Immortality, Identity, and Desirability Roman Altshuler

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Geology of Cuba: a Brief Cuba: a of the Geology It’S Time—Renew Your GSA Membership and Save 15% and Save Membership GSA Time—Renew Your It’S

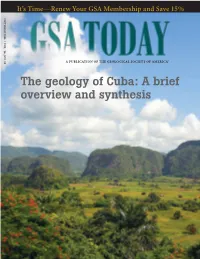

It’s Time—Renew Your GSA Membership and Save 15% OCTOBER | VOL. 26, 2016 10 NO. A PUBLICATION OF THE GEOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF AMERICA® The geology of Cuba: A brief overview and synthesis OCTOBER 2016 | VOLUME 26, NUMBER 10 Featured Article GSA TODAY (ISSN 1052-5173 USPS 0456-530) prints news and information for more than 26,000 GSA member readers and subscribing libraries, with 11 monthly issues (March/ April is a combined issue). GSA TODAY is published by The SCIENCE Geological Society of America® Inc. (GSA) with offices at 3300 Penrose Place, Boulder, Colorado, USA, and a mail- 4 The geology of Cuba: A brief overview ing address of P.O. Box 9140, Boulder, CO 80301-9140, USA. and synthesis GSA provides this and other forums for the presentation of diverse opinions and positions by scientists worldwide, M.A. Iturralde-Vinent, A. García-Casco, regardless of race, citizenship, gender, sexual orientation, Y. Rojas-Agramonte, J.A. Proenza, J.B. Murphy, religion, or political viewpoint. Opinions presented in this publication do not reflect official positions of the Society. and R.J. Stern © 2016 The Geological Society of America Inc. All rights Cover: Valle de Viñales, Pinar del Río Province, western reserved. Copyright not claimed on content prepared Cuba. Karstic relief on passive margin Upper Jurassic and wholly by U.S. government employees within the scope of Cretaceous limestones. The world-famous Cuban tobacco is their employment. Individual scientists are hereby granted permission, without fees or request to GSA, to use a single grown in this valley. Photo by Antonio García Casco, 31 July figure, table, and/or brief paragraph of text in subsequent 2014. -

SMS Unit of Study

SMS Unit of Study Course: Science Teacher(s): Cindy Combs and Sadie Hamm Unit Title: Geologic History of the Earth Unit Length: 8 Days Unit Overview Focus Question: How can rock strata tell the story of Earth’s history? Learning Objective: The student is expected to construct a scientific explanation based on evidence from rock strata for how the geologic time scale is used to organize Earth’s 4.6-billion-year-old history. Standards Set—What standards will I explicitly teach and Summative Assessment—How will I assess my students after explicitly intentionally assess? (Include standard number and complete teaching the standards set? (Describe type of assessment). standard). MS-ESS1.C.1 The History of Planet Earth: The geologic time Ø Presentation of New Species scale interpreted from rock strata provides a way to organize Earth’s history. Analyses of rock strata and the fossil record Ø Presentation of Infomercial or Advertisement provide only relative dates, not an absolute scale. Ø Unit Exam- Multiple Choice, Short Answer, Extended Response MS-ESS1-4 Construct a scientific explanation based on evidence from rock strata for how the geologic time scale is used to organize Earth’s 4.6-billion-year-old history. Time, Space, and Energy Time, space, and energy phenomena can be observed at various scales using models to study systems that are too large or too small. Construct a Scientific Explanation Construct a scientific explanation based on valid and reliable evidence obtained from source (including students' own experiments) and the assumption that theories and laws that describe the natural world operate today as they did in the past and will continue to do so in the future. -

God and Immortality in Dostoevsky's Thought

BYU Studies Quarterly Volume 1 Issue 2 Article 7 4-1-1959 God and Immortality in Dostoevsky's Thought Louis C. Midgley Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq Recommended Citation Midgley, Louis C. (1959) "God and Immortality in Dostoevsky's Thought," BYU Studies Quarterly: Vol. 1 : Iss. 2 , Article 7. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq/vol1/iss2/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in BYU Studies Quarterly by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Midgley: God and Immortality in Dostoevsky's Thought gojgod immortality dostoevsky thought LOUIS C MIDGLEY ivan karamazov dostoevsky nihilist fully recognized consequences denial god immortality ivan gave us two different formulations position first virtue immortality iskBK 66 1 secondly ivan solemnly declared argument nothing whole world make man love neighbours law nature man should love mankind love earth hitherto owing natural law simply men believed immortality you destroy mankind belief immortality love every living force maintaining life world once dried moreover nothing then immoral everything lawful even cannibalism BK 65 final payoffpay off ivan nihilistic doctrine every individual does believe god im- mortality moral law nature must immediately changed exact contrary former religious law egoism even crime must become lawful even recognized inevitable -

Symmetries in Quantum Field Theory and Quantum Gravity

Symmetries in Quantum Field Theory and Quantum Gravity Daniel Harlowa and Hirosi Oogurib;c aCenter for Theoretical Physics Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA 02139, USA bWalter Burke Institute for Theoretical Physics California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA 91125, USA cKavli Institute for the Physics and Mathematics of the Universe (WPI) University of Tokyo, Kashiwa, 277-8583, Japan E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] Abstract: In this paper we use the AdS/CFT correspondence to refine and then es- tablish a set of old conjectures about symmetries in quantum gravity. We first show that any global symmetry, discrete or continuous, in a bulk quantum gravity theory with a CFT dual would lead to an inconsistency in that CFT, and thus that there are no bulk global symmetries in AdS/CFT. We then argue that any \long-range" bulk gauge symmetry leads to a global symmetry in the boundary CFT, whose consistency requires the existence of bulk dynamical objects which transform in all finite-dimensional irre- ducible representations of the bulk gauge group. We mostly assume that all internal symmetry groups are compact, but we also give a general condition on CFTs, which we expect to be true quite broadly, which implies this. We extend all of these results to the case of higher-form symmetries. Finally we extend a recently proposed new motivation for the weak gravity conjecture to more general gauge groups, reproducing the \convex hull condition" of Cheung and Remmen. An essential point, which we dwell on at length, is precisely defining what we mean by gauge and global symmetries in the bulk and boundary. -

The Prospect of Immortality

Robert C. W. Ettinger__________The Prospect Of Immortality Contents Preface by Jean Rostand Preface by Gerald J. Gruman Foreword Chapter 1. Frozen Death, Frozen Sleep, and Some Consequences Suspended Life and Suspended Death Future and Present Options After a Moment of Sleep Problems and Side Effects Chapter II. The Effects of Freezing and Cooling Long-term Storage Successes in Freezing Animals and Tissues The Mechanism of Freezing Damage Frostbite The Action of Protective Agents The Persistence of Memory after Freezing The Extent of Freezing Damage Rapid Freezing and Perfusion Possibilities The Limits of Delay in Treatment The Limits of Delay in Cooling and Freezing Maximum and Optimum Storage Temperature Radiation Hazard Page 1 Robert Ettinger – All Rights Reserved www.cryonics.org Robert C. W. Ettinger__________The Prospect Of Immortality Chapter III. Repair and Rejuvenation Revival after Clinical Death Mechanical Aids and Prostheses Transplants Organ Culture and Regeneration Curing Old Age Chapter IV. Today's Choices The Outer Limits of Optimism Preserving Samples of Ourselves Preserving the Information Organization and Organizations Emergency and Austerity Freezing Freezing with Medical Cooperation Individual Responsibility: Dying Children Husbands and Wives, Aged Parents and Grandparents Chapter V. Freezers and Religion Revival of the Dead: Not a New Problem The Question of God's Intentions The Riddle of Soul Suicide Is a Sin God's Image and Religious Adaptability Added Time for Growth and Redemption Conflict with Revelation The Threat of Materialism Perspective Chapter VI. Freezers and the Law Freezers and Public Decency Definitions of Death; Rights and Obligations of the Frozen Life Insurance and Suicide Mercy Killings Murder Widows, Widowers, and Multiple Marriages Cadavers as Citizens Potter's Freezer and Umbrellas Page 2 Robert Ettinger – All Rights Reserved www.cryonics.org Robert C. -

A Time-Symmetric Formulation of Quantum Entanglement

entropy Article A Time-Symmetric Formulation of Quantum Entanglement Michael B. Heaney Independent Researcher, 3182 Stelling Drive, Palo Alto, CA 94303, USA; [email protected] Abstract: I numerically simulate and compare the entanglement of two quanta using the conventional formulation of quantum mechanics and a time-symmetric formulation that has no collapse postulate. The experimental predictions of the two formulations are identical, but the entanglement predictions are significantly different. The time-symmetric formulation reveals an experimentally testable discrepancy in the original quantum analysis of the Hanbury Brown–Twiss experiment, suggests solutions to some parts of the nonlocality and measurement problems, fixes known time asymmetries in the conventional formulation, and answers Bell’s question “How do you convert an ’and’ into an ’or’?” Keywords: quantum foundations; entanglement; time-symmetric; Hanbury Brown–Twiss (HBT); Einstein–Podolsky–Rosen (EPR); configuration space 1. Introduction Smolin says “the second great problem of contemporary physics [is to] resolve the problems in the foundations of quantum physics” [1]. One of these problems is quantum entanglement, which is at the heart of both new quantum information technologies [2] and old paradoxes in the foundations of quantum mechanics [3]. Despite significant effort, a comprehensive understanding of quantum entanglement remains elusive [4]. In this paper, I compare how the entanglement of two quanta is explained by the conventional formulation of quantum mechanics [5–7] and by a time-symmetric formulation that has Citation: Heaney, M.B. A no collapse postulate. The time-symmetric formulation and its numerical simulations Time-Symmetric Formulation of can facilitate the development of new insights and physical intuition about entanglement. -

Promises, Not Promises: Tomorrow Vs. Forever January 19, 2020 Ted Cunningham

Promises, Not Promises: Tomorrow vs. Forever January 19, 2020 Ted Cunningham 1. We are not promised tomorrow, but we are promised what? How much and when do you focus on God’s actual promise? 2. Have you ever clung to false promises that you thought were Christian? Please share. 3. Read James 4:13-16 Now listen, you who say, “Today or tomorrow we will go to this or that city, spend a year there, carry on business and make money.” 14 Why, you do not even know what will happen tomorrow. What is your life? You are a mist that appears for a little while and then vanishes. 15 Instead, you ought to say, “If it is the Lord’s will, we will live and do this or that.” 16 As it is, you boast in your arrogant schemes. All such boasting is evil. (NIV) Planning in and of itself is not wrong, but what type of planning is wrong? Are you ever tempted to do this type of planning? How can you change your thinking about future plans? 4. What are some of the word pictures or metaphors used in Scripture to depict the shortness of life? Would you live differently if you felt you were almost out of time? List some specific ways. 5. How is planning affected by the sovereignty of God? Read the following proverbs. Proverbs 16:9 In their hearts humans plan their course, but the Lord establishes their steps. (NIV) Proverbs 19:21 Many are the plans in a person’s heart, but it is the Lord’s purpose that prevails. -

Symmetries Come and Go

Symmetries Come and Go Nathan Seiberg, IAS Common in physics • Today’s signal is tomorrow’s background • Today’s new deep concepts are tomorrow’s derived consequences Examples: • The periodic table ← Quantum Mechanics ← ??? • Kepler’s laws ← Newton’s gravity ← General relativity ← String theory? • Many others This talk: color and gauge symmetry Physicists love symmetries • Crystallography • Lorentz • Flavor 푆푈(2), 푆푈(3) – Consequence of light quarks. Quarks are deep. • Color – Gauge symmetry is deep Gauge symmetry is deep • Largest symmetry (a group for each point in spacetime) • Useful in making the theory manifestly Lorentz invariant, unitary and local (and hence causal) • Appears in • Maxwell theory, the Standard Model • General Relativity • Many condensed matter systems • Deep mathematics (fiber bundles) But • Because of Gauss law the Hilbert space is gauge invariant. (More precisely, it is invariant under small gauge transformation; large gauge transformations are central.) • Hence: gauge symmetry is not a symmetry. • It does not act on anything. • A better phrase is gauge redundancy. Gauge symmetry can appear trivial • Start with an arbitrary system and consider some transformation, say a 푈(1) phase rotation on some fields. It is not a symmetry. • Introduce a Stueckelberg field 휙 푥 , which transforms under the 푈(1) by a shift. • Next, multiply every non-invariant term by an appropriate phase 푒푖 휙 푥 , such that the system has a local 푈(1) gauge symmetry. • Clearly, this is not a fundamental symmetry. Gauge symmetries cannot break • Not a symmetry and hence cannot break • For spontaneous symmetry breaking we need an infinite number of degrees of freedom transforming under the symmetry. -

Contact Us What They Say

What They Say... Contact Us Preparing Children for Today, Tomorrow... Forever INTERSTATE TO 40 N LUTHER ST. ELS DOWNTOWN WILBURN RD. INTERSTATE WILBURN 240 INTERSTATE FUTURE 26 Sonic ® PATTON AVE. Swannanoa Cleaners H A Y Exxon WOO INTERSTATE Exit 44 D R 40 D. Reasons our students INTERSTATE TO 26 love Emmanuel… *not to scale v “I love Emmanuel Lutheran School because The secluded Emmanuel I learn about God and Jesus.” Lutheran School campus is v “I love my school because it’s small. I know conveniently located in West Asheville. everybody and I have good friends.” v “I like it here because there are a lot of activities to do after school.” Reasons our parents THER L LU AN love Emmanuel… E S U C N UTHER H L A A v “I was looking for a secure place for my child to EL N O S M U C O receive a Christ-centered education and I found M N H L A E it here at Emmanuel Lutheran.” O M v O “My child is more engaged in learning becasue M L E of the technology and iPads in the classroom.” E st. 1958 v “In addition to the education, it’s become a E second family community for us where families st. 1958 are our friends and we all support each other.” Emmanuel Lutheran School v “The teachers and principal really care about 51 Wilburn Place – Asheville, NC 28806 Asheville, North Carolina my child.” 828.281.8182 Building a Strong Christian A member congregation Foundation from Infant Care www.EmmanuelLutheranSchool.org the Lutheran Church through 8th Grade Missouri Synod [email protected] Preparing Children, for Today, Tomorrow.. -

When Tomorrow Starts Without Me Erica Shea Liupaeter When

When Tomorrow Starts Without Me Erica Shea Liupaeter When tomorrow starts without me, and I'm not there to see; If the sun should rise and find your eyes, all filled with tears for me; I wish so much you wouldn't cry, the way you did today, while thinking of the many things, we didn't get to say. I know how much you love me, as much as I love you, and each time that you think of me, I know you'll miss me too; But when tomorrow starts without me, please try to understand, that an Angel came and called my name, and took me by the hand, and said my place was ready, in heaven far above, and that I'd have to leave behind, all those I dearly love. But as I turned to walk away, a tear fell from my eye, for all life, I'd always thought, I didn't want to die. I had so much to live for, so much yet to do, it seemed almost impossible, that I was leaving you. I thought of all the yesterdays, the good ones and the bad, I thought of all the love we shared, and all the fun we had. If I could relive yesterday, just even for awhile, I'd say goodbye and kiss you and maybe see you smile. But then I fully realized, that this could never be, for emptiness and memories, would take the place of me. And when I thought of worldly things, I might miss come tomorrow, I thought of you, and when I did, my heart was filled with sorrow. -

Do the Causal Principles of Modern Physics Contradict Causal Anti-Fundamentalism?

June 4, 2005. Rev. June 10,17, 05. Do the Causal Principles of Modern Physics Contradict Causal Anti-Fundamentalism? John D. Norton1 Department of History and Philosophy of Science University of Pittsburgh Pittsburgh PA www.pitt.edu/~jdnorton To appear in Causality: Historical and Contemporary. (provisional title) eds. P. K. Machamer and G. Wolters, University of Pittsburgh Press In Norton(2003), it was urged that the world does not conform at a fundamental level to some robust principle of causality. To defend this view, I now argue that the causal notions and principles of modern physics do not express some universal causal principle, brought to light by discoveries in physics. Rather they merely assert that, according to relativity theory, spacetime has an invariant velocity, that of light; and that theories of matter admit no propagations faster than light. 1 These remarks were prepared as a reaction to Jeremy Butterfield’s ,“Spacetime as a Causal Set: A Philosopher’s Introduction,” presented at the Seventh Meeting of the Pittburgh-Konstanz Colloquium in the Philosophy of Science, Causation: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives, May 26-29, 2005, Konstanz. I thank Jeremy for his stimulating talk and comments; Miklos Redei and the participants in the conference for their helpful reactions and discussion; and Deutsche Bahn, Schweizerische Bundesbahnen and Trenitalia for providing the rail service between Konstanz, Zurich, Milan, Florence and Turin on which this note was drafted. 1 1. Introduction In Norton (2003), I outlined a form of skepticism about causation called “causal anti- fundamentalism.” Its central idea is that the structure of the world is to be discovered empirically; it is not to be legislated in advance by metaphysical principles, such as a law of causation or a principle of causality. -

Information, Physics, Quantum: the Search for Links

19 INFORMATION, PHYSICS, QUANTUM: THE SEARCH FOR LINKS John Archibald Wheeler * t Abstract This report reviews what quantum physics and information theory have to tell us about the age-old question, How come existence? No escape is evident from four conclusions: (1) The world cannot be a giant machine, ruled by any preestablished continuum physical law. (2) There is no such thing at the microscopic level as space or time or spacetime continuum. (3) The familiar probability function or functional, and wave equation or functional wave equation, of standard quantum theory provide mere continuum idealizations and by reason of this circumstance conceal the information-theoretic source from which they derive. (4) No element in the description of physics shows itself as closer to primordial than the elementary quantum phenomenon, that is, the elementary device-intermediated act of posing a yes-no physical question and eliciting an answer or, in brief, the elementary act of observer-participancy. Otherwise stated, every physical quantity, every it, derives its ultimate significance from bits, binary yes-or-no indications, a conclusion which we epitomize in the phrase, it from bit. 19.1 Quantum Physics Requires a New View of Reality Revolution in outlook though Kepler, Newton, and Einstein brought us [1-4], and still more startling the story of life [5-7] that evolution forced upon an unwilling world, the ultimate shock to preconceived ideas lies ahead, be it a decade hence, a century or a millenium. The overarching principle of 20th-century physics,