER BORN IN EUTIN, GERMANY, NOVEMBER 18, 1786 DIED IN LONDON, JUNE 5, 1826 The tragic tale of the composition of Weber’s final opera Oberon is perhaps as interesting as the plot of the opera itself. Dying of consumption at the age of 38, the impoverished Weber felt he could not refuse the offer from English impresario Charles Kemble to compose an opera on the subject of Oberon, King of the Faeries, for the London stage— even though he sensed that the project would be the death of him. “Whether I travel or not, in a year I’ll be a dead man,” he wrote to a friend after he had completed the Oberon score, of his decision to make the trip to England to see the work through to performance. “But if I do travel, my children will at least have something to eat, even if Daddy is dead—and if I don’t go they’ll starve. What would you do in my position?” Both points of Weber’s prediction proved correct: The 12 initial performances of Oberon netted his family a great deal of money; and within a few weeks of the work’s successful premiere in April 1826, the composer collapsed of exhaustion and died. Though the composition of operas had always been the center of Weber’s existence, it was not until the last six years of his life that he had finally been given the opportunity to compose the three stage works that quickly took their place among the masterworks of Romanticism: Der Freischütz, Euryanthe, and Oberon. -

What Handel Taught the Viennese About the Trombone

291 What Handel Taught the Viennese about the Trombone David M. Guion Vienna became the musical capital of the world in the late eighteenth century, largely because its composers so successfully adapted and blended the best of the various national styles: German, Italian, French, and, yes, English. Handel’s oratorios were well known to the Viennese and very influential.1 His influence extended even to the way most of the greatest of them wrote trombone parts. It is well known that Viennese composers used the trombone extensively at a time when it was little used elsewhere in the world. While Fux, Caldara, and their contemporaries were using the trombone not only routinely to double the chorus in their liturgical music and sacred dramas, but also frequently as a solo instrument, composers elsewhere used it sparingly if at all. The trombone was virtually unknown in France. It had disappeared from German courts and was no longer automatically used by composers working in German towns. J.S. Bach used the trombone in only fifteen of his more than 200 extant cantatas. Trombonists were on the payroll of San Petronio in Bologna as late as 1729, apparently longer than in most major Italian churches, and in the town band (Concerto Palatino) until 1779. But they were available in England only between about 1738 and 1741. Handel called for them in Saul and Israel in Egypt. It is my contention that the influence of these two oratorios on Gluck and Haydn changed the way Viennese composers wrote trombone parts. Fux, Caldara, and the generations that followed used trombones only in church music and oratorios. -

Finale Transposition Chart, by Makemusic User Forum Member Motet (6/5/2016) Trans

Finale Transposition Chart, by MakeMusic user forum member Motet (6/5/2016) Trans. Sounding Written Inter- Key Usage (Some Common Western Instruments) val Alter C Up 2 octaves Down 2 octaves -14 0 Glockenspiel D¯ Up min. 9th Down min. 9th -8 5 D¯ Piccolo C* Up octave Down octave -7 0 Piccolo, Celesta, Xylophone, Handbells B¯ Up min. 7th Down min. 7th -6 2 B¯ Piccolo Trumpet, Soprillo Sax A Up maj. 6th Down maj. 6th -5 -3 A Piccolo Trumpet A¯ Up min. 6th Down min. 6th -5 4 A¯ Clarinet F Up perf. 4th Down perf. 4th -3 1 F Trumpet E Up maj. 3rd Down maj. 3rd -2 -4 E Trumpet E¯* Up min. 3rd Down min. 3rd -2 3 E¯ Clarinet, E¯ Flute, E¯ Trumpet, Soprano Cornet, Sopranino Sax D Up maj. 2nd Down maj. 2nd -1 -2 D Clarinet, D Trumpet D¯ Up min. 2nd Down min. 2nd -1 5 D¯ Flute C Unison Unison 0 0 Concert pitch, Horn in C alto B Down min. 2nd Up min. 2nd 1 -5 Horn in B (natural) alto, B Trumpet B¯* Down maj. 2nd Up maj. 2nd 1 2 B¯ Clarinet, B¯ Trumpet, Soprano Sax, Horn in B¯ alto, Flugelhorn A* Down min. 3rd Up min. 3rd 2 -3 A Clarinet, Horn in A, Oboe d’Amore A¯ Down maj. 3rd Up maj. 3rd 2 4 Horn in A¯ G* Down perf. 4th Up perf. 4th 3 -1 Horn in G, Alto Flute G¯ Down aug. 4th Up aug. 4th 3 6 Horn in G¯ F# Down dim. -

Sonata for Clarinet Choir Donald S

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 1962 Sonata for Clarinet Choir Donald S. Lewellen Eastern Illinois University Recommended Citation Lewellen, Donald S., "Sonata for Clarinet Choir" (1962). Masters Theses. 4371. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/4371 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. -SONATA POR CLARINET CHOIR A PAPER PRESENTED TO THE FACULTY OF TILE DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC EASTERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF TIIB REQUIREMENTS FOR IBE DEGREE MASTER OF SCIENCE IN EDUCATION DONALDS. LEWELLEN '""'."'.···-,-·. JULY, 1962' TABLE OF CONTENTS :le Page • • • • • • • . • .. • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • i ile of Contents . .. ii iface ••.•....•...•........••....... •· ...•......•.•...• iii ::tion I ! Orchestra and Band ································· 1 lrinet Choir New Concept of Sound •••••••••••••••••• 2 3.rinet Choir Medium of Musical Expression . .. 2 arinet Choir Instrumentation . 3 ction II nata for Clarinet Choir - Analysis . .. 6 mmary • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 8 bliography ••••.•••••••••••••••••••••••.•••••••••••••• 10 PREFACE The available literature for clarinet choir is quite limited, and much of this literature is an arrangement of orchestral music. -

The Recently Rediscovered Works of Heinrich Baermann by Madelyn Moore Submitted to the Graduate Degree Program in Music And

The Recently Rediscovered Works of Heinrich Baermann By Madelyn Moore Submitted to the graduate degree program in Music and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Music. ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. Eric Stomberg ________________________________ Dr. Robert Walzel ________________________________ Dr. Paul Popiel ________________________________ Dr. David Alan Street ________________________________ Dr. Marylee Southard Date Defended: April 1, 2014 The Dissertation Committee for Madelyn Moore certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: The Recently Rediscovered Works of Heinrich Baermann ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. Eric Stomberg Date approved: April 22, 2014 ii Abstract While Heinrich Baermann was one of the most famous virtuosi of the first half of the nineteenth century and is one of the most revered clarinetists of all time, it is not well known that Baermann often performed works of his own composition. He composed nearly 40 pieces of varied instrumentation, most of which, unfortunately, were either never published or are long out of print. Baermann’s style of playing has influenced virtually all clarinetists since his life, and his virtuosity inspired many composers. Indeed, Carl Maria von Weber wrote two concerti, a concertino, a set of theme and variations, and a quintet all for Baermann. This document explores Baermann’s relationships with Weber and other composers, and the influence that he had on performance practice. Furthermore, this paper discusses three of Baermann’s compositions, critical editions of which were made during the process of this research. The ultimate goal of this project is to expand our collective knowledge of Heinrich Baermann and the influence that he had on performance practice by examining his life and three of the works that he wrote for himself. -

Ron Mcclure • Harris Eisenstadt • Sackville • Event Calendar

NEW YORK FebruaryVANGUARD 2010 | No. 94 Your FREE Monthly JAZZ Guide to the New ORCHESTRA York Jazz Scene newyork.allaboutjazz.com a band in the vanguard Ron McClure • Harris Eisenstadt • Sackville • Event Calendar NEW YORK We have settled quite nicely into that post-new-year, post-new-decade, post- winter-jazz-festival frenzy hibernation that comes so easily during a cold New York City winter. It’s easy to stay home, waiting for spring and baseball and New York@Night promising to go out once it gets warm. 4 But now is not the time for complacency. There are countless musicians in our fair city that need your support, especially when lethargy seems so appealing. To Interview: Ron McClure quote our Megaphone this month, written by pianist Steve Colson, music is meant 6 by Donald Elfman to help people “reclaim their intellectual and emotional lives.” And that is not hard to do in a city like New York, which even in the dead of winter, gives jazz Artist Feature: Harris Eisenstadt lovers so many choices. Where else can you stroll into the Village Vanguard 7 by Clifford Allen (Happy 75th Anniversary!) every Monday and hear a band with as much history as the Vanguard Jazz Orchestra (On the Cover). Or see as well-traveled a bassist as On The Cover: Vanguard Jazz Orchestra Ron McClure (Interview) take part in the reunion of the legendary Lookout Farm 9 by George Kanzler quartet at Birdland? How about supporting those young, vibrant artists like Encore: Lest We Forget: drummer Harris Eisenstadt (Artist Feature) whose bands and music keep jazz relevant and exciting? 10 Svend Asmussen Joe Maneri In addition to the above, this month includes a Lest We Forget on the late by Ken Dryden by Clifford Allen saxophonist Joe Maneri, honored this month with a tribute concert at the Irondale Center in Brooklyn. -

The Rise and Fall of the Bass Clarinet in a the RISE and FALL of the BASS CLARINET in A

Keith Bowen - The rise and fall of the bass clarinet in A THE RISE AND FALL OF THE BASS CLARINET IN A Keith Bowen The bass clarinet in A was introduced by Wagner in Lohengrin in 1848. Unlike the bass instruments in C and Bb, it is not known to have a history in wind bands. Its appearance was not, so far as is known, accompanied by any negotiations with makers. Over the next century, it was called for by over twenty other composers in over sixty works. The last works to use the bass in A are, I believe, Strauss’ Sonatine für Blaser, 1942, and Messiaen’s Turangalîla-Symphonie (1948, revised 1990) and Gunther Schuller’s Duo Sonata (1949) for clarinet and bass clarinet. The instrument has all but disappeared from orchestral use and there are very few left in the world. It is now often called obsolete, despite the historically-informed performance movement over the last half century which emphasizes, inter alia, performance on the instruments originally specified by the composer. And the instrument has been largely neglected by scholars. Leeson1 drew attention to the one-time popularity and current neglect of the instrument, in an article that inspired the current study, and Joppig2 has disussed the use of the various tonalities of clarinet, including the bass in A, by Gustav Mahler. He pointed out that the use of both A and Bb clarinets in both soprano and bass registers was absolutely normal in Mahler’s time, citing Heinrich Schenker writing as Artur Niloff in 19083. Otherwise it has been as neglected in the literature as it is in the orchestra. -

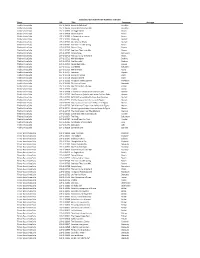

Copy of 2017 Solo & Ensemble Additions

2016/2017 Solo & Ensemble Additions and Edits Event UIL Title Composer Arranger Treble Voice Solo 107-1-32691 Sweet Suffolk Owl Hundley Treble Voice Solo 107-1-32693 Come Ready and See Me Hundley Treble Voice Solo 107-1-32696 Ich Sagte Nicht Beach Treble Voice Solo 107-1-32698 Deine Blumen Beach Treble Voice Solo 107-1-32700 Je Demande a l'oiseau Beach Treble Voice Solo 107-1-32701 Warnung Mozart Treble Voice Solo 107-1-32702 Als Luisa die Briefe Mozart Treble Voice Solo 107-1-32704 The Year's at the Spring Beach Treble Voice Solo 107-1-32705 Pippa's Song Rorem Treble Voice Solo 107-1-32707 See How They LoVe Me Rorem Treble Voice Solo 107-1-32709 Simple Song Bernstein Treble Voice Solo 107-1-32711 The Lord is my Shepherd Childs Treble Voice Solo 107-1-32712 Wir Wandelten Brahms Treble Voice Solo 107-1-32713 Die Mainacht Brahms Treble Voice Solo 107-1-32714 Susses Begrabnis Loewe Treble Voice Solo 107-1-32715 Standchen Schubert Treble Voice Solo 107-1-32716 Notre Amour Faure Treble Voice Solo 107-1-32717 Lamento Duparc Treble Voice Solo 107-1-32718 OuVre ton Coeur Bizet Treble Voice Solo 107-1-32719 Chanson d'AVril Bizet Treble Voice Solo 107-1-32721 Ho Sparse Tante Lagrime Morlacchi Treble Voice Solo 107-1-32723 Oh, Vieni al Mare Donizetti Treble Voice Solo 107-1-32725 Non t'accostare all'urnA Ferrari Treble Voice Solo 107-1-32727 L'addio Vaccai Treble Voice Solo 107-1-32728 In Uomini in soldati from Cosi fan tutte Mozart Treble Voice Solo 107-1-32729 Una Donna a Quindici anni from Cosi fan Tutte Mozart Treble Voice Solo 107-1-32730 Batti -

Chalumeau in Oxford Music Online Oxford Music Online

18.3.2011 Chalumeau in Oxford Music Online Oxford Music Online Grove Music Online Chalumeau article url: http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com:80/subscriber/article/grove/music/05376 Chalumeau (from Gk. kalamos , Lat. calamus : ‘reed’). A single-reed instrument of predominantly cylindrical bore, related to the clarinet (it is classified as an AEROPHONE ). The term originally denoted a pipe or bagpipe chanter, but from the end of the 17th century was used specifically to signify the instrument discussed below. 1. History and structure. It seems likely that the chalumeau evolved in the late 17th century from attempts to increase the volume of sound produced by the recorder; the retention of the latter’s characteristic foot-joint is evidence of the close physical relationship between the two instruments. Two diametrically opposed keys were soon added above the seven finger-holes and thumb-hole of the chalumeau, bridging the gap between the highest note and the lowest overblown 12th. The relatively large dimensions of the vibrating reed and the mouthpiece to which it was tied, however, were principally designed to produce the fundamental register. The clarinet itself evolved when the thumb-hole was repositioned, the mouthpiece was reduced in size to facilitate overblowing, and the foot-joint was replaced by a bell to improve the projection of sound. Since the clarinet functioned rather unsatisfactorily in its lowest register, the chalumeau was able for a time to retain its separate identity. J.F.B.C. Majer remarked that since the technique required was broadly comparable, a recorder player could handle the chalumeau, though the latter is described as ‘very hard to blow because of its difficult mouthpiece’ (‘ratione des schweren Ansatzes sehr hart zu blasen’).