The Quraan and Its Message

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pre-Islamic Arabia

Pre-Islamic Arabia The Nomadic Tribes of Arabia The nomadic pastoralist Bedouin tribes inhabited the Arabian Peninsula before the rise of Islam around 700 CE. LEARNING OBJECTIVES Describe the societal structure of tribes in Arabia KEY TAKEAWAYS Key Points Nomadic Bedouin tribes dominated the Arabian Peninsula before the rise of Islam. Family groups called clans formed larger tribal units, which reinforced family cooperation in the difficult living conditions on the Arabian peninsula and protected its members against other tribes. The Bedouin tribes were nomadic pastoralists who relied on their herds of goats, sheep, and camels for meat, milk, cheese, blood, fur/wool, and other sustenance. The pre-Islamic Bedouins also hunted, served as bodyguards, escorted caravans, worked as mercenaries, and traded or raided to gain animals, women, gold, fabric, and other luxury items. Arab tribes begin to appear in the south Syrian deserts and southern Jordan around 200 CE, but spread from the central Arabian Peninsula after the rise of Islam in the 630s CE. Key Terms Nabatean: an ancient Semitic people who inhabited northern Arabia and Southern Levant, ca. 37–100 CE. Bedouin: a predominantly desert-dwelling Arabian ethnic group traditionally divided into tribes or clans. Pre-Islamic Arabia Pre-Islamic Arabia refers to the Arabian Peninsula prior to the rise of Islam in the 630s. Some of the settled communities in the Arabian Peninsula developed into distinctive civilizations. Sources for these civilizations are not extensive, and are limited to archaeological evidence, accounts written outside of Arabia, and Arab oral traditions later recorded by Islamic scholars. Among the most prominent civilizations were Thamud, which arose around 3000 BCE and lasted to about 300 CE, and Dilmun, which arose around the end of the fourth millennium and lasted to about 600 CE. -

Prophet Mohammed's (Pbuh)

1 2 3 4 ﷽ In the name Allah (SWT( the most beneficent Merciful INDEX Serial # Topic Page # 1 Forward 6 2 Names of Holy Qur’an 13 3 What Qur’an says to us 15 4 Purpose of Reading Qur’an in Arabic 16 5 Alphabetical Order of key words in Qura’nic Verses 18 6 Index of Surahs in Qur’an 19 7 Listing of Prophets referred in Qur’an 91 8 Categories of Allah’s Messengers 94 9 A Few Women mentioned in Qur’an 94 10 Daughter of Prophet Mohammed - Fatima 94 11 Mention of Pairs in Qur’an 94 12 Chapters named after Individuals in Qur’an 95 13 Prayers before Sleep 96 14 Arabic signs to be followed while reciting Qur’an 97 15 Significance of Surah Al Hamd 98 16 Short Stories about personalities mentioned in Qur’an 102 17 Prophet Daoud (David) 102 18 Prophet Hud (Hud) 103 19 Prophet Ibrahim (Abraham) 103 20 Prophet Idris (Enoch) 107 21 Prophet Isa (Jesus) 107 22 Prophet Jacob & Joseph (Ya’qub & Yusuf) 108 23 Prophet Khidr 124 24 Prophet Lut (Lot) 125 25 Luqman (Luqman) 125 26 Prophet Musa’s (Moses) Story 126 27 People of the Caves 136 28 Lady Mariam 138 29 Prophet Nuh (Noah) 139 30 Prophet Sho’ayb (Jethro) 141 31 Prophet Saleh (Salih) 143 32 Prophet Sulayman Solomon 143 33 Prophet Yahya 145 34 Yajuj & Majuj 145 5 35 Prophet Yunus (Jonah) 146 36 Prophet Zulqarnain 146 37 Supplications of Prophets in Qur’an 147 38 Those cursed in Qur’an 148 39 Prophet Mohammed’s hadees a Criteria for Paradise 148 Al-Swaidan on Qur’an 149۔Interesting Discoveries of T 40 41 Important Facts about Qur’an 151 42 Important sayings of Qura’n in daily life 151 January Muharram February Safar March Rabi-I April Rabi-II May Jamadi-I June Jamadi-II July Rajab August Sh’aban September Ramazan October Shawwal November Ziqad December Zilhaj 6 ﷽ In the name of Allah, the most Merciful Beneficent Foreword I had not been born in a household where Arabic was spoken, and nor had I ever taken a class which would teach me the language. -

How Anwar Al-Awlaki Became the Face of Western Jihad

As American as Apple Pie: How Anwar al-Awlaki Became the Face of Western Jihad Alexander Meleagrou-Hitchens Foreword by Lord Carlile of Berriew QC A policy report published by the International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation and Political Violence (ICSR) ABOUT ICSR The International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation and Political Violence (ICSR) is a unique partnership in which King’s College London, the University of Pennsylvania, the Interdisciplinary Center Herzliya (Israel), the Regional Center for Conflict Prevention Amman (Jordan) and Georgetown University are equal stakeholders. The aim and mission of ICSR is to bring together knowledge and leadership to counter the growth of radicalisation and political violence. For more information, please visit www.icsr.info. CONTACT DETAILS For questions, queries and additional copies of this report, please contact: ICSR King’s College London 138 –142 Strand London WC2R 1HH United Kingdom T. +44 (0)20 7848 2065 F. +44 (0)20 7848 2748 E. [email protected] Like all other ICSR publications, this report can be downloaded free of charge from the ICSR website at www.icsr.info. © ICSR 2011 AUTHOR’S NOTE This report contains many quotes from audio lectures as well as online forums and emails. All of these have been reproduced in their original syntax, including all spelling and grammatical errors. Contents Foreword 2 Letter of Support from START 3 Glossary of Terms 4 Executive Summary 6 Chapter 1 Introduction 9 Chapter 2 Methodology and Key Concepts 13 Social Movement Theory 13 Framing and -

Stories of the Prophets

Stories of the Prophets Written by Al-Imam ibn Kathir Translated by Muhammad Mustapha Geme’ah, Al-Azhar Stories of the Prophets Al-Imam ibn Kathir Contents 1. Prophet Adam 2. Prophet Idris (Enoch) 3. Prophet Nuh (Noah) 4. Prophet Hud 5. Prophet Salih 6. Prophet Ibrahim (Abraham) 7. Prophet Isma'il (Ishmael) 8. Prophet Ishaq (Isaac) 9. Prophet Yaqub (Jacob) 10. Prophet Lot (Lot) 11. Prophet Shuaib 12. Prophet Yusuf (Joseph) 13. Prophet Ayoub (Job) 14 . Prophet Dhul-Kifl 15. Prophet Yunus (Jonah) 16. Prophet Musa (Moses) & Harun (Aaron) 17. Prophet Hizqeel (Ezekiel) 18. Prophet Elyas (Elisha) 19. Prophet Shammil (Samuel) 20. Prophet Dawud (David) 21. Prophet Sulaiman (Soloman) 22. Prophet Shia (Isaiah) 23. Prophet Aramaya (Jeremiah) 24. Prophet Daniel 25. Prophet Uzair (Ezra) 26. Prophet Zakariyah (Zechariah) 27. Prophet Yahya (John) 28. Prophet Isa (Jesus) 29. Prophet Muhammad Prophet Adam Informing the Angels About Adam Allah the Almighty revealed: "Remember when your Lord said to the angels: 'Verily, I am going to place mankind generations after generations on earth.' They said: 'Will You place therein those who will make mischief therein and shed blood, while we glorify You with praises and thanks (exalted be You above all that they associate with You as partners) and sanctify You.' Allah said: 'I know that which you do not know.' Allah taught Adam all the names of everything, then He showed them to the angels and said: "Tell Me the names of these if you are truthful." They (angels) said: "Glory be to You, we have no knowledge except what You have taught us. -

The Prophets Seth ( Shis ) Habil Kabil © Play & Learn Sabi Enos ( Anush ) Cainan Mahalaeed Jared ( Yarav ) Enoch ( H

ADAM + Eve 1 The Prophets Seth ( Shis ) Habil Kabil © Play & Learn Sabi Enos ( Anush ) www.playandlearn.org Cainan Mahalaeed Jared ( Yarav ) Enoch ( H. Idris ) Methusela Lamech Noah ( H. Nuh ) Shem Ham Yafis Kan’an (did not get on the Ark) Canaan Cush Nimrod 4 Arpachshad Iram Ghasir Samud Khadir Ubayd Masikh Asif Ubayd H.Salih Saleb Eber ( H. Hud )3 Pelag Rem Midian Serag Mubshakar Nahor Mankeel Terah H. Shuaib Abraham ( H. Ibrahim )5 Haran Nahor + HAGAR ( Hajarah ) + Sarah Ishmael ( H. Ishmael ) Nabit Yashjub 2 Ya’rub Lot (H. Lut) Bethul Tayrah Nahur Laban Rafqa + Isaac ( H. Ishaq ) Muqawwam 6 Udd ( Udad ) Lay’ah Rahil + Jacob ( H. Yaqob ) Isu Razih Maws H. Ayyub Adnan Ma’add Nizar Mudar Rabee’ah Inmar Iyad Joseph ( H. Yusuf ) Banyamin Yahuda Ifra’im 8 more 6 Ilyas Aylan Rahma + H. Ayyub Lavi Mudrika Tanijah Qamah Kahas Imran Khozema Hudhayl Moses (H. Musa) Kanana Asad Asadah Hawn Aaron (H. Haroun) Judah Nazar Malik Abd Manah Milkan Alozar Fakhkhakh Maleeh Yukhlad Meetha Eeshia Fahar ( Qoreish ) Yaseen David (H. Dawood) H. Ilyas Solomon (H. Sulayman) Ghalib Muharib Harith Asad Looi Taym H. Zakariya + Elisabeth Hanna + Imran Kaab Amir Saham Awf Mary (Bibi Mariam) H. Yahya (John) Murra Husaya Adiyy Jesus (H. Isa) Zemah Kilab Yaqdah Tym Farih Abdul Uzzah Nafel Sad Khattab Kab Amr UMAR FATIMA [The Second [One of the first Abu Qahafa Uthman Caliph] coverts to Islam] ABU BAKR Ubaydullah [The First Caliph] Talha Abdullah Hafsa [ Married to Muhammad Umm Kulthoom Aisha Asma the Prophet ] [Married the [Married to Umar [Married to [Married to second -

America, the Second ‘Ad: Prophecies About the D Ownfall of the United States 1

America, The Second ‘Ad: Prophecies about the D ownfall of the United States 1 David Cook 1. Introduction Predictions and prophecies about the United States of America appear quite frequently in modern Muslim apocalyp- tic literature.2 This literature forms a developing synthesis of classical traditions, Biblical exegesis— based largely on Protestant evangelical apocalyptic scenarios— and a pervasive anti-Semitic conspiracy theory. These three elements have been fused together to form a very powerful and relevant sce- nario which is capable of explaining events in the modern world to the satisfaction of the reader. The Muslim apocalyp- tist’s material previous to the modern period has stemmed in its entirety from the Prophet Muhammad and those of his generation to whom apocalypses are ascribed. Throughout the 1400 years of Muslim history, the accepted process has been to merely transmit this material from one generation to the next, without adding, deleting, or commenting on its signifi- cance to the generation in which a given author lives. There appears to be no interpretation of the relevance of a given tradition, nor any attempt to work the material into an apocalyptic “history,” in the sense of locating the predicted events among contemporary occurrences. For example, the David Cook, Assistant Professor Department of Religion Rice University, Houston, Texas, USA 150 America, the Second ‘Ad apocalyptic writer Muhammad b. ‘Ali al-Shawkani (d. 1834), who wrote a book on messianic expectations, does not men- tion any of the momentous events of his lifetime, which included the Napoleonic invasion of Egypt, his home. There is not a shred of original material in the whole book, which runs to over 400 pages, and the “author” himself never speaks— rather it is wholly a compilation of earlier sources, and could just as easily have been compiled 1000 years previ- ously. -

Ancient History of Arabian Peninsula and Semitic Arab Tribes

Advances in Social Sciences Research Journal – Vol.7, No.5 Publication Date: May 25, 2020 D OI:10.14738/assrj.75.8252. Shamsuddin, S. M., & Ahmad, S. S. B. (2020). Ancient History of Arabian Peninsula and Semitic Arab Tribes. Advances in Social Sciences Research Journal, 7(5) 270-282. Ancient History of Arabian Peninsula and Semitic Arab Tribes Salahuddin Mohd. Shamsuddin Faculty of Arabic Language, Sultan Sharif Ali Islamic University, Brunei Darussalam Siti Sara Binti Hj. Ahmad Dean: Faculty of Arabic Language, Sultan Sharif Ali Islamic University, Brunei Darussalam ABSTRACT In this article we introduced first the ancient history of Arabian Peninsula, and pre-Islamic era and then we focused a spot light on the people of Arabian Peninsula, highlighting the four waves of migration of Semitic Arabs from the southern to northern Arabian Peninsula, then we mentioned the situation of Northern Arabs and their tribal fanaticism, then we differentiated between Qahtaniyya and Adnaniyya Arab tribes including their three Classes: Destroyed Arab, Original Arab and Arabized Arab. We also explained the tribal system in the pre-Islamic era, indicating the status of four pillars of the tribal system: 1. Integration and alliance among the tribes 2. Tribal Senate or Parliament 3. Tribes and sovereignty over the tribes 4. Members of the tribes and their duties towards their tribal society In the end we described the master of Arab tribe who was the brightest person had a long experience and often had inherited his sovereignty from his fathers to achieve a high status, but it does not mean that he had a broad sovereignty, as his sovereignty was symbolic. -

Prophet Aadam (A) - Part 1

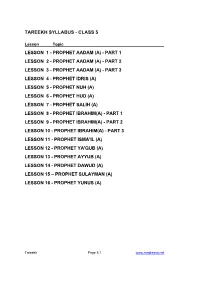

TAREEKH SYLLABUS - CLASS 5 Lesson Topic LESSON 1 - PROPHET AADAM (A) - PART 1 LESSON 2 - PROPHET AADAM (A) - PART 2 LESSON 3 - PROPHET AADAM (A) - PART 3 LESSON 4 - PROPHET IDRIS (A) LESSON 5 - PROPHET NUH (A) LESSON 6 - PROPHET HUD (A) LESSON 7 - PROPHET SALIH (A) LESSON 8 - PROPHET IBRAHIM(A) - PART 1 LESSON 9 - PROPHET IBRAHIM(A) - PART 2 LESSON 10 - PROPHET IBRAHIM(A) - PART 3 LESSON 11 - PROPHET ISMA’IL (A) LESSON 12 - PROPHET YA'QUB (A) LESSON 13 - PROPHET AYYUB (A) LESSON 14 - PROPHET DAWUD (A) LESSON 15 – PROPHET SULAYMAN (A) LESSON 16 - PROPHET YUNUS (A) Tareekh Page 5.1 www.madressa.net PROPHET AADAM PROPHET PROPHET YUNUS IDRIS PROPHET PROPHET SULAYMAN NUH CLASS 5 PROPHET Prophets of PROPHET DAWUD HUD Allah (SWT) PROPHET PROPHET AYYUB SALIH PROPHET PROPHET YA’QUB IBRAHIM PROPHET ISMA’IL Tareekh Page 5.2 www.madressa.net LESSON 1: PROPHET AADAM (A) - PART 1 Prophet Aadam (A) was the first man ever to be created. After Allah had created the earth, the heavens, the sun and the moon, He created angels and the jinn. Finally, He created Prophet Aadam (A) and then Bibi Hawwa (A). When Allah informed the angels that He was going to make a new creation that would live on earth, they were surprised and said, "O Allah, why are you creating new creatures while we are already busy worshipping You and are reciting Your Names all the time? These creatures will fight amongst themselves over the blessings of the earth and kill each other". The angels said this because they had seen the jinn act in this way on the earth. -

The Arabs of North Arabia in Later Pre-Islamic Times

The Arabs of North Arabia in later Pre-Islamic Times: Qedar, Nebaioth, and Others A thesis submitted to The University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2014 Marwan G. Shuaib School of Arts, Languages and Cultures 2 The Contents List of Figures ……………………………………………………………….. 7 Abstract ………………………………………………………………………. 8 Declaration …………………………………………………………………… 9 Copyright Rules ……………………………………………………………… 9 Acknowledgements .….……………………………………………………… 10 General Introduction ……………………………………………………….. 11 Chapter One: Historiography ……………………………………….. 13 1.1 What is the Historian’s Mission? ……………………………………….. 14 1.1.1 History writing ………………………...……....……………….…... 15 1.1.2 Early Egyptian Historiography …………………………………….. 15 1.1.3 Israelite Historiography ……………………………………………. 16 1.1.4 Herodotus and Greek Historiography ……………………………… 17 1.1.5 Classical Medieval Historiography …………………….…………... 18 1.1.6 The Enlightenment and Historiography …………………………… 19 1.1.7 Modern Historiography ……………………………………………. 20 1.1.8 Positivism and Idealism in Nineteenth-Century Historiography…… 21 1.1.9 Problems encountered by the historian in the course of collecting material ……………………………………………………………………… 22 1.1.10 Orientalism and its contribution ………………………………….. 24 1.2 Methodology of study …………………………………………………… 26 1.2.1 The Chronological Framework ……………………………………. 27 1.2.2 Geographical ……………………………………………………….. 27 1.3 Methodological problems in the ancient sources…...………………….. 28 1.3.1 Inscriptions ………………………………………………………… 28 1.3.2 Annals ……………………………………………………………… 30 1.3.3 Biblical sources ...…………………………………………………... 33 a. Inherent ambiguities of the Bible ……………………………… 35 b. Is the Bible history at all? ……………………………………… 35 c. Difficulties in the texts …………………………………………. 36 3 1.4 Nature of the archaeological sources …………………………………... 37 1.4.1 Medieval attitudes to Antiquity ……………………………………. 37 1.4.2 Archaeology during the Renaissance era …………………………... 38 1.4.3 Archaeology and the Enlightenment ………………………………. 39 1.4.4 The nineteenth century and the history of Biblical archaeology……. -

Letter to Shaykh Abu Muhammad 17 August 2007

Page 1 To the kind Shaykh Abu Muhammad, Allah protect him, Peace be upon you, and mercy of Allah, and his blessings. I hope that this message will reach you, and that you, the family, and all the brothers are in health and prosperity from Allah almighty. Please inform me of your condition and the brothers, in-laws, and offspring. I apologize for the delay in sending messages to you, due to security issues seen by the brothers accompanying me and which may last, whereby there will be a message every several months, so please excuse me in that regard, knowing that all of us, praise Allah, are in good condition and health, and hopefully things will ease up and I will be able to meet you and benefit from your opinions. I was following up with the brothers your kind words in supporting people of the right, and confronting people of the evil, which an observer would find as a positive development, Allah reward you and make that in your good deeds balance, due to performing that great duty. Please inform me about the conditions on your side and your future programs, and provide me with your opinions and counsel. - I present to you a very important subject that needs great effort to remove ambiguity around the subject of the Islamic state of Iraq (ISI), since there is easier contact between you, the media, and the information network, so you have to plug that Page 2 gap, whereby the main axis for your work plan in the coming stage would be the continued support for the truthful Mujahidin in Iraq headed by our brothers in ISI, and defending them should be the core issue and should take the lion’s share and the top priority in your speeches and statements, and mobilizing people, and uncovering the opponents’ conspiracies in an open and clear manner, in other words, your support for ISI must be overt and obvious. -

Pre-Islamic Arabia 1 Pre-Islamic Arabia

Pre-Islamic Arabia 1 Pre-Islamic Arabia Pre-Islamic Arabia refers to the Arabic civilization which existed in the Arabian Plate before the rise of Islam in the 630s. The study of Pre-Islamic Arabia is important to Islamic studies as it provides the context for the development of Islam. Studies The scientific studies of Pre-Islamic Arabs starts with the Arabists of the early 19th century when they managed to decipher epigraphic Old South Arabian (10th century BCE), Ancient North Arabian (6th century BCE) and other writings of pre-Islamic Arabia, so it is no longer limited to the written traditions which are not local due to the lack of surviving Arab historians Nabataean trade routes in Pre-Islamic Arabia accounts of that era, so it is compensated by existing material consists primarily of written sources from other traditions (such as Egyptians, Greeks, Romans, etc.) so it was not known in great detail; From the 3rd century CE, Arabian history becomes more tangible with the rise of the Himyarite Kingdom, and with the appearance of the Qahtanites in the Levant and the gradual assimilation of the Nabataeans by the Qahtanites in the early centuries CE, a pattern of expansion exceeded in the explosive Muslim conquests of the 7th century. So sources of history includes archaeological evidence, foreign accounts and oral traditions later recorded by Islamic scholars especially pre-Islamic poems and al-hadith plus a number of ancient Arab documents that survived to the medieval times and portions of them were cited or recorded. Archaeological exploration in the Arabian Peninsula has been sparse but fruitful, many ancient sites were identified by modern excavations. -

Revelation: Catholic and Muslim Perspectives

Prepared by the Midwest Dialogue of Catholics and Muslims Co-Sponsored by the Islamic Society of North America and the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops United States Conference of Catholic Bishops Washington, D.C. Revelation: Catholic and Muslim Perspectives was developed as a resource by the Committee for Ecumenical and Interreligious Affairs of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB) and by the Midwest Dialogue of Catholics and Muslims. It was reviewed by the committee chairman, Bishop Stephen E. Blaire, and has been authorized for publication by the undersigned. Msgr. William P. Fay General Secretary, USCCB Scripture texts used in this work are taken from the New American Bible, copyright © 1991, 1986, and 1970 by the Confraternity of Christian Doctrine, Washington, DC 20017 and are used by permission of the copyright owner. All rights reserved. Excerpts from the Catechism of the Catholic Church, second edition, copyright © 2000, Libreria Editrice Vaticana–United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, Inc., Wash- ington, D.C. Used with permissions. All rights reserved. Excerpts from Vatican II: The Conciliar and Post Conciliar Documents, New Revised Edition, edited by Austin Flannery, OP, copyright © 1996, Costello Publishing Company, Inc., Northport, N.Y., are used with permission of the publisher, all rights reserved. No part of these excerpts may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise—without express written permission of Costello Publishing Company. Excerpts from Bonaventure: The Soul’s Journey into God, The Tree of Life, The Life of St. Francis, translation and introduction by Ewert Cousins; preface by Ignatius Brady, from The Classics of Western Spirituality, copyright © 1978 by Paulist Press, Inc., New York/Mahwah, N.J.