A Short Review on the Intranasal Delivery of Diazepam for Treating Acute Repetitive Seizures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Intranasal and Rectal Diazepam for Rescue Therapy: Assessment of Pharmacokinetics and Tolerability a Dissertation Submitted to T

INTRANASAL AND RECTAL DIAZEPAM FOR RESCUE THERAPY: ASSESSMENT OF PHARMACOKINETICS AND TOLERABILITY A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY VIJAY DEEP IVATURI IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY ADVISER: JAMES. C. CLOYD DECEMBER 2010 © VIJAY DEEP IVATURI 2010 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis was carried out at the Center for Orphan Drug Research, Department of Experimental and Clinical Pharmacology, College of Pharmacy, University of Minnesota, United States. I would like to thank the following persons who have all contributed to this thesis and have been important to me throughout my time as a research student; My supervisor/adviser Professor James Cloyd for giving me the opportunity to join the Orphan Drug Research group. Thank you for sharing your vast knowledge and enthusiasm about research. Thanks for all the care and consideration that you and Mrs. Cloyd have always shown and for letting me experience a family away from home. I also appreciate you letting me pursue my personal interest in the application of Pharmacometrics into our research projects and for letting me take a break from my studies to go to GlaxoSmithKline and try a world outside the university. My second committee member Dr. Robert Kriel for showing interest in my work and always questioning the usability and necessity of things and for also being the first to give comments back on reports and manuscripts. Thanks for sharing your expert clinical knowledge and giving me an opportunity to do a clinical clerkship at Hennipen County Medical Center and Gillette Children’s Hospital. -

Diazepam - Alcohol Withdrawal

Diazepam - alcohol withdrawal Why have I been prescribed diazepam? If a person stops drinking alcohol after a time of drinking too much they can experience withdrawal effects. These include “the shakes”, sweating, having fits, seeing things which are not there (hallucinations) and feeling anxious and low in mood. They can feel wound up and find it difficult to sleep. These withdrawal effects can be very uncomfortable and in extreme cases can be dangerous if they persist into “DTs” (delirium tremens). Diazepam is used to help reduce these withdrawal symptoms. It relieves anxiety and tension and aids sleep. Diazepam can also prevent fits. It controls the withdrawal symptoms until the body is free of alcohol and has settled down. This usually takes three to seven days from the time you stop drinking. What exactly is diazepam? Diazepam is a benzodiazepine. This group of medicines is also called anxiolytics or minor tranquillisers. Diazepam has many uses. It can be used to reduce symptoms of anxiety and insomnia, as well as to help people come off alcohol. Diazepam should only be prescribed and taken as a short course. Is diazepam safe to take? Diazepam is safe to take for a short period of time, but it doesn’t suit everyone. Below are a few conditions where diazepam may be less suitable. If any of these apply to you please tell your doctor or key-worker. If you have depression or a mental illness If you have lung disease or breathing problems, or suffer from liver or kidney trouble If you take any other medicines or drugs, including those on prescription and bought from a chemist If you take illicit drugs bought “on the street” If you are pregnant or breast-feeding What is the usual dose of diazepam? The dose of diazepam will usually be started at 10-20mg four times a day. -

What Is Diazepam?

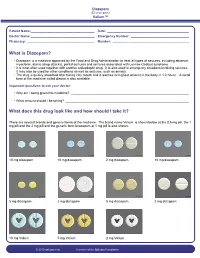

Diazepam (Di-a-ze-pam) Valium™ Patient Name: ___________________________________ Date: _____________________________________________ Doctor Name: ___________________________________ Emergency Number: ________________________________ Pharmacy: _____________________________________ Number: __________________________________________ What is Diazepam? • Diazepam is a medicine approved by the Food and Drug Administration to treat all types of seizures, including absence, myoclonic, atonic (drop attacks), partial seizures and seizures associated with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome. • It is most often used together with another antiepileptic drug. It is also used in emergency situations involving seizures. It may also be used for other conditions as well as seizures, such as anxiety. • The drug is quickly absorbed after taking it by mouth and it reaches its highest amount in the body in 1-2 hours. A rectal form of the medicine called diastat is also available. Important questions to ask your doctor: • Why am I being given this medicine? _________________________________________________________________ • What amount should I be taking? ____________________________________________________________________ What does this drug look like and how should I take it? There are several brands and generic forms of the medicine. The brand name Valium is shown below at the 0.5 mg pill, the 1 mg pill and the 2 mg pill and the generic form lorazepam at 1 mg pill is also shown. 10 mg diazepam 10 mg diazepam 2 mg diazepam 10 mg diazepam 5 mg diazepam 2 mg diazepam 5 mg diazepam 2 mg diazepam 10 mg Valium 5 mg Valium 2 mg Valium © 2010 epilepsy.com A service of the Epilepsy Foundation Diazepam (Di-a-ze-pam) Valium™ Frequently Asked Questions: How do I take Diazepam? To use the tablet form: chew tablets and swallow or swallow the tablet whole. -

Intranasal Drug Delivery System- a Glimpse to Become Maestro

Journal of Applied Pharmaceutical Science 01 (03); 2011: 34-44 Received: 17-05-2011 Revised on: 18-05-2011 Intranasal drug delivery system- A glimpse to become Accepted: 21-05-2011 maestro Shivam Upadhyay, Ankit Parikh, Pratik Joshi, U M Upadhyay and N P Chotai, ABSTRACT Intranasal drug delivery – which has been practiced for thousands of years, has been given a new lease of life. It is a useful delivery method for drugs that are active in low doses and Shivam Upadhyay, Ankit Parikh, Pratik show no minimal oral bioavailability such as proteins and peptides. One of the reasons for the low Joshi, N P Chotai, Dept of Pharmaceutics, A R Collage of degree of absorption of peptides and proteins via the nasal route is rapid movement away from the Pharmacy, V.V.Nagar, Gujarat,India. absorption site in the nasal cavity due to the Mucociliary Clearance mechanism. The nasal route circumvents hepatic first pass elimination associated with the oral delivery: it is easily accessible and suitable for self-medication. The large surface area of the nasal mucosa affords a rapid onset of therapeutic effect, potential for direct-to-central nervous system delivery, no first-pass metabolism, and non-invasiveness; all of which may maximize patient convenience, comfort, and compliance. IN delivery is non -invasive, essentially painless, does not require sterile preparation, U M Upadhyay and is easily and readily administered by the patient or a physician, e.g., in an emergency setting. Sigma Institute of Pharmacy, Baroda, Furthermore, the nasal route may offer improved delivery for “non-Lipinski” drugs. -

)&F1y3x PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX to THE

)&f1y3X PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX TO THE HARMONIZED TARIFF SCHEDULE )&f1y3X PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX TO THE TARIFF SCHEDULE 3 Table 1. This table enumerates products described by International Non-proprietary Names (INN) which shall be entered free of duty under general note 13 to the tariff schedule. The Chemical Abstracts Service (CAS) registry numbers also set forth in this table are included to assist in the identification of the products concerned. For purposes of the tariff schedule, any references to a product enumerated in this table includes such product by whatever name known. Product CAS No. Product CAS No. ABAMECTIN 65195-55-3 ACTODIGIN 36983-69-4 ABANOQUIL 90402-40-7 ADAFENOXATE 82168-26-1 ABCIXIMAB 143653-53-6 ADAMEXINE 54785-02-3 ABECARNIL 111841-85-1 ADAPALENE 106685-40-9 ABITESARTAN 137882-98-5 ADAPROLOL 101479-70-3 ABLUKAST 96566-25-5 ADATANSERIN 127266-56-2 ABUNIDAZOLE 91017-58-2 ADEFOVIR 106941-25-7 ACADESINE 2627-69-2 ADELMIDROL 1675-66-7 ACAMPROSATE 77337-76-9 ADEMETIONINE 17176-17-9 ACAPRAZINE 55485-20-6 ADENOSINE PHOSPHATE 61-19-8 ACARBOSE 56180-94-0 ADIBENDAN 100510-33-6 ACEBROCHOL 514-50-1 ADICILLIN 525-94-0 ACEBURIC ACID 26976-72-7 ADIMOLOL 78459-19-5 ACEBUTOLOL 37517-30-9 ADINAZOLAM 37115-32-5 ACECAINIDE 32795-44-1 ADIPHENINE 64-95-9 ACECARBROMAL 77-66-7 ADIPIODONE 606-17-7 ACECLIDINE 827-61-2 ADITEREN 56066-19-4 ACECLOFENAC 89796-99-6 ADITOPRIM 56066-63-8 ACEDAPSONE 77-46-3 ADOSOPINE 88124-26-9 ACEDIASULFONE SODIUM 127-60-6 ADOZELESIN 110314-48-2 ACEDOBEN 556-08-1 ADRAFINIL 63547-13-7 ACEFLURANOL 80595-73-9 ADRENALONE -

Nasal Delivery of Aqueous Corticosteroid Solutions Nasale Abgabe Von Wässrigen Corticosteroidlösungen Administration Nasale De Solutions Aqueuses De Corticostéroïdes

(19) TZZ _¥__T (11) EP 2 173 169 B1 (12) EUROPEAN PATENT SPECIFICATION (45) Date of publication and mention (51) Int Cl.: of the grant of the patent: A01N 43/04 (2006.01) A61K 31/715 (2006.01) 21.05.2014 Bulletin 2014/21 (86) International application number: (21) Application number: 08781216.0 PCT/US2008/068872 (22) Date of filing: 30.06.2008 (87) International publication number: WO 2009/003199 (31.12.2008 Gazette 2009/01) (54) NASAL DELIVERY OF AQUEOUS CORTICOSTEROID SOLUTIONS NASALE ABGABE VON WÄSSRIGEN CORTICOSTEROIDLÖSUNGEN ADMINISTRATION NASALE DE SOLUTIONS AQUEUSES DE CORTICOSTÉROÏDES (84) Designated Contracting States: • ZIMMERER, Rupert, O. AT BE BG CH CY CZ DE DK EE ES FI FR GB GR Lawrence, KS 66047 (US) HR HU IE IS IT LI LT LU LV MC MT NL NO PL PT • SIEBERT, John, M. RO SE SI SK TR Olathe, KS 66061-7470 (US) (30) Priority: 28.06.2007 PCT/US2007/072387 (74) Representative: Dörries, Hans Ulrich et al 29.06.2007 PCT/US2007/072442 df-mp Dörries Frank-Molnia & Pohlman Patentanwälte Rechtsanwälte PartG mbB (43) Date of publication of application: Theatinerstrasse 16 14.04.2010 Bulletin 2010/15 80333 München (DE) (73) Proprietor: CyDex Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (56) References cited: Lenexa, KS 66214 (US) WO-A1-2005/065649 US-A1- 2006 194 840 US-A1- 2007 020 299 US-A1- 2007 020 330 (72) Inventors: • PIPKIN, James, D. Lawrence, KS 66049 (US) Note: Within nine months of the publication of the mention of the grant of the European patent in the European Patent Bulletin, any person may give notice to the European Patent Office of opposition to that patent, in accordance with the Implementing Regulations. -

Scope and Limitations on Aerosol Drug Delivery for the Treatment of Infectious Respiratory Diseases Hana Douafer, Jean Michel Brunel, Véronique Andrieu

Scope and limitations on aerosol drug delivery for the treatment of infectious respiratory diseases Hana Douafer, Jean Michel Brunel, Véronique Andrieu To cite this version: Hana Douafer, Jean Michel Brunel, Véronique Andrieu. Scope and limitations on aerosol drug delivery for the treatment of infectious respiratory diseases. Journal of Controlled Release, Elsevier, 2020, 325, pp.276-292. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2020.07.002. hal-03084998 HAL Id: hal-03084998 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03084998 Submitted on 8 Jan 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Scope and limitations on aerosol drug delivery for the treatment of infectious respiratory diseases Hana Douafer, PhD1, Véronique Andrieu, PhD2 and Jean Michel Brunel, PhD1* Corresponding Author: Jean-Michel Brunel, PhD 1 Aix Marseille Univ, INSERM, SSA, MCT, 13385 Marseille, France. E-mail : [email protected]. Phone : (+33) 689271645 2Aix Marseille Univ, IRD, APHM, MEPHI, IHU Méditerranée Infection, Faculté de Médecine et de Pharmacie, 13385 Marseille, France. Abstract: The rise of antimicrobial resistance has created an urgent need for the development of new methods for antibiotics delivery to patients with pulmonary infections in order to mainly increase the effectiveness of the drugs administration, to minimize the risk of emergence of resistant strains, and to prevent patients reinfection. -

Intranasal Medication Administration – Adult/Pediatric – Inpatient/Ambulatory/Primary Care Clinical Practice Guideline

Intranasal Medication Administration – Adult/Pediatric – Inpatient/Ambulatory/Primary Care Clinical Practice Guideline Note: Active Table of Contents – Click to follow link Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................ 3 Scope ..................................................................................................................................................... 7 Methodology ......................................................................................................................................... 7 Definitions ............................................................................................................................................. 8 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................... 8 Recommendations ................................................................................................................................. 9 General Recommendations for Intranasal Administration ....................................................................... 9 Drug-Specific Practice Recommendations ............................................................................................. 10 UW Health Implementation ................................................................................................................. 14 Appendix A. Evidence Grading Scheme ................................................................................................ -

Pharmaceuticals Appendix

)&f1y3X PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX TO THE HARMONIZED TARIFF SCHEDULE )&f1y3X PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX TO THE TARIFF SCHEDULE 3 Table 1. This table enumerates products described by International Non-proprietary Names (INN) which shall be entered free of duty under general note 13 to the tariff schedule. The Chemical Abstracts Service (CAS) registry numbers also set forth in this table are included to assist in the identification of the products concerned. For purposes of the tariff schedule, any references to a product enumerated in this table includes such product by whatever name known. Product CAS No. Product CAS No. ABAMECTIN 65195-55-3 ADAPALENE 106685-40-9 ABANOQUIL 90402-40-7 ADAPROLOL 101479-70-3 ABECARNIL 111841-85-1 ADEMETIONINE 17176-17-9 ABLUKAST 96566-25-5 ADENOSINE PHOSPHATE 61-19-8 ABUNIDAZOLE 91017-58-2 ADIBENDAN 100510-33-6 ACADESINE 2627-69-2 ADICILLIN 525-94-0 ACAMPROSATE 77337-76-9 ADIMOLOL 78459-19-5 ACAPRAZINE 55485-20-6 ADINAZOLAM 37115-32-5 ACARBOSE 56180-94-0 ADIPHENINE 64-95-9 ACEBROCHOL 514-50-1 ADIPIODONE 606-17-7 ACEBURIC ACID 26976-72-7 ADITEREN 56066-19-4 ACEBUTOLOL 37517-30-9 ADITOPRIME 56066-63-8 ACECAINIDE 32795-44-1 ADOSOPINE 88124-26-9 ACECARBROMAL 77-66-7 ADOZELESIN 110314-48-2 ACECLIDINE 827-61-2 ADRAFINIL 63547-13-7 ACECLOFENAC 89796-99-6 ADRENALONE 99-45-6 ACEDAPSONE 77-46-3 AFALANINE 2901-75-9 ACEDIASULFONE SODIUM 127-60-6 AFLOQUALONE 56287-74-2 ACEDOBEN 556-08-1 AFUROLOL 65776-67-2 ACEFLURANOL 80595-73-9 AGANODINE 86696-87-9 ACEFURTIAMINE 10072-48-7 AKLOMIDE 3011-89-0 ACEFYLLINE CLOFIBROL 70788-27-1 -

First Clinical Trials of the Inhaled Enac Inhibitor BI 1265162 in Healthy Volunteers

Early View Original article First clinical trials of the inhaled ENaC inhibitor BI 1265162 in healthy volunteers Alison Mackie, Juliane Rascher, Marion Schmid, Verena Endriss, Tobias Brand, Wolfgang Seibold Please cite this article as: Mackie A, Rascher J, Schmid M, et al. First clinical trials of the inhaled ENaC inhibitor BI 1265162 in healthy volunteers. ERJ Open Res 2020; in press (https://doi.org/10.1183/23120541.00447-2020). This manuscript has recently been accepted for publication in the ERJ Open Research. It is published here in its accepted form prior to copyediting and typesetting by our production team. After these production processes are complete and the authors have approved the resulting proofs, the article will move to the latest issue of the ERJOR online. Copyright ©ERS 2020. This article is open access and distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial Licence 4.0. First clinical trials of the inhaled ENaC inhibitor BI 1265162 in healthy volunteers Authors Alison Mackie;1 Juliane Rascher;2 Marion Schmid;1 Verena Endriss;1 Tobias Brand;1 Wolfgang Seibold1 1Boehringer Ingelheim, Biberach an der Riss, Germany. 2SocraMetrics GmbH, Erfurt, Germany, on behalf of BI Pharma GmbH & Co. KG, Biberach an der Riss, Germany Corresponding author: Alison Mackie Boehringer Ingelheim Pharma GmbH & Co. KG, Biberach an der Riss Germany Email: [email protected] Tel: +49735154145536 Journal suggestion: ERJ Open Research Short title: BI 1265162 in Phase I trials Keywords: Cystic fibrosis, ENaC inhibitor, Phase I, airway surface hydration, mucus clearance Abstract (250 words/250 words permitted) Background: Inhibition of the epithelial sodium channel (ENaC) represents a mutation-agnostic therapeutic approach to restore airway surface liquid hydration and mucociliary clearance in patients with cystic fibrosis. -

Calculating Equivalent Doses of Oral Benzodiazepines

Calculating equivalent doses of oral benzodiazepines Background Benzodiazepines are the most commonly used anxiolytics and hypnotics (1). There are major differences in potency between different benzodiazepines and this difference in potency is important when switching from one benzodiazepine to another (2). Benzodiazepines also differ markedly in the speed in which they are metabolised and eliminated. With repeated daily dosing accumulation occurs and high concentrations can build up in the body (mainly in fatty tissues) (2). The degree of sedation that they induce also varies, making it difficult to determine exact equivalents (3). Answer Advice on benzodiazepine conversion NB: Before using Table 1, read the notes below and the Limitations statement at the end of this document. Switching benzodiazepines may be advantageous for a variety of reasons, e.g. to a drug with a different half-life pre-discontinuation (4) or in the event of non-availability of a specific benzodiazepine. With relatively short-acting benzodiazepines such as alprazolam and lorazepam, it is not possible to achieve a smooth decline in blood and tissue concentrations during benzodiazepine withdrawal. These drugs are eliminated fairly rapidly with the result that concentrations fluctuate with peaks and troughs between each dose. It is necessary to take the tablets several times a day and many people experience a "mini-withdrawal", sometimes a craving, between each dose. For people withdrawing from these potent, short-acting drugs it has been advised that they switch to an equivalent dose of a benzodiazepine with a long half life such as diazepam (5). Diazepam is available as 2mg tablets which can be halved to give 1mg doses. -

Drugs of Abuse: Benzodiazepines

Drugs of Abuse: Benzodiazepines What are Benzodiazepines? Benzodiazepines are central nervous system depressants that produce sedation, induce sleep, relieve anxiety and muscle spasms, and prevent seizures. What is their origin? Benzodiazepines are only legally available through prescription. Many abusers maintain their drug supply by getting prescriptions from several doctors, forging prescriptions, or buying them illicitly. Alprazolam and diazepam are the two most frequently encountered benzodiazepines on the illicit market. Benzodiazepines are What are common street names? depressants legally available Common street names include Benzos and Downers. through prescription. Abuse is associated with What do they look like? adolescents and young The most common benzodiazepines are the prescription drugs ® ® ® ® ® adults who take the drug Valium , Xanax , Halcion , Ativan , and Klonopin . Tolerance can orally or crush it up and develop, although at variable rates and to different degrees. short it to get high. Shorter-acting benzodiazepines used to manage insomnia include estazolam (ProSom®), flurazepam (Dalmane®), temazepam (Restoril®), Benzodiazepines slow down and triazolam (Halcion®). Midazolam (Versed®), a short-acting the central nervous system. benzodiazepine, is utilized for sedation, anxiety, and amnesia in critical Overdose effects include care settings and prior to anesthesia. It is available in the United States shallow respiration, clammy as an injectable preparation and as a syrup (primarily for pediatric skin, dilated pupils, weak patients). and rapid pulse, coma, and possible death. Benzodiazepines with a longer duration of action are utilized to treat insomnia in patients with daytime anxiety. These benzodiazepines include alprazolam (Xanax®), chlordiazepoxide (Librium®), clorazepate (Tranxene®), diazepam (Valium®), halazepam (Paxipam®), lorzepam (Ativan®), oxazepam (Serax®), prazepam (Centrax®), and quazepam (Doral®).