The Streaking Star Effect: Why People Want Runs of Dominance by Individuals to Continue More Than Identical Runs by Groups

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019 Roland Garros Day 3 Men's Notes

2019 ROLAND GARROS DAY 3 MEN’S NOTES Tuesday 28 May 1st Round Featured matches No. 5 Alexander Zverev (GER) v John Millman (AUS) No. 8 Juan Martin del Potro (ARG) v Nicolas Jarry (CHI) No. 9 Fabio Fognini (ITA) v Andreas Seppi (ITA) No. 10 Karen Khachanov (RUS) v Cedrik-Marcel Stebe (GER) No. 14 Gael Monfils (FRA) v Taro Daniel (JPN) No. 18 Roberto Bautista Agut (ESP) v Steve Johnson (USA) No. 22 Lucas Pouille (FRA) v (Q) Simone Bolelli (ITA) (Q) Stefano Travaglia (ITA) v Adrian Mannarino (FRA) On court today… • France’s top 2 players begin their Roland Garros campaigns today, with Gael Monfils up against Taro Daniel on Court Philippe Chatrier and Lucas Pouille playing Simone Bolelli on Court Suzanne Lenglen. Both will aim to use home advantage to have a good run here this year – Monfils will look for a repeat of his 2008 performance when he reached the semifinals, while Pouille will hope to emulate the form he displayed in reaching the last 4 at the Australian Open in January to impress the home fans in Paris. • Monte Carlo champion Fabio Fognini takes on fellow Italian Andreas Seppi in the first match on Court Simonne Mathieu today. It will be the 8th all-Italian meeting at Roland Garros in the Open Era and the 16th all-Italian clash at the Grand Slams in the Open Era. The pair are tied at 4 wins apiece in their previous Tour-level match-ups, but Seppi has not beaten his compatriot and Davis Cup teammate since 2010 and will have to put in an inspired performance if he is to defeat to the No. -

Doubles Final (Seed)

2016 ATP TOURNAMENT & GRAND SLAM FINALS START DAY TOURNAMENT SINGLES FINAL (SEED) DOUBLES FINAL (SEED) 4-Jan Brisbane International presented by Suncorp (H) Brisbane $404780 4 Milos Raonic d. 2 Roger Federer 6-4 6-4 2 Kontinen-Peers d. WC Duckworth-Guccione 7-6 (4) 6-1 4-Jan Aircel Chennai Open (H) Chennai $425535 1 Stan Wawrinka d. 8 Borna Coric 6-3 7-5 3 Marach-F Martin d. Krajicek-Paire 6-3 7-5 4-Jan Qatar ExxonMobil Open (H) Doha $1189605 1 Novak Djokovic d. 1 Rafael Nadal 6-1 6-2 3 Lopez-Lopez d. 4 Petzschner-Peya 6-4 6-3 11-Jan ASB Classic (H) Auckland $463520 8 Roberto Bautista Agut d. Jack Sock 6-1 1-0 RET Pavic-Venus d. 4 Butorac-Lipsky 7-5 6-4 11-Jan Apia International Sydney (H) Sydney $404780 3 Viktor Troicki d. 4 Grigor Dimitrov 2-6 6-1 7-6 (7) J Murray-Soares d. 4 Bopanna-Mergea 6-3 7-6 (6) 18-Jan Australian Open (H) Melbourne A$19703000 1 Novak Djokovic d. 2 Andy Murray 6-1 7-5 7-6 (3) 7 J Murray-Soares d. Nestor-Stepanek 2-6 6-4 7-5 1-Feb Open Sud de France (IH) Montpellier €463520 1 Richard Gasquet d. 3 Paul-Henri Mathieu 7-5 6-4 2 Pavic-Venus d. WC Zverev-Zverev 7-5 7-6 (4) 1-Feb Ecuador Open Quito (C) Quito $463520 5 Victor Estrella Burgos d. 2 Thomaz Bellucci 4-6 7-6 (5) 6-2 Carreño Busta-Duran d. -

Signpost 11, Autumn 2019

Issue no. 11 Autumn 2019 1 Contents Page Correspondence 3 People on the move in Chipping Campden and District, 1200-1525 Christopher Dyer 9 A Scandal – Or A Love Story? Judith Ellis and Jennifer Bruce 16 From Mantua Maker to Oxford University Beadle: George Ballard (1706-1755), the Famous Antiquary of Chipping Campden Christopher Fance 20 CCHS Committee news 24 From the Editor We had such a lot of interesting correspondence to report in this issue, that it was quite lucky there was less Committee news. We are grateful to our President, Christopher Dyer, for sharing his researches after his last year’s talk to us about population movements in the middle ages. Christopher Fance’s article about George Ballard’s interests and academic skill shows what an amazing young man he was with little formal education. Judith Ellis and Jenny Bruce’s findings following the receipt of some Griffith’s family archive papers, as previously reported, is a fascinating story – indeed a scandal. My sincere thanks once again go to all correspondents, researchers and contributors – please, keep your articles coming - they are valuable and valued. Signpost is published by Chipping Campden History Society. © 2019 ISSN 2056-8924 Editor: Carol Jackson The Old Police Station, High Street, Chipping Campden, Gloucestershire, GL55 6HB. Tel: 01386-848840 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.chippingcampdenhistory.org.uk CCHS is committed to recognizing the intellectual property rights of others. We have therefore taken all reasonable efforts to ensure that the reproduction of the content on these pages is done with the full consent of copyright owners. -

Fifty Years in the Northwest: a Machine-Readable Transcription

Library of Congress Fifty years in the Northwest L34 3292 1 W. H. C. Folsom FIFTY YEARS IN THE NORTHWEST. WITH AN INTRODUCTION AND APPENDIX CONTAINING REMINISCENCES, INCIDENTS AND NOTES. BY W illiam . H enry . C arman . FOLSOM. EDITED BY E. E. EDWARDS. PUBLISHED BY PIONEER PRESS COMPANY. 1888. G.1694 F606 .F67 TO THE OLD SETTLERS OF WISCONSIN AND MINNESOTA, WHO, AS PIONEERS, AMIDST PRIVATIONS AND TOIL NOT KNOWN TO THOSE OF LATER GENERATION, LAID HERE THE FOUNDATIONS OF TWO GREAT STATES, AND HAVE LIVED TO SEE THE RESULT OF THEIR ARDUOUS LABORS IN THE TRANSFORMATION OF THE WILDERNESS—DURING FIFTY YEARS—INTO A FRUITFUL COUNTRY, IN THE BUILDING OF GREAT CITIES, IN THE ESTABLISHING OF ARTS AND MANUFACTURES, IN THE CREATION OF COMMERCE AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF AGRICULTURE, THIS WORK IS RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED BY THE AUTHOR, W. H. C. FOLSOM. PREFACE. Fifty years in the Northwest http://www.loc.gov/resource/lhbum.01070 Library of Congress At the age of nineteen years, I landed on the banks of the Upper Mississippi, pitching my tent at Prairie du Chien, then (1836) a military post known as Fort Crawford. I kept memoranda of my various changes, and many of the events transpiring. Subsequently, not, however, with any intention of publishing them in book form until 1876, when, reflecting that fifty years spent amidst the early and first white settlements, and continuing till the period of civilization and prosperity, itemized by an observer and participant in the stirring scenes and incidents depicted, might furnish material for an interesting volume, valuable to those who should come after me, I concluded to gather up the items and compile them in a convenient form. -

International Study Abroad and Exchange

Study in the heart in Sydney Study of International Study Abroad and Exchange Photo: Destination NSW Contents 02 Why UTS? Connect with us 03 Study in the heart of Sydney Welcome UTSInternationalstudents 04 Sydney’s city university UTSstudyabroad #UTSstudyabroad I’m pleased to introduce you to UTS’s Study Abroad and Exchange programs. Our 06 Campus and facilities programs offer you a unique opportunity to experience everything UTS has to UTSint #UTSint offer in one or two teaching sessions. 08 Living in UTS Housing UTS’s vision is to be a leading public university of technology recognised for 09 UTS rankings our global impact. We’re pleased to see that the excellence we strive towards is Acknowledgement 10 Your program options recognised worldwide. We’re ranked first in Australia and eleventh globally in the of Country world’s top 50 young universities (QS Top 50 Under 50 2020), and in the top 150 12 Study areas at UTS universities worldwide (QS World University Rankings 2020). “UTS’s vision is 24 Choosing your subjects Acknowledging country is a cultural protocol As a young university, we dare to think differently. We believe that you’ll need to that is a respectful public acknowledgment of to be a leading be adaptive and open-minded to succeed in our rapidly changing world – and 25 Credit, classes and assessment the traditional custodians of the land. we’ll prepare you for that. Our dynamic campus of the future, with its tech- 26 Services and support public university driven, collaborative spaces, will inspire you to learn, while our teaching style UTS acknowledges the Gadigal People of the places you at the centre of learning. -

Cheshire County Lta Junior Handbook 2020-2021 Cheshire County Lta Junior Handbook 2020-2021

CHESHIRE COUNTY LTA JUNIOR HANDBOOK 2020-2021 CHESHIRE COUNTY LTA JUNIOR HANDBOOK 2020-2021 CONTENTS Page Introduction - Chairman of Competitions & Tournaments Committee 1 County Junior Performance Coordinator 2 Annual Junior County Championships 3 County Championships Frequently Asked Questions 3 Fair Play 4 The Dick Fontes Cup 5 LTA Performance Strategy 2018-2028 5 Cheshire County LTA Junior County Championships 2019 6 Junior County Teams 8 LTA Rating and Age Group System 8 County Training Camps 9 County Training Programme 2020-21 10 Junior County Cup Results 2020 11 Junior Cheshire Shield 2019 12 National League 2020-21 13 LTA Youth 14 FAST4 TENNIS 14 Cheshire Insights 15 Alfie King 15 Rhona Cook 16 Hannah McColgan 17 Stuart Murray 19 Cheshire County Contact Details 21 CHESHIRE TENNIS JUNIOR COUNTY HANDBOOK INTRODUCTION Cheshire LTA’s Competition & Tournaments and Junior Performance Committees produce this handbook for the benefit of all Cheshire tennis clubs, as well as targeting junior players and their parents. Under normal circumstances we like to give news about some of our junior tennis players as well as the various age group County teams. As tennis at all levels has been severely disrupted since March, the contents of this year’s handbook will be different in that we have very few results to include but hopefully the changes we have made will prove both interesting and informative. We thought it would be a change to ask some of our junior county players to write about their tennis experiences so we asked Rhona Cook (18U Cheshire Junior Champion) to give an insight into what it was like playing in the 18U Junior County Cup event (played in February). -

Davis Cup-Bilanz Lorenzo Manta

Nation Activity Switzerland Since 2019 (New format) Davis Cup (World Group PO) PER d. SUI 3:1 in PER Club Lawn Tennis de la Exposición, Lima, Peru March 6 – March 7 2020 Clay (O) R1 Sandro EHRAT (SUII) L Juan Pablo VARILLAS (PER) 6-/(4) 6:7(3) R2 Henri LAAKSONEN (SUI) W Nicolas ALVAREZ (PER) 6:4, 6:4 R3 Sandro EHRAT/Luca MARGAROLI (SUI) L Sergio GALDOS / Jorge Brian PANTA (PER) 5:7, 6:7(8) R4 Henri LAAKSONEN (SUI) L Juan Pablo VARILLAS (PER) 3-6 6:3 6:7(3) R5 Not played Period W/L: 1 – 9 // 396 – 444 Davis Cup (World Group I PO) SVK d. SUI 3:1 in SVK AXA Arena, Bratislava, SVK September 13 – September 14 2019 Clay (O) R1 Sandro EHRAT (SUII) W Martin KLIZAN (SVK) 6-2 7-6(7) R2 Henri LAAKSONEN (SUI) L Andrej MARTIN (SVK) 2-6 6-4 5-7 R3 Henri LAAKSONEN / Jérôme KYM (SUI) L Evgeny DONSKOY / Andrey RUBLEV (SVK) 3-6 3-6 R4 Henri LAAKSONEN (SUI) L Norbert GOMBOS (SVK) 1-6 1-6 R5 Not played Period W/L: 2 – 6 // 395 – 441 Davis Cup (Qualifiers) RUS d. SUI 3:1 in SUI Qualifier 16 Swiss Tennis Arena, Biel-Bienne, SUI February 1 – February 2 2019 Hard (I) R1 Henri LAAKSONEN (SUI) L Daniil MEDVEDEV (RUS) 6-7(8) 7-6(6) 2-6 R2 Marc-Andrea HÜSLER (SUI) L Karen KHACHANOV (RUS) 3-6 5-7 R3 Henri LAAKSONEN / Jérôme KYM (SUI) W Evgeny DONSKOY / Andrey RUBLEV (RUS) 4-6 6-3 7-6(7) R4 Henri LAAKSONEN (SUI) L Karen KHACHANOV (RUS) 7-6(2) 6-7(6) 4-6 R5 Not played Period W/L: 1 – 3 // 394 – 438 1923 – 2018 Davis Cup (WG Playoffs) SWE d. -

Numbers Game the First Night Game at Yankee Stadium

This Day In Sports 1946 — The Washington Senators beat New York 2-1 in Numbers Game the first night game at Yankee Stadium. C4 Antelope Valley Press, Tuesday, May 28, 2019 Morning rush NBA Finals to decide champ, more Valley Press news services that player movement.’ On the By TIM REYNOLDS FREE AGENT Soto leads U.S. over Nigeria at Associated Press other hand, that player move- Under-20 World Cup It all comes down to this. Warriors guard ment could be very positive for a Sebastian Soto scored a pair of goals, and No, really. Klay Thompson lot of teams.” the United States beat Nigeria 2-0 Monday in the It ALL comes down to this. (11) celebrates Maybe, maybe not. Under-20 World Cup at Bielsko Biala, Poland, to The next four, five, six or sev- with fans after If the Warriors win this se- rebound from an opening loss to Ukraine. en games of the NBA Finals be- scoring against ries, as the oddsmakers in Las Soto headed in Alex Mendez’s corner kick tween Golden State and Toronto the Portland Trail Vegas expect, it’ll be a third con- from 5 yards in the 18th minute, getting free will not only decide the 2019 Blazers in Game secutive championship for Gold- from defender Zulkifilu Rabu, then doubled the championship, but how this se- 2 of the Western en State — and some history. lead 25 seconds into the second half. Left back The Celtics, Lakers and Bulls Chris Gloster, a teammate in Hannover’s youth ries plays out is inevitably going Conference finals system, dribbled toward goal from midfield and to affect how free agency unfolds in Oakland on May are the only franchises to win passed as Soto burst past defender Valentine starting in a month or so. -

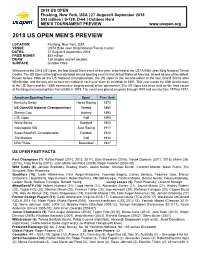

2018 Us Open Men's Preview

2018 US OPEN Flushing, New York, USA | 27 August-9 September 2018 $53 million | S-128, D-64 | Outdoor Hard MEN’S TOURNAMENT PREVIEW www.usopen.org 2018 US OPEN MEN’S PREVIEW LOCATION: Flushing, New York, USA VENUE: USTA Billie Jean King National Tennis Center DATES: 27 August-9 September 2018 PRIZE MONEY: $53 million DRAW: 128 singles and 64 doubles SURFACE: Outdoor Hard Welcome to the 2018 US Open, the last Grand Slam event of the year, to be held at the USTA Billie Jean King National Tennis Center. The US Open is the highest-attended annual sporting event in the United States of America, as well as one of the oldest. Known before 1968 as the US National Championships, the US Open is the second-oldest of the four Grand Slams after Wimbledon, and the only one to have been played each year since its inception in 1881. This year marks the 50th Anniversary of the US Open and the 138th consecutive staging overall of the tournament. The US Open has been held on the hard courts of Flushing since moving from Forest Hills in 1978. The event was played on grass through 1974 and on clay from 1975 to 1977. American Sporting Event Sport First Held Kentucky Derby Horse Racing 1875 US Open/US National Championships Tennis 1881 Stanley Cup Hockey 1893 U.S. Open Golf 1895 World Series Baseball 1903 Indianapolis 500 Auto Racing 1911 Super Bowl/NFL Championship Football 1920 The Masters Golf 1934 NBA Finals Basketball 1947 US OPEN FAST FACTS Past Champions (7): Rafael Nadal (2010, 2013, 2017), Stan Wawrinka (2016), Novak Djokovic (2011, 2015), Marin Cilic -

Novak Djokovic: 11 Títulos Con Andrey Kuznetsov)

Tenis internacional Líderes en títulos de Grand Slam 1º Roger Federer: 17 títulos Los títulos del tenista serbio Los 28 títulos Masters 1000 de Djokovic 2º Pete Sampras: 14 títulos Redacción Central y Agencias de un golpe de calor, se retiró cuando perdía 6 Miami 2007, 2008, 2011, 2014, 2015 y 2016.016. 3º Rafael Nadal: 14 títulos Hace tiempo que Roger Federer y Rafael Nadal con Damir Dzumhur, en la segunda rueda) y 2016 4 títulos 2011 10 títulos 5 Indian Wells 2008, 2011, 2014, 2015 y 2016. 4º Roy Emerson: 12 títulos Novak ya no replican su inigualable enfrentamiento a Stan Wawrinka (cayó en la segunda rueda ATP World Tour Masters 1000 Miami (Aire Libre/Hard) US Open (Aire Libre/Hard) 4 Roma 2008, 2011, 2014 y 2015. 5º Rod Laver, Björn Borg y Novak Djokovic: 11 títulos con Andrey Kuznetsov). Djokovic, pese a en las grandes deniciones del circuito ATP World Tour Masters 1000 Indian Wells (Aire Libre/Hard) ATP World Tour Masters 1000 Canada (Aire Libre/Hard) 4 Paris-Bercy 2009, 2013, 2014 y 2015. 6º Bill Tilden: 10 títulos algunos dolores de espalda y a cierta fatiga tenístico. El suizo no gana un Grand Slam Australian Open (Aire Libre/Hard) Wimbledon (Aire Libre/Grass) 3 Canadá 2007, 2011 y 2012. 7º Andre Agassi, Jimmy Connors, Ivan Lendl, Fred Perry y Ken Rosewall: 8 títulos Djokovic corporal, continuó de pie. Siempre de pie. Doha (Aire Libre/Hard) desde Wimbledon 2012, el español no lo hace ATP World Tour Masters 1000 Rome (Aire Libre/Clay) 3 Shanghai 2012, 2013 y 2105. -

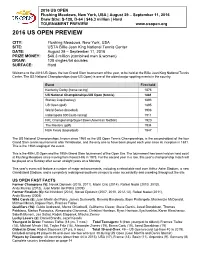

2016 Us Open Preview

2016 US OPEN Flushing Meadows, New York, USA | August 29 – September 11, 2016 Draw Size: S-128, D-64 | $46.3 million | Hard TOURNAMENT PREVIEW www.usopen.org 2016 US OPEN PREVIEW CITY: Flushing Meadows, New York, USA SITE: USTA Billie Jean King National Tennis Center DATE: August 29 – September 11, 2016 PRIZE MONEY: $46.3 million (combined men & women) DRAW: 128 singles/64 doubles SURFACE: Hard Welcome to the 2016 US Open, the last Grand Slam tournament of the year, to be held at the Billie Jean King National Tennis Center. The US National Championships (now US Open) is one of the oldest major sporting events in the country: Event First held Kentucky Derby (horse racing) 1875 US National Championships/US Open (tennis) 1881 Stanley Cup (hockey) 1893 US Open (golf) 1895 World Series (baseball) 1903 Indianapolis 500 (auto racing) 1911 NFL Championship/Super Bowl (American football) 1920 The Masters (golf) 1934 NBA Finals (basketball) 1947 The US National Championships, known since 1968 as the US Open Tennis Championships, is the second-oldest of the four Grand Slam tennis tournaments after Wimbledon, and the only one to have been played each year since its inception in 1881. This is the 136th staging of the event. This is the 49th US Open and the 195th Grand Slam tournament of the Open Era. The tournament has been held on hard court at Flushing Meadows since moving from Forest Hills in 1978. For the second year in a row, this year’s championship match will be played on a Sunday after seven straight years on a Monday. -

Missouri State University Spring 2020 Graduates (Sorted by Hometown)

Missouri State University Spring 2020 Graduates (Sorted by Hometown) 00-Unknown County City: Brandon Scott Berry: Bachelor of Science, Risk Management and Insurance Constance Ruth Brown: Master of Social Work Pierce Jovan Bryant: Bachelor of Science, Information Technology Reagan L. Caldwell: Master of Science, Communication Sciences and Disorders Trevor A. Calfee: Bachelor of General Studies Samantha Nicole Carton: Master of Science, Applied Behavior Analysis Hannah Elizabeth Casertano: Bachelor of Science in Education, Early Childhood Education , Cum Laude Chelsea Nicole Clothier: Bachelor of Science, Criminology Kathryn Lynn Couch: Bachelor of Science in Education, Elementary Education , Cum Laude Anthony Joseph Darnell: Bachelor of Science, General Business Olivia Leigh DeFay: Master of Arts in Teaching and Learning Desiree M. Ellis: Master of Business Administration Carlos Alfredo Garcia, Jr.: Master of Science, Counseling Joshua Kenneth Gibson: Bachelor of Science, Animal Science Thai Duong Q. Ha: Bachelor of Science, Cell and Molecular Biology Thomas Daniel Hardwicke: Doctor of Nurse Anesthesia Practice Savannah R. Hartje: Bachelor of Arts, English Abbigail Nancy Hartman: Bachelor of Science, Health Services Cameron David Hayter: Doctor of Nurse Anesthesia Practice Kaitlyn M. Herter: Bachelor of Science, Entrepreneurship Ethen Byron Highley: Bachelor of Science, General Business Jason David Ivanov: Bachelor of Science, Computer Information Systems Jesse James Jannink: Bachelor of Science, Digital Film and Television Production