Epilogue to the Devils of Loudun Aldous Huxley Without An

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DVD Press Release

DVD press release The Devils 2-Disc Special Edition A film by Ken Russell Vanessa Redgrave, Oliver Reed Forty years ago, The Devils caused outrage amongst audiences and critics after one of the longest-running battles with the BBFC was resolved and the film finally opened in cinemas. Now recognised as a landmark in British film history, The Devils finally gets its DVD premiere on 19 March, released by the BFI in the original UK X certificate version with a wealth of new and exciting extra features and a 44-page illustrated booklet. The death of director Ken Russell, in November last year, sparked an outpouring of tributes from both the film industry and fans. This 2-disc Special Edition release of what many consider to be his greatest work is a justly fitting tribute to one of Britain’s true mavericks. The Devils is based on John Whiting’s stage play and Aldous Huxley’s novel. In 17th century France, a promiscuous and divisive local priest, Urbain Grandier (Oliver Reed), uses his powers to protect the city of Loudun from destruction by the establishment. Soon, he stands accused of the demonic possession of Sister Jeanne (Vanessa Redgrave), whose erotic obsession with him fuels the hysterical fervour that sweeps through the convent. With Ken Russell’s bold and brilliant direction, magnificent performances by Oliver Reed and Vanessa Redgrave, exquisite Derek Jarman sets and a sublimely dissonant score by Sir Peter Maxwell Davies, The Devils stands as a profound and sincere commentary on religious hysteria, political persecution and the corrupt marriage of church and state. -

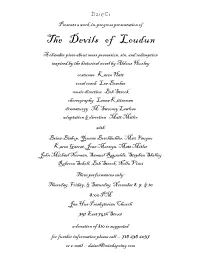

The Devils of Loudun

DzieCi Presents a work-in-progress presentation of The Devils of Loudun A chamber piece about mass possession, sin, and redemption inspired by the historical novel by Aldous Huxley costumes Karen Hatt vocal coach Lea Bracher music direction Bob Strock choreography Lenna Kitterman dramaturgy M. Sweeney Lawless adaptation & direction Matt Mitler with Brina Bishop, Yvonne Brechbuhler, Max Faugno Karen Garrat, Joan Merwyn, Matt Mitler John Michael Norman, Samuel Reynolds, Stephen Shelley Rebecca Sokoll, Bob Strock, Nella Vinci Three performances only: Thursday, Friday, & Saturday, November 8, 9, & 10 8:00 PM Jan Hus Presbyterian Church 351 East 74th Street a donation of $10 is suggested for further information please call -- 718 638 6037 or e-mail -- [email protected] Long is the way and hard, that out of Hell leads up to Light. Milton, Paradise Lost A Note on the Production The international experimental theatre company, DZIECI, has been working diligently but quietly. For almost five years now, an intense effort has been made to train each member and develop a tightly knit ensemble while exploring an organic process toward creativity and personal growth. Towards this aim, DZIECI balances its work on performance with work of service through creative and therapeutic interactions with patients in a variety of institutional settings. Since its inception, DZIECI has been involved in an open-ended process of adapting and rehearsing Aldous Huxley's historical treatise, The Devils of Loudun. The story centers around a group of 17th century Ursuline nuns who, inspired by their Prioress, Sister Jeanne des Anges, became officially "possessed" and were forced to undergo public exorcisms. -

Rethinking Jeanne and the Theme of the Supernatural

RETHINKING JEANNE AND THE THEME OF THE SUPERNATURAL IN DIE TEUFEL VON LOUDUN by JINKYUNG LEE (Under the Direction of David Haas) ABSTRACT Krzysztof Penderecki’s (b. 1933) Die Teufel von Loudun is an adaptation of a play by John Whiting that tells a story of demonic possession and exorcism based on a historical event in Loudun. Previous scholars have neglected the supernatural element, despite the clear evidence that Penderecki changed texts and reordered the plot to make Jeanne’s supernatural experiences more convincing and more significant to the plot. Through strange shifts in vocal range and timbre, evocative orchestration, and unusual uses of the chorus, Penderecki revealed the coexistence of two realms: one natural and one supernatural. At times, he blurred the border between the realms through ambiguous musical effects involving oddly mismatched timbres. Elsewhere he made structural links between scenes in order to reveal previously hidden supernatural elements. Penderecki’s multiple evocations of the supernatural through music add an important dimension to the opera and make the character Jeanne central to understanding it. INDEX WORDS: Krysztof Penderecki, Die Teufel von Loudun, Jeanne, Demonic Possession, Exorcism, Supernatural RETHINKING JEANNE AND THE THEME OF THE SUPERNATURAL IN DIE TEUFEL VON LOUDUN by JINKYUNG LEE B.M., Seoul National University, Republic of Korea, 2006 M.M., Seoul National University, Republic of Korea, 2010 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2017 © 2017 JinKyung Lee All Rights Reserved RETHINKING JEANNE AND THE THEME OF THE SUPERNATURAL IN DIE TEUFEL VON LOUDUN by JINKYUNG LEE Major Professor: David Hass Committee: Dorothea Link Rebecca Simpson-Litke Electronic Version Approved: Suzanne Barbour Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia August 2017 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My deep gratitude goes first to my advisor, Dr. -

The Loudun Possessions: Witchcraft Trials at the Jacob Burns Law Library

LH&RB Newsletter of the Legal History & Rare Books Special Interest Section of the American Association of Law Libraries Volume 16 Number 3 Hallowe’en 2010 The Loudun Possessions: Witchcraft Trials at The Jacob Burns Law Library by Mary Kate Hunter* Harry Potter. Sabrina, The Teenage Witch. Bewitched. Are there really any “evil” witches anymore? Popular culture has turned once-feared hags and sorcerers into “cool” phenomena. Now it seems we ponder witchcraft mainly for entertainment, during Hallowe’en, or in an election year when a political candidate reveals a youthful dabbling in the satanic.1 But four hundred years ago, witches were serious business. The possessions began September 22, 1632, in the west-central French town of Loudun, in a climate of uncertainty. A serious concern which occupied the collective thoughts of many French communities at the time, including Loudun, was the Crown’s attempt to centralize its power by tearing down city walls. The royal order for demolition divided Loudun along the lines of those who wanted to keep the walls – generally, the Huguenots – and those who sided with the Crown and its desire for a strong central government – in large part, the Catholic population. Compounding the distress generated by this political wrestling was a return of the plague to Loudun in May, 1632, which claimed the lives of a significant segment of the Loudun population. These circumstances fueled apprehension about the future, and created an atmosphere of anxiety which set the scene for one of the most notorious witchcraft trials in history. Urbain Grandier arrived in Loudun in 1617, having been granted two lucrative benefices by the Jesuits: the office of parish priest of Saint-Pierre-du-Marché, and appointment as a canon at the Church of Sainte-Croix. -

The Devils Rose Free

FREE THE DEVILS ROSE PDF Gerald Brom | 128 pages | 01 Oct 2007 | Abrams | 9780810993532 | English | New York, United States The Devils () - IMDb From " Veronica Mars " to Rebecca take a look back at the career of Armie Hammer on and off the screen. See the full gallery. Cardinal Richelieu and his power-hungry entourage seek The Devils Rose take control of seventeenth-century France, but need to destroy Father Grandier - the priest who runs the fortified town that prevents them from exerting total control. So they seek to destroy him by setting him up The Devils Rose a warlock in control The Devils Rose a devil-possessed nunnery, the mother superior of which is sexually obsessed by him. A mad witch-hunter is brought in to gather evidence against the priest, ready for the big trial. Written by Films Ranked. British director Ken Russell's adaption of Aldous Huxley's book "The Devils of Loudun" is one of the most origional, controversial and daring films ever made. The film takes place in 17th-century France and centres on the hypocritical and licentious behaviour of debauched priest Father Urbain Grandier, brilliantly played by Oliver Reed. The Devils Rose second plot strand involves the humpbacked nunn Sister Jeanne, played by Vanessa Redgrave, who, along with her fellow nuns, is obsessed with Grandier. When the nuns become seemingly possessed, disgruntled representatives of the Catholic Church and corrupt officials move in and seize their opportunity to get rid of Grandier. The film gets off to an excellent start, gradually building up the tension and highlighting the flaws within the Catholic religion. -

Edinburgh Research Explorer

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Edinburgh Research Explorer Edinburgh Research Explorer Mother Joan and Her Discontents: On Mother Joan of the Angels / Matka Joanna od Anioów (Jerzy Kawalerowicz, 1960) Citation for published version: Sorfa, D 2012, 'Mother Joan and Her Discontents: On Mother Joan of the Angels / Matka Joanna od Anioów (Jerzy Kawalerowicz, 1960)' Second Run Booklet, pp. 7-17. Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Early version, also known as pre-print Published In: Second Run Booklet General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 05. Apr. 2019 [This is the original submitted version before the final copyedit by the publisher. The version in print was shortened due to length constraints] Mother Joan and Her Discontents David Sorfa I wanted to make a film about human nature and its innate reaction against repression and laws which are imposed on it. (Jerzy Kawalerowicz) Mother Joan of the Angels (Matka Joanna od Aniołów, 1960) tells the story of the burgeoning love between a nun ostensibly possessed by a variety of demons and the exorcist, the last of many, who has come to deliver her from her torments. -

Dvd Press Release

BFI news release BFI to bring Ken Russell’s controversial masterpiece The Devils to DVD for the first time 15 November 2011 – The BFI is thrilled to announce that it will be releasing one of the ‘most-wanted’ British films of all time, Ken Russell’s bold and brilliant religious drama The Devils (1971), on DVD for the first time. Forty years ago, The Devils caused outrage amongst audiences and critics after one of the longest-running battles with the BBFC was resolved, and the film was finally seen in cinemas. Now recognised as a landmark in British cinema history the film will at long last get its DVD premiere on 19 March 2012, in the original UK ‘X’ certificate version. Oliver Reed and Vanessa Redgrave give magnificent performances in what remains Ken Russell’s most dazzling and controversial film – for which he won the prize for Best Director, Foreign Film at the Venice Film Festival. Based on John Whiting’s stage-play and Aldous Huxley’s novel, the film charts the seventeenth- century events that took place in the French city of Loudun. Reed plays priest Urbain Grandier, and Redgrave is Sister Jeanne, whose erotic obsession with him fuels the hysterical fervour that sweeps through the convent. Derek Jarman designed the striking, highly memorable sets and Sir Peter Maxwell Davies composed a supremely well-matched score for Russell’s arresting depiction of the breakdown of civilisation. Film critic and expert Mark Kermode, who has written and broadcast extensively about The Devils, will be contributing to the special features. He comments: ‘Ken Russell is one of Britain's greatest living filmmakers and The Devils remains his most incendiary work – an extraordinary and impassioned depiction of the unholy marriage of church and state which is as relevant today as it was when the film was first released.’ Sam Dunn, Head of BFI Video Publishing says: ‘We are absolutely delighted to be able to announce the DVD premiere release of this extraordinary film. -

WHIRLWINDS in the NARRATIVE of the DEVILS of LOUDUN, by ALDOUS HUXLEY: a STUDY on TRUTH, FICTION, JUSTICE 1 INTRODUCTION the T

ANAMORPHOSIS – Revista Internacional de Direito e Literatura v. 6, n. 1, janeiro-junho 2020 © 2020 by RDL – doi: 10.21119/anamps.61.37-60 WHIRLWINDS IN THE NARRATIVE OF THE DEVILS OF LOUDUN, BY ALDOUS HUXLEY: A STUDY ON TRUTH, FICTION, JUSTICE HILDA HELENA SOARES BENTES1 TRANSLATED BY FELIPE ZOBARAN ABSTRACT: This paper analyzes the “historical narrative” novel The Devils of Loudun, by Aldous Huxley, which tells the story of a supposed demonic possession case happened in a convent of Ursuline nuns in the beginning of the 17th century. It is about a real event that brings up a series of thoughts on the importance of the law, as well as the role of literature and philosophy, fiction, truth, justice and its relation with vengeance and revenge. The objective is to depart from the theory of law in order to study the literary work. Also, this paper aims at establishing to what extent the process of telling the truth can be twisted by revenge, as a primitive instinct of annihilating an enemy. It is a theoretical investigation, accomplished by bibliographic research, with an interdisciplinary approach between law and literature. Keywords: truth; verisimilitude; literature; justice; revenge. 1 INTRODUCTION The “historical narrative” novel The Devils of Loudun, by Aldous Huxley, tells the story of a supposed demonic possession case happened in a convent of Ursuline nuns in the beginning of the 17th century. It is about a real event that brings up a series of thoughts on legal philosophy. This paper analyzes the novel, with special emphasis on the concepts of truth, 1 Ph.D. -

Bob Wiseman's Ecomusicological Puppetry

Environmental Humanities, vol. 4, 2014, pp. 69-93 www.environmentalhumanities.org ISSN: 2201-1919 Refining Uranium: Bob Wiseman’s Ecomusicological Puppetry Andrew Mark Faculty of Environmental Studies, York University, Canada ABSTRACT This paper describes Bob Wiseman’s allegorical piece, Uranium, arguing that it accesses emotion to alter the consciousness of percipients. Audiences respond with unusual intensity to Uranium’s tragic environmental narrative. By using puppet theatre, film, comedy, and song to win their trust, Wiseman is able to shock his spectators. With interviews and consideration of the semiotic content of Uranium, I explore possibilities for activation of ecological consciousness through performing arts. Building on the shared ideas of Heinrich von Kleist, Gregory Bateson, and Thomas Turino, I argue that Wiseman offers one particularly useful mechanism to advance environmental concerns and learning through the arts. This paper seeks to bridge environmental and (ethno)musicological thought, and has specific relevance to the growing field of ecomusicology, presenting a musical ethnographic case-study in singer-song-writer activism. Introductions On a crisp evening that marked the start of Ontario’s autumn, Bob Wiseman performed under a full moon for some 2,000 people at the 2009 Shelter Valley Folk Festival. Facing a barn, bundled up in lawn chairs or on tarps, we were a receptive audience. Surrounded by shocked and weeping people, memories from the night haunt me. Wiseman, mid-set, brought the tragedy of nuclear mining home without shaming, tiring, or losing our attention. Later Wiseman told me, “my job would be a breeze if I only had to perform for family-friendly folk festivals.”1 What follows is a musical ethnographic2 retracing of the creation of Wiseman’s four and a half minute powerful, ecological, allegorical, and political piece, Uranium. -

Ken Russell Als Regisseur

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Tarek Krohn; Hans Jürgen Wulff Ken Russell als Regisseur. Chronologische Filmographie 2010 https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/12739 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Buch / book Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Krohn, Tarek; Wulff, Hans Jürgen: Ken Russell als Regisseur. Chronologische Filmographie. Hamburg: Universität Hamburg, Institut für Germanistik 2010 (Medienwissenschaft: Berichte und Papiere 110). DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/12739. Erstmalig hier erschienen / Initial publication here: https://doi.org/http://berichte.derwulff.de/0110_10.pdf Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Creative Commons - This document is made available under a creative commons - Namensnennung - Nicht kommerziell - Keine Bearbeitungen 4.0/ Attribution - Non Commercial - No Derivatives 4.0/ License. For Lizenz zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu dieser Lizenz more information see: finden Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Medienwissenschaft / Hamburg: Berichte und Papiere 110, 2010: Ken Russell. Redaktion und Copyright dieser Ausgabe: Tarek Krohn u. Hans J. Wulff. URL: http://www.rrz.uni-hamburg.de/Medien/berichte/arbeiten/0110_10.pdf. Letzte Änderung: 26.2.2012. Inhalt: Zum Tod Ken Russells / Julian Lucks Ken Russell als Regisseur: Chronologische Filmographie / komp. v. Tarek Krohn u. Hans J. Wulff Ken Russell – Bibliographie / komp. v. Hans J. Wulff in Zusammenarb. mit Tarek Krohn Julian Lux SAVAGE MESSIAH (1972) und MAHLER (1974), Histori- Zum Tod Ken Russells endramen wie der berüchtigte THE DEVILS (1971), Li- teraturverfilmungen (u.a. SALOMES LAST DANCE, 1988), Musicals wie die Rock-Oper TOMMY (1975) mit der britischen Band „The Who“, Milieustudien „Ken Russell ist tot“, so echot es seit dem 27. -

The History of the Devils of Loudun; the Alleged Possession of the Ursuline

;^ } I i , r l'< Boston Medical Library in the Francis A. Countway Library of Medicine -Boston THE DEVILS OF LOUDUN. [COLLECTANEA ADAMANT^EA.-XXL] THE HISTORY OF THE Bcvils of Xoubun, The Alleged Possession of the Ursuline Nuns^ and the Triat and Execution of Urbain Grandier, TOLD BY AN EYE-WITNESS. TRANSLATED FROM THE ORIGINAL FRENCH, AND EDMUND GOLDSMID, F.R.H.S., F.S.A. (Scot.) ^voinr PKIVATELY PRINTED. EDINBURGH. 1887. This Edition is limited to 275 small-paper and 75 larqe-paper copies. [Facsimile of Tifle-Page.'\ LA VERITABLE HISTOIRE DES y De la 'possession des Religieuscs Ursulines et de la Condamnation B'URBAIN GRJNDIER, Par UN TEMOIN. A. POITIERS, Thoreau et la Chez J. veuve Menier, Imprimeurs ordinaires du Roi et de rUniversitie. M. DC. XX XIV. Digitized by tine Internet Arciiive in 2010 witii funding from Open Knowledge Commons and Harvard Medical School http://www.archive.org/details/historyofdevilsoOOdesn 3(ntrotiuction. >§o€< ^fc^IIE following extraordinary account of the ^^ / 1 Cause Celebre" of Urbain Grandier, ^M^ the Cure of Loudun, accused of Magic and of having caused the Nuns of the Convent of Saint Ursula to be possessed of devils, is written by an eye-witness, and not only an eye- witness but an actor in the scenes he describes. It is printed at *' Poitiers, chez J, Thoreau et la veuve Menier, Imprimeurs du Roi et de V Univer- site^ 1634." I believe two copies only are known: my own, and the one in the National Library, Paris. The writer is Monsieur des Niau, Coun- sellor at la Fleche, evidently a firm believer in the absurd charges brought against Grandier.