Counting the Omer–A Subject of Dispute

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bread and Counting the Omer

MAY 2016 Bread and Counting the Omer In the Book of Deuteronomy, we read: [God] subjected you to the hardship of hunger and then gave you manna to eat. in order to teach you that man does not live on bread alone. (Deuteronomy 8:3). This passage draws a connection between the consumption of bread and the human spirit, as it seeks to remind us that there is more to eating than the mere cessation of hunger. Most of us can fully relate to this concept, and we articulate it on a regular basis when we say, “Oh my God! This is delicious.” Others, like me, could actually “live on bread alone” and be very content. All kidding aside, food and faith go hand in hand in Judaism, and bread in particular plays a very central role (pun intended). Bread not only fills the belly, it also enriches the human spirit. Every culture has bread. Every faith includes bread in ritual practices. In Judaism, bread holds a sacred place in every single meal we eat. Traditionally, there is a special blessing (the Motzi) that is recited ONLY when bread is going to be consumed. For any meal or snack that does not include bread, shorter blessings are recited before and after the meal. Bread is also associated with the study of Torah. Our sages saw each as being part of a daily diet for the body and mind when they taught, “Im ain kemach ain Torah – Without flour (dough) there is no Torah.” In other words, physical and spiritual nourishment are inextricably linked. -

Chol Hamoed Packet.Pdf

Table of Contents Introduction of Hilchos Chol HaMoed ....................................................................................... 2 Excursions and Trips on Chol HaMoed (Josh Blau) ................................................................. 3 Writing on Chol HaMoed............................................................................................................. 4 Haircuts and Shaving on Chol HaMoed (Dubbin Hanon)........................................................ 5 Cutting One’s Nails on Chol HaMoed (Ari Zucker).................................................................. 6 Photograpy on Chol HaMoed (Josh Blau).................................................................................. 7 Laundry on Chol HaMoed ........................................................................................................... 8 Physical Needs on Chol HaMoed................................................................................................. 8 Hired Workers on Chol HaMoed (Jonah Sieger) ...................................................................... 9 Shopping on Chol HaMoed (Shmuel Garber).......................................................................... 10 Issur Melacha on Erev Pesach (Robby Schrier) ...................................................................... 11 Preface With Hakadosh Baruch Hu’s kindness we succeeded in compiling an interesting and extensive collection of articles on the halachos of Chol Hamoed. In an effort to spread Torah and understand the complex -

Rabbi Ovadia Yosef: Sectorial Party Leader Or a Social Revolutionary? - National Israel News | Haaretz

10/8/13 Rabbi Ovadia Yosef: Sectorial party leader or a social revolutionary? - National Israel News | Haaretz SUBSCRIBE TO HAARETZ DIGITAL EDITIONS TheMarker Café ISRAEL MINT עכבר העיר TheMarker הארץ Haaretz.com Jewish World News Hello Desire Pr ofile Log ou t Do you think I'm You hav e v iewed 1 of 10 articles. subscri be now sexy? Esquire does Search Haaretz.com Tuesday, October 08, 2013 Cheshvan 4, 5774 NEWS OPINION JEWISH WORLD BUSINESS TRAVEL CULTURE WEEKEND BLOGS ARCHAEOLOGY NEWS BROADCAST ISRAEL NEWS Rabbi Ovadia Y osef World Bank report Israel's brain drain Word of the Day Syria Like 83k Follow BREAKING NEWS 1:3219 PM Anbnoouut n10c eSmyerinatn osf t Nryo tboe cl rpohsyss oicvse pr rbizoer dlaeur rfeantcee d ienltaoy Iesdr,a nelo ( Hdeataarielstz g)iven (AP) More Breaking News Home New s National Analysis || Rabbi Ovadia Yosef: Sectorial party leader or HAARETZ SELECT a social revolutionary? To see the greatness of Rabbi Ovadia Yosef, one must look separately at Ovadia A and Ovadia B. By Yair Ettinger | Oct. 8, 2013 | 9:03 AM | 1 7 people recommend this. Be the first of your 1 Tw eet 3 Recommend Send friends. The Israel Air Force flyover at Auschwitz: A crass, superficial display Why the Americans could not hav e bombed the death camp until July 1 944, and why the 2003 fly ov er there was a mistake. A response to Ari Shav it. By Yehuda Bauer | Magazine On Twitter, nothing is sacred - not even Rabbi Ovadia Yosef By Allison Kaplan Sommer | Routine Emergencies Ary eh Deri, (L), a political kingmaker and head of Shas, holding the hand of the party 's spiritual leader, Rabbi Ov adia Yosef in 1 999. -

Unit: Our Relationship to the Land: Meaning of the Omer Lesson

Unit: Our Relationship to the Land: Meaning of the Omer Lesson One: Everything Comes From The Land Let’s begin this Study: As we consider the period of Sefirat HaOmer/ Counting the Omer, we will examine the connection between the Jewish holidays at both יציאת מצרים /the time of our leaving of Egypt , פסח /ends of this period. Peasch begins this “counting of the barley” which continues for seven weeks and Shavuot/ completes this קבלת התורה /the observance of our receiving of the Torah , שבועות period of time. In thinking of these celebrations in this manner, we talk about their historical meanings. Additionally, we must also be mindful of the agricultural and land-linked meanings of these holidays and the time in which they come. The lessons embedded in their very being and the cycle of which they are a part are as critical to us as G-d’s protection and instruction through Torah, of which this cycle is a part, actually leading up to our celebration of this defining aspect of our identity. To begin this lesson, your teacher will ask you: What is the Counting of the Omer/ Sefirat HaOmer and what does it mean to us as Jews? What exactly is it that we are counting during this period of time? What lessons can we learn about the land and its meaning in our lives from this season and its heightened consciousness about our land and its resources? Write your thoughts here: __________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________ -

Biblical and Talmudic Units of Measurement

Biblical and Talmudic units of Measurement [email protected] – י"ז אב תשע"ב Ronnie Figdor 2012 © Sources: The size of Talmudic units is a matter of controversy between: [A] R’ Chaim Naeh. Shi’urei Torah. 1947, [B] the Hazon Ish (Rabbi Avraham Ye- shayahu Karelitz 1878-1953) Moed 39: Kuntres Hashiurim and [C] R’ Moshe Feinstein (Iggerot Moshe OC I:136,YD I:107,YD I:190,YD III:46:2,YD III:66:1). See also Adin Steinsaltz. The Talmud, the Steinsaltz edition: a Reference Guide. Israel V. Berman, translator & editor NY: Random House, 1989, pp.279-293. Volume Chomer1 (dry)=kor (dry,liquid). Adriv=2letech (dry). Ephah3 (dry)=4Bat5 (liquid). Se’ah (dry)6. Arbaim Se’ah (40 se’ah), the min. quantity of kor7 8 9 10 1 11 12 water necessary for a mikveh (ritual bath), is the vol. of 1x1x3 amot . Tarkav =hin (liquid). Liquid measures include a hin, ½ hin, ∕3 hin, ¼ hin, letech 2 1 1 1 13 14 15 a log (also a dry measure), ½ log, ¼ log, ∕8 log & an ∕8 of an ∕8 log which is a kortov (liquid). Issaron (dry measure of flour)=Omer ephah 5 10 (dry) measure of grain16. Kav (dry,liquid) is the basic unit from which others are derived. Kabayim17 (dry)=2 kav. Kepiza18 (dry) se’ah 319 1512 30 1 20 21 1 22 is the min. measure required for taking Challah. Kikar (loaf)= ∕3 kav. P’ras (½ loaf ) or Perusah (broken loaf)= ∕6 kav tarkav 2 6 30 60 23 1 24 20 25 26 52 2 1 27 = 4 betzim. -

Tz7-Sample-Corona II.Indd

the lax family special edition Halachic Perspectives on the Coronavirus II נקודת מבט על נגיף הקורונה ב׳ Tzurba M’Rabanan First English Edition, 2020 Volume 7 Excerpt – Coronavirus II Mizrachi Press 54 King George Street, PO Box 7720, Jerusalem 9107602, Israel www.mizrachi.org © 2020 All rights reserved Written and compiled by Rav Benzion Algazi Translation by Rav Eli Ozarowski, Rav Yonatan Kohn and Rav Doron Podlashuk (Director, Manhigut Toranit) Essays by the Selwyn and Ros Smith & Family – Manhigut Toranit participants and graduates: Rav Otniel Fendel, Rav Jonathan Gilbert, Rav Avichai Goodman, Rav Joel Kenigsberg, Rav Sam Millunchick, Rav Doron Podlashuk, Rav Bentzion Shor General Editor and Author of ‘Additions of the English Editors’: Rav Eli Ozarowski Board of Trustees, Tzurba M’Rabanan English Series: Jeff Kupferberg (Chairman), Rav Benzion Algazi, Rav Doron Perez, Rav Doron Podlashuk, Ilan Chasen, Adam Goodvach, Darren Platzky Creative Director: Jonny Lipczer Design and Typesetting: Daniel Safran With thanks to Sefaria for some of the English translations, including those from the William Davidson digital edition of the Koren Noé Talmud, with commentary by Rabbi Adin Even-Israel Steinsaltz www.tzurba.com www.tzurbaolami.com Halachic Perspectives on the Coronavirus II נקודת מבט על נגיף הקורונה ב׳ Introduction “Porch” and Outdoor Minyanim During Coronavirus Restrictions Responding to a Minyan Seen or Heard Online Making a Minyan Using Online Platforms Differences in the Tefilla When Davening Alone Other Halachot Related to Tefilla At Home dedicated in loving memory of our dear sons and brothers יונתן טוביה ז״ל Jonathan Theodore Lax z”l איתן אליעזר ז״ל Ethan James Lax z”l תנצב״ה marsha and michael lax amanda and akiva blumenthal rebecca and rami laifer 5 · נקודות מבט הלכתיות על נגיף הקורונה ב׳ צורבא מרבנן Introduction In the first shiur concerning the coronavirus, we discussed some of the halachic sources relating to the proper responses, both physical and spiritual, to an epidemic or pandemic. -

Emor, the Omer, and Shavuot

Emor, the Omer, and Shavuot When you enter the land that I am giving you and you reap its harvest, you shall bring the first sheaf of your harvest to the priest. He shall elevate the sheaf before Adonai for acceptance on your behalf…And from the day on which you bring the sheaf of elevation offering—the day after the Sabbath—you shall count off seven weeks. They must be complete: you must count until the day after the 7th week—fifty days; then you shall bring an offering of new grain to Adonai. (Leviticus 23:10-16) From the Midrash Thus is it written: [Vanity of vanities, said Kohelet; all is vanity/futility/emptiness!] What profit/benefit is there for a person in all his labor that he labors under the sun? (Kohelet 1:2-3) Rabbi Samuel bar Nachmani said: They sought to hide away the book of Kohelet, for they found in it things that inclined towards heresy. They said: Should Solomon have said the following: What benefit is there for a person in all his labor—is it possible that even in the labor of Torah was included?? But they said: If Solomon had said, “in all labor” and left it at that, we might have said that even the labor of [studying] Torah is included, but he does not say this, rather, “in all his labor”—that is, in his own labor there is no profit [it accomplishes nothing], but in the labor of Torah there is profit [accomplishment]. Said Rabbi Yudan: “Under the sun” he has none, but above the sun he does. -

A Missed Day in the Life of the Omer

A Missed Day in the Life of the Omer O.H. 489:8.2009 Rabbi Bradley Shavit Artson & Rabbi Aaron Alexander This responsum was approved by the CJLS on October 14, 2009 by a vote of eleven in favor (11-3-4). Members voting in favor: Rabbis Kassel Abelson, Miriam Berkowitz, Elliot Dorff, Robert Fine, Baruch Frydman-Kohl, Reuven Hammer, Josh Heller, Daniel Nevins, Elie Spitz, Loel Weiss, David Wise. Members voting against: Rabbis Pamela Barmash, Paul Plotkin, and Adam Kligfeld. Members Abstaining: Rabbis Eliezer Diamond, Susan Grossman, Jane Kanarek, and Jay Stein. The Committee on Jewish Law and Standards of the Rabbinical Assembly provides guidance in matters of Halakhah for the Conservative movement. The individual rabbi, however, is the authority for the interpretation and application of all matters of halakhah. : What may a person who completely forgets a 24-hour cycle of counting the Omer do vis-a-vis counting on subsequent days? May one continue counting the Omer? May one continue to count with a blessing? May one count but without a blessing?1 : – : : From the day on which you bring the sheaf of elevation offering—the day after the Sabbath—you shall count off seven weeks. They must be complete (temimot): you must count until the day after the seventh week—fifty days; then you shall bring an offering of new grain to the Lord. (Lev. 23:15-16) In the era of the , the Omer existed as an offering of the first of the new barley har- vest, beginning on the sixteenth of Nissan, the second day of Pesah according to Talmudic hermeneutics.2 Even after the destruction of the Temple, the obligation to 'count the days' re- 1. -

Counting of the Omer.Pdf

Counting of the Omer at the Beth Sholom Library April/May 2009 FOR ADULTS: Domnitch, Larry. The Jewish Holidays: A Journey Through History. (Jason Aronson, 2000; ISBN: 0-7657- 6109-2). See pp. 45-53. Haber, Rabbi Yaacov with Rabbi David Sedley. Sefiros: Spiritual Refinement Through Counting the Omer. (Judaica Press, 2008; ISBN: 978-1-60763-010-4). “Sefiros takes you on a seven-week journey of spiritual refinement and improvement, providing you with practical techniques to maximize the growth potential inherent in each of the forty-nine days of Sefirah.” Jacobson, Rabbi Simon. A Spiritual Guide to the Counting of the Omer: Forty-nine Steps to Personal Refinement According to the Jewish Tradition. (Vaad Hanochos Hatmimim, 1996; ISBN: 1-886587-23-X). “Each day of sefirah has in it a specific area for growth and exercises for positive change. We invite you to use this book as a workbook, reading it, following the exercises, creating exercises that are relevant for you, and recording in it positive changes you’ve made in your life. Kitov, Eliyahu. The Book of Our Heritage. (Feldheim, 1978; ISBN: 0-87306-154-3). See pp. 15-45 (Iyar). Miron, Issachar. Eighteen Gates of Jewish Holidays and Festivals. (Jason Aronson, 2000; ISBN: 0-87668- 563-7). See pp. 164-171. Steinberg, Paul. Celebrating the Jewish Year: The Spring and Summer Holidays. (JPS, 2009; ISBN: 978-0- 8276-0850-4). See pp. 91-134. Strassfeld, Michael. The Jewish Holidays: A Guide and Commentary. (Harper & Row, 1985; ISBN: 0-06- 015406-3). See pp. 47-67. Syme, Daniel B. -

Introduction to the Omer with Rabbi Jonathan Slater

Omer 5781: Introduction to the Omer with Rabbi Jonathan Slater The period of the “Counting of the Omer” extends from the eve of the second day of Passover, up to the holiday of Shavuot, the “Feast of Weeks”. In total, there are fifty days, but the intermediate days – between the first day of Passover and Shavuot – are forty-nine (see Deut. 16:9-12 and Lev. 23:15-18). The number forty-nine is significant, as indicated in these biblical passages, as it is the square of seven; it is made up of seven days of the week over seven weeks. The Torah links Passover and Shavuot, as well as the time between them, to the seasons of the year and their implication for crops growing then. The Sages, much later, linked the Exodus from Egypt to the Giving of Torah to the beginning and end of this period of time. Especially in our diaspora, when many (most) Jews no longer were farmers, the agricultural significance diminished before the “historical”. In the mind of the Sages, the night of the Passover – the eve of the Exodus – was one of miracles and wonders. It was the night of the Tenth Plague, a night of watching, of anticipation, of danger, and of hope. That plague, in contrast with all the others, was brought about through God’s direct action: “For that night I will go through the land of Egypt and strike down every first-born in the land of Egypt, both man and beast; and I will mete out punishments to all the gods of Egypt, I YHVH” (Ex. -

Degruyter Opphil Opphil-2020-0140 664..680 ++

Open Philosophy 2020; 3: 664–680 Changing One’s Mind: Philosophy, Religion and Science Omer Michaelis* Crisis discourse and framework transition in Maimonides’ Mishneh Torah https://doi.org/10.1515/opphil-2020-0140 received September 10, 2020; accepted September 23, 2020 Abstract: In his works from the past decade, Menachem Fisch offered an analysis of a crucial distinction between two modes of rationalized transformation: an intra-framework transformation and an inter-framework one, the latter entailing a revolutionary shift of the framework itself. In this article, I analyze the attempt to produce such a framework transition in the tradition of Jewish Halakha (i.e., Jewish Law) by one of the key figures in its history, Moses Maimonides (1135–1204), and to explore how this transition was rationalized and promoted by the utilization of crisis discourse. Using discourse analysis, I analyze the introduction to Maimonides’ great legal code, Mishneh Torah, and explore the modes by which he sought to establish, install and stabilize a homogenous and centralistic legal order at the center of which will lie one – that is, his own – Halakhic book. Keywords: Maimonides, Jewish Halakha, framework transition, Mishneh Torah, Medieval Judaism, crisis discourse, Menachem Fisch 1 Introduction In his works from the past decade, Menachem Fisch offered an analysis of a crucial distinction between two modes of rationalized transformation: an intra-framework transformation and an inter-framework one, the latter entailing a revolutionary shift of the framework itself. The specific philosophical problematics of the inter-framework transformation have been explored in both Fisch’s collaborative study with Itzhak Benbaji, The View from Within (2013) and in his independent study, Creatively Undecided (2017).¹ The point of departure for both works is the critical enterprise of Immanuel Kant, and in particular the Kantian realiza- tion in the First Critique with regard to judgments that are constituted by a set of a priori principles, i.e., framework dependent. -

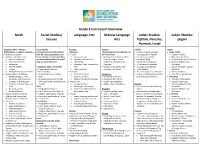

Grade 3 Curriculum Overview Math Social Studies/ Science Language

Grade 3 Curriculum Overview Math Social Studies/ Language Arts Hebrew Language Judaic Studies: Judaic Studies: Science Arts Tefillah, Parasha, Hagim Humash, Israel Singapore Math - Primary Social Studies Reading Reading Tefillah Hagim Mathematics - is used in Grades K-5 Communities Around the World Literature *Using Haverim B’Ivrit and the Tal ● Creating a Makom Kadosh ● Hagei Tishrei ● Numbers to 10,000 How do culture, geography, and ● Fiction Am Curriculum ● Choreography of Tefillah ○ Hodesh Ha’Slihot ● Addition and Subtraction history shape a community? How ○ Character Study ● Reading Short Fiction and Non- ● Introduction to Hallel ○ Mitzvah of the Shofar ○ Mental Calculation are world communities the same? ○ Conflict and Resolution Fiction Passages, Letters, ● Mashiv Ha’Ruah ○ Cycles and the Lunar Calendar ○ Sum and Difference How are they different? ○ Inferencing Invitations, and Comics for ● Modim at Thanksgiving ○ Brachot, Mitzvot, and ○ Estimation ○ Character Traits - Beyond the Meaning ● Al Ha’Nisim at Hanukkah Minhagim ○ Word Problems Geography, Maps, and Globes Text ● Reading in All Genres with ● Introduction to Minhah ○ Sukkah K’Sherah - Layshev ○ 4-digits ● Geographical Features ○ Setting and Plot Accuracy and Fluency ● Hatzi Kaddish BaSukkah ○ Multiple-Step Word Problems ● Kinds of Maps ● Folktales ● Avot and Imahot in the Amidah ○ Arba’at HaMinim ● Multiplication and Division ● Structural Features of Maps ○ Traits of the Genre Vocabulary ● Shalom in Tefillah (Oseh Shalom, ○ Yom Tov vs. Hol Hamoed ○ Multiplying Ones, Tens,