Brian Friel, Ireland and Globalisation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Page 1 of 562 JEK James and Elizabeth Knowlson Collection This Catalogue Is Based on the Listing of the Collection by James

University Museums and Special Collections Service JEK James and Elizabeth Knowlson Collection This catalogue is based on the listing of the collection by James and Elizabeth Knowlson 1906-2010 JEK A Research material created by James and Elizabeth Knowlson JEK A/1 Material relating to Samuel Beckett JEK A/1/1 Beckett family material JEK A/1/1/1 Folder of Birth Certificates, Parish registers and Army records Consists of a copy of the Beckett Family tree from Horner Beckett, a rubbing of the plaque on William Beckett’s Swimming Cup, birth certificates of the Roes and the Becketts, including Samuel Beckett, his brother, mother and father and photograph of the Paris Register Tullow Parish Church and research information gathered by Suzanne Pegley Page 1 of 562 University Museums and Special Collections Service James Knowlson note: Detailed information from Suzanne Pegley who researched for James and Elizabeth Knowlson the families of both the Roes – Beckett’s mother was a Roe - and the Becketts in the records of the Church Body Library, St Peter’s Parish, City of Dublin, St Mary’s Church Leixlip, the Memorial Registry of Deeds, etc. Very detailed results. 2 folders 1800s-1990s JEK A/1/1/2 Folder entitled May Beckett’s appointment as a nurse Consists of correspondence James Knowlson note: Inconclusive actually 1 folder 1990s JEK A/1/1/3 Folder entitled Edward Beckett Consists of correspondence James Knowlson note: Beckett’s nephew with much interesting information. 1 folder 1990s-2000s JEK A/1/1/4 Folder entitled Caroline Beckett Murphy Consists -

Read the Performance Program Here!

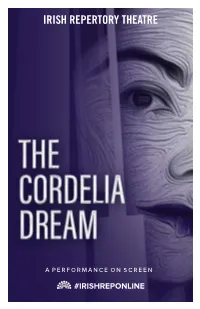

IRISH REPERTORY THEATRE A PERFORMANCE ON SCREEN IRISH REPERTORY THEATRE CHARLOTTE MOORE, ARTISTIC DIRECTOR | CIARÁN O’REILLY, PRODUCING DIRECTOR A PERFORMANCE ON SCREEN Irish Repertory Theatre Presents In association with Bonnie Timmermann THE CORDELIA DREAM BY MARINA CARR DIRECTED BY JOE O'BYRNE STARRING STEPHEN BRENNAN AND DANIELLE RYAN cinematography & editor set design costume design sound design & original music NICK ROBERT JESSICA DAVID RYAN BALLAGH CASHIN DOWNES production manager stage manager press representatives general manager LEO AIDAN MATT ROSS LISA MCKENNA DOHENY PUBLIC RELATIONS FANE TIME & PLACE The Present - Dublin, Ireland Running Time: 90 minutes, no intermission SPECIAL THANKS Anthony Fox, Eva Walsh, Rhona Gouldson, Archie Chen, and a very special thanks to the Howard Gilman Foundation for their support of our digital initiatives. The Cordelia Dream was first presented by the Royal Shakespeare Company at Wilton’s Music Hall on December 11, 2008. THIS PRODUCTION IS MADE POSSIBLE WITH PUBLIC FUNDS FROM THE NEW YORK STATE COUNCIL ON THE ARTS, THE NEW YORK CITY DEPARTMENT OF CULTURAL AFFAIRS, AND OTHER PRIVATE FOUNDATIONS AND CORPORATIONS, AND WITH THE ASSISTANCE OF THE MANY GENEROUS MEMBERS OF IRISH REPERTORY THEATRE’S PATRON’S CIRCLE. WHO’S WHO IN THE CAST STEPHEN BRENNAN the Paycock (Guthrie Theatre, (Man) Stephen was a Minneapolis), Sorin in The Seagull member of the Abbey (Dublin Festival), John Bosco in The Theatre company from Chastitute (Gaiety, Dublin), The Captain 1975, playing a wide in Woyzeck in Winter (Galway Festival/ variety of roles including Barbican) and Hornby in A Kind of Joe Dowling's production Alaska (Pinter Festival, Lincoln Centre). -

IRISH FILM and TELEVISION ‐ 2009 the Year in Review Tony Tracy (Ed.)

Estudios Irlandeses, Number 5, 2010, pp. 203-255 ____________________________________________________________________________________________ AEDEI IRISH FILM AND TELEVISION ‐ 2009 The Year in Review Tony Tracy (ed.) Irish Film and Television Review 2009. Introduction Tony Tracy ..............................................................................................................................204 Myth and Murder in The Daisy Chain Zélie Asava ..............................................................................................................................209 Troubles Cinema: Five Minutes of Heaven & Fifty Dead Men Walking Ruth Barton .............................................................................................................................213 “Looking at the Stars”: TV3 adapts Lady Windermere’s Fan Liam Burke.............................................................................................................................216 Masks and Faces: Identities Dennis Condon .....................................................................................................................220 Being Digital – Irish cinema and digital production Roddy Flynn ............................................................................................................................223 The Yellow Bittern Robert Furze ............................................................................................................................228 Donal Donnelly: An Appreciation Michael Patrick Gillespie -

Exploring the Past in Irish Film

Provided by the author(s) and NUI Galway in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite the published version when available. Title Irish intolerance: exploring its roots in Irish cinema Author(s) Crosson, Seán Publication Date 2011 Crosson, S. (2011) ' Irish Intolerance: Exploring its Roots in Publication Irish Cinema ' In: Huber, Werner; Crosson, S(Eds.). Information Contemporary Irish Film: New Perspectives on a National Cinema. Vienna : Braumüller. Publisher Braumüller Link to publisher's http://www.braumueller.at version Item record http://hdl.handle.net/10379/6787 Downloaded 2021-09-26T18:49:52Z Some rights reserved. For more information, please see the item record link above. 1 Irish Intolerance: Exploring Its Roots in Irish Cinema Seán Crosson [Published in Contemporary Irish Film (Braumüller, 2011), pp. 23-36.] I very strongly believe that a lot of what has been going on in this country for the last year, to me it’s an offence to common decency actually. I think that it’s an offence to ourselves and to our own self respect as people ... the kind of unpleasant and insinuating remarks that people, the kind of deep suspicion, and it is not what I know Irish people to be and yet we suddenly find ourselves confronted with this awful thing and finding a part of us exposed ... (Gerry Stembridge) These comments were made by Irish film director Gerry Stembridge during an interview concerning his TV drama A Black Day at Black Rock (2001) on the popular RTE talk show The Late Late Show in January 2001. A Black Day at Black Rock is set in the fictional Irish village of Black Rock, many of whose residents react with fear and “deep suspicion” when they are informed that thirty asylum seekers are to be housed in a hostel in their community. -

The Irish Play on the New York Stage, 1874-1966

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Literature in English, Ireland English Language and Literature 1997 The Irish Play on the New York Stage, 1874-1966 John P. Harrington Cooper Union Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Harrington, John P., "The Irish Play on the New York Stage, 1874-1966" (1997). Literature in English, Ireland. 3. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_english_language_and_literature_ireland/3 IRISH LITERATURE, HISTORY, AND CULTURE This page intentionally left blank THE IRISH PLAY ON THE NEW YORK STAGE 1874-1966 John l? Harrington THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY Publication of this volume was made possible in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Copyright © 1997 by The University Press of Kentucky Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine College, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Club Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. All rights reserved Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky 663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008 01 00 99 98 97 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Harrington, John ~ The Irish play on the New York stage, 1874-1966/ John ~ Harrington p. -

Dan O'herlihy Papers P202

Dan O’Herlihy Papers P202 UCD Archives School of History and Archives archives @ucd.ie www.ucd.ie/archives T + 353 1 716 7555 F + 353 1 716 1146 © 2006 University College Dublin. All rights reserved ii Dan O’Herlihy Papers Dan O’Herlihy: Biographical history iv Filmography viii Dan O’Herlihy Papers: content and structure A Professional Career I Hollywood—Early Years, 1945–55 1 II Photographs, c 1945–c 2000 2 III Agents and Contracts, 1946–[2005] 3 IV Filmography and Interviews, 1947–2002 5 V Nomination and Awards, 1954–99 6 VI Script and Screenplay Options and 8 Corrig Avenue—A Film Company, 1956–97 VII Correspondence, 1967–2002 14 VIII Equity, Union and Professional Membership, 15 1981–2002 IX Dissociated Material, [1940]; 1996–98 16 B Performance Career I Theatre, 1941–96 18 II Film, 1947–93 26 III Television, 1954–99 37 C Personal I Drawings and Sketches 45 II Biographical, 1917–2005 47 III Correspondence, 1948–2002 50 © UCD Archives 2006 iii Dan O’Herlihy Papers Biographical history Dan O’Herlihy was born on 1st May 1919 in Wexford to John O’Herlihy, a civil servant and Ellen née Hanton. When Dan was a year old he moved with his family to Dublin, attended CBS in Dún Laoghaire and went on to study architecture in University College Dublin. During his time as a student in UCD Dan took part in the Irish Drama Festival and was awarded a gold medal for his performance. This in turn led to him being offered work in the Abbey Theatre, performing in over 60 productions by the time he graduated in 1945. -

War Cinema– Or How British Films Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Affluent Society

1 THE PROFESSIONAL OFFICER CLASS IN POST- WAR CINEMA– OR HOW BRITISH FILMS LEARNED TO STOP WORRYING AND LOVE THE AFFLUENT SOCIETY A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Andrew Roberts College of Business, Arts and Social Sciences of Brunel University 22nd September2014 2 ABSTRACT My central argument is that mainstream British cinema of the 1951 – 1965 period marked the end of the paternalism, as exemplified by a professional ‘officer class’, as consumerism gradually came to be perceived as the norm as opposed to a post-war enemy. The starting point is 1951, the year of the Conservative victory in the General Election and a time which most films were still locally funded. The closing point is 1965, by which point the vast majority of British films were funded by the USA and often featured a youthful and proudly affluent hero. Thus, this fourteen year describes how British cinema moved away from the People as Hero guided by middle class professionals in the face of consumerism. Over the course of this work, I will analyse the creation of the archetypes of post-war films and detail how the impact of consumerism and increased Hollywood involvement in the UK film industry affected their personae. However, parallel with this apparently linear process were those films that questioned or attacked the wartime consensus model. As memories of the war receded, and the Rank/ABPC studio model collapsed, there was an increasing sense of deracination across a variety of popular British cinematic genres. From the beginning of our period there is a number films that infer that the “Myth of the Blitz”, as developed in a cinematic sense, was just that and our period ends with films that convey a sense of a fragmenting society. -

Verleihkopien

Mitglied der Fédération D FF – Deutsches Filminstitut & Tel.: +49 (0)611 / 97 000 10 www.dff.film Wiesbadener Volksbank Internationale des Archives Filmmuseum e.V. Fax: +49 (0)611 / 97 000 15 E-Mail: wessolow [email protected] IBAN: D E45510900000000891703 du Film (FIAF) Filmarchiv BIC: WIBADE5W XXX Friedrich-Bergius-Stra ß e 5 65203 Wiesbaden 8 / 2019 Verleihkopien Eine Auswahl aus unserem Archiv-Bestand Wir bieten16mm und 35mm Filmkopien, sowie DVDs und DCPs für den nichtkommerziellen Verleih an. Die angegebenen Preise verstehen sich pro Vorführung (zzgl. 7% MwSt. und Transportkosten). * Preis ohne Vorführrechte; Details erfragen Sie bitte im Filmarchiv Darüber hinaus stehen Ihnen noch weitere Filme zur Verfügung. Auskunft über den technischen Zustand der Kopien erhalten Sie im Filmarchiv. Erläuterung viragiert = ganze Szenen des Films sind monochrom eingefärbt koloriert = einzelne Teile des Bildes sind farblich bearbeitet ohne Angabe = schwarz/weiß restauriert = die Kopie ist technisch bearbeitet rekonstruiert = der Film ist inhaltlich der ursprünglichen Fassung weitgehend angeglichen Kurz-Spielfilm = kürzer als 60 Minuten russ./ eUT = russisch mit englischen Untertiteln dtUT = mit deutschen Untertiteln dt.vorh./engl.vorh. = deutsche oder englische Zwischentitel-Liste vorhanden Einige der Stummfilme sind auch mit Musik vorhanden Zwischen- Stummfilm Titel / Land / Jahr Regie / Darsteller Titel / Format Preis € Tonfilm Sprache Abend der Gaukler Regie: Ingmar Bergman GYKLARNAS AFTON Tonfilm Darsteller: Harriet Andersson Hasse Ekman deutsch -

Monologue Drama in Ireland from 1964 – 2016: Form and Per(Form)Ativity

1 “Impossible Speech” - Monologue Drama in Ireland from 1964 – 2016: Form and Per(form)ativity A thesis submitted to the School of Creative Arts, Trinity College Dublin, in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2018 Tim Barrett, MPhil 2 Declaration I declare that this thesis has not been submitted as an exercise for a degree at this or any other university and it is entirely my own work. I agree to deposit this thesis in the University’s open access institutional repository or allow the library to do so on my behalf, subject to Irish Copyright Legislation and Trinity College Library conditions of use and acknowledgement. ______________________________ Tim Barrett 3 Summary This dissertation is a study of monologue drama by Irish playwrights on the island of Ireland from 1964 to 2016. The starting point of 1964 has been selected as it was the year of the first production of Brian Friel’s Philadelphia Here I Come!, a study of which opens Chapter One of the thesis. The thesis proceeds through a consideration of different productions of monologue plays across recent decades in Irish history and through different social, economic and cultural contexts. I will identify monologue drama as a topic that has received limited attention by scholars and argue that my dissertation addresses that deficit in the field. The critical methodology I have adopted is the analysis of a selection of texts of monologue plays from 1964 to 2016, including references to the first productions of those plays, their critical reception and the historical context in which those plays were produced. -

Papers of Patricia Lynch and R. M. Fox

Leabharlann Náisiúnta na hÉireann National Library of Ireland Collection List No. 79 PAPERS OF PATRICIA LYNCH AND R. M. FOX (MSS 34,923-34,931; 40,248-40,419) (Accession No. 4937) Patricia Lynch (1898-1972) was the author of children’s stories mostly set in Ireland; her husband, R.M. (Richard Michael) Fox (1891-1969), was an historian, journalist, and socialist. Compiled by Margaret Burke Contents Introduction 8 I Papers of Patricia Lynch 10 I.i Literary works 10 I.i.1 Novels 10 I.i.1.A The Green Dragon (1925) 10 I.i.1.B The Cobbler’s Apprentice (1930) 10 I.i.1.C The Turf-cutter’s Donkey (1934) 10 I.i.1.D The Turf-cutter’s Donkey Goes Visiting (1935) 11 I.i.1.E The King of the Tinkers (1938) 11 I.i.1.F The Turf-cutter’s Donkey Kicks Up His Heels (1939) 11 I.i.1.G The Grey Goose of Kilnevin (1939) 11 I.i.1.H Fiddler’s Quest (1941) 12 I.i.1.I Long Ears (1943) 12 I.i.1.J Brogeen of the Stepping Stones (1947) 12 I.i.1.K The Mad O’Haras (1948) 12 I.i.1.L The Dark Sailor of Youghal (1951) 13 I.i.1.M The Boy at the Swinging Lantern (1952) 13 I.i.1.N Brogeen Follows the Magic Tune (1952) 14 I.i.1.O Brogeen and the Green Shoes (1953) 14 I.i.1.P Delia Daly of Galloping Green (1953) 14 I.i.1.Q Brogeen and the Bronze Lizard (1954) 14 I.i.1.R Orla of Burren (1954) 14 I.i.1.S Brogeen and the Princess of Sheen (1955) 15 I.i.1.T Tinker Boy (1955) 15 I.i.1.U The Bookshop on the Quay (1956) 15 I.i.1.V Brogeen and the Lost Castle (1956) 16 I.i.1.W Fiona Leaps the Bonfire (1957) 16 I.i.1.X Brogeen and the Black Enchanter (1958) 16 I.i.1.Y The Old Black Sea -

Early Reception of Brian Friel's Philadelphia

Ilha do Desterro: A Journal of English Language, Literatures in English and Cultural Studies E-ISSN: 2175-8026 [email protected] Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina Brasil Harris, Peter James UNIVERSAL OR PROVINCIAL? : EARLY RECEPTION OF BRIAN FRIEL’S PHILADELPHIA, HERE I COME! Ilha do Desterro: A Journal of English Language, Literatures in English and Cultural Studies, núm. 58, enero-junio, 2010, pp. 23-51 Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina Florianópolis, Brasil Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=478348696002 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Universal or Provincial? : Early Reception of... 23 UNIVERSAL OR PROVINCIAL? : EARLY RECEPTION OF BRIAN FRIEL’S PHILADELPHIA, HERE I COME! Peter James Harris Universidade Estadual Paulista, São José do Rio Preto Abstract: This article, part of a larger research work that resulted in a Professorship Thesis, presents a survey and evaluation of the early reception of one of Brian Friel’s first plays: Philadelphia, Here I Come! (1964). The article also explores the question of emigration from Ireland in the 1950s and 1960s, considering British legislation on the matter, and comments on the eventual influence such issue, among other factors, may have had on criticism about the performance of the play at the time. KeywordsKeywords: Irish theatre, Brian Friel, Philadelphia, Here I Come!, emigration, reception, Britain. A significant number of Brian Friel’s plays have been situated in the fictional town of Baile Beag, in the county of Donegal. -

Brian Friel Papers (Additional)

Leabharlann Náisiúnta na hÉireann National Library of Ireland Collection List No. 180 Brian Friel Papers (Additional) (MSS 42,091 – 42,093; 49,209 – 49,350) (Accession No. 6689 & 6941) Papers of the playwright Brian Friel including correspondence and material relating to his plays, theatre and literature. Also includes financial and legal records and material relating to important events in the life of Brian Friel from 1950 – 2010. Compiled by Fergus Brady with assistance from Karen de Lacey, Avice-Claire McGovern and Nora Thornton, September 2011 1 Introduction....................................................................................................................... 6 Custodial History and Access .......................................................................................... 6 Arrangement ..................................................................................................................... 7 Associated Materials in the National Library of Ireland.............................................. 8 List of productions of plays by Brian Friel, 2000 – 2010............................................... 9 I. Plays ........................................................................................................................... 13 I.i. The Enemy Within (1962)........................................................................................ 13 I.i.1. Productions....................................................................................................... 13 I.ii. Philadelphia, Here