Specific Human Capital As a Source of Superior Team Performance**

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

United in Solidarity. No Matter What

United in solidarity. No matter what. Sustainability Report for the 2019/2020 season " All generations, men and women, and all nationalities are united by Borussia." BORUSSIA DORTMUND GMBH & CO. KGAA Environmental responsibility AT A GLANCE 302-1 302-3 Energy used per 2019/2020 table Total energy Athletic development stadium seat 2019 BVB disclosure consumption Played W D L GF/GA Diff. Pts. in 2019 1. FC Bayern Munich 34 26 4 4 100:32 +68 82 kWh 2. Borussia Dortmund 34 21 6 7 84:41 +43 69 250 3. RB Leipzig 34 18 12 4 81:37 +44 66 20.4 GWh 4. Borussia M‘Gladbach 34 20 5 9 66:40 +26 65 306-3 305-4 5. Bayer 04 Leverkusen 34 19 6 9 61:44 +17 63 Total waste generated (excl. food waste) in 2019 6. TSG 1899 Hoffenheim 34 15 7 12 53:53 0 52 GHG emissions per 7. VfL Wolfsburg 34 13 10 11 48:46 +2 49 stadium seat 535 tonnes 8. SC Freiburg 34 13 9 12 48:47 +1 48 306-4 9. Eintracht Frankfurt 34 13 6 15 59:60 -1 45 41.6 kg CO2 Food waste in 2019 10. Hertha BSC 34 11 8 15 48:59 -11 41 11. 1. FC Union Berlin 34 12 5 17 41:58 -17 41 202.4 m³ 12. FC Schalke 04 34 9 12 13 38:58 -20 39 13. 1. FSV Mainz 05 34 11 4 19 44:65 -21 37 14. 1. FC Köln 34 10 6 18 51:69 -18 36 15. -

Sample Download

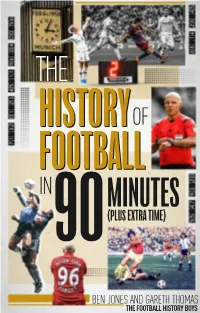

THE HISTORYHISTORYOF FOOTBALLFOOTBALL IN MINUTES 90 (PLUS EXTRA TIME) BEN JONES AND GARETH THOMAS THE FOOTBALL HISTORY BOYS Contents Introduction . 12 1 . Nándor Hidegkuti opens the scoring at Wembley (1953) 17 2 . Dennis Viollet puts Manchester United ahead in Belgrade (1958) . 20 3 . Gaztelu help brings Basque back to life (1976) . 22 4 . Wayne Rooney scores early against Iceland (2016) . 24. 5 . Brian Deane scores the Premier League’s first goal (1992) 27 6 . The FA Cup semi-final is abandoned at Hillsborough (1989) . 30. 7 . Cristiano Ronaldo completes a full 90 (2014) . 33. 8 . Christine Sinclair opens her international account (2000) . 35 . 9 . Play is stopped in Nantes to pay tribute to Emiliano Sala (2019) . 38. 10 . Xavi sets in motion one of football’s greatest team performances (2010) . 40. 11 . Roger Hunt begins the goal-rush on Match of the Day (1964) . 42. 12 . Ted Drake makes it 3-0 to England at the Battle of Highbury (1934) . 45 13 . Trevor Brooking wins it for the underdogs (1980) . 48 14 . Alfredo Di Stéfano scores for Real Madrid in the first European Cup Final (1956) . 50. 15 . The first FA Cup Final goal (1872) . 52 . 16 . Carli Lloyd completes a World Cup Final hat-trick from the halfway line (2015) . 55 17 . The first goal scored in the Champions League (1992) . 57 . 18 . Helmut Rahn equalises for West Germany in the Miracle of Bern (1954) . 60 19 . Lucien Laurent scores the first World Cup goal (1930) . 63 . 20 . Michelle Akers opens the scoring in the first Women’s World Cup Final (1991) . -

PH8 044-049 Meier (Page 44

EXKLUSIVSPORT MICHAEL MEIER – GESCHÄFTSFÜHRER VON BORUSSIA DORTMUND – IM GESPRÄCH „Real kann noch zehn Ronaldos kaufen“ Ruhig, besonnen und clever: Im großen PENTHOUSE-Interview spricht Michael Meier über seine Karriere und die wirtschaftliche Situation im Fußball. Interview: Jürgen Ponath, Fotos: Daniel Kölsche PENTHOUSE: Ihre Tätigkeit bei Vereinen der Ersten Bundesliga führte Sie vom 1. FC Köln über Bayer 04 Leverkusen zu Borussia Dort- mund. Was unterscheidet die Klubs voneinander? MICHAEL MEIER: Das kann man nicht in einem Satz beantworten. In Köln ist der Fußball sehr wichtig, in Leverkusen nur ein Teil dessen, was angeboten wird. Und in Dortmund ist der Fußball Hauptsache. Traditionsreich sind aber alle drei Vereine. Sicher. Die Unterschiede beginnen schon bei der Geburt. Der 1. FC Köln ist erst 1948 aus einer Fusion entstanden. Bayer Leverkusen wurde 1904 als Werks- verein gegründet. Schon deshalb sind die Vereine nicht vergleichbar. Borussia Dortmund hat eine Tradition als Arbeiterverein. Die Erfolgsgeschichte beweist die Ausnahmestellung des Vereins. 1966 gewann der BVB als erste deutsche Mann- schaft den Europapokal, 1997 die Champions League. Auf dem internationalen Parkett waren Köln und Leverkusen nicht so erfolgreich. Leverkusen wurde 1988 UEFA-Pokalsieger. Das habe ich dort selbst miterlebt. Es blieb der einzige ganz große Tag. Der 1. FC Köln konnte international nie durchschlagende Erfolge feiern. Was aber die wenigsten von den Kölnern wis- sen: Bis zum UEFA-Pokalfinale zwischen dem BVB und Juventus Turin (Anm. der Redaktion: Juventus bezwang 1993 den BVB mit 3:0 und 3:1 und wurde UEFA-Cup-Sieger) hatten sie die meisten Spiele in Europa absolviert. Mit dem Finale wurden sie von Juve abgelöst. -

Passion and Drive: Improving Together. Sustainability Report for the 2018/2019 Season "Real Love Is Not a Tagline but a Bond."

Passion and drive: Improving together. Sustainability Report for the 2018/2019 season "Real love is not a tagline but a bond." Carsten Cramer BORUSSIA DORTMUND GMBH & CO. KGAA Environmental responsibility AT A GLANCE Total energy Energy used Athletic development 2018/2019 table consumption per stadium seat BVB disclosure in 2018 Played W D L GF/GA Diff. Pts. in 2018 1. FC Bayern München 34 24 6 4 88:32 +56 78 kWh 2. Borussia Dortmund 34 23 7 4 81:44 +37 76 256 3. RB Leipzig 34 19 9 6 63:29 +34 66 20.8 GWh 4. Bayer 04 Leverkusen 34 18 4 12 69:52 +17 58 5. Borussia M‘Gladbach 34 16 7 11 55:42 +13 55 Total waste generated (excl. food waste) in 2018 6. VfL Wolfsburg 34 16 7 11 62:50 +12 55 GHG emissions per stadium seat 7. Eintracht Frankfurt 34 15 9 10 60:48 +12 54 498 tonnes 8. Werder Bremen 34 14 11 9 58:49 +9 53 9. TSG 1899 Hoffenheim 34 13 12 9 70:52 +18 51 45.0 kg CO2 Food waste in 2018 10. Fortuna Düsseldorf 34 13 5 16 49:65 -16 44 11. Herta BSC 34 11 10 13 49:57 -8 43 12. 1. FSV Mainz 05 34 12 7 15 46:57 -11 43 172.0 m³ 13. SC Freiburg 34 8 12 14 46:61 -15 36 14. FC Schalke 04 34 8 9 17 37:55 -18 33 15. FC Augsburg 34 8 8 18 51:71 -20 32 Social responsibility 16. -

German Bundesliga 1 1995-96

BORUSSIA DORTMUND Bundesliga 1 1995-96 Home Attack 2.65 Home Defence 0.82 Away Attack 1.82 Away Defence 1.41 Goalkeeper STEFAN KLOS (97) WOLFGANG DE BEER (99) HARALD SCHUMACHER (100) Penalty Taker STEFAN REUTER (60) ANDREAS MOLLER(80) MICHAEL ZORC (100) MICHAEL ZORC 20 RUBEN SOSA 87 HEIKO HERRLICH 30 STEFFEN FREUND 90 ANDREAS MOLLER 40 JORG HEINRICH 93 KARLHEINZ RIEDLE 50 JULIO CESAR 96 LARS RICKEN 58 RENE TRETSCHOK 99 JURGEN KOHLER 65 CARSTEN WOLTERS 100 PATRIK BERGER 71 STEPHANE CHAPUISAT 75 STEFAN REUTER 79 MATTHIAS SAMMER 83 FC BAYERN MUNCHEN Bundesliga 1 1995-96 Home Attack 2.06 Home Defence 1.18 Away Attack 1.82 Away Defence 1.53 Goalkeeper OLIVER KAHN (94) MICHAEL PROBST(97) SVEN SCHEUR (100) Penalty Taker MEHMET SCHOLL (50) JURGEN KLINSMANN (100) JURGEN KLINSMANN 22 ANDREAS HERZOG 90 ALEXANDER ZICKLER 35 JEAN-PIERRE PAPIN 93 MEHMET SCHOLL 47 CIRIOCO SFORZA 96 EMIL KOSTADINOV 55 OLIVER KREUZER 98 THOMAS HELMER 62 LOTHAR MATTHAUS 100 CHRISTIAN NERLINGER 69 THOMAS STRUNZ 76 CHRISTIAN ZIEGE 81 MARKUS BABBEL 84 DIETMAR HAMANN 87 FC SCHALKE 04 Bundesliga 1 1995-96 Home Attack 1.65 Home Defence 0.94 Away Attack 1.00 Away Defence 1.18 Goalkeeper JENS LEHMANN (94) JORG ALBRECHT (100) Penalty Taker INGO ANDERBRUGGE MARTIN MAX 28 ANDREAS MULLER 98 YOURI MULDER 53 UWE WEIDEMANN 100 INGO ANDERBRUGGE 66 THOMAS LINKE 73 OLAF THON 80 MICHAEL BUSKENS 85 DAVID WAGNER 90 TOM DOOLEY 92 WALDEMAR KSIENZYK 94 RADOSLAV LATAL 96 BORUSSIA MONCHENGLADBACH Bundesliga 1 1995-96 Home Attack 1.71 Home Defence 1.29 Away Attack 1.35 Away Defence 1.71 Goalkeeper -

BORUSSIA DORTMUND Bundesliga 1 1996-97

BORUSSIA DORTMUND Bundesliga 1 1996-97 Home Attack 2.24 Home Defence 0.76 Away Attack 1.47 Away Defence 1.65 Goalkeeper STEFAN KLOS Penalty Taker MICHAEL ZORC (60) STEPHANE CHAPUISAT (100) STEPHANE CHAPUISAT 18 IBRAHIM TANKO 88 HEIKO HERRLICH 31 VLADIMIR BUT 90 KARLHEINZ RIEDLE 43 JOVAN KIROVSKI 92 ANDREAS MOLLER 52 PAUL LAMBERT 94 JORG HEINRICH 59 PAULO SOUSA 96 MICHAEL ZORC 66 KNUT REINHARDT 98 JULIO CESAR 71 STEFAN REUTER 100 RENE TRETSCHOK 76 JURGEN KOHLER 80 LARS RICKEN 84 FC BAYERN MUNCHEN Bundesliga 1 1996-97 Home Attack 2.18 Home Defence 0.71 Away Attack 1.82 Away Defence 1.29 Goalkeeper OLIVER KAHN (94) SVEN SCHEUR (100) Penalty Taker MARIO BASLER JURGEN KLINSMANN 23 DIETMAR HAMANN 94 RUGGIERO RIZZITELLI 33 CARSTEN JANCKER 96 ALEXANDER ZICKLER 43 LOTHAR MATTHAUS 98 CHRISTIAN ZIEGE 53 THOMAS STRUNZ 100 MARIO BASLER 62 CHRISTIAN NERLINGER 70 MEHMET SCHOLL 78 THOMAS HELMER 84 MARCEL WITECZEK 89 MARKUS BABBEL 92 FC SCHALKE 04 Bundesliga 1 1996-97 Home Attack 1.12 Home Defence 0.82 Away Attack 0.94 Away Defence 1.53 Goalkeeper JENS LEHMANN Penalty Taker INGO ANDERBRUGGE MARTIN MAX 37 OLIVER HELD 100 MARC WILMOTS 55 YOURI MULDER 64 INGO ANDERBRUGGE 70 TOM DOOLEY 76 RADOSLAV LATAL 82 OLAF THON 88 MICHAEL BUSKENS 91 JOHAN DE KOCK 94 YVES EIGENRAUCH 97 BORUSSIA MONCHENGLADBACH Bundesliga 1 1996-97 Home Attack 2.00 Home Defence 1.00 Away Attack 0.71 Away Defence 1.82 Goalkeeper UWE KAMPS Penalty Taker IOAN LUPESCU MARTIN DAHLIN 25 IOAN LUPESCU 94 ANDRZEJ JUSKOWIAK 45 PETER NIELSEN 96 JORGEN PETTERSSON 63 STEPHAN PASSLACK 98 MARCO VILLA -

The DFB-Ligapokal 1997 (GER)

The DFB Super Cup 1987 - 1996 (FRG - GER) - The DFB-Ligapokal 1997 - 2004 (GER) - The Premiere-Ligapokal 2005 - 2007 (GER) - The DFL Super Cup 2010 - 2021 (GER) - The Match Details: The DFB Super Cup 1987 (FRG): 28.7.1987, Frankfurt am Main (FRG) - Waldstadion. FC Bayern München (FRG) - Hamburger SV (FRG) 2:1 (0:1). FC Bayern: Raimond Aumann - Norbert Nachtweih - Helmut Winklhofer, Norbert Eder, Johannes Christian 'Hansi' Pflügler - Andreas Brehme (46. Hans-Dieter Flick), Lothar Herbert Matthäus, Hans Dorfner, Michael Rummenigge - Roland Wohlfarth, Jürgen Wegmann - Coach: Josef 'Jupp' Heynckes. Hamburg: Ulrich 'Uli' Stein (Red Card - 87.) - Ditmar Jakobs - Manfred Kaltz, Dietmar Beiersdorfer, Thomas Hinz (90. Frank Schmöller) - Sascha Jusufi, Thomas von Heesen, Carsten Kober (88. Richard Golz), Thomas Kroth - Mirosław Okoński, Manfred Kastl - Coach: Josip Skoblar. Goals: 0:1 Mirosław Okoński (39.), 1:1 Jürgen Wegmann (60.) and 2:1 Jürgen Wegmann (87.). Referee: Dieter Pauly (FRG). Attendance: 18.000. The DFB Super Cup 1988 (FRG): 20.7.1988, Frankfurt am Main (FRG) - Waldstadion. SG Eintracht Frankfurt (FRG) - SV Werder Bremen (FRG) 0:2 (0:1). SG Eintracht: Ulrich 'Uli' Stein - Manfred Binz - Ralf Sievers, Karl-Heinz Körbel, Stefan Studer - Frank Schulz - Peter Hobday (46. Dietmar Roth), Dieter Schlindwein, Maximilian Heidenreich (57. Ralf Balzis) - Jørn Andersen, Heinz Gründel - Coach: Karl-Heinz Feldkamp. SV Werder: Oliver Reck - Gunnar Sauer - Ulrich 'Uli' Borowka, Michael Kutzop, Johnny Otten (46. Norbert Meier) - Thomas Schaaf, Miroslav 'Mirko' Votava, Günter Hermann, Frank Neubarth - Karlheinz Riedle, Frank Ordenewitz (46. Manfred Burgsmüller) - Coach: Otto Rehhagel. Goals: 0:1 Karlheinz Riedle (24.) and 0:2 Manfred Burgsmüller (90.). -

'Team Effectiveness in Organizational Contexts'

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2010 Team effectiveness in organizational contexts Pieper, Jan Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-164150 Dissertation Published Version Originally published at: Pieper, Jan. Team effectiveness in organizational contexts. 2010, University of Zurich, Faculty ofEco- nomics. TEAM EFFECTIVENESS IN ORGANIZATIONAL CONTEXTS Dissertation for the Faculty of Economics, Business Administration and Information Technology of the University of Zurich to achieve the title of Doctor of Philosophy in Management and Economics presented by Jan Pieper from Germany approved in October 2010 at the request of Prof. Dr. Egon Franck and Prof. Dr. Helmut Dietl II The Faculty of Economics, Business Administration and Information Technology of the University of Zurich hereby authorises the printing of this Doctoral Thesis, wit- hout thereby giving any opinion on the views contained therein. Zurich, October 27th, 2010 Chairman of the Doctoral Committee: Prof. Dr. Dieter Pfaff III Preface No one is able to produce a great work without experience, nor fill an influential posi- tion immediately. In the interval between initial failure and subsequent success, in the gap between who we wish to be one day and who we are at present, conflicts and set- backs are hardly avoidable. The tempting belief that achievement must come easily or not at all needs to be corrected because it is ruinous in its effect. It can lead to prema- ture withdrawal from challenging, but worthwhile and realizable objectives. -

Funke: Sammer Wird BVB-Berater – Kehl Oder Ricken

Funke: Sammer wird BVB- Berater – Kehl oder Ricken Sportlicher Leiter dpa/Sven Hoppe Dortmund (dpa) – Erst war Matthias Sammer der Kopf beim größten Erfolg der Vereinsgeschichte, dann wurden er und die Bosse von Borussia Dortmund erbitterte Rivalen, nun kommt es nach 14 Jahren offenbar zur Wiedervereinigung: Der Meistertrainer soll nach Informationen der Funke Mediengruppe als externer Berater zum Fußball-Bundesligisten zurückkehren. Der BVB bestätigte der Deutschen Presse-Agentur entsprechende Gespräche. Ebenfalls bestätigte der Verein die Einführung des Postens eines Leiters Lizenzspielerabteilung unter der Führung von Sportdirektor Michael Zorc. Dieser soll nach Funke- Informationen entweder Sebastian Kehl oder Lars Ricken werden – auch diese beiden haben eine lange und erfolgreiche Vergangenheit als BVB-Spieler. «Wir benötigen einen wie Matthias Sammer. Seine Analyse- Fähigkeit, seine Leidenschaft, seine Identifikation, seinen klaren Blick von außen», sagte Watzke. Er habe sich deshalb «seit geraumer Zeit» um ihn bemüht. Die Meinungsverschiedenheiten aus Sammers Zeit als Sportvorstand beim Erzrivalen FC Bayern seien längst ausgeräumt, versicherte Watzke. «Seine Rolle bei Bayern war dominanter, als wir das hier wahrgenommen haben», sagte der Geschäftsführer: «Ich habe von mehreren Spielern gehört, welche Bedeutung Matthias für das Mannschaftsgefüge hatte. Als seine Bayern-Zeit zu Ende ging, wir älter und reifer und vernünftiger wurden, haben wir uns sukzessive angenähert. Ich habe schnell gemerkt, dass Matthias eine viel höhere BVB-Affinität hat als viele glauben.» Ins Tagesgeschäft soll Sammer, der aktuell als Experte beim TV-Sender Eurosport arbeitet, sich nicht einschalten, er solle seine Einschätzungen als Berater abgeben. «Unser Anspruch ist: Alles kritisch auf den Prüfstand zu stellen», sagte Watzke. Er verspricht sich «frischen Wind und hohe Kompetenz» sowie «eine unbequeme, aber von Vertrauen geprägte Diskussionskultur». -

K262 Description.Indd

AGON SportsWorld 1 65 th Auction Descriptions AGON SportsWorld 2 65 th Auction 65 th AGON Sportsmemorabilia Auction 23rd and 24th June 2017 Contents 23 rd and 24th June 2017 Lots 1 - 1514 Olympics 6 Olympic Autographs 65 Other Sports 69 Football World Cup 80 German match worn shirts 120 Football in general 133 German Football 134 International Football 152 International match worn shirts 158 Football Autographs 182 The essentials in a few words: Bidsheet extra sheet - all prices are estimates - they do not include value-added tax; 7% VAT will be additionally charged with the invoice. - if you cannot attend the public auction, you may send us a written order for your bidding. - in case of written bids the award occurs in an optimal way. For example:estimate price for the lot is 100,- €. You bid 120,- €. a) you are the only bidder. You obtain the lot for 100,-€. b) Someone else bids 100,- €. You obtain the lot for 110,- €. c) Someone else bids 130,- €. You lose. - In special cases and according to an agreement with the auctioneer you may bid by telephone during the auction. (English and French telephone service is availab- le). - The price called out ie. your bid is the award price without fee and VAT. - The auction fee amounts to 15%. - The total price is composed as follows: award price + 15% fee = subtotal + 7% VAT = total price. - The items can be paid and taken immediately after the auction. Successful orders by phone or letter will be delivered by mail (if no other arrange- ment has been made). -

Sagenhafter Bvb 11 2. Kapitel: Rote Erde, Gelbe Wand

1. KAPITEL: SPIELE, SPIELER, TRIUMPHE: SAGENHAFTER BVB 11 Weil Andreas Möller keine Ahnung von Geografie hat und deshalb wohl auf Schalke gelandet sein muss - Weil Schalker in Dortmund manchmal doch zum Anbeißen sind - Weil Dortmund Emmerich und Held, Chapuisat und Riedle hatte - Weil Gott meinte, er müsse für die Niederkunft auf Erden Fußballschuhe schnüren und sich die Gestalt von Jürgen Kohler aussuchen - Weil Kohler teuflischerweise in seinem letzten Profispiel mit einer roten Karte verabschiedet wurde - Weil Matthias Sammer mit klaffender Platzwunde spielte - Weil Dortmund beim unfairsten Ligaspiel noch nicht einmal die unfairste Mannschaft war - Weil Jens Lehmann in Dortmund immer Köpfchen bewies - Weil Lars Ricken das schönste, tollste, unfassbarste Jokertor überhaupt geschossen hat - Weil man in Dortmund keine 76 Minuten braucht, um ein Tor aufzustellen - Weil Dortmund immer an Dede geglaubt hat - Weil Frank Mill ein Pfosten ist - Weil Dortmunds erfolgreichster Torschütze sogar das Zeug zum Football-Profi hatte - Weil man in Dortmund nur drei Spiele braucht, um nicht abzusteigen - Weil Nor bert Dickel im Knieumdrehen das Pokalfinale gewonnen hat - Weil das Management im Verein die Michaels machen, nur bitte niemals der Preetz 2. KAPITEL: ROTE ERDE, GELBE WAND: DAS STADION UND DIE FANS ... 49 Weil die Stimmung im Westfalenstadion einmalig, sagenumwoben, ja ge radezu magisch ist ~ Weil allein die Südtribüne größer ist als das gesamte Stadion des SC Freiburg, der BVB aber weiß, dass im Breisgau echtes Format steckt - Weil der Signal -

Duit-Players-Lit.Pdf

BOOKS: - 1. FC Lokomotive Leipzig (Hrsg.): 1987. Der Triumphzug des 1. FC Lok Leipzig durch Europa, Leipzig 2017. - AGON: Deutscher Meister 1995/96 Borussia Dortmund, Kassel 1996. - Altendorfer, Otto: Die Fußball-Nationaltrainer der DDR zwischen SED und Staatssicherheit. Eine biografische Dokumentation, Leipzig 2014. - Autorenkollektiv vom Sportverlag Berlin: Fußball-Weltmeisterschaft Chile 1962, Berlin 1962. - Baingo, Andreas (Hrsg.): England '96. Der totale Fußball-EM-Planer, Leck 1996. - Baingo, Andreas/Heidrich, Herbert/Nachtigall, Rainer: Dynamo Dresden. Ein Fußballklub stellt sich vor, Berlin 1987. - Baingo, Andreas/Hohlfeld, Michael/Riemann, Matthias: Oberliga Nordost - 1000 Tage 3. Liga, Berlin 1994. - Baingo, Andreas/Hohlfeld, Michael/Radunz, Harry (Redaktion): Zauberwelt Fußball. Stars - Rekorde - Sensationen, Berlin 1999. - Baingo, Andreas/Hohlfeld, Michael: Fussball-Auswahlspieler der DDR. Das Lexikon, Berlin 2000. - Baingo, Andreas/Horn, Michael: Bundesliga '98/'99. Der Fuballsaisonplaner, Berlin 1998. - Baingo, Andreas/Horn, Michael: Die Geschichte der DDR-Oberliga, Göttingen 2003. - Bauer, Gerd: Richtig Fußballspielen, München 1990. - Bauman, Rainer/Friedemann, Horst/Hempel, Wolf/Schlegel, Klaus/Simon, Günter: Im Banne des Balls, Berlin 1965. - Bechtermünz Verlag: Illustriertes Regel-Lexikon des Sports, Augsburg 1996. - Beckenbauer, Franz (Hrsg.): Fußball Weltmeisterschaft, München 1998. - Bedürftig, Friedemann: Mexico 86. XIII. Fußball-Weltmeisterschaft, München/Zürich 1986. - Bender, Tom/Kühne-Hellmessen, Ulrich: Verrückte