Kings of the Chessboard Paul Van Der Sterren

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Combinatorics on the Chessboard

Combinatorics on the Chessboard Interactive game: 1. On regular chessboard a rook is placed on a1 (bottom-left corner). Players A and B take alternating turns by moving the rook upwards or to the right by any distance (no left or down movements allowed). Player A makes the rst move, and the winner is whoever rst reaches h8 (top-right corner). Is there a winning strategy for any of the players? Solution: Player B has a winning strategy by keeping the rook on the diagonal. Knight problems based on invariance principle: A knight on a chessboard has a property that it moves by alternating through black and white squares: if it is on a white square, then after 1 move it will land on a black square, and vice versa. Sometimes this is called the chameleon property of the knight. This is related to invariance principle, and can be used in problems, such as: 2. A knight starts randomly moving from a1, and after n moves returns to a1. Prove that n is even. Solution: Note that a1 is a black square. Based on the chameleon property the knight will be on a white square after odd number of moves, and on a black square after even number of moves. Therefore, it can return to a1 only after even number of moves. 3. Is it possible to move a knight from a1 to h8 by visiting each square on the chessboard exactly once? Solution: Since there are 64 squares on the board, a knight would need 63 moves to get from a1 to h8 by visiting each square exactly once. -

A Package to Print Chessboards

chessboard: A package to print chessboards Ulrike Fischer November 1, 2020 Contents 1 Changes 1 2 Introduction 2 2.1 Bugs and errors.....................................3 2.2 Requirements......................................4 2.3 Installation........................................4 2.4 Robustness: using \chessboard in moving arguments..............4 2.5 Setting the options...................................5 2.6 Saving optionlists....................................7 2.7 Naming the board....................................8 2.8 Naming areas of the board...............................8 2.9 FEN: Forsyth-Edwards Notation...........................9 2.10 The main parts of the board..............................9 3 Setting the contents of the board 10 3.1 The maximum number of fields........................... 10 1 3.2 Filling with the package skak ............................. 11 3.3 Clearing......................................... 12 3.4 Adding single pieces.................................. 12 3.5 Adding FEN-positions................................. 13 3.6 Saving positions..................................... 15 3.7 Getting the positions of pieces............................ 16 3.8 Using saved and stored games............................ 17 3.9 Restoring the running game.............................. 17 3.10 Changing the input language............................. 18 4 The look of the board 19 4.1 Units for lengths..................................... 19 4.2 Some words about box sizes.............................. 19 4.3 Margins......................................... -

Sample Pages

01-01 Cover -March 2021_Layout 1 17/02/2021 17:19 Page 1 03-03 Contents_Chess mag - 21_6_10 18/02/2021 09:47 Page 3 Chess Contents Founding Editor: B.H. Wood, OBE. M.Sc † Executive Editor: Malcolm Pein Editorial....................................................................................................................4 Editors: Richard Palliser, Matt Read Malcolm Pein on the latest developments in the game Associate Editor: John Saunders Subscriptions Manager: Paul Harrington 60 Seconds with...Jorden van Foreest.......................................................7 Twitter: @CHESS_Magazine We catch up with the man of the moment after Wijk aan Zee Twitter: @TelegraphChess - Malcolm Pein Website: www.chess.co.uk Dutch Dominance.................................................................................................8 The Tata Steel Masters went ahead. Yochanan Afek reports Subscription Rates: United Kingdom How Good is Your Chess?..............................................................................18 1 year (12 issues) £49.95 Daniel King presents one of the games of Wijk,Wojtaszek-Caruana 2 year (24 issues) £89.95 3 year (36 issues) £125 Up in the Air ........................................................................................................21 Europe There’s been drama aplenty in the Champions Chess Tour 1 year (12 issues) £60 2 year (24 issues) £112.50 Howell’s Hastings Haul ...................................................................................24 3 year (36 issues) £165 David Howell ran -

53Rd WORLD CONGRESS of CHESS COMPOSITION Crete, Greece, 16-23 October 2010

53rd WORLD CONGRESS OF CHESS COMPOSITION Crete, Greece, 16-23 October 2010 53rd World Congress of Chess Composition 34th World Chess Solving Championship Crete, Greece, 16–23 October 2010 Congress Programme Sat 16.10 Sun 17.10 Mon 18.10 Tue 19.10 Wed 20.10 Thu 21.10 Fri 22.10 Sat 23.10 ICCU Open WCSC WCSC Excursion Registration Closing Morning Solving 1st day 2nd day and Free time Session 09.30 09.30 09.30 free time 09.30 ICCU ICCU ICCU ICCU Opening Sub- Prize Giving Afternoon Session Session Elections Session committees 14.00 15.00 15.00 17.00 Arrival 14.00 Departure Captains' meeting Open Quick Open 18.00 Solving Solving Closing Lectures Fairy Evening "Machine Show Banquet 20.30 Solving Quick Gun" 21.00 19.30 20.30 Composing 21.00 20.30 WCCC 2010 website: http://www.chessfed.gr/wccc2010 CONGRESS PARTICIPANTS Ilham Aliev Azerbaijan Stephen Rothwell Germany Araz Almammadov Azerbaijan Rainer Staudte Germany Ramil Javadov Azerbaijan Axel Steinbrink Germany Agshin Masimov Azerbaijan Boris Tummes Germany Lutfiyar Rustamov Azerbaijan Arno Zude Germany Aleksandr Bulavka Belarus Paul Bancroft Great Britain Liubou Sihnevich Belarus Fiona Crow Great Britain Mikalai Sihnevich Belarus Stewart Crow Great Britain Viktor Zaitsev Belarus David Friedgood Great Britain Eddy van Beers Belgium Isabel Hardie Great Britain Marcel van Herck Belgium Sally Lewis Great Britain Andy Ooms Belgium Tony Lewis Great Britain Luc Palmans Belgium Michael McDowell Great Britain Ward Stoffelen Belgium Colin McNab Great Britain Fadil Abdurahmanović Bosnia-Hercegovina Jonathan -

The Oldest Books on Modern Chess

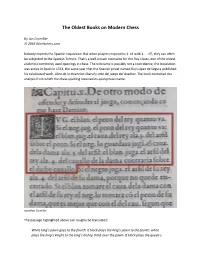

The Oldest Books on Modern Chess By Jon Crumiller © 2016 Worldchess.com Nobody expects the Spanish Inquisition. But when players respond to 1. e4 with 1. … e5, they can often be subjected to the Spanish Torture. That’s a well-known nickname for the Ruy López, one of the oldest and most commonly used openings in chess. The nickname is possibly not a coincidence; the Inquisition was active in Spain in 1561, the same year that the Spanish priest named Ruy López de Segura published his celebrated work, Libro de la Invencion liberal y Arte del juego del Axedrez. The book contained the analysis from which the chess opening received its eponymous name. Jonathan Crumiller The passage highlighted above can roughly be translated: White king’s pawn goes to the fourth. If black plays the king’s pawn to the fourth: white plays the king’s knight to the king’s bishop third, over the pawn. If black plays the queen’s knight to queen’s bishop third: white plays the king’s bishop to the fourth square of the contrary queen’s knight, opposed to that knight. Or in our modern chess language: 1. e4, e5 2. Nf3, Nc6 3. Bb5. Jonathan Crumiller On the right is how the Ruy López opening would have looked four centuries ago with a standard chess set and board in Spain. This Spanish chess set is one of my oldest complete sets (along with a companion wooden set of the same era). Jonathan Crumiller Here is the Ruy López as seen with that companion set displayed on a Spanish chessboard, also from the 1600’s. -

Carlsen, Fischer &

VER LAG DIE WERK STATT GÖTTIN GEN IN FOR MA TION Martin Breutigam Carlsen, Fischer & Co. The World Chess Champions from 1886 until today They were child prodigies and scientists, eccentrics and artists: the players who won the World Chess Championship in the last 130 years. This book portrays all of them: The American genius Bobby Fischer and his Russian opponent Boris Spassky (whose preparation for the “Match of the Century” in 1972 included playing tennis!). The Russian Vasily Smyslov who was not only good at chess but an excellent opera singer at that. And Norwegian poster boy Magnus Carlsen who has been dubbed the “Justin Bieber of chess”. Full of anecdotes and brilliant combinations, this book is a must read for any chess lover! The author Martin Breutigam, born 1965 in Bremen, Germany, is an International Master and a long-time Chess Bundesliga player. He works as a journalist for German newspapers Süddeutsche Zeitung and Tagesspiegel and has published several books and DVDs on chess. Sales points • Large target audience: This book addresses all lovers of chess, beginners as well as advanced players. • It’s the perfect gift for any chess fan. • Increasing popularity of chess in recent years – not least due to Magnus Carlsen. Martin Breutigam Carlsen, Fischer & Co. The World Chess Champions from 1886 until today 208 pages, 13,5 x 21,5 cm, paperback ISBN 978–3–7307–0287–1 Date of publication: October 2016 German retail price: 14,90 “ Rights available: all languages VER LAG DIE WERK STATT · Lotzestraße 22a · 37083 Göttingen · Tel. 0551/7896510 · Fax 78965125 E-Mail: [email protected] · Internet: www.werkstatt-verlag.de Foreign rights manager: Julia Vogt, Tel. -

Chess Mag - 21 6 10 18/09/2020 14:01 Page 3

01-01 Cover - October 2020_Layout 1 18/09/2020 14:00 Page 1 03-03 Contents_Chess mag - 21_6_10 18/09/2020 14:01 Page 3 Chess Contents Founding Editor: B.H. Wood, OBE. M.Sc † Executive Editor: Malcolm Pein Editorial....................................................................................................................4 Editors: Richard Palliser, Matt Read Malcolm Pein on the latest developments in the game Associate Editor: John Saunders Subscriptions Manager: Paul Harrington 60 Seconds with...Peter Wells.......................................................................7 Twitter: @CHESS_Magazine The acclaimed author, coach and GM still very much likes to play Twitter: @TelegraphChess - Malcolm Pein Website: www.chess.co.uk Online Drama .........................................................................................................8 Danny Gormally presents some highlights of the vast Online Olympiad Subscription Rates: United Kingdom Carlsen Prevails - Just ....................................................................................14 1 year (12 issues) £49.95 Nakamura pushed Magnus all the way in the final of his own Tour 2 year (24 issues) £89.95 Find the Winning Moves.................................................................................18 3 year (36 issues) £125 Can you do as well as the acclaimed field in the Legends of Chess? Europe 1 year (12 issues) £60 Opening Surprises ............................................................................................22 2 year (24 issues) £112.50 -

Vasily Smyslov

Vasily Smyslov Volume I The Early Years: 1921-1948 Andrey Terekhov Foreword by Peter Svidler Smyslov’s Endgames by Karsten Müller 2020 Russell Enterprises, Inc. Milford, CT USA 1 1 Vasily Smyslov Volume I The Early Years: 1921-1948 ISBN: 978-1-949859-24-9 (print) ISBN: 949859-25-6 (eBook) © Copyright 2020 Andrey Terekhov All Rights Reserved No part of this book may be used, reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any manner or form whatsoever or by any means, electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. Published by: Russell Enterprises, Inc. P.O. Box 3131 Milford, CT 06460 USA http://www.russell-enterprises.com [email protected] Cover by Fierce Ponies Printed in the United States of America 2 Table of Contents Introduction 6 Acknowledgments 9 Foreword by Peter Svidler 11 Signs and Symbols 13 Chapter 1. First Steps – 1935-37 14 Parents and Childhood 14 Chess Education at Home 18 The First Tournaments 22 The First Publications 26 The First Victories over Masters 34 Chapter 1: Games 41 Chapter 2. The Breakthrough Year – 1938 49 USSR Junior Championship 49 The First Adult Tournaments 53 The Higher Education Quandary 54 Candidate Master 56 1938 Moscow Championship 62 Chapter 2: Games 67 Chapter 3. The Young Master – 1939-40 80 1939 Leningrad/Moscow Training Tournament 80 The Run-Up to the 1940 USSR championship 87 Chapter 3: Games 91 Chapter 4. Third in the Soviet Union – 1940 118 World Politics and Chess 118 Pre-Tournament Forecasts 121 Round-By-Round Overview 126 After the Tournament 146 Chapter 4: Games 151 3 Chapter 5. -

Owen Mccoy on the Front Cover: Northwest Chess US Chess Master Owen Mccoy

orthwes $3.95 N t C h May 2018 e s s Chess News and Features from Oregon, Washington, and Idaho Owen McCoy On the front cover: Northwest Chess US Chess Master Owen McCoy. (See story pp. 4-7.) May 2018, Volume 72-05 Issue 844 Photo credit: Sarah McCoy. ISSN Publication 0146-6941 Published monthly by the Northwest Chess Board. On the back cover: POSTMASTER: Send address changes to the Office of Record: GM Julio Sadorra doing a pushup at Kerry Park on Northwest Chess c/o Orlov Chess Academy 4174 148th Ave NE, Queen Anne overlooking downtown Seattle. (Don’t try Building I, Suite M, Redmond, WA 98052-5164. this at home, kids!) Photo credit: Jacob Mayer. Periodicals Postage Paid at Seattle, WA USPS periodicals postage permit number (0422-390) Chesstoons: Chess cartoons drawn by local artist Brian Berger, NWC Staff of West Linn, Oregon. Editor: Jeffrey Roland, [email protected] Games Editor: Ralph Dubisch, [email protected] Submissions Publisher: Duane Polich, [email protected] Submissions of games (PGN format is preferable for games), Business Manager: Eric Holcomb, stories, photos, art, and other original chess-related content [email protected] are encouraged! Multiple submissions are acceptable; please indicate if material is non-exclusive. All submissions are Board Representatives subject to editing or revision. Send via U.S. Mail to: David Yoshinaga, Josh Sinanan, Jeffrey Roland, NWC Editor Jeffrey Roland, Adam Porth, Chouchanik Airapetian, 1514 S. Longmont Ave. Brian Berger, Duane Polich. Boise, Idaho 83706-3732 or via e-mail to: Entire contents ©2018 by Northwest Chess. All rights reserved. -

Calle Erlandsson CHESS PERIODICAL WANTS LIST Nyckelkroken 14, SE-22647 Lund Updated 20.7 2019 [email protected] Cell Phone +46 733 264 033

Calle Erlandsson CHESS PERIODICAL WANTS LIST Nyckelkroken 14, SE-22647 Lund updated 20.7 2019 [email protected] Cell phone +46 733 264 033 AUSTRIA ARBEITER-SCHACHZEITUNG [oct1921-sep1922; jan1926-dec1933; #12/1933 final issue?] 1921:1 2 3 1922:4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 1926:1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 1927:11 12 1928:2 3 4 5 8 9 10 11 12 1929:1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 INTERNATIONALE GALERIE MODERNER PROBLEM-KOMPONISTEN [jan1930-oct1930; #10 final issue] 1930:2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 KIEBITZ [1994->??] 1994:1 3-> NACHRICHTEN DES SCHACHVEREIN „HIETZING” [1931-1934; #3-4/1934 final issue?] 1931 1932:1 2 4 5 6 8 9 10 1933:4 7 1934:1 2 NÖ SCHACH [1978->] 1978 1979:1 2 4-> 1980-> ORAKEL [1940-19??; Das Magazin für Rätsel, Danksport, Philatelie, Schach und Humor, Wien; Editor: Maximilian Kraemer] 1940-1946 1947:1-4 6->? ÖSTERREICHISCHE LESEHALLE [1881-1896] 1881:1-12 1882:13-24 1883:25-36 1884:37-48 1885:49-60 1886 1887 1888 1889 1890 1891 1892 1893 1894 1895 1896 ÖSTERREICHISCHE SCHACHRUNDSCHAU [1922-1925] have a complete run ÖSTERREICHISCHE SCHACHZEITUNG [1872-1875 #1-63; 1935-1938; 1952-jan1971; #1/1971 final issue] 1872:1-18 1937:11 12 1938:2 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 SCHACH-AKTIV [1979->] 1979:3 4 2014:1-> SCHACH-MAGAZíN [1946-1951; superseded by Österreichische Schachzeitung] have a complete run WIENER SCHACHNACHRICHTEN [feb1992->?] 1992 1993 1994:1-6 9-12 1995:1-4 6-12 1996-> [Neue] WIENER SCHACHZEITUNG [jan1855-sep1855; jul1887-mar1888; jan1898-apr1916; mar1923- 1938; jul1948-aug1949] 1855:1-9 1887/88:1-9 1916:1/4© 5/8© Want publishers original bindings: 1898 1915 1938 BELARUS AMADEUS [1992->??; Zhurnal po Shakhmatnoij Kompozitzii] 1992-> SHAKHMATY, SHASJKI v BSSR [dec1979-oct1990] 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 SHAKHMATY [jun2004->; quarterly] 2003:1 2 2004:6 2006:11 13 14 2007:15 16 17 18 2008:19 20 21 22 2009->? SHAKHMATY-PLJUS [2003->; quarterly] 2003:1 2004:4 5 2005:6 7 8 9 2006:10-> BELGIUM [BULLETIN] A.J.E.C. -

History of Chess from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia for the Book by H

History of chess From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia For the book by H. J. R. Murray, see A History of Chess. Real-size resin reproductions of the 12th century Lewis chessmen. The top row shows king, queen, and bishop. The bottom row shows knight, rook, and pawn. The history of chess spans some 1500 years. The earliest predecessor of the game probably originated in India, before the 6th century AD. From India, the game spread to Persia. When the Arabs conquered Persia, chess was taken up by the Muslim world and subsequently spread to Southern Europe. In Europe, chess evolved into roughly its current form in the 15th century. The "Romantic Era of Chess" was the predominant chess playing style down to the 1880s. It was characterized by swashbuckling attacks, clever combinations, brash piece sacrifices and dynamic games. Winning was secondary to winning with style. These games were focused more on artistic expression, rather than technical mastery or long-term planning. The Romantic era of play was followed by the Scientific, Hypermodern, and New Dynamism eras.[1] In the second half of the 19th century, modern chess tournament play began, and the first World Chess Championship was held in 1886. The 20th century saw great leaps forward in chess theory and the establishment of the World Chess Federation (FIDE). Developments in the 21st century include use ofcomputers for analysis, which originated in the 1970s with the first programmed chess games on the market. Online gaming appeared in the mid-1990s. Contents [hide] 1 Origin 2 India -

FIDE Trainers Committee V22.1.2005

FIDE Training! Don’t miss the action! by International Master Jovan Petronic Chairman, FIDE Computer & Internet Chess Committee In 1998 FIDE formed a powerful Committee comprising of leading chess trainers around the chess globe. Accordingly, it was named the FIDE Trainers Committee, and below, I will try to summarize the immense useful information for the readers, current major chess training activities and appeals of the Committee, etc. Among their main tasks in the period 1998-2002 were FIDE licensing of chess trainers and the recognition of these by the International Olympic Committee, benefiting in the long run, to all chess federations, trainers and their students. The proven benefits of playing and studying chess have led to countries, such as Slovenia, introducing chess into their compulsory school curiccullum! The ASEAN Chess Academy, headed by FIDE Vice President, FM, IA & IO - Ignatius Leong, has organized from November 7th to 14th 2003 - a Training Course under the auspices of FIDE and the International Olympic Committee! IM Nikola Karaklajic from Serbia & Montenegro provided the training. The syllabus was targeted for middle and lower levels. At the time, the ASEAN Chess Academy had a syllabus for 200 lessons of 90 minutes each! I am personally proud of having completed such a Course in Singapore. You may view the official Certificate I received here. Another Trainers’ Course was conducted by FIDE and the Asean Chess Academy from 12th to 17th December 2004! Extensive testing was done, here is the list of the candidates who had passed the FIDE Trainer high criteria! The main lecturer was FIDE Senior Trainer Israel Gelfer.